Hemiparesis

| Hemiparesis | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Loss of motor skills on one side of body |

| Causes | Stroke |

Hemiparesis, or unilateral paresis, is weakness of one entire side of the body (hemi- means "half"). Hemiplegia is, in its most severe form, complete paralysis of half of the body. Hemiparesis and hemiplegia can be caused by different medical conditions, including congenital causes, trauma, tumors, or stroke.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Depending on the type of hemiparesis diagnosed, different bodily functions can be affected. Some effects are expected (e.g., partial paralysis of a limb on the affected side). Other impairments, though, can at first seem completely non-related to the limb weakness but are, in fact, a direct result of the damage to the affected side of the brain.[1]

Loss of motor skills

People with hemiparesis often have difficulties maintaining their balance due to limb weaknesses leading to an inability to properly shift body weight. This makes performing everyday activities such as dressing, eating, grabbing objects, or using the bathroom more difficult. Hemiparesis with origin in the lower section of the brain creates a condition known as ataxia, a loss of both gross and fine motor skills, often manifesting as staggering and stumbling. Pure Motor Hemiparesis, a form of hemiparesis characterized by sided weakness in the leg, arm, and face, is the most commonly diagnosed form of hemiparesis.[1]

Pusher syndrome

Pusher syndrome is a clinical disorder following left or right brain damage in which patients actively push their weight away from the nonhemiparetic side to the hemiparetic side. In contrast to most stroke patients, who typically prefer more weight-bearing on their nonhemiparetic side, this abnormal condition can vary in severity and leads to a loss of postural balance.[2] The lesion involved in this syndrome is thought to be in the posterior thalamus on either side, or multiple areas of the right cerebral hemisphere.[3][4]

With a diagnosis of pusher behaviour, three important variables should be seen, the most obvious of which is spontaneous body posture of a longitudinal tilt of the torso toward the paretic side of the body occurring on a regular basis and not only on occasion. The use of the nonparetic extremities to create the pathological lateral tilt of the body axis is another sign to be noted when diagnosing for pusher behaviour. This includes abduction and extension of the extremities of the non-affected side, to help in the push toward the affected (paretic) side. The third variable that is seen is that attempts of the therapist to correct the pusher posture by aiming to realign them to upright posture are resisted by the patient.[2]

In patients with acute stroke and hemiparesis, the disorder is present in 10.4% of patients.[5] Rehabilitation may take longer in patients that display pusher behaviour. The Copenhagen Stroke Study found that patients that presented with ipsilateral pushing used 3.6 weeks more to reach the same functional outcome level on the Barthel Index, than did patients without ipsilateral pushing.[5]

Pushing behavior has shown that perception of body posture in relation to gravity is altered. Patients experience their body as oriented "upright" when the body is actually tilted to the side of the brain lesion. In addition, patients seem to show no disturbed processing of visual and vestibular inputs when determining subjective visual vertical. In sitting, the push presents as a strong lateral lean toward the affected side and in standing, creates a highly unstable situation as the patient is unable to support their body weight on the weakened lower extremity. The increased risk of falls must be addressed with therapy to correct their altered perception of vertical.

Pusher syndrome is sometimes confused with and used interchangeably as the term hemispatial neglect, and some previous theories suggest that neglect leads to pusher syndrome.[2] However, another study had observed that pusher syndrome is also present in patients with left hemisphere lesions, leading to aphasia, providing a stark contrast to what was previously believed regarding hemispatial neglect, which mostly occurs with a right hemisphere lesion.[6]

Karnath[2] summarizes these two conflicting views, as they conclude that both neglect and aphasia are highly correlated with pusher syndrome possibly due to the close proximity of relevant brain structures associated with these two respective syndromes. However, the article goes on to state that it is imperative to note that both neglect and aphasia are not the underlying causes of pusher syndrome.

