College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario

The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO) is the regulatory college for medical doctors in Ontario, Canada.

The college issues certificates of registration for all doctors to allow them to practise medicine as well as: monitors and maintains standards of practice via assessment and remediation, investigates complaints against doctors, and disciplines those found guilty of professional misconduct and/or incompetence.

The CPSO's power is derived from Regulated Health Professions Act (RHPA), Health Professions Procedural Code under RHPA and the Medicine Act. The college is based in Toronto.

Structure and mission

The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO) is the self-regulating body for the province's medical profession. The College regulates the practice of medicine to protect and serve the public interest. It issues certificates of registration to doctors to allow them to practise medicine, monitors and maintains standards of practice through peer assessment and remediation, investigates complaints against doctors on behalf of the public, and disciplines doctors who may have committed an act of professional misconduct or incompetence.[1]

The medical profession has been granted a great degree of authority by provincial law, and that authority is exercised through the College. This system of self-regulation is based on the premise that the College must act first and foremost in the interest of the public. All doctors in Ontario must be members of the College in order to practise medicine in the province. The role of the College, as well as its authority and powers, are set out in the Regulated Health Professions Act (RHPA), the Health Professions Procedural Code under the RHPA and the Medicine Act.

The duties of the College include: issuing certificates of registration to doctors to allow them to practise medicine monitoring and maintaining standards of practice through peer assessment and remediation investigating complaints about doctors on behalf of the public, and conducting discipline hearings when doctors may have committed an act of professional misconduct or incompetence.

The College is governed by a council. The RHPA stipulates that it consist of at least 32 and no more than 34 members: 16 physicians elected by their peers on a geographical basis every three years; 3 physicians appointed from among the six faculties of medicine (at the University of Western Ontario, McMaster University, University of Toronto, Queen's University, University of Ottawa, and the Northern Ontario School of Medicine); no fewer than 13 and no more than 15 non-physician or 'public' members appointed by the provincial government for terms decided by the government.

Both medical faculty members and public members may be re-appointed at the end of their terms. The College President is elected from and by Council and serves a one-year term.

Council members sit on one or more committees of the College. Each committee has specific functions, most of which are governed by provincial legislation.

General Council meetings are held four times a year, at which time the activities of the College are reviewed and matters of general policy are debated and voted on.

Meetings of Council are open to the public and are held in the 3rd floor Council Chamber at 80 College Street, Toronto, Ontario.

In October 2008, the College was named one of "Canada's Top 100 Employers" by Mediacorp Canada Inc., and was featured in Maclean's newsmagazine. Later that month, the College was also named one of Greater Toronto's Top Employers, which was announced by the Toronto Star newspaper.[2]

Complaints process

The complaints process regarding physicians begins with a phone call to the Public Advisory Department at 416-967-2603 or 1-800-268-7096, extension 603. A College staff member in the Investigations and Resolutions Department experienced in health care will help the caller. Staff may be able to answer questions about care, clarify which questions to take back to one's doctor, and/or answer questions about how the health care system works. The caller's medical records may be reviewed and a discussion with the doctor in question will be scheduled. Staff will ask the doctor for a response.

College staff may also arrange to meet with the individual who initiates the complaints process, and possibly with this individual and the doctor(s) – perhaps even hospital administrators – to communicate and clarify issues. This gives the individual who initiates the complaints process the opportunity to tell the doctor and others about any concerns.

This process provides a forum for individuals to have their concerns heard and acknowledged by the doctor and/or hospital representatives, and is done only with both the patient and the doctor's agreement. Occasionally, an improvement to the way in which health care is delivered has come about as a result of these discussions.

Criticisms associated with the college

Cautions

Between 2007 and 2013 the College issued more than 1,000 "cautions" against practising doctors.[3] Cautions are issued to doctors for transgressions that include providing inadequate treatment, poor record-keeping and raising voices in arguments. However, the college has been criticized in the past for not being transparent to patients as to which doctors have been subject to cautions. The college has been criticized for being more interested in protecting doctors than patients.

