Echinostoma revolutum

| Echinostoma revolutum | |

|---|---|

| |

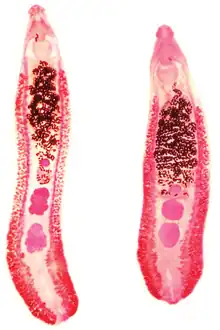

| Two specimens of Echinostoma revolutum, from:[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes |

| Class: | Trematoda |

| Order: | Plagiorchiida |

| Family: | Echinostomatidae |

| Genus: | Echinostoma |

| Species: | E. revolutum |

| Binomial name | |

| Echinostoma revolutum (Fröhlich, 1802) Looss, 1899 | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Echinostoma revolutum is a trematode parasites, of which the adults can infect birds and mammals, including humans. In humans, it causes echinostomiasis.[1]

Morphology

The worms are leaflike, elongated, and an average of 8.8 mm long (8.0–9.5 mm) and 1.7 mm wide (1.2–2.1 mm). When first passed in the feces, they were pinkish red and coiled in a "c" or "e" shape. The eggs in uteri were an average of 105 μm long (97–117 μm) and 63 μm wide (61–65 μm).[1]

a-e)Echinostoma revolutum

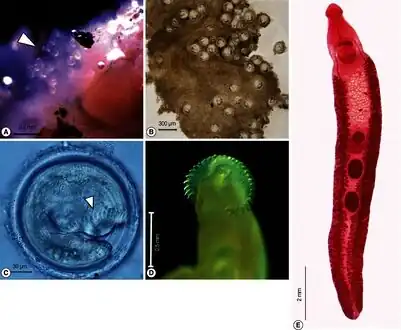

a-e)Echinostoma revolutum_in_their_snail_hosts_at_high_latitudes.png.webp) Cercariae of Echinostoma revolutum from snails

Cercariae of Echinostoma revolutum from snails

Life cycle

Infection of Echinostoma revolutum usually results from ingestion of raw snails or frogs that serve as an intermediate host. This parasite is predominantly found throughout North America. Two asexual generations occur in a snail or mollusc.[3] The first snail host is penetrated by a miracidium, producing a sporocyst. Many sporocysts are produced and mother rediae emerge. Mother rediae asexually reproduce daughter rediae, which also multiply. Each rediae then develop into a cercariae, which penetrates a second host. The second host could be another snail or a tadpole, in which development into metacercaria occurs. Cercariae typically find a snail host through chemotaxis. The cercariae are attracted to the slime of the snail, which contains small peptides. The first larval stage is the miracidium, and are found to be attracted to macrocmolecular glycoconjugates associated with a possible snail host. Environmental stimuli such as light and gravity can also be used to assist in searching for a host.

Intermediate hosts

Intermediate hosts of Echinostoma revolutum include:

- Anentome helena [4] (formerly Clea helena)

- Bithynia funiculata [4]

- Bithynia siamensis siamensi [4]

- Corbicula producta [1]

- Eyriesia eyriesi [4]

- Filopaludina sumatrensis polygramma [4]

- Filopaludina martensi martensi [4]

- Filopaludina spp.[5]

- Idiopoma doliaris [4] (formerly Filopaludina doliaris)

- Lymnaea stagnalis[6]

- Lymnaea sp. in Thailand[1]

- Physa occidentalis[1]

- Radix auricularia[7]

Distribution

Echinostoma revolutum is the most widely distributed species of the known 20 Echinostomatidae species; it is found in Asia, Oceania, Europe, and the Americas.[8] In Asian countries the disease is endemic to humans. Outbreaks have been reported in North America after travellers returned from Kenya and Tanzania.[9]

In humans

In Pursat Province, Cambodia, children eating undercooked snails or clams were identified as a possible source of infection in humans.[1]

Symptoms

Signs of infection in humans due to this type of fluke can result to weakness and emaciation. In cases where infection is heavy, hemorrhagic enteritis can occur.

Diagnosis

Echinostoma revolutum could be detected through observing feces containing eggs under a microscope.