Physical therapists focus on motor learning strategies when treating these patients. Verbal cues, consistent feedback, practicing correct orientation and weight shifting are all effective strategies used to reduce the effects of this disorder.[7] Having a patient sit with their stronger side next to a wall and instructing them to lean towards the wall is an example of a possible treatment for pusher behaviour.[2]

A new (2003) physical therapy approach for patients with pusher syndrome suggests that the visual control of vertical upright orientation, which is undisturbed in these patients, is the central element of intervention in treatment. In sequential order, treatment is designed for patients to realize their altered perception of vertical, use visual aids for feedback about body orientation, learn the movements necessary to reach proper vertical position, and maintain vertical body position while performing other activities.[2]

Classification of pusher syndrome

Individuals who present with pusher syndrome or lateropulsion, as defined by Davies, vary in their degree and severity of this condition and therefore appropriate measures need to be implemented in order to evaluate the level of "pushing". There has been a shift towards early diagnosis and evaluation of functional status for individuals who have suffered from a stroke and presenting with pusher syndrome in order to decrease the time spent as an in-patient at hospitals and promote the return to function as early as possible.[8] Moreover, in order to assist therapists in the classification of pusher syndrome, specific scales have been developed with validity that coincides with the criteria set out by Davies’ definition of "pusher syndrome".[9] In a study by Babyar et al., an examination of such scales helped determine the relevance, practical aspects and clinimetric properties of three specific scales existing today for lateropulsion.[9] The three scales examined were the Clinical Scale of Contraversive Pushing, Modified Scale of Contraversive Pushing, and the Burke Lateropulsion Scale.[9] The results of the study show that reliability for each scale is good; moreover, the Scale of Contraversive Pushing was determined to have acceptable clinimetric properties, and the other two scales addressed more functional positions that will help therapists with clinical decisions and research.[9]

Causes

The most common cause of hemiparesis and hemiplegia is stroke. Strokes can cause a variety of movement disorders, depending on the location and severity of the lesion. Hemiplegia is common when the stroke affects the corticospinal tract. Other causes of hemiplegia include spinal cord injury, specifically Brown-Séquard syndrome, traumatic brain injury, or disease affecting the brain. A permanent brain injury that occurs during the intrauterine life, during delivery or early in life can lead to hemiplegic cerebral palsy. As a lesion that results in hemiplegia occurs in the brain or spinal cord, hemiplegic muscles display features of the upper motor neuron syndrome. Features other than weakness include decreased movement control, clonus (a series of involuntary rapid muscle contractions), spasticity, exaggerated deep tendon reflexes and decreased endurance.

The incidence of hemiplegia is much higher in premature babies than term babies. There is also a high incidence of hemiplegia during pregnancy and experts believe that this may be related to either a traumatic delivery, use of forceps or some event which causes brain injury.[10] There is tentative evidence of an association with undiagnosed celiac disease and improvement after withdrawal of gluten from the diet.[11]

Other causes of hemiplegia in adults include trauma, bleeding, brain infections and cancers. Individuals who have uncontrolled diabetes, hypertension or those who smoke have a higher chance of developing a stroke. Weakness on one side of the face may occur and may be due to a viral infection, stroke or a cancer.[12]

Common

- Vascular: cerebral hemorrhage, stroke, cerebral palsy

- Infective: encephalitis, meningitis, brain abscess, cerebral palsy, spinal epidural abscess

- Neoplastic: glioma, meningioma, brain tumors, spinal cord tumors

- Demyelination: multiple sclerosis, disseminated sclerosis, ADEM, neuromyelitis optica

- Traumatic: cerebral lacerations, subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma, cerebral palsy, vertebral compression fracture

- Iatrogenic: local anaesthetic injections given intra-arterially rapidly, instead of given in a nerve branch.

- Ictal: seizure, Todd's paralysis

- Congenital: cerebral palsy, Neonatal-Onset Multisystem Inflammatory Disease (NOMID)

- Degenerative: ALS, corticobasal degeneration

- Parasomnia: sleep paralysis[13]

Mechanism

Movement of the body is primarily controlled by the pyramidal (or corticospinal) tract, a pathway of neurons that begins in the motor areas of the brain, projects down through the internal capsule, continues through the brainstem, decussates (or cross midline) at the lower medulla, then travels down the spinal cord into the motor neurons that control each muscle. In addition to this main pathway, there are smaller contributing pathways (including the anterior corticospinal tract), some portions of which do not cross the midline.

Because of this anatomy, injuries to the pyramidal tract above the medulla generally cause contralateral hemiparesis (weakness on the opposite side as the injury). Injuries at the lower medulla, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves result in ipsilateral hemiparesis.

