Conjoined twins

| Conjoined twins | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Siamese twins |

| |

| X-ray of conjoined twins, Cephalothoracopagus. | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

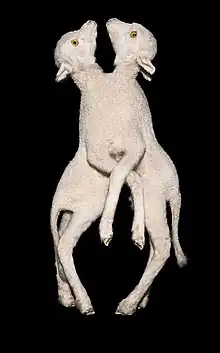

Conjoined twins – sometimes popularly referred to as Siamese twins[1][2] – are identical twins[3] joined in utero. A very rare phenomenon, the occurrence is estimated to range from 1 in 49,000 births to 1 in 189,000 births, with a somewhat higher incidence in Southwest Asia and Africa.[4] Approximately half are stillborn, and an additional one-third die within 24 hours. Most live births are female, with a ratio of 3:1.[4][5]

Two contradicting theories exist to explain the origins of conjoined twins. The more generally accepted theory is fission, in which the fertilized egg splits partially.[6] The other theory, no longer believed to be the basis of conjoined twinning,[6] is fusion, in which a fertilized egg completely separates, but stem cells (which search for similar cells) find similar stem cells on the other twin and fuse the twins together. Conjoined twins share a single common chorion, placenta, and amniotic sac, although these characteristics are not exclusive to conjoined twins, as there are some monozygotic but non-conjoined twins who also share these structures in utero.[7]

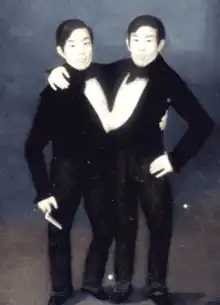

Chang and Eng Bunker (1811–1874) were brothers born in Siam (now Thailand) who traveled widely for many years and were labeled as The Siamese Twins. Chang and Eng were joined at the torso by a band of flesh, cartilage, and their fused livers. In modern times, they could have been easily separated.[8] Due to the brothers' fame and the rarity of the condition, the term "Siamese twins" came to be associated with conjoined twins.

Causes

There are two theories about the development of conjoined twins. The first is that a single fertilized egg does not fully split during the process of forming identical twins. If the zygote division occurs after two weeks of the development of the embryonic disc, it results in the formation of conjoined twins.[9] The second theory is that a fusion of two fertilized eggs occurs earlier in development.

Partial splitting of the primitive node and streak may result in the formation of conjoined twins. These twins are classified according to the nature and degree of their union. Occasionally, monozygotic twins are connected only by a common skin bridge or by a common liver bridge. The type of twins formed depends on when and to what extent abnormalities of the node and streak occurred. Misexpression of genes, such as Goosecoid, may also result in conjoined twins.[10] Goosecoid activates inhibitors of BMP4 and contributes to regulation of head development. Over- or underexpression of this gene in laboratory animals results in severe malformations of the head region, including duplications, similar to some types of conjoined twins.[11]

Types

Conjoined twins are typically classified by the point at which their bodies are joined. The most common types of conjoined twins are:

- Thoraco-omphalopagus (28% of cases):[6] Two bodies fused from the upper chest to the lower chest. These twins usually share a heart and may also share the liver or part of the digestive system.[12]

- Thoracopagus (18.5%):[6] Two bodies fused from the upper chest to lower belly. The heart is always involved in these cases.[12] As of 2015, separation of a genuinely shared heart has not offered survival to two twins; a designated twin may survive if allotted the heart, sacrificing the other twin.

- Omphalopagus (10%):[6] Two bodies fused at the lower abdomen. Unlike thoracopagus, the heart is never involved in these cases; however, the twins often share a liver, digestive system, diaphragm and other organs.[12]

- Parasitic twins (10%):[6] Twins that are asymmetrically conjoined, resulting in one twin that is small, less formed, and dependent on the larger twin for survival.

- Craniopagus (6%):[6] Fused skulls, but separate bodies. These twins can be conjoined at the back of the head, the front of the head, or the side of the head, but not on the face or the base of the skull.[12]

Other, less common types of conjoined twins include:

- Cephalopagus: Two faces on opposite sides of a single, conjoined head; the upper portion of the body is fused while the bottom portions are separate. These twins generally cannot survive due to severe malformations of the brain. Also known as janiceps (after the two-faced Roman deity Janus).[12]

- Syncephalus: One head with a single face but four ears, and two bodies.[12]

- Cephalothoracopagus: Bodies fused in the head and thorax. In this type of twins, there are two faces facing in opposite directions, or sometimes a single face and an enlarged skull.[12][13]

- Xiphopagus: Two bodies fused in the xiphoid cartilage, which is approximately from the navel to the lower breastbone. These twins almost never share any vital organs, with the exception of the liver.[12] A famous example is Chang and Eng Bunker.