Block fees

Between 2004 and 2011 the College prosecuted four physicians for improperly charging block fees to patients. Block fees are annual fees charged by physicians to allow patients to access services. Physicians are permitted to charge block fees to uninsured patients for services not covered by OHIP, but charging block fees to allow insured patients to access OHIP services is considered to be professional misconduct.[4]

The "Transparency Project"

In 2013, in response to some of the above criticisms, the College announced that it would begin its "Transparency Project". The goal of the Transparency Project would be to make it easier for patients to gain more information about doctors who have been accused of wrongdoing. The College Council gave its support to a transparency initiative that had four categories. One, an increase in the transparency of the transfer of patient medical records. Two, a proposal that the Notices of Hearing for the College's Discipline Proceedings be posted to a physician's profile on the public register. Third, a proposal that the status of discipline matters as they are proceeding be added to a physician's profile on the public register. Fourth, that reinstatement decisions in their entirety be posted to a physician's profile on the public register.

Complaint disposal times

In recent years the College has struggled to process an increasing volume of complaints about physicians, probably because patients’ expectations are increasing rather than physicians getting worse. In 2007 it successfully lobbied the Ontario Ministry of Health to increase the time limit for disposal of complaints from 120 to 150 days, and to give itself increased powers to extend those time limits. These proposals were contained in amendments to the Regulated Health Professions Act 1991 which were passed by the Ontario Legislative Assembly in 2007 and came into force in 2009. The time taken to dispose of complaints continued to lengthen until the Ontario Ministry of Health commissioned a report, “Streamlining the Physician Complaints Process in Ontario” which reported in 2016 that “More time and money is spent on a disposition in Ontario than in other jurisdictions, with little apparent benefit to the public in terms of better or safer physician services”, “too many complaints and investigations are in the system too long”, and “the 150 day deadline is not met on many occasions”.[5] Following this report, the College improved the efficiency of its complaints procedures, including routing suitable complaints via an Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) process, and disposal times are once again coming down.