In a few cases, lesions above the medulla have resulted in ipsilateral hemiparesis:

- In several reported cases, patients with hemiparesis from an old contralateral brain injury subsequently experienced worsening of their hemiparesis when hit with a second stroke in the ipsilateral brain.[14][15][16] The authors hypothesize that brain reorganization after the initial injury led to more reliance on uncrossed motor pathways, and when these compensatory pathways were damaged by a second stroke, motor function worsened further.

- A case report describes a patient with a congenitally uncrossed pyramidal tract, who developed right-sided hemiparesis after a hemorrhage in the right brain.[17]

Diagnosis

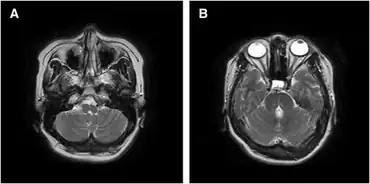

Hemiplegia is identified by clinical examination by a health professional, such as a physiotherapist or doctor. Radiological studies like a CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain should be used to confirm injury in the brain and spinal cord, but alone cannot be used to identify movement disorders. Individuals who develop seizures may undergo tests to determine where the focus of excess electrical activity is.[18]

Hemiplegia patients usually show a characteristic gait. The leg on the affected side is extended and internally rotated and is swung in a wide, lateral arc rather than lifted in order to move it forward. The upper limb on the same side is also adducted at the shoulder, flexed at the elbow, and pronated at the wrist with the thumb tucked into the palm and the fingers curled around it.[19]

Assessment tools

There are a variety of standardized assessment scales available to physiotherapists and other health care professionals for use in the ongoing evaluation of the status of a patient’s hemiplegia. The use of standardized assessment scales may help physiotherapists and other health care professionals during the course of their treatment plant to:

- Prioritize treatment interventions based on specific identifiable motor and sensory deficits

- Create appropriate short- and long-term goals for treatment based on the outcome of the scales, their professional expertise and the desires of the patient

- Evaluate the potential burden of care and monitor any changes based on either improving or declining scores

Some of the most commonly used scales in the assessment of hemiplegia are:

The FMA is often used as a measure of functional or physical impairment following a cerebrovascular accident (CVA).[21] It measures sensory and motor impairment of the upper and lower extremities, balance in several positions, range of motion, and pain. This test is a reliable and valid measure in measuring post-stroke impairments related to stroke recovery. A lower score in each component of the test indicates higher impairment and a lower functional level for that area. The maximum score for each component is 66 for the upper extremities, 34 for the lower extremities, and 14 for balance. [22] Administration of the FMA should be done after reviewing a training manual.[23]

- The Chedoke-McMaster Stroke Assessment (CMSA)[24]

This test is a reliable measure of two separate components evaluating both motor impairment and disability.[25] The disability component assesses any changes in physical function including gross motor function and walking ability. The disability inventory can have a maximum score of 100 with 70 from the gross motor index and 30 from the walking index. Each task in this inventory has a maximum score of seven except for the 2 minute walk test which is out of two. The impairment component of the test evaluates the upper and lower extremities, postural control and pain. The impairment inventory focuses on the seven stages of recovery from stroke from flaccid paralysis to normal motor functioning. A training workshop is recommended if the measure is being utilized for the purpose of data collection.[26]

- The Stroke Rehabilitation Assessment of Movement (STREAM)[27]

The STREAM consists of 30 test items involving upper-limb movements, lower-limb movements, and basic mobility items. It is a clinical measure of voluntary movements and general mobility (rolling, bridging, sit-to-stand, standing, stepping, walking and stairs) following a stroke. The voluntary movement part of the assessment is measured using a 3-point ordinal scale (unable to perform, partial performance, and complete performance) and the mobility part of the assessment uses a 4-point ordinal scale (unable, partial, complete with aid, complete no aid). The maximum score one can receive on the STREAM is a 70 (20 for each limb score and 30 for mobility score). The higher the score, the better movement and mobility is available for the individual being scored.[28]

Treatment

Treatment for hemiparesis is the same treatment given to those recovering from strokes or brain injuries.[1] Health care professionals such as physical therapists and occupational therapists play a large role in assisting these patients in their recovery. Treatment is focused on improving sensation and motor abilities, allowing the patient to better manage their activities of daily living. Some strategies used for treatment include promoting the use of the hemiparetic limb during functional tasks, maintaining range of motion, and using neuromuscular electrical stimulation to decrease spasticity and increase awareness of the limb.