- Ischiopagus: Fused lower half of the two bodies, with spines conjoined end-to-end at a 180° angle. These twins have four arms; one, two, three or four legs; and typically one external set of genitalia and anus.[12]

- Omphalo-Ischiopagus: Fused in a similar fashion to ischiopagus twins, but facing each other with a joined abdomen akin to omphalopagus. These twins have four arms, and two, three, or four legs.[12]

- Parapagus: Fused side by side with a shared pelvis. Twins that are dithoracic parapagus are fused at the abdomen and pelvis, but not the thorax. Twins that are diprosopic parapagus have one trunk and two faces. Twins that are dicephalic parapagus have one trunk and two heads, and have two (dibrachius), three (tribrachius), or four (tetrabrachius) arms.[12]

- Craniopagus parasiticus: Like craniopagus, but with a second bodiless head attached to the dominant head.

- Pygopagus or Iliopagus: Two bodies joined at the pelvis.[12]

- Rachipagus: Twins joined along the back of their bodies, with fusion of the vertebral arches and the soft tissue from the head to the buttocks[14]

Management

Separation

Surgery to separate conjoined twins may range from very easy to very difficult depending on the point of attachment and the internal parts that are shared. Most cases of separation are extremely risky and life-threatening. In many cases, the surgery results in the death of one or both of the twins, particularly if they are joined at the head or share a vital organ. This makes the ethics of surgical separation, where the twins can survive if not separated, contentious. Alice Dreger of Northwestern University found the quality of life of twins who remain conjoined to be higher than is commonly supposed.[15] Lori and George Schappell and Abby and Brittany Hensel are notable examples.

The first record of separating conjoined twins took place in the Byzantine Empire in the 900s. One of the conjoined twins had already died, so the doctors of the town attempted to separate the dead twin from the surviving twin. The result was partly successful as the remaining twin lived for three days after separation. The next case of separating conjoined twins was recorded in 1689 in Germany several centuries later.[16][17] The first recorded successful separation of conjoined twins was performed in 1689 by Johannes Fatio.[18] In 1955, neurosurgeon Harold Voris (1902-1980)[19] and his team at Mercy Hospital in Chicago performed the first successful operation to separate craniopagus twins (conjoined at the head), which resulted in long-term survival for both.[20][21][22] The larger girl was reported in 1963 as developing normally, but the smaller was permanently impaired.[23]

In 1957, Bertram Katz and his surgical team made international medical history performing the world's first successful separation of conjoined twins sharing a vital organ.[24] Omphalopagus twins John Nelson and James Edward Freeman (Johnny and Jimmy) were born in Youngstown, Ohio, on April 27, 1956. The boys shared a liver but had separate hearts and were successfully separated at North Side Hospital in Youngstown, Ohio, by Bertram Katz. The operation was funded by the Ohio Crippled Children's Service Society.[25]

Recent successful separations of conjoined twins include that of the separation of Ganga and Jamuna Shreshta in 2001, who were born in Kathmandu, Nepal, in 2000. The 97-hour surgery on the pair of craniopagus twins was a landmark one which took place in Singapore; the team was led by neurosurgeons Chumpon Chan and Keith Goh.[26] The surgery left Ganga with brain damage and Jamuna unable to walk. Seven years later, Ganga Shrestha died at the Model Hospital in Kathmandu in July 2009, at the age of eight, three days after being admitted for treatment of a severe chest infection.[27]

Infants Rose and Grace Attard, conjoined twins from Malta, were separated in the United Kingdom by court order Re A over the religious objections of their parents, Michaelangelo and Rina Attard. The twins were attached at the lower abdomen and spine. The surgery took place in November 2000, at St Mary's Hospital in Manchester. The operation was controversial because Rose, the weaker twin, would die as a result of the procedure as her heart and lungs were dependent upon Grace's. However, if the operation had not taken place, it was certain that both twins would die.[28][29] Grace survived to enjoy a normal childhood.[30]

In 2003, two 29-year-old women from Iran, Ladan and Laleh Bijani, who were joined at the head but had separate brains (craniopagus) were surgically separated in Singapore, despite surgeons' warnings that the operation could be fatal to one or both. Their complex case was accepted only because technologically advanced graphical imagery and modeling would allow the medical team to plan the risky surgery. However, an undetected major vein hidden from the scans was discovered during the operation.[31] The separation was completed but both women died while still in surgery.

