Vermicompost

Vermicomposting=worm composting

Vermicompost (vermi-compost) is the product of the decomposition process using various species of worms, usually red wigglers, white worms, and other earthworms, to create a mixture of decomposing vegetable or food waste, bedding materials, and vermicast. This process is called vermicomposting, while the rearing of worms for this purpose is called vermiculture.

Vermicast (also called worm castings, worm humus, worm manure, or worm feces) is the end-product of the breakdown of organic matter by earthworms.[1] These castings have been shown to contain reduced levels of contaminants and a higher saturation of nutrients than the organic materials before vermicomposting.[2]

Vermicompost contains water-soluble nutrients and is an excellent, nutrient-rich organic fertilizer and soil conditioner.[3] It is used in gardening and sustainable, organic farming.

Vermicomposting can also be applied for treatment of sewage. A variation of the process is vermifiltration (or vermidigestion) which is used to remove organic matter, pathogens and oxygen demand from wastewater or directly from blackwater of flush toilets.[4][5]

Overview

Vermicomposting has gained popularity in both industrial and domestic settings because, as compared with conventional composting, it provides a way to treat organic wastes more quickly. In manure composting, it also generates products that have lower salinity levels.[6]

The earthworm species (or composting worms) most often used are red wigglers (Eisenia fetida or Eisenia andrei), though European nightcrawlers (Eisenia hortensis, synonym Dendrobaena veneta) and red earthworm (Lumbricus rubellus) could also be used.[7] Red wigglers are recommended by most vermicomposting experts, as they have some of the best appetites and breed very quickly. Users refer to European nightcrawlers by a variety of other names, including dendrobaenas, dendras, Dutch nightcrawlers, and Belgian nightcrawlers.

Containing water-soluble nutrients, vermicompost is a nutrient-rich organic fertilizer and soil conditioner in a form that is relatively easy for plants to absorb.[3] Worm castings are sometimes used as an organic fertilizer. Because the earthworms grind and uniformly mix minerals in simple forms, plants need only minimal effort to obtain them. The worms' digestive systems create environments that allow certain species of microbes to thrive to help create a "living" soil environment for plants.[8] The fraction of soil which has gone through the digestive tract of earthworms is called the drilosphere.[9]

Vermicomposting is a common practice in permaculture.[10][11]

Design considerations

Suitable worm species

All worms make compost but some species are not suitable for this purpose. Species most often used for composting include:

- Eisenia fetida, the red wiggler or tiger worm (Eisenia andrei)

- Lumbricus rubellus, does not adapt as well to the shallow compost bin as does Eisenia fetida

- Eisenia hortensis, European nightcrawlers, aka dendrobaenas, dendras, and nightcrawlers

- Eudrilus eugeniae, African Nightcrawlers

- Perionyx excavatus, Blueworms may be used in the tropics.[12]

These species commonly are found in organic-rich soils throughout Europe and North America and live in rotting vegetation, compost, and manure piles. They may be an invasive species in some areas.[1][13] As they are shallow-dwelling and feed on decomposing plant matter in the soil, they adapt easily to living on food or plant waste in the confines of a worm bin.

Composting worms are available to order online, from nursery mail-order suppliers or angling shops where they are sold as bait. They can also be collected from compost and manure piles. These species are not the same worms that are found in ordinary soil or on pavement when the soil is flooded by water.

Lumbricus terrestris (a.k.a. Canadian nightcrawlers (US) or common earthworm (UK)) are not recommended, since they burrow deeper than most compost bins can accommodate.[14]

Large scale

Large-scale vermicomposting is practiced in Canada, Italy, Japan, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, and the United States.[15] The vermicompost may be used for farming, landscaping, to create compost tea, or for sale. Some of these operations produce worms for bait and/or home vermicomposting.

There are two main methods of large-scale vermicomposting, windrow and raised bed. Some systems use a windrow, which consists of bedding materials for the earthworms to live in and acts as a large bin; organic material is added to it. Although the windrow has no physical barriers to prevent worms from escaping, in theory they should not, due to an abundance of organic matter for them to feed on. Often windrows are used on a concrete surface to prevent predators from gaining access to the worm population.