At the more advanced level, using constraint-induced movement therapy will encourage overall function and use of the affected limb.[29] Mirror Therapy (MT) has also been used early in stroke rehabilitation and involves using the unaffected limb to stimulate motor function of the hemiparetic limb. Results from a study on patients with severe hemiparesis concluded that MT was successful in improving motor and sensory function of the distal hemiparetic upper limb.[30] Active participation is critical to the motor learning and recovery process, therefore it’s important to keep these individuals motivated so they can make continual improvements.[31]

Also speech pathologists work to increase function for people with hemiparesis.

Treatment should be based on assessment by the relevant health professionals, including physiotherapists, doctors and occupational therapists. Muscles with severe motor impairment including weakness need these therapists to assist them with specific exercise, and are likely to require help to do this.[32]

Medication

Drugs can be used to treat issues related to the Upper Motor Neuron Syndrome. Drugs like Librium or Valium could be used as a relaxant. Drugs are also given to individuals who have recurrent seizures, which may be a separate but related problem after brain injury.[33] Intra-muscular injection of Botulinum toxin A is used to treat spasticity that is associated with hemiparesis both in cerebral palsy children and stroke in adults. It can be injected into a muscle or more commonly muscle groups of the upper or lower extremities. Botulinum toxin A induces temporary muscle paralysis or relaxation. The main goal of Botulinum toxin A is to maintain the range of motion of affected joints and to prevent the occurrence of fixed joint contractures or stiffness.[34][35]

Surgery

Surgery may be used if the individual develops a secondary issue of contracture, from a severe imbalance of muscle activity. In such cases the surgeon may cut the ligaments and relieve joint contractures. Individuals who are unable to swallow may have a tube inserted into the stomach. This allows food to be given directly into the stomach. The food is in liquid form and instilled at low rates. Some individuals with hemiplegia will benefit from some type of prosthetic device. There are many types of braces and splints available to stabilize a joint, assist with walking and keep the upper body erect.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation is the main treatment of individuals with hemiplegia. In all cases, the major aim of rehabilitation is to regain maximum function and quality of life. Both physical and occupational therapy can significantly improve the quality of life.

Physical therapy

Physical therapy (PT) can help improve muscle strength & coordination, mobility (such as standing and walking), and other physical function using different sensorimotor techniques.[36] Physiotherapists can also help reduce shoulder pain by maintaining shoulder range of motion, as well as using Functional electrical stimulation.[37] Supportive devices, such as braces or slings, can be used to help prevent or treat shoulder subluxation[38] in the hopes to minimize disability and pain. Although many individuals suffering from stroke experience both shoulder pain and shoulder subluxation, the two are mutually exclusive.[39] A treatment method that can be implemented with the goal of helping to regain motor function in the affected limb is constraint-induced movement therapy. This consists of constraining the unaffected limb, forcing the affected limb to accomplish tasks of daily living.[40]

Occupational therapy

Occupational therapists may specifically help with hemiplegia with tasks such as improving hand function, strengthening hand, shoulder and torso, and participating in activities of daily living (ADLs), such as eating and dressing. Therapists may also recommend a hand splint for active use or for stretching at night. Some therapists actually make the splint; others may measure your child’s hand and order a splint. OTs educate patients and family on compensatory techniques to continue participating in daily living, fostering independence for the individual - which may include, environmental modification, use of adaptive equipment, sensory integration, etc.

Orthotic Intervention

Orthotic devices are one type of intervention for relieving symptoms of hemiparesis. Commonly called braces, orthotics range from 'off the shelf' to custom fabricated solutions, but their main goal is alike, to supplement diminished or missing muscle function and joint laxity. A wide range of orthotic treatment can be designed by a Certified Orthotist (C.O.) or Certified Prosthetist Orthotist (C.P.O). Orthotics may be made of metal, plastic, or composite material (such as fiberglass, dyneema (HMWPE,) carbon fiber; etc) and design may be changed to address many different conditions.

and range from the level of ankle to the hip depending on the level of intervention, support, or control needed.,

