Neurofeedback

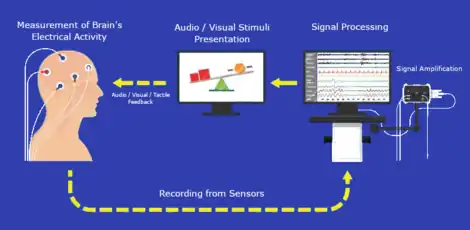

Neurofeedback (NFB), also called neurotherapy, is a type of biofeedback that presents real-time feedback from brain activity in order to reinforce healthy brain function through operant conditioning. Typically, electrical activity from the brain is collected via sensors placed on the scalp using electroencephalography (EEG), with feedback presented using video displays or sound. There is significant evidence supporting neurotherapy for generalized treatment of mental disorders,[1] [2] and it has been practiced over four decades, although never gaining prominence in the medical mainstream. NFB is relatively non-invasive and is administered as a long-term treatment option, typically taking a month to complete.

Several neurofeedback protocols exist, with additional benefit from use of quantitative electroencephalography (QEEG) or functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to localize and personalize treatment.[3][4] Related technologies include functional near-infrared spectroscopy-mediated (fNIRS) neurofeedback, hemoencephalography biofeedback (HEG) and fMRI biofeedback.

Applications

ADHD

Since the first reports of neurofeedback treatment in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in 1976, many studies have investigated the effects of neurofeedback on different symptoms of ADHD such as inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity. Recent investigation into the effectiveness of neurofeedback for ADHD has found neurofeedback to have durable effects following treatment,[5][6] although prior work has contradicted this conclusion.[7] Standard neurofeedback protocols for ADHD include theta/beta, SMR and slow cortical potentials are well investigated and have demonstrated specificity.[8]

Depressive and anxiety disorders

Neurofeedback training, particularly localized neurofeedback training, has been found to be therapeutic for patients for depression and self-regulation.[3][9] Individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) also have been found to benefit from neurofeedback, including children with developmental trauma.[10][11][12]

Traumatic brain injury and stroke

Neurofeedback has been used to treat traumatic brain injury (TBI) in military and civilian populations.[13][14] Neurofeedback has been also found to be generally positive for stroke recovery, with improvements found in motor function and behavior comparable with conventional occupational therapy.[15][16][17]

Epilepsy

Neurofeedback has been found to be a viable alternative for patients who did not find benefit from other medical treatment. The most common protocol for seizure control was sensorimotor rhythm (SMR), which was found to significantly reduce weekly seizures.[18][19]

Performance enhancement

The applications of neurofeedback to enhance performance extend to the arts in fields such as music, dance, and acting. A study with conservatoire musicians found that alpha-theta training benefitted the three music domains of musicality, communication, and technique.[20] Historically, alpha-theta training, a form of neurofeedback, was created to assist creativity by inducing hypnagogia, a "borderline waking state associated with creative insights", through facilitation of neural connectivity.[21] Alpha-theta training has also been shown to improve novice singing in children. Alpha-theta neurofeedback, in conjunction with heart rate variability training, a form of biofeedback, has also produced benefits in dance by enhancing performance in competitive ballroom dancing and increasing cognitive creativity in contemporary dancers. Additionally, neurofeedback has also been shown to instil a superior flow state in actors, possibly due to greater immersion while performing.[21]

However, randomized control trials have found that neurofeedback training (using either sensorimotor rhythm or theta/beta ratio training) did not enhance performance on attention-related tasks or creative tasks.[22] It has been suggested that claims made by proponents of alpha wave neurofeedback training techniques have yet to be validated by randomized, double-blind, controlled studies,[23] a view which even some supporters of alpha neurofeedback training have also expressed.[24]

Neurofeedback has been used to improve athletic psychomotor and self-regulation ability.[25] Sensorimotor rhythm neurofeedback training of accuracy has been used in top-level sports, especially in target-based sports (e.g. golf).[26]