“Never reapply” undertakings

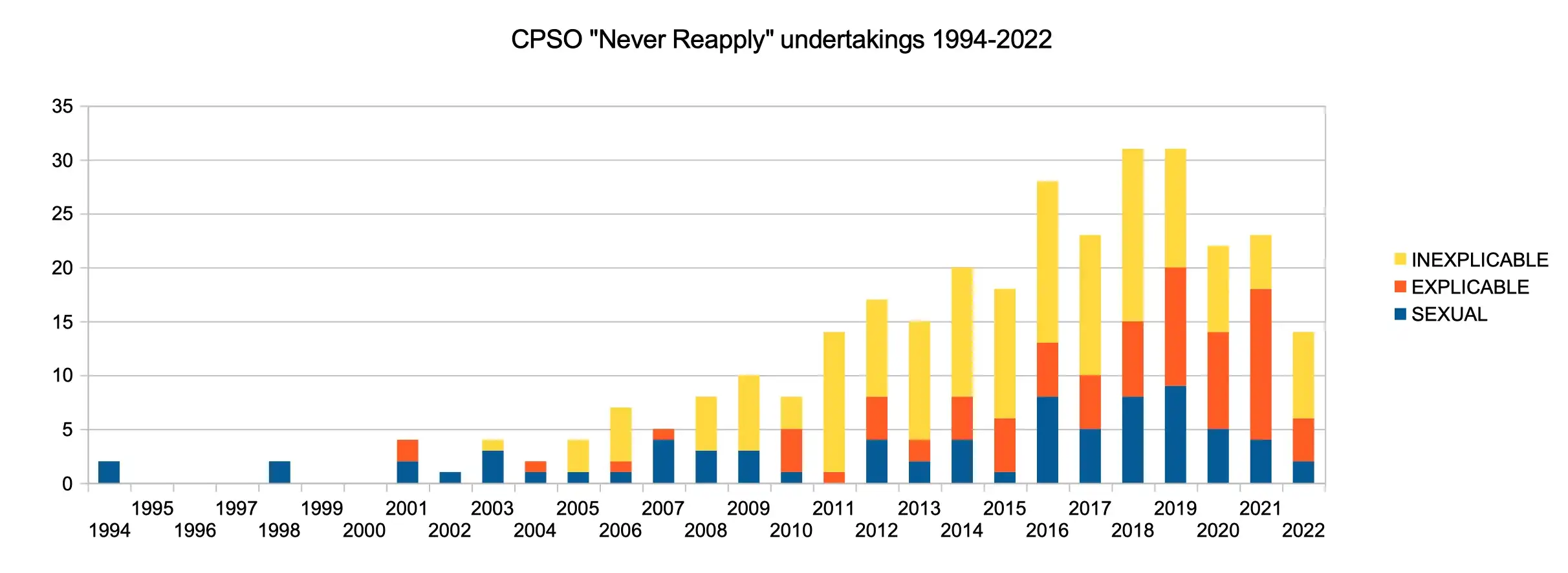

A novel solution adopted by the College to the problem of delays in resolving complaints has been to make increasing use of “never reapply” undertakings. A “never reapply” undertaking is an undertaking made by a physician to surrender his or her licence and never reapply for another licence in Ontario or anywhere else in the world. In return, the College promises not to proceed with the complaint, the investigation is terminated and the file closed. These undertakings are probably legally unenforceable both inside and outside Ontario as they would amount to an unreasonable restraint of trade [6] and they are rarely used by other medical regulatory authorities. In the past, such undertakings were only used in the most serious cases, for example sexual abuse of a patient, but they are increasingly being used by the College as a way of disposing of less serious or unspecified complaints. A disadvantage of these undertakings are that they remove physicians from practice who may be able and willing to continue practising but just wish to terminate the investigation. The following chart shows the College's use of “never reapply” undertakings from 1994 onwards.

This data was extracted from the CPSO online public register by a combination of electronic and manual searching. 285 physicians were identified who had given undertakings to the CPSO never to reapply for a licence either in Ontario alone, or Ontario plus anywhere else in the world.

In each case an attempt was made to identify why the undertaking was given, and the undertakings were allocated into three categories. “Sexual” indicates that there was an allegation of sexual misconduct, either proven or unproven, and involving either patients or co-workers. “Explicable” indicates that the reason for the undertaking was non-sexual, but there appeared to be some other good reason why it was appropriate, for example, gross incompetence, a serious criminal conviction, dishonesty, psychiatric incapacity or a repeated failure to remediate. “Inexplicable” forms the largest category and indicates either that the reason given was vague (”incompetence”, “professional misconduct”, “failure to uphold the standards of the profession” or similar) or that it appeared to be an inappropriately harsh penalty (over-prescribing of opioids, for example, could be easily remedied by placing restrictions on the physician’s licence).

Proposed amendments to the Regulated Health Professions Act 1991

An application is being made to the Ontario Ministry of Health for amendments to the Regulated Health Professions Act 1991 to update the regulations and address some of the above issues.[7]

See also

- Ontario Medical Association

- Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada

- Collège des médecins du Québec

References

- ↑ Armstrong, Laura (September 18, 2014). "Mississauga doctor sees male-only patients after sexual abuse discipline". Toronto Star. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Reasons for Selection, 2009 Canada's Top 100 Employers Competition".

- ↑ Boyle, Theresa (July 2, 2013). "College of Physicians and Surgeons wants more transparency about doctor discipline". Toronto Star. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Pediatrician fights CPSO over uninsured services" (PDF).

- ↑ Streamlining the Physician Complaints Process in Ontario. Stephen Goudge QC. 9 February 2016.

- ↑ Memorandum, “Non-Competition Agreements And Restraint Of Trade”. Daniel A. Nelson, 21 July 2009.

- ↑ Submission to Ontario Ministry of Health.

External links

- College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario - Official web site of the CPSO.