Prognosis

Hemiplegia is not a progressive disorder, except in progressive conditions like a growing brain tumour. Once the injury has occurred, the symptoms should not worsen. However, because of lack of mobility, other complications can occur. Complications may include muscle and joint stiffness, loss of aerobic fitness, muscle spasms, bed sores, pressure ulcers and blood clots.[41]

Sudden recovery from hemiplegia is very rare. Many of the individuals will have limited recovery, but the majority will improve from intensive, specialised rehabilitation. Potential to progress may differ in cerebral palsy, compared to adult acquired brain injury. It is vital to integrate the hemiplegic child into society and encourage them in their daily living activities. With time, some individuals may make remarkable progress.[41]

Popular culture

- In Barbara Kingsolver's novel, The Poisonwood Bible, the character Adah is incorrectly diagnosed, in childhood, as having hemiplegia.[42][43]

- Rock band HAERTS released an EP called Hemiplegia via Columbia Records in 2013.[44]

- In the 1994 Jodie Foster film Nell, the title character portrayed by Foster has developed her own language (idioglossia), developed in part due to the distinct speech patterns of her mother, caused by her hemiplegia due to a stroke.

- In the anime series Mobile Suit Gundam: Iron-Blooded Orphans, the protagonist Mikazuki Augus is paralyzed in the entire right half of his body after a fierce battle with the Mobile Armor Hashmal. In order to defeat the Mobile Armor, he was forced to deactivate the safety limiter on his Gundam's neural interface and overloading the connection between him and the Mobile Suit for the necessary power.

See also

- Alternating hemiplegia

- Brunnstrom Approach

- Hemiplegic migraine

- Laryngeal paralysis

- Paraplegia

- Paresis

References

- 1 2 3 4 Detailed article about hemiparesis Archived 2022-02-02 at the Wayback Machine at Disabled-World.com

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Karnath HO, Broetz D (December 2003). "Understanding and treating "pusher syndrome"". Physical Therapy. 83 (12): 1119–25. doi:10.1093/ptj/83.12.1119. PMID 14640870. Archived from the original on 2013-04-15.

- ↑ Karnath HO, Ferber S, Dichgans J (November 2000). "The origin of contraversive pushing: evidence for a second graviceptive system in humans". Neurology. 55 (9): 1298–304. doi:10.1212/wnl.55.9.1298. PMID 11087771. S2CID 19399616.

- ↑ Karnath HO, Ferber S, Dichgans J (December 2000). "The neural representation of postural control in humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (25): 13931–6. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9713931K. doi:10.1073/pnas.240279997. PMC 17678. PMID 11087818.

- 1 2 Pedersen PM, Wandel A, Jørgensen HS, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS (January 1996). "Ipsilateral pushing in stroke: incidence, relation to neuropsychological symptoms, and impact on rehabilitation. The Copenhagen Stroke Study". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 77 (1): 25–8. doi:10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90215-4. PMID 8554469.

- ↑ Davies PM (1985). Steps to follow: A guide to the treatment of adult hemiplegia : Based on the concept of K. and B. Bobath. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- ↑ O'Sullivan S (2007). "Ch. 12: Stroke". In O'Sullivan S, Schmitz T (eds.). Physical Rehabilitation (5th ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis. pp. 705–769.

- ↑ Lagerqvist, J.; Skargren, E. (2006). "Pusher syndrome: reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change of a classification instrument". Advances in Physiotherapy. 8 (4): 154–160. doi:10.1080/14038190600806596. S2CID 145015737.

- 1 2 3 4 Babyar SR, Peterson MG, Bohannon R, Pérennou D, Reding M (July 2009). "Clinical examination tools for lateropulsion or pusher syndrome following stroke: a systematic review of the literature". Clinical Rehabilitation. 23 (7): 639–50. doi:10.1177/0269215509104172. PMID 19403555. S2CID 40016612.

- ↑ "hemiplegia in children". Children's Hemiplegia and Stroke Association (CHASA). Archived from the original on February 4, 2012.

- ↑ Shapiro M, Blanco DA (February 2017). "Neurological Complications of Gastrointestinal Disease". Seminars in Pediatric Neurology (Review). 24 (1): 43–53. doi:10.1016/j.spen.2017.02.001. PMID 28779865.