History

In 1924, the German psychiatrist Hans Berger connected a couple of electrodes (small round discs of metal) to a patient's scalp and detected a small current by using a ballistic galvanometer. During the years 1929–1938 he published 14 reports about his studies of EEGs, and much of our modern knowledge of the subject, especially in the middle frequencies, is due to his research.[27] Berger analyzed EEGs qualitatively, but in 1932 G. Dietsch applied Fourier analysis to seven records of EEG and became the first researcher of what later is called QEEG (quantitative EEG).[27]

The first study to demonstrate neurofeedback was reported by Joe Kamiya in 1962.[28][29] Kamiya's experiment had two parts. In the first part, a subject was asked to keep his eyes closed and when a tone sounded to say whether he thought he was in alpha. He was then told whether he was correct or wrong. Initially the subject would get about fifty percent correct, but some subjects would eventually develop the ability to better distinguish between states.[30] Many could then produce alpha and non-alpha states at will. In the second part of the study, a tone was sounded whenever alpha was present, and subjects were asked to increase the percentage time the tone was on. Most participants were able increase their percent time spent in alpha within about four training sessions.[29] Maintaining the alpha state was found to be associated with relaxation, a sense of "letting go", and pleasant affect.[31] High alpha amplitude had been seen in advanced meditators,[32][33][34] combined with an emerging counter-cultural interest in altered states of consciousness, led to significant public interest in alpha training as an alternative to psychedelic drugs.[35] Several optimistic studies replicated Kamiya’s findings and suggested alpha training could be useful for treating stress and anxiety.[36][37][38] However, other studies found that alpha was not reliably associated with calm and pleasant mental states, while eyes-closed alpha never increased above the resting baseline.[39] Hardt and Kamiya (1976) argued that the replication failures were an artifact of an incorrect method of measuring alpha,[40] and future studies continued to demonstrate learning of alpha based on feedback.[41][42]

In the late sixties and early seventies, Barbara Brown, one of the most effective popularizers of Biofeedback, wrote several books on biofeedback, making the public much more aware of the technology. The books included New Mind New Body, with a foreword from Hugh Downs, and Stress and the Art of Biofeedback. Brown took a creative approach to neurofeedback, linking brainwave self-regulation to a switching relay which turned on an electric train.

The work of Barry Sterman, Joel F. Lubar and others has been relevant on the study of beta training, involving the role of sensorimotor rhythmic EEG activity.[43] This training has been used in the treatment of epilepsy,[44][45] attention deficit disorder and hyperactive disorder.[46] The sensorimotor rhythm (SMR) is rhythmic activity between 12 and 16 hertz that can be recorded from an area near the sensorimotor cortex. SMR is found in waking states and is very similar if not identical to the sleep spindles that are recorded in the second stage of sleep.

For example, Sterman has shown that both monkeys and cats who had undergone SMR training had elevated thresholds for the convulsant chemical monomethylhydrazine. These studies indicate that SMR may be associated with an inhibitory process in the motor system.[45]

In the 2000s, neurofeedback took a new approach in taking a look at deep states.[47] Alpha-theta training has been tried with patients with alcoholism,[48] other addictions as well as anxiety.[48] This low frequency training differs greatly from the high frequency beta and SMR training that has been practiced for over thirty years and is reminiscent of the original alpha training of Elmer Green and Joe Kamiya.[48] Beta and SMR training can be considered a more directly physiological approach, strengthening sensorimotor inhibition in the cortex and inhibiting alpha patterns, which slow metabolism. Alpha-theta training, however, derives from the psychotherapeutic model and involves accessing of painful or repressed memories through the alpha-theta state.[49] The alpha-theta state is a term that comes from the representation on the EEG.

A recent development in the field is a conceptual approach called the Coordinated Allocation of Resource Model (CAR) of brain functioning which states that specific cognitive abilities are a function of specific electrophysiological variables which can overlap across different cognitive tasks.[50] The activation database guided EEG biofeedback approach initially involves evaluating the subject on a number of academically relevant cognitive tasks and compares the subject's values on the QEEG measures to a normative database, in particular on the variables that are related to success at that task.