The windrow method and compost windrow turners were developed by Fletcher Sims Jr. of the Compost Corporation in Canyon, Texas. The Windrow Composting system is noted as a sustainable, cost-efficient way for farmers to manage dairy waste.[16]

The second type of large-scale vermicomposting system is the raised bed or flow-through system. Here the worms are fed an inch of "worm chow" across the top of the bed, and an inch of castings are harvested from below by pulling a breaker bar across the large mesh screen which forms the base of the bed.

Because red worms are surface dwellers constantly moving towards the new food source, the flow-through system eliminates the need to separate worms from the castings before packaging. Flow-through systems are well suited to indoor facilities, making them the preferred choice for operations in colder climates.

Small scale

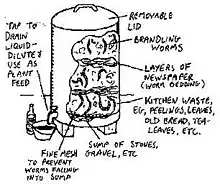

For vermicomposting at home, a large variety of bins are commercially available, or a variety of adapted containers may be used. They may be made of old plastic containers, wood, Styrofoam, or metal containers. The design of a small bin usually depends on where an individual wishes to store the bin and how they wish to feed the worms.

Some materials are less desirable than others in worm bin construction. Metal containers often conduct heat too readily, are prone to rusting, and may release heavy metals into the vermicompost. Styrofoam containers may release chemicals into the organic material.[17] Some cedars, yellow cedar, and redwood contain resinous oils that may harm worms,[18] although western red cedar has excellent longevity in composting conditions. Hemlock is another inexpensive and fairly rot-resistant wood species that may be used to build worm bins.[19]

Bins need holes or mesh for aeration. Some people add a spout or holes in the bottom for excess liquid to drain into a tray for collection.[20] The most common materials used are plastic: recycled polyethylene and polypropylene and wood.[21] Worm compost bins made from plastic are ideal, but require more drainage than wooden ones because they are non-absorbent. However, wooden bins will eventually decay and need to be replaced.

Small-scale vermicomposting is well-suited to turn kitchen waste into high-quality soil amendments, where space is limited. Worms can decompose organic matter without the additional human physical effort (turning the bin) that bin composting requires.

Composting worms which are detritivorous (eaters of trash), such as the red wiggler Eisenia fetida, are epigeic (surface dwellers) and together with symbiotic associated microbes are the ideal vectors for decomposing food waste. Common earthworms such as Lumbricus terrestris are anecic (deep burrowing) species and hence unsuitable for use in a closed system.[22] Other soil species that contribute include insects, other worms and molds.[23]

Climate and temperature

There may be differences in vermicomposting method depending on the climate.[24] It is necessary to monitor the temperatures of large-scale bin systems (which can have high heat-retentive properties), as the raw materials or feedstocks used can compost, heating up the worm bins as they decay and killing the worms.

The most common worms used in composting systems, redworms (Eisenia fetida, Eisenia andrei, and Lumbricus rubellus) feed most rapidly at temperatures of 15–25 °C (59-77 °F). They can survive at 10 °C (50 °F). Temperatures above 30 °C (86 °F) may harm them.[25] This temperature range means that indoor vermicomposting with redworms is possible in all but tropical climates. Other worms like Perionyx excavatus are suitable for warmer climates.[26] If a worm bin is kept outside, it should be placed in a sheltered position away from direct sunlight and insulated against frost in winter.

Feedstock

There are few food wastes that vermicomposting cannot compost, although meat waste and dairy products are likely to putrefy, and in outdoor bins can attract vermin. Green waste should be added in moderation to avoid heating the bin.

Small-scale or home systems

Such systems usually use kitchen and garden waste, using "earthworms and other microorganisms to digest organic wastes, such as kitchen scraps".[27] This includes:

- All fruits and vegetables (including citrus, in limited quantities)

- Vegetable and fruit peels and ends

- Coffee grounds and filters

- Tea bags (even those with high tannin levels)

- Grains such as bread, cracker and cereal (including moldy and stale)

- Eggshells (rinsed off)

- Leaves and grass clippings (not sprayed with pesticides[28])

- Newspapers (most inks used in newspapers are not toxic)

- Paper toweling (which has not been used with cleaners or chemicals)

Large-scale or commercial

Such vermicomposting systems need reliable sources of large quantities of food. Systems presently operating[29] use:

- Dairy cow or pig manure

- Sewage sludge[30][31]