In 2019 Safa and Marwa Ullah were separated at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London, England. The twins, born January 2017 were joined at the top of the head with separate brains and a cylindrical shared skull with the twins each facing in opposite directions to one another. The surgery was jointly led by neurosurgeon Owase Jeelani and plastic surgeon Professor David Dunaway. The surgery presented particular difficulties due to a number of shared veins and a distortion in the shape of the girls' brains, causing them to overlap. The distortion would need to be corrected in order for the separation to go ahead. The surgery utilized a team of more than 100 including bio engineers, 3D modelers and a virtual reality designer. The separation was completed in February 2019 following a total of 52 hours of surgery over three separate operations. As of July 2019, both girls remain healthy and the family planned to return to their home in Pakistan in 2020.[32][33]

History

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The Moche culture of ancient Peru depicted conjoined twins in their ceramics dating back to 300 CE.[34] Writing around 415 CE, St. Augustine of Hippo, in his book, City of God, refers to a man "double in his upper, but single in his lower half--having two heads, two chests, four hands, but one body and two feet like an ordinary man."[35]

According to Theophanes the Confessor, a Byzantine historian of the 9th century, around 385/386 CE, "in the village of Emmaus in Palestine, a child was born perfectly normal below the navel but divided above it, so that it had two chests and two heads, each possessing the senses. One would eat and drink but the other did not eat; one would sleep but the other stayed awake. There were times when they played with each other, when both cried and hit each other. They lived for a little over two years. One died while the other lived for another four days and it, too, died."[36]

In Arabia, the twin brothers Hashim ibn Abd Manaf and 'Abd Shams were born with Hashim's leg attached to his twin brother's head. Legend says that their father, Abd Manaf ibn Qusai, separated his conjoined sons with a sword and that some priests believed that the blood that had flowed between them signified wars between their progeny (confrontations did occur between Banu al'Abbas and Banu Ummaya ibn 'Abd Shams in the year 750 AH).[37] The Muslim polymath Abū al-Rayhān al-Bīrūnī described conjoined twins in his book Kitab-al-Saidana.[38]

The English twin sisters Mary and Eliza Chulkhurst, who were conjoined at the back (pygopagus), lived from 1100 to 1134 (or 1500 to 1534) and were perhaps the best-known early historical example of conjoined twins. Other early conjoined twins to attain notice were the "Scottish brothers", allegedly of the dicephalus type, essentially two heads sharing the same body (1460–1488, although the dates vary); the pygopagus Helen and Judith of Szőny, Hungary (1701–1723), who enjoyed a brief career in music before being sent to live in a convent; and Rita and Cristina of Parodi of Sardinia, born in 1829. Rita and Cristina were dicephalus tetrabrachius (one body with four arms) twins and although they died at only eight months of age, they gained much attention as a curiosity when their parents exhibited them in Paris.

Several sets of conjoined twins lived during the nineteenth century and made careers for themselves in the performing arts, though none achieved quite the same level of fame and fortune as Chang and Eng. Most notably, Millie and Christine McCoy (or McKoy), pygopagus twins, were born into slavery in North Carolina in 1851. They were sold to a showman, J.P. Smith, at birth, but were soon kidnapped by a rival showman. The kidnapper fled to England but was thwarted because England had already banned slavery. Smith traveled to England to collect the girls and brought with him their mother, Monimia, from whom they had been separated. He and his wife provided the twins with an education and taught them to speak five languages, play music, and sing. For the rest of the century, the twins enjoyed a successful career as "The Two-Headed Nightingale" and appeared with the Barnum Circus. In 1912, they died of tuberculosis, 17 hours apart.

Giovanni and Giacomo Tocci, from Locana, Italy, were immortalized in Mark Twain's short story "Those Extraordinary Twins" as fictitious twins Angelo and Luigi. The Toccis, born in 1877, were dicephalus tetrabrachius twins, having one body with two legs, two heads, and four arms. From birth they were forced by their parents to perform and never learned to walk, as each twin controlled one leg (in modern times, physical therapy allows twins like the Toccis to learn to walk on their own). They are said to have disliked show business. In 1886, after touring the United States, the twins returned to Europe with their family. They are believed to have died around this time, though some sources claim they survived until 1940, living in seclusion in Italy.

Notable people

Born 19th century and earlier

- Mary and Eliza Chulkhurst, alleged names of the Biddenden Maids (per tradition, born in the 12th century) of Kent, England.[39] They are the earliest set of conjoined twins whose names are (purportedly) known.