Organizations

The Society of Applied Neuroscience (SAN) is an EU-based nonprofit membership organization for the advancement of neuroscientific knowledge and development of innovative applications for optimizing brain functioning (such as neurofeedback with EEG, fMRI, NIRS). The International Society for Neurofeedback & Research (ISNR) is a membership organization aimed at supporting scientific research in applied neurosciences, promoting education in the field of neurofeedback.

The Foundation for Neurofeedback and Neuromodulation Research is a non-profit organization that, through donations, provides grants for student research. The FNNR also issues awards for professionals and publishes books related to neurofeedback.

The Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback (AAPB) is a non-profit scientific and professional society for biofeedback and neurofeedback. The International Society for Neurofeedback and Research (ISNR) is a non-profit scientific and professional society for neurofeedback.[51] The Biofeedback Federation of Europe (BFE) sponsors international education, training, and research activities in biofeedback and neurofeedback.

Certification

The Biofeedback Certification International Alliance (formerly the Biofeedback Certification Institute of America) is a non-profit organization that is a member of the Institute for Credentialing Excellence (ICE). BCIA certifies individuals who meet education and training standards in biofeedback and neurofeedback and progressively recertifies those who satisfy continuing education requirements. BCIA offers biofeedback certification, neurofeedback (also called EEG biofeedback) certification, and pelvic muscle dysfunction biofeedback certification. BCIA certification has been endorsed by the Mayo Clinic,[52] the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback (AAPB), the International Society for Neurofeedback and Research (ISNR), and the Washington State Legislature.[53]

The BCIA didactic education requirement includes a 36-hour course from a regionally accredited academic institution or a BCIA-approved training program that covers the complete Neurofeedback Blueprint of Knowledge and study of human anatomy and physiology. Applicants must also pass a written exam, complete 25 hours of mentoring, 10 case reviews, perform 100 hours of client sessions, and conduct 10 hours of personal NF. The Neurofeedback Blueprint of Knowledge areas include: I. Orientation to Neurofeedback, II. Basic Neurophysiology and Neuroanatomy, III. Instrumentation and Electronics, IV. Research, V. Psychopharmalogical Considerations, VI. Treatment Planning, and VII. Professional Conduct.[54]

Applicants may demonstrate their knowledge of human anatomy and physiology by completing a course in biological psychology, human anatomy, human biology, human physiology, or neuroscience provided by a regionally accredited academic institution or a BCIA-approved training program or by successfully completing an Anatomy and Physiology exam covering the organization of the human body and its systems.

Applicants must also document practical skills training that includes 25 contact hours supervised by a BCIA-approved mentor designed to teach them how to apply clinical biofeedback skills through self-regulation training, 100 patient/client sessions, and case conference presentations. Distance learning allows applicants to complete didactic course work over the internet. Distance mentoring trains candidates from their residence or office.[55] They must recertify every four years, complete 55 hours of continuing education (30 hours for Senior Fellows) during each review period or complete the written exam, and attest that their license/credential (or their supervisor's license/credential) has not been suspended, investigated, or revoked.[56]

Neuroplasticity

In 2010, a study provided some evidence of neuroplastic changes occurring after brainwave training. Half an hour of voluntary control of brain rhythms led in this study to a lasting shift in cortical excitability and intracortical function.[57] The authors observed that the cortical response to transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) was significantly enhanced after neurofeedback, persisted for at least 20-minutes, and was correlated with an EEG time-course indicative of activity-dependent plasticity[57]

Criticism of the medical application

The effectiveness of the medical treatment of psychiatric disorders using EEG neurofeedback was called into question by Thibault et al (2015, 2017). [58] [59] However, the validity of the research by Thibault et al (2017) was later called into question (Pigott et al, 2018).

