Chondromalacia patellae

| Chondromalacia patella | |

|---|---|

| Other names: CMP | |

| |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

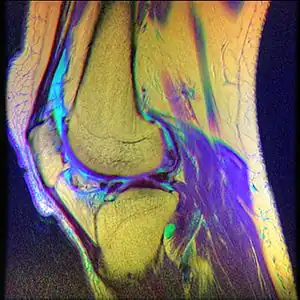

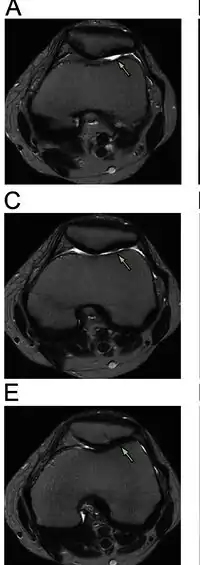

| Diagnostic method | MRI |

Chondromalacia patellae (also known as CMP) is an inflammation of the underside of the patella and softening of the cartilage.

The cartilage under the kneecap is a natural shock absorber, and overuse, injury, and many other factors can cause increased deterioration and breakdown of the cartilage. The cartilage is no longer smooth and therefore movement and use is very painful.[1] While it often affects young individuals engaged in active sports, it also afflicts older adults who overwork their knees.[2][3]

Chondromalacia patellae is sometimes used synonymously with patellofemoral pain syndrome.[4] However, there is general consensus that patellofemoral pain syndrome applies only to individuals without cartilage damage.[4][5] This condition is also known as Chondrosis.[6][7][8][9] The term literally translates to softening (malakia) of cartilage (chondros) behind patella in Greek. [10]

Signs and symptoms

The presentation of chondromalacia patellae is consistent with anterior knee pain and swelling[11]

Cause

The condition may result from acute injury to the patella or chronic friction between the patella and a groove in the femur through which it passes during knee flexion.[12] Possible causes include a tight iliotibial band, neuromas, bursitis, overuse, malalignment, core instability, and patellar maltracking.

Pain at the front or inner side of the knee is common in adults of all ages especially when engaging in soccer, gymnastics, cycling, rowing, tennis, ballet, basketball, horseback riding, volleyball, running, combat sports, figure skating, snowboarding, skateboarding and even swimming. The pain is typically felt after prolonged sitting.[13] Skateboarders most commonly experience this injury in their non-dominant foot due to the constant kicking and twisting required of it. Swimmers acquire it doing the breaststroke, which demands an unusual motion of the knee. People who are involved in an active lifestyle with high impact on the knees are at greatest risk. Proper management of physical activity may help prevent worsening of the condition. Athletes are advised to talk to a physician for further medical diagnosis, as symptoms may be similar to more serious problems within the knee. Tests are not necessarily needed for diagnosis, but in some situations they may confirm diagnosis or rule out other causes for pain. Commonly used tests are blood tests, MRI scans, and arthroscopy.[14]

While the term chondromalacia sometimes refers to abnormal-appearing cartilage anywhere in the body,[15] it most commonly denotes irritation of the underside of the kneecap (or "patella"). The patella's posterior surface is covered with a layer of smooth cartilage, which the base of the femur normally glides smoothly against when the knee is bent. However, in some individuals the kneecap tends to rub against one side of the knee joint, irritating the cartilage and causing knee pain.[16]

Diagnosis

When investigating a possible diagnosis of chondromalacia, a physician will carry out a complete examination of the affected knee. The physician will palpate the patella and surrounding tissue, feel the joint to observe when and how the distress manifests and obtains a list of symptoms and clinical history. The following tests or procedures may be used to refine the diagnosis:

- A knee X-ray and/or blood test – this can assist to exclude certain types of arthritis or inflammation.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) – to observe cartilage condition and assess deterioration

- Arthroscopy – a low invasive approach to image the inside of the knee joint by inserting an endoscope into the knee joint.[17]

