Enterovirus 71

| Enterovirus A71 | |

|---|---|

| |

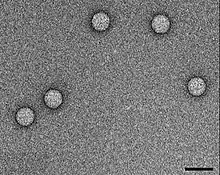

| TEM micrograph of Enterovirus A71 virions. Scale bar, 50 nm. | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Pisuviricota |

| Class: | Pisoniviricetes |

| Order: | Picornavirales |

| Family: | Picornaviridae |

| Genus: | Enterovirus |

| Species: | Enterovirus A |

| Serotype: | Enterovirus A71 |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Enterovirus 71 (EV71), also known as Enterovirus A71 (EV-A71), is a virus of the genus Enterovirus in the Picornaviridae family,[1] notable for its role in causing epidemics of severe neurological disease and hand, foot, and mouth disease in children.[2] It was first isolated and characterized from cases of neurological disease in California in 1969.[3][4] Enterovirus 71 infrequently causes polio-like syndrome permanent paralysis.[5]

Structure and genome

Enterovirus 71 is a single-stranded plus-stranded RNA genome, with some 7400 bases.EVA is non-enveloped, and symmetrical. Furthermore, it is a 20–30 nm icosahedral capsid.In turn the genome encodes one polyprotein (2200 amino acid residues).[6][7]

The receptors for EV71 (and CVA16[8]) have been identified as P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 and scavenger receptor class B, member 2 (SCARB2); both are transmembrane proteins.[9]

The basic reproductive number (R0) for enterovirus 71 (EV71) was estimated to a median of 5.48 with an interquartile range of 4.20 to 6.51.[10]

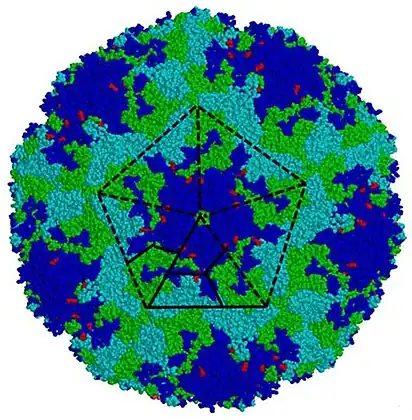

Eneterovirus 71 (EV71) genotype A virus particle.

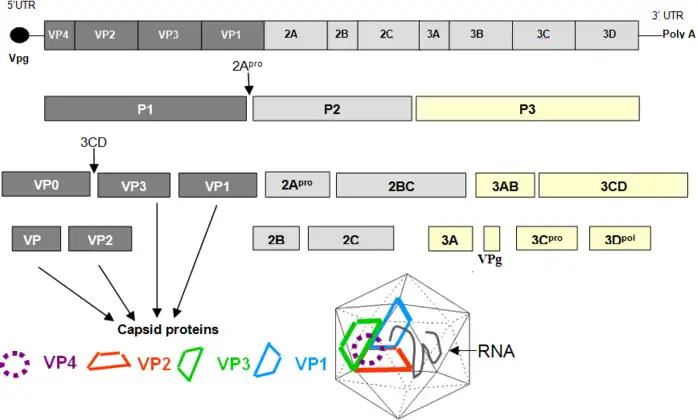

Eneterovirus 71 (EV71) genotype A virus particle. Organisation of the enterovirus genome, polyprotein processing cascade and architecture of enterovirus capsid. The genome of enteroviruses contains one single open reading frame flanked by a 5′-and 3’ untranslated regions (UTR). A small viral protein, VPg, is covalently linked to the 5′ UTR. The 3’UTR encoded poly(A) tail. The translation of the genome results in a polyprotein which is cleaved into four structural proteins and seven non-structural proteins. The sites of cleavage by viral proteinases are indicated by arrows. The four structural proteins adopte an icosahedral symmetry with VP1, VP2 and VP3 located at the outer surface of the capsid and VP4 at the inner surface. The single strand genomic RNA is located inside the capsid.[11]