A double-blinded, sham-controlled study of neurofeedback as a treatment for insomnia (Schabus et al, 2017) found that neurofeedback did not beat placebo.[60]

Over 3,000 scientific articles have been published on EEG neurofeedback since 1968, and in 2019, the FDA permitted marketing of the first neurofeedback medical device for treatment of ADHD.[61]

See also

- Brainwave synchronization

- Decoded neurofeedback

- Comparison of neurofeedback software

- Mind machine

References

- ↑ "Isnr-comprehensive-bibliography". ISNR. 2019-07-11. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ↑ Omejc, N., Rojc, B., Battaglini, P. P., & Marusic, U. (2019). Review of the therapeutic neurofeedback method using electroencephalography: EEG Neurofeedback. Bosnian journal of basic medical sciences, 19(3), 213–220. https://doi.org/10.17305/bjbms.2018.3785

- 1 2 Mehler DM, Sokunbi MO, Habes I, Barawi K, Subramanian L, Range M, et al. (December 2018). "Targeting the affective brain-a randomized controlled trial of real-time fMRI neurofeedback in patients with depression". Neuropsychopharmacology. 43 (13): 2578–2585. doi:10.1038/s41386-018-0126-5. PMC 6186421. PMID 29967368.

- ↑ Arns M, Drinkenburg W, Leon Kenemans J (September 2012). "The effects of QEEG-informed neurofeedback in ADHD: an open-label pilot study". Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 37 (3): 171–80. doi:10.1007/s10484-012-9191-4. PMC 3419351. PMID 22446998.

- ↑ Van Doren J, Arns M, Heinrich H, Vollebregt MA, Strehl U, K Loo S (March 2019). "Sustained effects of neurofeedback in ADHD: a systematic review and meta-analysis". European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 28 (3): 293–305. doi:10.1007/s00787-018-1121-4. PMC 6404655. PMID 29445867.

- ↑ Moreno-García I, Meneres-Sancho S, Camacho-Vara de Rey C, Servera M (February 2019). "A Randomized Controlled Trial to Examine the Posttreatment Efficacy of Neurofeedback, Behavior Therapy, and Pharmacology on ADHD Measures". Journal of Attention Disorders. 23 (4): 374–383. doi:10.1177/1087054717693371. PMID 29254414. S2CID 39049130.

- ↑ Lansbergen MM, van Dongen-Boomsma M, Buitelaar JK, Slaats-Willemse D (February 2011). "ADHD and EEG-neurofeedback: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled feasibility study". Journal of Neural Transmission. 118 (2): 275–84. doi:10.1007/s00702-010-0524-2. PMC 3051071. PMID 21165661.

- ↑ Arns M, Heinrich H, Strehl U (January 2014). "Evaluation of neurofeedback in ADHD: the long and winding road". Biological Psychology. 95: 108–15. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.11.013. PMID 24321363. S2CID 22044367.

- ↑ Linden DE (March 2014). "Neurofeedback and networks of depression". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 16 (1): 103–12. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.1/dlinden. PMC 3984886. PMID 24733975.

- ↑ Gapen M, van der Kolk BA, Hamlin E, Hirshberg L, Suvak M, Spinazzola J (September 2016). "A Pilot Study of Neurofeedback for Chronic PTSD". Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 41 (3): 251–61. doi:10.1007/s10484-015-9326-5. PMID 26782083. S2CID 14234363.

- ↑ Rogel A, Loomis AM, Hamlin E, Hodgdon H, Spinazzola J, van der Kolk B (November 2020). "The impact of neurofeedback training on children with developmental trauma: A randomized controlled study". Psychological Trauma : Theory, Research, Practice and Policy. 12 (8): 918–929. doi:10.1037/tra0000648. PMID 32658503.

- ↑ Steingrimsson S, Bilonic G, Ekelund AC, Larson T, Stadig I, Svensson M, et al. (January 2020). "Electroencephalography-based neurofeedback as treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis". European Psychiatry. 63 (1): e7. doi:10.1192/j.eurpsy.2019.7. PMC 8057448. PMID 32093790.

- ↑ May G, Benson R, Balon R, Boutros N (November 2013). "Neurofeedback and traumatic brain injury: a literature review". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 25 (4): 289–96. PMID 24199220.

- ↑ Gray SN (August 2017). "An Overview of the Use of Neurofeedback Biofeedback for the Treatment of Symptoms of Traumatic Brain Injury in Military and Civilian Populations". Medical Acupuncture. 29 (4): 215–219. doi:10.1089/acu.2017.1220. PMC 5580369. PMID 28874922.