- Lazarus and Joannes Baptista Colloredo (1617 — 1646?), autosite-and-parasite pair

- Helen and Judith of Szony (Hungary, 1701 — 1723), pygopagus.

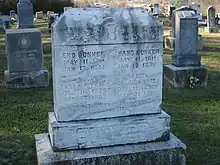

- Chang and Eng Bunker (1811 — 1874). The Bunker twins were born of Chinese origin in Siam (now Thailand), and the expression Siamese twins is derived from their case. They were joined by the areas around their xiphoid cartilages, but over time, the connective tissue stretched.

- Millie and Christine McCoy (11 July 1851 – 8 October 1912), (oblique pygopagus). The McCoy twins were born into slavery in Columbus County, North Carolina, United States. They went by the stage names "The Two-Headed Nightingale" and "The Eighth Wonder of the World" and had an extensive career before retiring to the farm on which they were born.

- Giacomo and Giovanni Battista Tocci (1875? — 1912?), (dicephalus tetrabrachius dipus)

- Josefa and Rosa Blazek (20 January 1878 — 30 March 1922),[40] pygopagus.[41] The Blazek twins were born in Skrejšov, Bohemia (now the Czech Republic).[41] They began performing in public exhibitions at the age of 13, and their act later included Rosa’s son Franz. The sisters died in Chicago, Illinois.[42]

Born 20th century

- Daisy and Violet Hilton of Brighton, England (1908–1969), pygopagus. The Hilton twins were performers who played musical instruments, sang, and danced. At the height of their career, they had the highest paid act in vaudeville.[43] They also appeared in the movies Freaks and Chained for Life.

- Lucio and Simplicio Godina of Samar, Philippines (1908–1936)

- Masha and Dasha Krivoshlyapova of Moscow, Russia (1950–2003), the rarest form of conjoined twins, one of few cases of dicephalus tetrabrachius tripus (two heads, four arms, three legs)

- Ronnie and Donnie Galyon of Ohio (1951–2020), omphalopagus

- Tjitske and Folkje de Vries of Mûnein, Netherlands (b. 1953)

- Wariboko and Tamunotonye Davies, born 25 July 1953 in Kano, Nigeria. Separated in London by a team led by Ian Aird. Tamunotonye died postoperatively. Wariboko became a nurse.[44]

- Lori and George Schappell, born September 18, 1961, in Reading, Pennsylvania, American entertainers, craniopagus

- Ganga and Jamuna Mondal of India, born 1969 or 1970, known professionally as The Spider Girls and The Spider Sisters. Ischiopagus.

- Anna and Barbara Rozycki (born 1970), the first conjoined twins successfully separated.

- Ma Nan Soe and Ma Nan San (born 1971 in Myanmar), separated in July 1971 at Yangon Pediatric Hospital. They were joined from chest to belly button. Ma Nan San died after one month and seven days after operation.

- Elisa and Lisa Hansen, Ogden, Utah (1977-2020). Born by Caesarean section on 18 October 1977, were conjoined at the top of their head (craniopagus). They were separated 1979 after 16-hour surgery, were first to both survive surgery.

- Ladan and Laleh Bijani of Shiraz, Iran (1974–2003); died during separation surgery in Singapore. Craniopagus.

- Baby Girl A and Baby Girl B (born 1977 in New Jersey) shared a single six-chambered heart. Separation surgery, led by C. Everett Koop, involved the instant death of Baby Girl A; the difficult ethical and religious concerns generated significant local newspaper coverage. Baby Girl B survived for 3 months.[45]

- Viet and Duc Nguyen, born on February 25, 1981, in Kon Tum Province, Vietnam, and separated in 1988 in Ho Chi Minh City. Viet died on October 6, 2007. Ischiopagus.

- Maria and Consolata Mwakikuti of Tanzania (1986?–2018); conjoined by the abdomen; died of respiratory problems resulting from an abnormal, inoperable chest deformity.[46]

- Patrick and Benjamin Binder, separated in 1987 by team of doctors led by Ben Carson. Craniopagus.

- Andrew and Alex Olson, born in 1987, separated in April 1988 at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Omphalopagus. Alex died in 2018.

- Katie and Eilish Holton, born August 1988 in Ireland; Katie died after separation due to cardiac arrest at the age of 3,5 years.

- Abigail and Brittany Hensel are dicephalic parapagus twins born on March 7, 1990 in Carver County, Minnesota. Both graduated in 2012 from Bethel University, St. Paul, hired as teachers.