- Brewery waste

- Cotton mill waste

- Agricultural waste

- Food processing and grocery waste

- Cafeteria waste

- Grass clippings and wood chips

Harvesting

Factors affecting the speed of composting include the climate and the method of composting. There are signs to look for to determine whether compost is finished. The finished compost would have an ambient temperature, dark color, and be as moist as a damp sponge. Towards the end of the process, bacteria slow down the rate of metabolizing food or stop completely. There is the possibility of some solid organic matter still being present in the compost at this point, but it could stay in and continue decomposing for the next couple of years unless removed. The compost should be allowed to cure after finished to allow acids to be removed over time so it becomes more neutral, which could take up to three months and results in the compost being more consistent in size. Elevating the maturing compost off the ground can prevent unwanted plant growth. It compost should consistently be slightly damp and should be aerated but doesn't need to be turned. The curing process can be done in a storage bin or on a tarp.[32]

Methods

Vermicompost is ready for harvest when it contains few-to-no scraps of uneaten food or bedding.[27] There are several methods of harvesting from small-scale systems: "dump and hand sort", "let the worms do the sorting", "alternate containers" and "divide and dump."[33] These differ on the amount of time and labor involved and whether the vermicomposter wants to save as many worms as possible from being trapped in the harvested compost.

The pyramid method of harvesting worm compost is commonly used in small-scale vermicomposting, and is considered the simplest method for single layer bins.[34] In this process, compost is separated into large clumps, which is placed back into composting for further breakdown, and lighter compost, with which the rest of the process continues. This lighter mix is placed into small piles on a tarp under the sunlight. The worms instinctively burrow to the bottom of the pile. After a few minutes, the top of the pyramid is removed repeatedly, until the worms are again visible. This repeats until the mound is composed mostly of worms.

When harvesting the compost, it is possible to separate eggs and cocoons and return them to the bin, thereby ensuring new worms are hatched. Cocoons are small, lemon-shaped yellowish objects that can usually be seen with the naked eye.[35] The cocoons can hold up to 20 worms (though 2-3 is most common). Cocoons can lay dormant for as long as two years if conditions are not conducive for hatching.[36]

Properties

Vermicompost has been shown to be richer in many nutrients than compost produced by other composting methods.[37] It has also outperformed a commercial plant medium with nutrients added, but levels of magnesium required adjustment, as did pH.[38]

However, in one study it has been found that homemade backyard vermicompost was lower in microbial biomass, soil microbial activity, and yield of a species of ryegrass[39] than municipal compost.[39]

It is rich in microbial life which converts nutrients already present in the soil into plant-available forms.

Unlike other compost, worm castings also contain worm mucus which helps prevent nutrients from washing away with the first watering and holds moisture better than plain soil.[40]

Increases in the total nitrogen content in vermicompost, an increase in available nitrogen and phosphorus, as well as the increased removal of heavy metals from sludge and soil have been reported.[41] The reduction in the bioavailability of heavy metals has been observed in a number of studies.[42][43]

Benefits

Soil

- Improves soil aeration

- Enriches soil with micro-organisms (adding enzymes such as phosphatase and cellulase)

- Microbial activity in worm castings is 10 to 20 times higher than in the soil and organic matter that the worm ingests[44]

- Attracts deep-burrowing earthworms already present in the soil

- Improves water holding capacity[45]

Plant growth

- Enhances germination, plant growth, and crop yield

- It helps in root and plant growth

- Enriches soil organisms (adding plant hormones such as auxins and gibberellic acid)

Economic

- Biowastes conversion reduces waste flow to landfills

- Elimination of biowastes from the waste stream reduces contamination of other recyclables collected in a single bin (a common problem in communities practicing single-stream recycling)

- Creates low-skill jobs at local level

- Low capital investment and relatively simple technologies make vermicomposting practical for less-developed agricultural regions

Environmental

- Helps to close the "metabolic gap" through recycling waste on-site

- Large systems often use temperature control and mechanized harvesting, however other equipment is relatively simple and does not wear out quickly

- Production reduces greenhouse gas emissions such as methane and nitric oxide (produced in landfills or incinerators when not composted).

Uses

Soil conditioner

Vermicompost can be mixed directly into the soil, or mixed with water to make a liquid fertilizer known as worm tea.

The dark brown waste liquid, or leachate, that drains into the bottom of some vermicomposting systems is not to be confused with worm tea. It is an uncomposted byproduct from when water-rich foods break down and may contain pathogens and toxins. It is best discarded or applied back to the bin when added moisture is needed for further processing.[46][47]

The pH, nutrient, and microbial content of these fertilizers varies upon the inputs fed to worms. Pulverized limestone, or calcium carbonate can be added to the system to raise the pH.