- ↑ Wang T, Mantini D, Gillebert CR (October 2018). "The potential of real-time fMRI neurofeedback for stroke rehabilitation: A systematic review". Cortex; A Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior. 107: 148–165. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2017.09.006. PMC 6182108. PMID 28992948.

- ↑ Mihara M, Fujimoto H, Hattori N, Otomune H, Kajiyama Y, Konaka K, et al. (April 2021). "Effect of Neurofeedback Facilitation on Post-stroke Gait and Balance Recovery: A Randomized Controlled Trial". Neurology. 96 (21): e2587–e2598. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000011989. PMC 8205450. PMID 33879597.

- ↑ Rayegani SM, Raeissadat SA, Sedighipour L, Rezazadeh IM, Bahrami MH, Eliaspour D, Khosrawi S (2014-03-01). "Effect of neurofeedback and electromyographic-biofeedback therapy on improving hand function in stroke patients". Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. 21 (2): 137–51. doi:10.1310/tsr2102-137. PMID 24710974. S2CID 24528611.

- ↑ Sterman MB, Egner T (March 2006). "Foundation and practice of neurofeedback for the treatment of epilepsy". Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 31 (1): 21–35. doi:10.1007/s10484-006-9002-x. PMID 16614940. S2CID 1445660.

- ↑ Tan G, Thornby J, Hammond DC, Strehl U, Canady B, Arnemann K, Kaiser DA (July 2009). "Meta-analysis of EEG biofeedback in treating epilepsy". Clinical EEG and Neuroscience. 40 (3): 173–9. doi:10.1177/155005940904000310. PMID 19715180. S2CID 16682327.

- ↑ Egner T, Gruzelier JH (July 2003). "Ecological validity of neurofeedback: modulation of slow wave EEG enhances musical performance". NeuroReport. 14 (9): 1221–4. doi:10.1097/00001756-200307010-00006. PMID 12824763.

- 1 2 Gruzelier J (1 July 2011). "Neurofeedback and the performing arts". Neuroscience Letters. 500: e15. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2011.05.106. S2CID 54308374.

- ↑ Doppelmayr M, Weber E (20 May 2011). "Effects of SMR and Theta/Beta Neurofeedback on Reaction Times, Spatial Abilities, and Creativity". Journal of Neurotherapy. 15 (2): 115–129. doi:10.1080/10874208.2011.570689.

- ↑ Beyerstein BL (1990). "Brainscams: Neuromythologies of the New Age". International Journal of Mental Health. 19 (3): 27–36. doi:10.1080/00207411.1990.11449169.

- ↑ Vernon D, Dempster T, Bazanova O, Rutterford N, Pasqualini M, Andersen S (30 Nov 2009). "Alpha Neurofeedback Training for Performance Enhancement: Reviewing the Methodology". Journal of Neurotherapy. 13 (4): 214–227. doi:10.1080/10874200903334397.

- ↑ Edmonds WA, Tenenbaum G, eds. (2011-11-25). Case Studies in Applied Psychophysiology. doi:10.1002/9781119959984. ISBN 9781119959984.

- ↑ Cheng MY, Huang CJ, Chang YK, Koester D, Schack T, Hung TM (December 2015). "Sensorimotor Rhythm Neurofeedback Enhances Golf Putting Performance". Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology. 37 (6): 626–36. doi:10.1123/jsep.2015-0166. PMID 26866770.

- 1 2 Kaiser DA (2005). "Basic Principles of Quantitative EEG". Journal of Adult Development. 12 (2/3): 99–104. doi:10.1007/s10804-005-7025-9. S2CID 532595.

- ↑ Kamiya, J (1962). "Conditioned discrimination of the EEG alpha rhythm in humans". Proceedings of the Western Psychological Association, San Francisco, California.

- 1 2 Kamiya J (February 2011). "The first communications about operant conditioning of the EEG". Journal of Neurotherapy. 15 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1080/10874208.2011.545764.

- ↑ Frederick JA (September 2012). "Psychophysics of EEG alpha state discrimination". Consciousness and Cognition. 21 (3): 1345–54. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2012.06.009. PMC 3424312. PMID 22800733.

