Compensatory growth (organ)

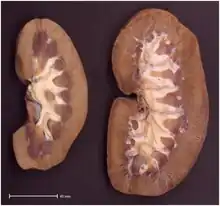

Compensatory growth is a type of regenerative growth that can take place in a number of human organs after the organs are either damaged, removed, or cease to function.[1] Additionally, increased functional demand can also stimulate this growth in tissues and organs.[2] The growth can be a result of increased cell size (compensatory hypertrophy) or an increase in cell division (compensatory hyperplasia) or both.[3] For instance, if one kidney is surgically removed, the cells of other kidney divide at an increased rate.[1] Eventually, the remaining kidney can grow until its mass approaches the combined mass of two kidneys.[1] Along with the kidneys, compensatory growth has also been characterized in a number of other tissues and organs including:

- the adrenal glands[4][5]

- the heart[5][6]

- muscles[5]

- the liver[5][7]

- the lungs[8]

- the pancreas (beta cells and acinar cells)[7]

- the mammary gland[5]

- the spleen (where bone marrow and lymphatic tissue undergo compensatory hypertrophy and assumes the spleen function during spleen injury)[5]

- the testicles[5]

- the thyroid gland[5][9]

- The turbinates

A large number of growth factors and hormones are involved with compensatory growth, but the exact mechanism is not fully understood and probably varies between different organs.[1] Nevertheless, angiogenic growth factors which control the growth of blood vessels are particularly important because blood flow significantly determines the maximum growth of an organ.[1]

Compensatory growth may also refer to the accelerated growth following a period of slowed growth, particularly as a result of nutrient deprivation.

See also

- Hyperplasia

- Hypertrophy

- Cellular adaptation

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Widmaier, E. P.; Raff, H. & Strang, K. T. (2006). Vander's Human Physiology: The Mechanisms Of Body Function (10th ed.). Boston, Mass: McGraw-Hill Companies. pp. 383. ISBN 978-0-07-282741-5.

- ↑ Goss, R. (1965). "Kinetics of Compensatory Growth". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 40 (2): 123–146. doi:10.1086/404538. PMID 14338253. S2CID 19069765.

- ↑ "compensatory growth (biology) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ↑ Swale Vincent (1912). Internal secretion and the ductless glands. Arnold. p. 150. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Francis Delafield; Theophil Mitchell Prudden (1907). A text-book of pathology with an introductory section on post-mortem examinations and the methods of preserving and examining diseased tissues. William Wood and Company. pp. 61–62. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ↑ M. I. Gabriel Khan (5 December 2005). Encyclopedia of heart diseases. Academic Press. pp. 493–494. ISBN 978-0-12-406061-6. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- 1 2 Anthony Atala (2008). Principles of regenerative medicine. Academic Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-0-12-369410-2. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ↑ Rannels, D. (1989). "Role of physical forces in compensatory growth of the lung". The American Journal of Physiology. 257 (4 Pt 1): L179–L189. doi:10.1152/ajplung.1989.257.4.L179. PMID 2679138.

- ↑ Harold Clarence Ernst (1919). The Journal of medical research. p. 199. Retrieved 10 June 2011.