- Tiesha and Iesha Turner (born 1991 in Texas), separated in 1992 at Texas Children's Hospital in Houston, Texas. Omphalopagus.

- Ashley and Ashil Fokeer, born on 2 November 1992 in Mauritius[47]

- Joseph and Luka Banda (born January 23, 1997, in Zambia), separated in 1997 in South Africa by Ben Carson (with a later intervention in 2001 to artificially close their skulls). Craniopagus.

- Maria del Carmen Andrade Solis and Maria Guadalupe Andrade Solis (better known as Carmen and Lupita) were born in June 2000 in Veracruz, Mexico. They later moved to the United States for healthcare with their parents.[48]

Born 21st century

- Carl and Clarence Aguirre, born with vertical craniopagus in Silay City, Negros Occidental, on April 21, 2002. They were successfully separated on August 4, 2004.[49]

- Tabea and Lea Block, from Lemgo, Germany, were born as craniopagus twins joined on the tops of their heads on August 9, 2003. The girls shared some major veins, but their brains were separate. They were separated on September 16, 2004, although Tabea died about 90 minutes later.[50]

- Anastasia and Tatiana Dogaru, born outside Rome in Lazio, Italy, on January 13, 2004. As craniopagus twins, the top of Tatiana's head is attached to the back of Anastasias's head.

- Lakshmi Tatma (born 2005) was an ischiopagus conjoined twin born in Araria district in the state of Bihar, India. She had four arms and four legs, resulting from a joining at the pelvis with a headless undeveloped parasitic twin.[51]

- On 2005 a set of conjoined triplets was detected, characterized as tricephalus, tetrabrachius, and tetrapus parapagothoracopagus, and the pregnancy interrupted at 22 weeks.[52]

- Kendra and Maliyah Herrin, ischiopagus twins separated in 2006 at age 4[53]

- Krista and Tatiana Hogan, Canadian twins conjoined at the head. Born October 25, 2006. Share part of their brain and can pass sensory information and thoughts between each other.

- Trishna and Krishna from Bangladesh were born in December 2006. They are craniopagus twins, joined on the tops of their skulls and sharing a small amount of brain tissue. In 2009, they were separated in Melbourne, Australia.[54]

- Maria and Teresa Tapia, born in the Dominican Republic on April 8, 2010. Conjoined by the liver, pancreas, and a small portion of their small intestine. Separation occurred on November 7, 2011 at Children's Hospital of Richmond at VCU.

- Aung Myat Kyaw and Aung Khant Kyaw (born in May 2011, Mandalay, Myanmar), connected at pelvis.

- Jesus and Emanuel de Nazaré are dicephalic parapagus twins born in Pará, Brazil on December 19, 2011.

- Zheng Han Wei and Zheng Han Jing, born in China on August 11, 2013. Conjoined by their sternum, pericardium, and liver. In 2014, they were separated in Shanghai, China, at the Shanghai Children's Medical Center.[55][56]

- Asa and Eli Hamby were born in 2014 in Georgia but died less than two days after birth due to heart failure. The twins were dicephalic parapagus having two heads but being conjoined at the torso, arms and legs. They had separate spinal columns but one heart making postnatal operations impossible.

- Jadon and Anias McDonald, born in September 2015. Conjoined by the head. Successfully separated at Children's Hospital of Montefiore Medical Center by James T. Goodrich in October 2016.[57][58]

- Erin and Abby Delaney, born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania USA on July 24, 2016. Conjoined by the head. They were successfully separated at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia on June 16, 2017.[59]

- Marieme and Ndeye Ndiaye, twin girls born in Senegal in 2017, living in Cardiff, UK in 2019[60]

- Safa and Marwa Bibi, twin girls born in Hayatabad, Pakistan on January 17, 2017, conjoined by the head. Successfully separated at Great Ormond Street Hospital in February 2019.

- Callie and Carter Torres, born 30 January 2017 in Houston Texas, from Blackfoot Idaho. They are Omphalo-Ischiopagus conjoined twins, attached by their pelvic area and sharing all organs from the belly button down with just one leg each.[61][62]

- Yiḡit and Derman Evrensel, twin boys born on 21 June 2018, Antalya, Turkey. They are craniopagus twins and were separated at Great Ormond Street Hospital in 2019 by the same surgeons that separated Safa and Marwa Bibi.[63][64]

- Ervina and Prefina, born June 29, 2018 in the Central African Republic. They were separated on June 5, 2020 at the Bambino Gesù Pediatric Hospital in Rome, Italy.[65]