- ↑ Nowlis DP, Kamiya J (January 1970). "The control of electroencephalographic alpha rhythms through auditory feedback and the associated mental activity". Psychophysiology. 6 (4): 476–84. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.1970.tb01756.x. PMID 5418812.

- ↑ Anand BK, Chhina GS, Singh B (June 1961). "Some aspects of electroencephalographic studies in yogis". Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 13 (3): 452–6. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(61)90015-3.

- ↑ Kasamatsu A, Hirai T (1966). "An electroencephalographic study on the zen meditation (Zazen)". Folia Psychiatrica et Neurologica Japonica. 20 (4): 315–36. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.1966.tb02646.x. PMID 6013341. S2CID 18861855.

- ↑ Wenger MA, Bagchi BK (October 1961). "Studies of autonomic functions in practitioners of Yoga in India". Behavioral Science. 6 (4): 312–23. doi:10.1002/bs.3830060407. PMID 14006122.

- ↑ Moss D (1998). "Biofeedback, mind-body medicine, and the higher limits of human nature". In Moss D (ed.). Humanistic and transpersonal psychology: A historical and biographical sourcebook. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing.

- ↑ Stoyva J, Kamiya J (May 1968). "Electrophysiological studies of dreaming as the prototype of a new strategy in the study of consciousness". Psychological Review. 75 (3): 192–205. doi:10.1037/h0025669. PMID 4874112.

- ↑ Brown BB (November 1970). "Awareness of EEG-subjective activity relationships detected within a closed feedback system". Psychophysiology. 7 (3): 451–64. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.1970.tb01771.x. PMID 5510820.

- ↑ Brown BB (January 1970). "Recognition of aspects of consciousness through association with EEG alpha activity represented by a light signal". Psychophysiology. 6 (4): 442–52. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.1970.tb01754.x. PMID 5418811.

- ↑ Orne MT, Wilson SK (1978). "On the nature of alpha feedback training.". In Schwartz GE, Shapiro D (eds.). Consciousness and Self-Regulation. Boston, MA: Springer. pp. 359–400.

- ↑ Hardt JV, Kamiya J (March 1976). "Conflicting results in EEG alpha feedback studies: why amplitude integration should replace percent time". Biofeedback and Self-Regulation. 1 (1): 63–75. doi:10.1007/bf00998691. PMID 990344. S2CID 45071893.

- ↑ Vernon D, Dempster T, Bazanova O, Rutterford N, Pasqualini M, Andersen S (November 2009). "Alpha neurofeedback training for performance enhancement: reviewing the methodology". Journal of Neurotherapy. 13 (4): 214–27. doi:10.1080/10874200903334397.

- ↑ Biswas A, Ray S (2019). "Alpha Neurofeedback Has a Positive Effect for Participants Who Are Unable to Sustain Their Alpha Activity". eNeuro. 6 (4): ENEURO.0498–18.2019. doi:10.1523/ENEURO.0498-18.2019. PMC 6709230. PMID 31375473.

- ↑ Sterman MB, Clemente CD (August 1962). "Forebrain inhibitory mechanisms: cortical synchronization induced by basal forebrain stimulation". Experimental Neurology. 6 (2): 91–102. doi:10.1016/0014-4886(62)90080-8. PMID 13916975.

- ↑ Sterman MB, Friar L (July 1972). "Suppression of seizures in an epileptic following sensorimotor EEG feedback training". Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 33 (1): 89–95. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(72)90028-4. PMID 4113278.

- 1 2 Sterman MB (January 2000). "Basic concepts and clinical findings in the treatment of seizure disorders with EEG operant conditioning". Clinical Electroencephalography. 31 (1): 45–55. doi:10.1177/155005940003100111. PMID 10638352. S2CID 43506749.

- ↑ Lubar JF, Swartwood MO, Swartwood JN, O'Donnell PH (1995). "Evaluation of the effectiveness of EEG neurofeedback training for ADHD in a clinical setting as measured by changes in TOVA scores, behavioral ratings, and WISC-R performance". Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 20 (1): 83–99. doi:10.1007/bf01712768. PMID 7786929. S2CID 19193823.