Treatment

Albendazole and praziquantel[1] are typically prescribed to rid the parasite from the body.

Prevalence

The first reported human infection was in Taiwan in 1929.[1] The prevalence of Echinostoma revolutum trematodes in Taiwan during 1929–1979 varied from 0.11% to 0.65%.[1] Small Echinostoma revolutum–endemic foci or a few cases of human infection were discovered in the People's Republic of China, Indonesia, and Thailand until 1994.[1] However, no information is available about human Echinostoma revolutum infection after 1994, even in areas where the parasite was previously endemic.[1] In 2007 prevalence of E. revolutum adults in school children in Pursat Province, Cambodia ranged from 7.5% to 22.4%.[1]

Authors reported echinostomiasis as an endemic trematode infection among schoolchildren in Pursat.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Sohn, Woon-Mok; Chai, Jong-Yil; Yong, Tai-Soon; Eom, Keeseon S.; Yoon, Cheong-Ha; Sinuon, Muth; Socheat, Duong; Lee, Soon-Hyung (2011). "Echinostoma revolutumInfection in Children, Pursat Province, Cambodia". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 17 (1): 117–9. doi:10.3201/eid1701.100920. PMC 3204640. PMID 21192870. Archived from the original on 2020-08-10. Retrieved 2023-03-07..

- ↑ Chai, Jong-Yil; Cho, Jaeeun; Chang, Taehee; Jung, Bong-Kwang; Sohn, Woon-Mok (2020). "Taxonomy of Echinostoma revolutum and 37-collar-spined Echinostoma spp.: A historical review". The Korean Journal of Parasitology. 58 (4): 343–371. doi:10.3347/kjp.2020.58.4.343. PMC 7462802. PMID 32871630.

- ↑ Pantoja, Camila; Faltýnková, Anna; O’Dwyer, Katie; Jouet, Damien; Skírnisson, Karl; Kudlai, Olena (2021). "Diversity of echinostomes (Digenea: Echinostomatidae) in their snail hosts at high latitudes". Parasite. 28: 59. doi:10.1051/parasite/2021054. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC 8336728. PMID 34319230.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Chantima, Kittichai; Chai, Jong-Yil; Wongsawad, Chalobol (2013). "Echinostoma revolutum: Freshwater snails as the second intermediate hosts in Chiang Mai, Thailand". The Korean Journal of Parasitology. 51 (2): 183–189. doi:10.3347/kjp.2013.51.2.183. PMC 3662061. PMID 23710085.

- ↑ Chai, Jong-Yil; Sohn, Woon-Mok; Na, Byoung-Kuk; Van De, Nguyen (2011). "Echinostoma revolutum : Metacercariae in Filopaludina snails from Nam Dinh Province, Vietnam, and adults from experimental hamsters". The Korean Journal of Parasitology. 49 (4): 449. doi:10.3347/kjp.2011.49.4.449. PMID 22355218. S2CID 29211176.

- ↑ Soldanova, Miroslava; Selbach, Christian; Sures, Bernd; Kostadinova, Aneta; Perez-Del-Olmo, Ana (2010). "Larval trematode communities in Radix auricularia and Lymnaea stagnalis in a reservoir system of the Ruhr River". Parasites & Vectors. 3: 56. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-3-56. PMC 2910012. PMID 20576146.

- ↑ "Echinostomum revolutum (Parasite Species Summary)". Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2008-10-22. accessed 22 October 2008

- ↑ Chai, Jong-Yil (2009). "Echinostomes in humans". The Biology of Echinostomes. Springer New York. pp. 147–183. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-09577-6_7. ISBN 978-0-387-09576-9. Archived from the original on 2023-09-16. Retrieved 2023-03-07.

- ↑ Poland, Gregory A.; Navin, Thomas R.; Sarosi, George A. (1985). "Outbreak of parasitic gastroenteritis among travelers returning from Africa". Archives of Internal Medicine. 145 (12): 2220–2221. doi:10.1001/archinte.1985.00360120092015. PMID 4074036.

Further reading

Kelly, Cynthia (2009). "Echinostoma revolutum". Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 2017-02-17.