Operation and maintenance

Smells

When closed, a well-maintained bin is odorless; when opened, it should have little smell—if any smell is present, it is earthy.[48] The smell may also depend on the type of composted material added to the bin. An unhealthy worm bin may smell, potentially due to low oxygen conditions. Worms require gaseous oxygen.[49] Oxygen can be provided by airholes in the bin, occasional stirring of bin contents, and removal of some bin contents if they become too deep or too wet. If decomposition becomes anaerobic from excess wet feedstock added to the bin, or the layers of food waste have become too deep, the bin will begin to smell of ammonia.

Moisture

Moisture must be maintained above 50%, as lower moisture content will not support worm respiration and can increase worm mortality. Operating moisture-content range should be between 70 and 90%, with a suggested content of 70-80% for vermicomposting operations.[50] If decomposition has become anaerobic, to restore healthy conditions and prevent the worms from dying, excess waste water must be reduced and the bin returned to a normal moisture level. To do this, first reduce addition of food scraps with a high moisture content and second, add fresh, dry bedding such as shredded newspaper to your bin, mixing it in well.[51]

Pest species

Pests such as rodents and flies are attracted by certain materials and odors, usually from large amounts of kitchen waste, particularly meat. Eliminating the use of meat or dairy product in a worm bin decreases the possibility of pests.[52]

Predatory ants can be a problem in African countries.[53]

In warm weather, fruit and vinegar flies breed in the bins if fruit and vegetable waste is not thoroughly covered with bedding. This problem can be avoided by thoroughly covering the waste by at least 5 centimetres (2.0 in) of bedding. Maintaining the correct pH (close to neutral) and water content of the bin (just enough water where squeezed bedding drips a couple of drops) can help avoid these pests as well.

Worms escaping

Worms generally stay in the bin, but may try to leave the bin when first introduced, or often after a rainstorm when outside humidity is high.[54] Maintaining adequate conditions in the worm bin and putting a light over the bin when first introducing worms should eliminate this problem.[55]

Nutrient levels

Commercial vermicomposters test and may amend their products to produce consistent quality and results. Because the small-scale and home systems use a varied mix of feedstocks, the nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (NPK) content of the resulting vermicompost will also be inconsistent. NPK testing may be helpful before the vermicompost or tea is applied to the garden.

In order to avoid over-fertilization issues, such as nitrogen burn, vermicompost can be diluted as a tea 50:50 with water, or as a solid can be mixed in 50:50 with potting soil.[56]

Additionally, the mucous layer created by worms which surrounds their castings allows for a "time release" effect, meaning not all nutrients are released at once. This also reduces the risk of burning the plants, as is common with the use and overuse of commercial fertilizers.[57]

Application examples

Vermicomposting is widely used in North America for on-site institutional processing of food scraps, such as in hospitals, universities, shopping malls, and correctional facilities.[58] Vermicomposting is used for medium-scale on-site institutional organic material recycling, such as for food scraps from universities and shopping malls. It is selected either as a more environmentally friendly choice than conventional disposal, or to reduce the cost of commercial waste removal.

Researchers from the Pondicherry University discovered that worm composts can also be used to clean up heavy metals. The researchers found substantial reductions in heavy metals when the worms were released into the garbage and they are effective at removing lead, zinc, cadmium, copper and manganese.[59]

See also

- Fertilizer

- Home composting

- Maggot farming

- Mary Arlene Appelhof

- Vermifilter

- Vermiponics, use of wormbin leachate in hydroponics

- Waste management

References

- 1 2 "Paper on Invasive European Worms". Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- ↑ Ndegwa, P.M.; Thompson, S.A.; Das, K.C. (1998). "Effects of stocking density and feeding rate on vermicomposting of biosolids" (PDF). Bioresource Technology. 71: 5–12. doi:10.1016/S0960-8524(99)00055-3.

- 1 2 Coyne, Kelly and Erik Knutzen. The Urban Homestead: Your Guide to Self-Sufficient Living in the Heart of the City. Port Townsend: Process Self Reliance Series, 2008.

- ↑ Xing, Meiyan; JianYang, null; Wang, Yayi; Liu, Jing; Yu, Fen (2011-01-30). "A comparative study of synchronous treatment of sewage and sludge by two vermifiltrations using an epigeic earthworm Eisenia fetida". Journal of Hazardous Materials. 185 (2–3): 881–888. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.09.103. ISSN 1873-3336. PMID 21041027.