- ↑ Hammond DC. "Neurotherapy also called Neurofeedback or EEG Biofeedback". Applied Neuroscience Society of Australasia. Applied Neuroscience Society of Australasia. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 Sokhadze TM, Cannon RL, Trudeau DL (March 2008). "EEG biofeedback as a treatment for substance use disorders: review, rating of efficacy, and recommendations for further research". Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 33 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1007/s10484-007-9047-5. PMC 2259255. PMID 18214670.

- ↑ Reel JJ (2013). Eating Disorders: An Encyclopedia of Causes, Treatment, and Prevention. ABC-CLIO. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-4408-0058-0.

- ↑ Thornton K, Carmody D (2009). "Eyes-Closed and Activation QEEG Databases in Predicting Cognitive Effectiveness and the Inefficiency Hypothesis". Journal of Neurotherapy. 13 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1080/10874200802429850.

- ↑ "Biofeedback Federation of Europe – BFE".

- ↑ Neblett R, Shaffer F, Crawford J (2008). "What is the value of Biofeedback Certification Institute of America certification?". Biofeedback. 36 (3): 92–94.

- ↑ "Biofeedback Rules". WAC 296-21-280. Washington State Legislature.

- ↑ Gevirtz R (2003). "The behavioral health provider in mind-body medicine.". In Moss D, McGrady A, Davies TC, Wickramasekera I (eds.). Handbook of mind-body medicine for primary care. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- ↑ De Bease C (2007). "Biofeedback Certification Institute of America certification: Building skills without walls". Biofeedback. 35 (2): 48–49.

- ↑ Shaffer F, Schwartz MA. "Entering the field and assuring competence.". In Schwartz MS, Andrasik F (eds.). Biofeedback: A practitioner's guide (4th ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

- 1 2 Ros T, Munneke MA, Ruge D, Gruzelier JH, Rothwell JC (February 2010). "Endogenous control of waking brain rhythms induces neuroplasticity in humans". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 31 (4): 770–8. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07100.x. PMID 20384819. S2CID 16969327. Lay summary – Science Daily.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|lay-url=(help) - ↑ Thibault RT, Raz A (October 2017). "The psychology of neurofeedback: Clinical intervention even if applied placebo". The American Psychologist. 72 (7): 679–688. doi:10.1037/amp0000118. PMID 29016171. S2CID 4650115.

- ↑ Thibault RT, Lifshitz M, Birbaumer N, Raz A (2015-05-23). "Neurofeedback, Self-Regulation, and Brain Imaging: Clinical Science and Fad in the Service of Mental Disorders". Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 84 (4): 193–207. doi:10.1159/000371714. PMID 26021883. S2CID 17750375.

- ↑ Schabus M, Griessenberger H, Gnjezda MT, Heib DP, Wislowska M, Hoedlmoser K (April 2017). "Better than sham? A double-blind placebo-controlled neurofeedback study in primary insomnia". Brain. 140 (4): 1041–1052. doi:10.1093/brain/awx011. PMC 5382955. PMID 28335000.

- ↑ Office of the Commissioner (2020-03-24). "FDA permits marketing of first medical device for treatment of ADHD". FDA. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

Further reading

{{cite book}}: Check |isbn= value: length (help)

- Arns M, Sterman MB (2019). Neurofeedback: How it all started. Nijmegen, The Netherlands: Brainclinics Insights. ISBN 9789083001302.

- Evans JR, Abarbanel A (1999). An introduction to quantitative EEG and Neurofeedback. San Diego: Academic Press.

- Hill RW, Robert W, Eduardo C (15 May 2009). Healing Young Brains: The Neurofeedback Solution (1st ed.). Hampton Roads Publishing.

- Robbins J (2008). A Symphony in the Brain – The Evolution of the New Brainwave Biofeedback (2nd ed.). Grove Atlantic.

- Steinberg M, Othmer S (2004). ADD: The 20-Hour Solution. Bandon OR: Robert Reed Publishers.