- ↑ "What is hemiplegia? | HemiHelp: for children and young people with hemiplegia (hemiparesis)". HemiHelp. Archived from the original on 2013-03-05. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- ↑ Martin L (2009). "I was awake -- and could not move!". Lakesidepress.com. Archived from the original on 2017-05-13. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

Sleep paralysis, parasomnia, sleep apnea, sleep eat, parasomnias, paresthesias, dysesthesias, obstructive sleep apnea, REM, Stage 1, Sinemet narcolepsy, insomnia, cataplexy, benzodiazepines, opioids, sleepiness, sleep walking, daytime sleepiness, upper airway, CPAP, hypoxemia, UVVP, uvula, Somnoplasty, obesity, airway obstruction, EEG, electroencephalogram, Klonopine, night terrors, bruxism, parasomnias, EMG, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, BiPAP, sleep efficiency

- ↑ Ago T, Kitazono T, Ooboshi H, Takada J, Yoshiura T, Mihara F, et al. (August 2003). "Deterioration of pre-existing hemiparesis brought about by subsequent ipsilateral lacunar infarction". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 74 (8): 1152–3. doi:10.1136/jnnp.74.8.1152. PMC 1738578. PMID 12876260.

- ↑ Song YM, Lee JY, Park JM, Yoon BW, Roh JK (May 2005). "Ipsilateral hemiparesis caused by a corona radiata infarct after a previous stroke on the opposite side". Archives of Neurology. 62 (5): 809–11. doi:10.1001/archneur.62.5.809. PMID 15883270.

- ↑ Yamamoto S, Takasawa M, Kajiyama K, Baron JC, Yamaguchi T (2007). "Deterioration of hemiparesis after recurrent stroke in the unaffected hemisphere: Three further cases with possible interpretation". Cerebrovascular Diseases. 23 (1): 35–9. doi:10.1159/000095756. PMID 16968984. S2CID 40273792.

- ↑ Terakawa H, Abe K, Nakamura M, Okazaki T, Obashi J, Yanagihara T (May 2000). "Ipsilateral hemiparesis after putaminal hemorrhage due to uncrossed pyramidal tract" (PDF). Neurology. 54 (9): 1801–5. doi:10.1212/WNL.54.9.1801. PMID 10802787. S2CID 15086685. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-08. Retrieved 2022-01-07.

- ↑ "Spastic Hemiplegia : Cerebral Palsy". OriginsOfCerebralPalsy.com. Archived from the original on 2018-01-26. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- ↑ "Gait Abnormalities". The Stanford 25. Archived from the original on October 11, 2010.

- ↑ Fugl-Meyer AR, Jääskö L, Leyman I, Olsson S, Steglind S (1975). "The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. a method for evaluation of physical performance". Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 7 (1): 13–31. PMID 1135616.

- ↑ Sullivan KJ, Tilson JK, Cen SY, Rose DK, Hershberg J, Correa A, et al. (February 2011). "Fugl-Meyer assessment of sensorimotor function after stroke: standardized training procedure for clinical practice and clinical trials". Stroke. 42 (2): 427–32. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.592766. PMID 21164120.

- ↑ Sullivan SB (2007). "Stroke". In O'Sullivan SB, Schmitz TJ (eds.). Physical Rehabilitation (5th ed.). Philadelphia PA: F.A. Davis.

- ↑ "Fugl-Meyer Assessment of Motor Recovery after". Rehab Measures. Archived from the original on 2016-09-24. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- ↑ Gowland C, Stratford P, Ward M, Moreland J, Torresin W, Van Hullenaar S, et al. (January 1993). "Measuring physical impairment and disability with the Chedoke-McMaster Stroke Assessment". Stroke. 24 (1): 58–63. doi:10.1161/01.STR.24.1.58. PMID 8418551.

- ↑ Valach L, Signer S, Hartmeier A, Hofer K, Steck GC (June 2003). "Chedoke-McMaster stroke assessment and modified Barthel Index self-assessment in patients with vascular brain damage". International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 26 (2): 93–9. doi:10.1097/00004356-200306000-00003. PMID 12799602.