- ↑ "Pilot studies for vermifiltration of 1000m3day of sewage wastewater". www.academia.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ↑ Lazcano, Cristina; Gómez-Brandón, María; Domínguez, Jorge (2008). "Comparison of the effectiveness of composting and vermicomposting for the biological stabilization of cattle manure" (PDF). Chemosphere. 72 (7): 1013–1019. Bibcode:2008Chmsp..72.1013L. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.04.016. PMID 18511100.

- ↑ Dominguez, Jorge; Edwards, Clive (2010-12-15), "Biology and Ecology of Earthworm Species Used for Vermicomposting", Vermiculture Technology, CRC Press, pp. 27–40, doi:10.1201/b10453-4, ISBN 978-1-4398-0987-7

- ↑ Edwards, C.A. (1998). Earthworm Ecology. CRC Press LLC. p. 189. ISBN 978-1-884015-74-8.

- ↑ Organic Phosphorus in the Environment, Turner, et al., Page 91. 2005

- ↑ Reza, Shamim (24 March 2016). "Vermicomposting – A Great Way to Turn the Burdens into Resources". Permaculture Research Institute.

- ↑ Beyers, R; MacLean, S. "Developing an educational curriculum fororganic farming and permaculture in theDistrict of Santa Fe" (PDF). La Foundación Héctor Gallego: 16.

All the permaculture farms we visited had a large, fully-functioning vermicompost which produced fertilizer that was naturally rich in nutrients and acid that was used as a substance for fumigation instead of synthetic based substances.

- ↑ "Composting Worms for Hawaii" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- ↑ "Great Lakes Worm Watch". Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- ↑ "Composting with earthworms". Herron Farms Dawsonville Ga. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ↑ Aalok, Asha; Tripathi, A.K.; Soni, P. (2008). "Vermicomposting: A Better Option for Organic Solid Waste Management" (PDF). Journal of Human Ecology. 24: 59–64. doi:10.1080/09709274.2008.11906100. S2CID 983903. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-07-01. Retrieved 2009-02-21.

- ↑ "Windrow composting systems can be feasable [sic], cost effective (Research Brief #20) | Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems". www.cias.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ↑ "Worm Compost Bins - What To Look For and What To Avoid". www.best-organic-fertilizer.com. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ↑ "Raising Earthworms Successfully" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ↑ Archived July 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Andreasheeschen. "Build your own Worm Farm". Growing Organic. Archived from the original on 2016-02-13. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ↑ "Vermiculture". www.worm-farm.co.za. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ↑ "The Worm Dictionary and Vermiculture Reference Center". Working Worms. Archived from the original on 28 October 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ Trautmann, Nancy. "Invertebrates of the Compost Pile". Cornell Center for the Environment. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ↑ "High Heat And Worm Bins – Tips For Vermicomposting When It's Hot". Gardening Know How. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ↑ Appelhof, p. 3

- ↑ Appelhof, p. 41

- 1 2 Selden, Piper; DuPonte, Michael; Sipes, Brent; Dinges, Kelly (August 2005). "Small-Scale Vermicomposting" (PDF). Home Garden. University of Hawai'i. 45. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ↑ Reinecke, SA; Reinecke, AJ (February 2007). "The impact of organophosphate pesticides in orchards on earthworms in the Western Cape, South Africa" (PDF). Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 66 (2): 244–51. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2005.10.006. PMID 16318873. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2012-09-19.

- ↑ Latest Developments In Mid-To-Large-Scale Vermicomposting Archived June 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Archived October 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Lotzof, M. "Very Large Scale Vermiculture in Sludge Stabilisation". Vermitech Pty Limited. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ↑ Smith, Kelly (2011). "Maintaining a Compost Bin". How to Build, Maintain, and Use a Compost System: Secrets and Techniques You Need to Know to Grow the Best Vegetables. Atlantic Publishing Company. pp. 163–170. ISBN 978-1-60138-354-9.

- ↑ Appelhof, pp. 79-86

- ↑ "Harvesting - MMSB - Multi-Materials Stewardship Board". MMSB - Multi-Materials Stewardship Board. Archived from the original on 2015-10-28. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ↑ "Red-wiggler Compost Worm eggs". Archived from the original on 2018-03-18. Retrieved 2018-03-18.

