Congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy

| Congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Maumenee corneal dystrophy[1] | |

| |

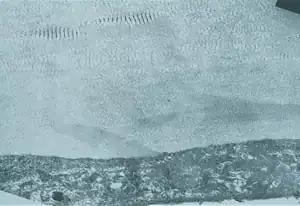

| A markedly opaque cornea due to corneal edema secondary to defective endothelial cells (Courtesy of Dr. Ahmed A. Hidajat) | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

Congenital hereditary corneal dystrophy (CHED) is a form of corneal endothelial dystrophy that presents at birth.

CHED was previously subclassified into two subtypes: CHED1 and CHED2. However in 2015, the International Classification of Corneal Dystrophies (IC3D) renamed the condition "CHED1" to become posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy, and renamed the condition "CHED2" to become, simply, CHED.[2] Consequently, the scope of this article is restricted to the condition currently referred to as CHED

Signs and symptoms

CHED presents congenitally, but has a stationary course. The cornea exhibits a variable degree of clouding: from a diffuse haze, to a "ground glass" appearance, with occasional focal gray spots. The cornea thickens to between two and three times is normal thickness. Rarely, sub-epithelial band keratopathy and elevated intraocular pressure occur. Patients have blurred vision and nystagmus, however it is rare for the condition to be associated with either epiphora or photophobia with this.[1]

Genetics

CHED exhibits autosomal recessive inheritance, with 80% of cases linked to mutations in SLC4A11 gene. The SLC4A11 gene encodes solute carrier family 4, sodium borate transporter, member 11.[1]

Pathology

Histologically, the Descemet's membrane in CHED becomes diffusely thickened and laminated. Multiple layers of basement membrane-like material appear to form on the posterior part of Descemet's membrane. The endothelial cells are sparse - they become atrophic and degenerated, with many vacuoles.

The corneal stroma becomes severely disorganised; the lamellar arrangement of the fibrils becomes disrupted.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of this condition can be done via the fluoro-photometrical method.[3]

Management

Management of CHED primarily involves corneal transplantation. The age that corneal transplantation is required is variable, however, it is usually necessary fairly early in life.[1]

See also

- Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (for the condition previously referred to as CHED1)

- Corneal dystrophy

References

- 1 2 3 4 Bowes Hamill, M. (2015). 2015-2016 Basic and Clinical Science Course (BCSC): Refractive Surgery Section 13. ISBN 978-1615256570.

- ↑ Weiss, Jayne S.; Møller, Hans Ulrik; Aldave, Anthony J.; Seitz, Berthold; Bredrup, Cecilie; Kivelä, Tero; Munier, Francis L.; Rapuano, Christopher J.; Nischal, Kanwal K.; Kim, Eung Kweon; Sutphin, John; Busin, Massimo; Labbé, Antoine; Kenyon, Kenneth R.; Kinoshita, Shigeru; Lisch, Walter (February 21, 2015). "IC3D classification of corneal dystrophies--edition 2". Cornea. 34 (2): 117–159. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000000307. hdl:11392/2380137. PMID 25564336.

- ↑ Moshirfar, Majid; Drake, Taylor M.; Ronquillo, Yasmyne (2021). "Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- Vithana EN; et al. (July 2006). "Mutations in sodium-borate cotransporter SLC4A11 cause recessive congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED2)". Nat. Genet. 38 (7): 755–7. doi:10.1038/ng1824. PMID 16767101.

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 217700

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 121700

Template:Human corneal dystrophy

| Classification |

|---|