- Mercy and Goodness Ede, born August 13, 2019, conjoined by the chest and abdomen. Successfully separated at the National Hospital in Abuja, Nigeria in November 2019.[66]

- Marie-Cléa and Marie-Cléanne Papillon, born in Mauritius in 2019.[67] Conjoined from neck to abdomen, but also from heart which had seven rooms, instead of four.[68]. Marie-Cléa did not survive the surgery to separate the two.[69]

- Susannah and Elizabeth Castle, born April 22, 2021 and separated December 10th, 2021 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[70]

In fiction

Conjoined twins have been the focus of several noteworthy works of entertainment, including:

- Irish author Sarah Crossan won the Carnegie Medal for her verse novel, One.[71] The story follows the life and survival of conjoined twin sisters. The book also won The Bookseller's 2016 prize for young adult fiction and the Irish Children's Book of the Year.

- The Broadway musical Side Show depicts the lives of real-life conjoined twins Daisy and Violet Hilton, portrayed in the original Broadway production by Alice Ripley and Emily Skinner.

- The Peach Tree, a Korean novel and film, portrays conjoined twin brothers falling in love with the same woman.

- The 1999 movie Twin Falls Idaho portrays conjoined twin brothers who are played by two non-conjoined identical twin brothers, one of whom directed the film, and both of whom co-wrote the screenplay.

- In the fourth season of the American television series American Horror Story titled American Horror Story: Freak Show, the main character Bette and Dot Tattler (Sarah Paulson in a dual role) are a dicephalic parapagus twin where their two heads are side by side on one torso. This performance is done with the help of CGI.

- Brian Aldiss's 1977 novel Brothers of the Head depicts conjoined twins who become rock stars. In the 2005 film adaptation, they are played by non-conjoined identical twins Harry Treadaway and Luke Treadaway.

See also

References

- ↑ "conjoined twin". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-11-05.

- ↑ "Medical Definition of Conjoined twin". MedicineNet. Retrieved 2021-11-05.

- ↑ "Conjoined Twins haFacts". University of Maryland Medical Center. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 6 Jan 2012.

- 1 2 Carnevale, Francisco Cesar; Borges, Marcus Vinicius; Affonso, Breno Boueri; Pinto, Ricardo Augusto de Paula; Tannuri, Uenis; Maksoud, João Gilberto (April 2006). "Importance of angiographic study in preoperative planning of conjoined twins: case report". Clinics. 61 (2): 167–70. doi:10.1590/S1807-59322006000200013. PMID 16680335.

- ↑ Conjoined Twins at eMedicine

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kaufman, M.H. (August 2004). "The embryology of conjoined twins". Child's Nervous System. 20 (8–9): 508–25. doi:10.1007/s00381-004-0985-4. PMID 15278382. S2CID 206964928.

- ↑ Tao Le; Bhushan, Vikas; Vasan, Neil (2010). First Aid for the USMLE Step 1: 2010 20th Anniversary Edition. USA: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-07-163340-6.

- ↑ "h2g2 - Twins - A369434". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑ Konar, Hiralal (10 May 2015). DC Dutta's textbook of obstetrics (Eighth ed.). p. 233. ISBN 9789351527237.

- ↑ Sadler, Thomas W. (29 October 2018). Langman's medical embryology (14th ed.). p. 124. ISBN 9781496383907.

- ↑ Sadler, Thomas W. (29 October 2018). Langman's medical embryology (14th ed.). p. 63. ISBN 9781496383907.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Burmagina, Yuliya (March 1, 2006). "Duplicata incompleta, dicephalus dipus dibrachius". TheFetus.net. Archived from the original on August 19, 2009.

- ↑ "Cephalothoracopagus Menosymmetro (Conjoined Twins)". collphyphil.org. Mütter Museum, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Archived from the original on 2010-08-15. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑ Spencer, Rowena (December 1995). "Rachipagus conjoined twins: They really do occur!". Teratology. 52 (6): 346–356. doi:10.1002/tera.1420520605. PMID 8711621.

- ↑ Dreger, Alice Domurat (2004). One of Us: Conjoined Twins and the Future of Normal. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01825-9.

- ↑ "The Case of Conjoined Twins in 10th Century Byzantium". Medievalists.net. 4 January 2014.

- ↑ Montandon, Denys (2015). "The unspeakable history of Thoracopagus twins' separation" (PDF). ISAPS News. 9 (3): 47–48.

- ↑ Kompanje, Erwin J. O. (1 December 2004). "The First Successful Separation of Conjoined Twins in 1689: Some Additions and Corrections". Twin Research. 7 (6): 537–541. doi:10.1375/1369052042663760. PMID 15607002.

- ↑ "Voris, Harold C." The University of Chicago Photographic Archive. 1972. Retrieved 2017-07-30.

- ↑ Stone, James L.; Goodrich, James T. (1 May 2006). "The craniopagus malformation: classification and implications for surgical separation". Brain. 129 (5): 1084–1095. doi:10.1093/brain/awl065. PMID 16597654.

- ↑ "Mercy Care Firsts". Mercy Hospital & Medical Center Chicago. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Separate Siamese Twins!". Chicago Tribune. April 22, 1955. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ↑ Voris, Harold C. (February 1963). "Cranioplasty in a Craniopagus Twin". Journal of Neurosurgery. 20 (2): 145–147. doi:10.3171/jns.1963.20.2.0145. PMID 14192083. S2CID 37985174.

- ↑ "Dr. Bewrtram Katz, 83 - Obituary". Vindy.com. Archived from the original on 2013-11-10. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑

- ↑ "In Conversation with Medicine's Miracle Workers -- Dr Chumpon Chan and Dr Keith Goh". Channel News Asia Singapore. April 19, 2001. Archived from the original on January 14, 2011. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ↑ "Nepali twin dies 7 years after 97-hour separation surgery". Monsters and Critics. July 30, 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-11-01.

- ↑ "Siamese twin Jodie 'to go home soon'". BBC News. April 23, 2001. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ↑ Appel, Jacob M. (September 2000). "Ethics: English High Court Orders Separation of Conjoined Twins". The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 28 (3): 312–313. doi:10.1111/j.1748-720x.2000.tb00678.x. PMID 11210387. S2CID 36191724.

- ↑ "We don't know how to tell Gracie her sister died so she could live". The Mirror. July 9, 2007. Retrieved 2014-08-03 – via Free Online Library.

- ↑ "Wired 11.10: Till Death Do Us Part". Wired. 2001-04-11. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑ "The battle to separate Safa and Marwa". BBC News. Retrieved 2019-07-18.

- ↑ "Separating conjoined twins". www.gosh.nhs.uk. Retrieved 2019-07-18.

- ↑ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- ↑ "CHURCH FATHERS: City of God, Book XVI (St. Augustine)". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑ The Chronicle of Theophanes Confessor. Byzantine and Near Eastern History, AD 284-813. Translated with Introduction and Commentary by Cyril Mango and Roger Scott. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997, p. 106-107.

- ↑ The Life of the Prophet Muhammad: Al-Sira Al-Nabawiyya By Ibn Kathir, Trevor Le Gassick, Muneer Fareed, pg. 132

- ↑ A. Zahoor (1997), Abu Raihan Muhammad al-Biruni, Hasanuddin U

- ↑ Bondeson, Jan (April 1992), "The Biddenden Maids: a curious chapter in the history of conjoined twins", Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, London: Royal Society of Medicine Press, 85 (4): 217–221, PMC 1294728, PMID 1433064

- ↑ Hartzman, Marc (2005). American Sideshow: An Encyclopedia of History's Most Wondrous and Curiously Stranger Performers. New York, NY: Jeremy P. Tarcher / Penguin. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-1585425303.

- 1 2 "The Double Monster Rosa-Josepha Blazek". The American Naturalist. 25 (298): 891–894. 1891-10-01. doi:10.1086/275418. ISSN 0003-0147.

- ↑ Breakstone, Benjamin H. (August 1922). "The Last Illiness of the Blazek Grown-Together Twins". Illinois Medical Journal. 42: 123–130 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Miller, Sarah (2021). Violet and Daisy: The Story of Vaudeville's Famous Conjoined Twins. New York: Schwartz & Wade Books. p. 221. ISBN 978-0593119723.

- ↑ "WARIBOKO OKI @ 62: Nigeria's celebrated Siamese twin tells her life story". Vanguard News. 2015-12-12. Retrieved 2018-09-02.

- ↑ "Siamese Twins: The Surgery: An Agonizing Choice - Parents, Doctors, Rabbis In Dilemma". Philadelphia Inquirer (reprinted). 1977-10-16. Archived from the original on 2020-11-26. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ↑ "Tanzanian conjoined twins die at age 21". CNN.com. 2018-06-04. Retrieved 2020-01-09.

- ↑ Vencatareddy-Nursingen, Selvanee (2019-01-08). "Naissance de bébés siamois: émouvante rencontre entre les Papillon et les Fokeer" [Birth of Siamese babies: A Moving Encounter Between the Papillons and the Fokeers]. lexpress.mu (in French). Retrieved 2019-12-18.

- ↑ "Conjoined Twins Refuse to Be Separated Despite Doctor's Warnings". PEOPLE.com. 2017-04-22. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- ↑ Staffenberg, David A.; Goodrich, James T. (January 2005). "Separation of craniopagus conjoined twins: an evolution in thought". Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 32 (1): 25–34. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2004.09.002. PMID 15636762.

- ↑ "Der Geburtstag der siamesischen Zwillinge Lea und Tabea jährt sich zum zweiten Mal". Mennonews.de (in German). August 3, 2005. Retrieved 2016-12-09.

- ↑ "Many-limbed India girl in surgery". BBC News. 2007-11-06.

- ↑ Athanasiadis, Apostolos P.; Tzannatos, Christinne; Mikos, Themistoklis; Zafrakas, Menelaos; Bontis, John N. (June 2005). "A unique case of conjoined triplets". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 192 (6): 2084–2087. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.622. PMID 15970906.

- ↑ "Herrin Twins". Archived from the original on 2014-06-06. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑ "Separating Twins". NOVA. Pbs.org. February 8, 2012. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑ Cai, Wenjun (July 15, 2014). "Conjoined twins to be separated". ShanghaiDaily.com. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- ↑ Wang, Hongyi (July 18, 2014). "Conjoined girls separated in surgery". Chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- ↑ Meghan Holohan (2016-10-14). "Formerly conjoined twins recovering, gaining mobility after separation".

- ↑ Meghan Holohan (2017-10-26). "Formerly conjoined twins are finally home 1 year after epic surgery".

- ↑ "Formerly conjoined twins, Erin and Abby Delaney, thriving months after separation surgery". Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. October 22, 2017. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- ↑ Rees, Gwyneth (January 23, 2019). "Two girls, one body". BBC News.

- ↑ "Conjoined twins in Blackfoot continue to beat the odds | The Spokesman-Review". www.spokesman.com. Retrieved 2020-07-27.

- ↑ "Barcroft.tv - barcroft Resources and Information". www.barcroft.tv. Retrieved 2020-07-27.

- ↑ "Second set of rare conjoined twins separated at Great Ormond Street Hospital in less than 12 months". www.gosh.nhs.uk. Retrieved 2020-07-27.

- ↑ "Separation of conjoined twins in London children's hospital 'a Moses moment'". The National. Retrieved 2020-07-27.

- ↑ Jack Guy; Sharon Braithwaite. "Twin girls, joined at the skull, successfully separated in Vatican hospital". CNN. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

- ↑ "Nigerian conjoined twins successfully separated by 78-member team in Abuja". CNN.com. January 8, 2020.

- ↑ Carpayen, Shelly (2019-11-17). "Séparée de sa soeur siamoise: Cléanne ou la joie de vivre" [Separated from her Siamese sister: Cléanne or the Joy of Living]. lexpress.mu (in French). Retrieved 2019-12-18.

- ↑ https://ionnews.mu/marie-cleanne-papillon-le-3e-bebe-siamois-miracule-au-monde-selon-son-chirurgien-28052019/.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ "Jumelles siamoises: Marie-Cléa Papillon inhumée ce mardi" [Siamese Twins: Marie-Cléa Papillon buried this Tuesday]. lexpress.mu (in French). 2019-03-26. Retrieved 2021-10-02.

- ↑ "Log into Facebook". Facebook. Retrieved 2021-12-15.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ↑ Drabble, Emily (2016-06-20). "Sarah Crossan wins the Carnegie medal with verse novel One". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

External links

![]() Media related to Conjoined twins at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Conjoined twins at Wikimedia Commons

- Types and social history of conjoined twins

- The site of the medical Saudi team responsible for numerous successful separation surgeries

- Eng and Chang - The Original Siamese Twins; The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, The North Carolina Collection Gallery

- The Human Marvels: A Historical Reference Site run by J. Tithonus Pednaud, Teratological Historian

- Cases of conjoined and incomplete twins Archived 2006-06-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Clara and Alta Rodriguez, joined at the pelvis and successfully separated in 1974 at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia by surgeons including C. Everett Koop

- National Library of Medicine: Selected Moments in the History of Conjoined Twins

- Conjoined Twins Fast Facts (also lists additional twins)

- Emedicine article (this article includes post-mortem images)

- Facts About Multiples: Conjoined Records and stats

- "The St. Benoit Twins", Scientific American, 13 July 1878, p. 24