- ↑ "Red Worm Biology".

- ↑ Dickerson, George W. (June 2001). "Vermicomposting: Guide H-164" (PDF). New Mexico State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-01-15. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ↑ Sherman, Rhonda. "Earthworm Castings as Plant Growth Media". Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering at NCSU. Archived from the original on 2006-01-17. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- 1 2 Lazcano, Cristina; Gómez-Brandón, María; Domínguez, Jorge (July 2008). "Comparison of the effectiveness of composting and vermicomposting for the biological stabilization of cattle manure" (PDF). Chemosphere. 72 (7): 1013–1019. Bibcode:2008Chmsp..72.1013L. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.04.016. PMID 18511100.

- ↑ Nancarrow, Loren; Taylor, Janet Hogan (1998). The Worm Book: The Complete Guide to Gardening and Composting with Worms Archived March 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Ten Speed Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-89815-994-3.

- ↑ Liu, Fei; Zhu, Pengfei; Xue, Jianping (2012-01-01). "Comparative Study on Physical and Chemical Characteristics of Sludge Vermicomposted by Eisenia Fetida". Procedia Environmental Sciences. The Seventh International Conference on Waste Management and Technology (ICWMT 7). 16: 418–423. doi:10.1016/j.proenv.2012.10.058.

- ↑ Song, Xiuchao; Liu, Manqiang; Wu, Di; Qi, Lin; Ye, Chenglong; Jiao, Jiaguo; Hu, Feng (2014-11-01). "Heavy metal and nutrient changes during vermicomposting animal manure spiked with mushroom residues". Waste Management (New York, N.Y.). 34 (11): 1977–1983. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2014.07.013. ISSN 1879-2456. PMID 25128918.

- ↑ Kharrazi, Seyede Maryam; Younesi, Habibollah; Abedini-Torghabeh, Javad (2014). "Microbial biodegradation of waste materials for nutrients enrichment and heavy metals removal: An integrated composting-vermicomposting process". International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation. 92: 41–48. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2014.04.011.

- ↑ Logsdon, Gene (October 1994). "Worldwide progress in vermicomposting". BioCycle. 35 (10): 63.

- ↑ Appelhof, p. 111

- ↑ Sherman, Rhonda. "Raising Earthworms Successfully" (PDF). infohouse.p2ric.org. North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-16. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- ↑ Uncle Jim (6 January 2015). "How are Worm Tea and Worm Leachate Different?". unclejimswormfarm.com. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- ↑ Appelhof, p. 113

- ↑ Appelhof, p. 92

- ↑ "Manual of On-Farm Vermicomposting and Vermiculture" (PDF). p. 14. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- ↑ Nancarrow, Loren; Taylor, Janet Hogan (1998). The Worm Book: The Complete Guide to Gardening and Composting with Worms Archived March 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Ten Speed Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-89815-994-3.

- ↑ "Manual of On-Farm Vermicomposting and Vermiculture" (PDF). p. 8. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- ↑ David Watako; Koslengar Mougabe; Thomas Heath (April 2016). "Tiger worm toilets: lessons learned from constructing household vermicomposting toilets in Liberia". Waterlines. 35 (2): 136–147. doi:10.3362/1756-3488.2016.012.

- ↑ Compost Worm Escape

- ↑ Can you do vermicomposting in an apartment? Archived October 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Grant, Tim; Littlejohn, Gail (2004). Teaching Green, The Middle Years. Gabriola Island, B.C.: New Society Publishers. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-86571-501-1.

- ↑ "Compost or Worm Castings?". Big Red Worms. Retrieved 2018-04-23.

- ↑ Edwards, Clive A. (2010). Vermiculture Technology. CRC Press. pp. 392–406. ISBN 978-1-4398-0987-7.

- ↑ Cleaning up heavy metals using worms, International: mining.com, 2012, retrieved 3 October 2012

Further reading

- Appelhof, Mary (2007). Worms Eat My Garbage (2nd ed.). Kalamazoo, Mich.: Flowerfield Enterprises. ISBN 978-0-9778045-1-1.

- Sherman, Rhonda (October 18, 2016). Raising Earthworms Successfully. content.ces.ncsu.edu (Report). Vol. AG-641. NC State Extension Publications. Retrieved 2018-12-24.

External links

Learning materials related to Vermicompost at Wikiversity

Learning materials related to Vermicompost at Wikiversity