- ↑ "Chedoke-McMaster Stroke Assessment Measure". Rehab Measures. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- ↑ Daley K, Mayo N, Wood-Dauphinée S (January 1999). "Reliability of scores on the Stroke Rehabilitation Assessment of Movement (STREAM) measure". Physical Therapy. 79 (1): 8–19, quiz 20–3. doi:10.1093/ptj/79.1.8. PMID 9920188. Archived from the original on 2013-04-15. Retrieved 2022-01-07.

- ↑ O'sullivan S, Schmitz T (2007). Physical Rehabilitation (5th ed.). Philadelphia PA: F.A. Davis. p. 736.

- ↑ Sterr A, Freivogel S (September 2003). "Motor-improvement following intensive training in low-functioning chronic hemiparesis". Neurology. 61 (6): 842–4. doi:10.1212/wnl.61.6.842. PMID 14504336. S2CID 43563527.

- ↑ Dohle C, Püllen J, Nakaten A, Küst J, Rietz C, Karbe H (2009). "Mirror therapy promotes recovery from severe hemiparesis: a randomized controlled trial". Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 23 (3): 209–17. doi:10.1177/1545968308324786. PMID 19074686. S2CID 14252958. Archived from the original on 2022-02-02. Retrieved 2022-01-07.

- ↑ Stroke in Physical Rehabilitation 2007, p. 746

- ↑ Patten C, Lexell J, Brown HE (May 2004). "Weakness and strength training in persons with poststroke hemiplegia: rationale, method, and efficacy". Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 41 (3A): 293–312. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2004.03.0293. PMID 15543447. S2CID 563507. Archived from the original on 2022-02-02. Retrieved 2022-01-07.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-04-20. Retrieved 2014-10-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Farag SM, Mohammed MO, El-Sobky TA, ElKadery NA, ElZohiery AK (March 2020). "Botulinum Toxin A Injection in Treatment of Upper Limb Spasticity in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials". JBJS Reviews. 8 (3): e0119. doi:10.2106/JBJS.RVW.19.00119. PMC 7161716. PMID 32224633.

- ↑ Blumetti FC, Belloti JC, Tamaoki MJ, Pinto JA (October 2019). "Botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of lower limb spasticity in children with cerebral palsy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD001408. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001408.pub2. PMC 6779591. PMID 31591703.

- ↑ Barreca S, Wolf SL, Fasoli S, Bohannon R (December 2003). "Treatment interventions for the paretic upper limb of stroke survivors: a critical review". Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 17 (4): 220–6. doi:10.1177/0888439003259415. PMID 14677218. S2CID 23055506.

- ↑ Price CI, Pandyan AD (February 2001). "Electrical stimulation for preventing and treating post-stroke shoulder pain: a systematic Cochrane review". Clinical Rehabilitation. 15 (1): 5–19. doi:10.1191/026921501670667822. PMID 11237161. S2CID 1792159. Archived from the original on 2022-02-02. Retrieved 2022-01-07.

- ↑ Ada L, Foongchomcheay A, Canning C (January 2005). Ada L (ed.). "Supportive devices for preventing and treating subluxation of the shoulder after stroke". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD003863. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003863.pub2. PMC 6984447. PMID 15674917. S2CID 10451803.

- ↑ Zorowitz RD, Hughes MB, Idank D, Ikai T, Johnston MV (March 1996). "Shoulder pain and subluxation after stroke: correlation or coincidence?". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 50 (3): 194–201. doi:10.5014/ajot.50.3.194. PMID 8822242.

- ↑ Wittenberg GF, Schaechter JD (December 2009). "The neural basis of constraint-induced movement therapy". Current Opinion in Neurology. 22 (6): 582–8. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283320229. PMID 19741529. S2CID 16050784.

- 1 2 "Hemiplegia (Hemiparalysis)". Healthopedia.com. 2009-04-06. Archived from the original on 2012-11-24. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- ↑ "Kingsolver, Barbara : The Poisonwood Bible". Litmed.med.nyu.edu. 2000-05-17. Archived from the original on 2013-06-29. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- ↑ "The Poisonwood Bible Barbara Kingsolver Study Guide, Lesson Plan & more". eNotes.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-21. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- ↑ "HAERTS Announce Debut EP Hemiplegia, Out 9/17 on Columbia Records". broadwayworld.com. 2013-08-08. Archived from the original on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2013-10-19.

External links

| Classification |

|---|