Treatment

In the absence of cartilage damage, pain at the front of the knee due to overuse can be managed with a combination of RICE (rest, ice, compression, elevation), anti-inflammatory medications, and physiotherapy.[18]

Usually chondromalacia develops without swelling or bruising and most individuals benefit from rest and adherence to an appropriate physical therapy program. Allowing inflammation to subside while avoiding irritating activities for several weeks is followed by a gradual resumption. Cross-training activities such as swimming – using strokes other than the breaststroke – can help to maintain general fitness and body composition. This is beneficial until a physical therapy program emphasizing strengthening and flexibility of the hip and thigh muscles can be undertaken. Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication is also helpful to minimize the swelling amplifying patellar pain. Treatment with surgery is declining in popularity due to positive non-surgical outcomes and the relative ineffectiveness of surgical intervention.[16]

See also

References

- ↑ "Chondromalicia patella". Mayo Clinic. Mayo Foundation for Medial Education and Research (MFMER). Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ↑ Grelsamer, Ronald P (2005). "Patellar Nomenclature". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (436): 60–5. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000171545.38095.3e. PMID 15995421.

- ↑ "Isolated patellofemoral arthritis often overlooked". Academy News. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. February 6, 1999. Archived from the original on May 31, 2017. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- 1 2 Heintjes, E; Berger, MY; Bierma-Zeinstra, SM; Bernsen, RM; Verhaar, JA; Koes, BW (2004). "Pharmacotherapy for patellofemoral pain syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008 (3): CD003470. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003470.pub2. PMC 8276350. PMID 15266488.

- ↑ Dixit, S; DiFiori, JP; Burton, M; Mines, B (Jan 15, 2007). "Management of patellofemoral pain syndrome". American Family Physician. 75 (2): 194–202. PMID 17263214. Archived from the original on August 9, 2019. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ↑ "Disorders of the Patellofemoral Joint Chapter 11". www.patellofemoral.org. Archived from the original on 2021-07-14. Retrieved 2021-07-14.

- ↑ Skalski, Matt. "Chondromalacia grading | Radiology Case | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia. Archived from the original on 2021-07-14. Retrieved 2021-07-14.

- ↑ "Chondral Injuries - Causes, Symptoms, Treatment & Prevention". Orthosports Medical Center. Archived from the original on 2021-07-14. Retrieved 2021-07-14.

- ↑ "Treatment of Chondral (Cartilage) Lesions | Knee Arthroscopy | Knee Osteoarthritis Treatment". www.drkharrazi.com. Archived from the original on 2021-10-16. Retrieved 2021-07-14.

- ↑ "Chondromalacia Patellae". Physiopedia. Archived from the original on 2021-07-14. Retrieved 2021-07-14.

- ↑ Zheng, W; Li, H; Hu, K; Li, L; Bei, M (18 July 2021). "Chondromalacia patellae: current options and emerging cell therapies". Stem cell research & therapy. 12 (1): 412. doi:10.1186/s13287-021-02478-4. PMID 34275494. Archived from the original on 31 July 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ↑ Shiel, William C.; Cunha, John P. (June 27, 2012). "Chondromalacia Patella". MedicineNet. Archived from the original on June 29, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ↑ Gauresh. "Knee Cap Pain". Archived from the original on 2012-07-21. Retrieved 2022-10-01.

- ↑ "Chondromalacia patellae". Health Information Patient.info. Egton Medical Information Systems Ltd. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ↑ Schindler, Oliver S. (2004). "Synovial plicae of the knee". Current Orthopaedics. 18 (3): 210–9. doi:10.1016/j.cuor.2004.03.005.

- 1 2 Cluett, Jonathan (June 14, 2011). "Chondromalacia". About.com. Archived from the original on April 13, 2016. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ↑ "Knee Pain (Chondromalacia Patella): Causes, Symptoms & Treatment". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on 2021-04-11. Retrieved 2021-04-01.

- ↑ Jenkins, Mark A.; Caryn Honig (2005-06-02). "Patello-Femoral Syndrome". Archived from the original on 2008-10-09. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |