Contact immunity

Contact immunity is the property of some vaccines, where a vaccinated individual can confer immunity upon unimmunized individuals through contact with bodily fluids or excrement.

In other words, if person “A” has been vaccinated for virus X and person “B” has not, person “B” can receive immunity to virus X just by coming into contact with person “A”. The term was coined by Romanian physician Ioan Cantacuzino.

History

The potential for contact immunity exists primarily in "live" or attenuated vaccines. Vaccination with a live, but attenuated, virus can produce immunity to more dangerous forms of the virus. These attenuated viruses produce little or no illness in most people. However, the live virus multiplies briefly, may be shed in body fluids or excrement, and can be contracted by another person. If this contact produces immunity and carries no notable risk, it benefits an additional person, and further increases the immunity of the group.

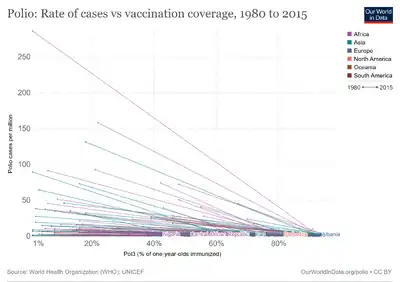

The most prominent example of contact immunity was the oral polio vaccine (OPV). This live, attenuated polio vaccine was widely used in the US between 1960 and 1990; it continues to be used in polio eradication programs in developing countries because of its low cost and ease of administration. It is popular, in part, because it is capable of contact immunity. Recently immunized children "shed" live virus in their feces for a few days after immunization. About 25 percent of people coming into contact with someone immunized with OPV gained protection from polio through this form of contact immunity.[1] Although contact immunity is an advantage of OPV, the risk of vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis—affecting 1 child per 2.4 million OPV doses administered—led the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to cease recommending its use in the US as of January 1, 2010, in favor of inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV). The CDC continues to recommend OPV over IPV for global polio eradication activities.[2]

The main drawback of live virus–based vaccines is that a few people who are vaccinated or exposed to those who have been vaccinated may develop severe disease. Those with defective immune function are the most vulnerable. In the case of OPV, an average of eight to nine adults contracted paralytic polio from contact with a recently immunized child each year. As the risk of catching polio in the Western Hemisphere diminished, the risk of contact infection with the attenuated polio virus outweighed the advantages of OPV, leading the CDC to recommend its discontinuation.[3]

Contact immunity differs from herd immunity, a different type of group protection, in which risk for unimmunized individuals is reduced if they are surrounded by immunized individuals who are unlikely to contract, harbor, or transmit the disease.

See also

References

- ↑ Offit, Paul A. (June 2010). "Polio Vaccine". The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Archived from the original on 6 September 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ↑ National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (4 February 2010). "Vaccine Information". VPD-VAC/Polio. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 18 June 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ↑ National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (6 April 2007). "Polio Vaccine Questions & Answers". Vaccines & Immunizations. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Why did CDC and ACIP change the polio vaccination schedule to an all-IPV series?. Archived from the original on 15 April 2010. Retrieved 9 October 2010.