Organisation of the enterovirus genome, polyprotein processing cascade and architecture of enterovirus capsid. The genome of enteroviruses contains one single open reading frame flanked by a 5′-and 3’ untranslated regions (UTR). A small viral protein, VPg, is covalently linked to the 5′ UTR. The 3’UTR encoded poly(A) tail. The translation of the genome results in a polyprotein which is cleaved into four structural proteins and seven non-structural proteins. The sites of cleavage by viral proteinases are indicated by arrows. The four structural proteins adopte an icosahedral symmetry with VP1, VP2 and VP3 located at the outer surface of the capsid and VP4 at the inner surface. The single strand genomic RNA is located inside the capsid.[11]

Evolution

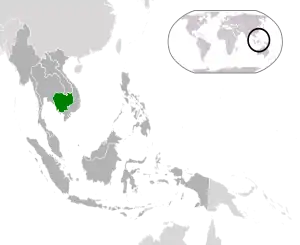

This virus is a member of the enterovirus species A. [12] This virus appears to have evolved only recently with the first known strain isolated in the late 1960's, it was associated with an outbreak of neurological disease in the United States in 1969. It then spread to Europe with outbreaks there in Bulgaria (1975) and Hungary (1978). It has since spread to various countries in Asia where it has been responsible for several outbreaks, most recently in Cambodia (2012).[13][14][15]

The strains fall into six genogroups named A to F.[16] Both the B and C genogroups have been subdivided into B0–B5 and C1–C5. The genogroup C appears to have evolved ~1970 while the A and B taxa evolved prior to this. Genogroup D was identified in India only and genogroups E and F in Africa only. Phylogenetic studies performed on partial sequences of viruses from India suggest that additional genogroups exist.[16]

An analysis of strains isolated in Europe (Austria, France and Germany) showed that the clades C1b and C2b originated in 1994 (95% confidence interval 1992.7–1995.8) and 2002 (95% confidence interval 2001.6–2003.8), respectively.[17]

Intra- and inter-typic recombination occur commonly in EV-A71 virus infections.[18] Recombination can occur when at least two viral genomes are present in the same host cell. The mechanism of recombination likely involves strand switching by the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (copy-choice recombination),[18] a mechanism demonstrated in poliovirus.[19] In addition to being a source of sequence diversity, recombination in RNA viruses appears to be an adaptation for repairing genome damage.[20][21]

Disease

Enterovirus 71 is the second-most common cause of Hand, foot and mouth disease.[22] Many other strains of enterovirus can also be responsible.[22]

There is no antiviral agent known to be effective in treating EV71 infection.[23] However, Sinovac Biotech Ltd., a pharmaceutical company in China, conducted an experimental trial for an EV71 vaccination, which was completed in March 2013. In December 2015, the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) approved the first EV71 vaccine.[24] The vaccine was administered to approximately 10,000 children between the ages of 6 and 35 months. Of the placebo group, there were 30 cases of hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) reported, and 41 cases of any EV71-associated illness. This can be compared to only 3 cases of HFMD and eight cases of any EV71-related illness reported in the vaccine group. Participants were surveilled from day 56 until the end of the 14-month experiment period, in addition to checkups at months five, eight, eleven, and fourteen.[25] Other experimental vaccines and antiviral agents are being researched.[26][27] For example, "both bovine and human lactoferrins were found to be potent inhibitors of EV71 infection"[2] and "ribavirin could be a potential anti-EV71 drug."[28]

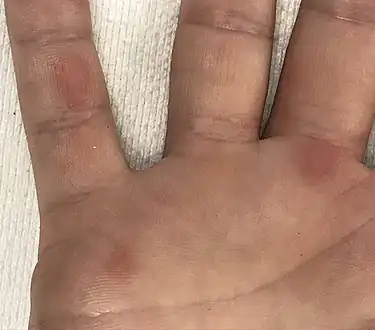

Hand foot and mouth disease on childs feet

Hand foot and mouth disease on childs feet Rash on hand and feet of a 36-year-old man

Rash on hand and feet of a 36-year-old man Close up of the lesions

Close up of the lesions.jpg.webp) Spots on tongue

Spots on tongue

Outbreaks

China

HFMD was recognized in China in the 1980s, and EV71 was first isolated in China from HFMD vesicle fluid in 1987 by Zhi-Ming Zheng at Virus Research Institute, Hubei Medical University.[29][30] From 1999 to 2004, there were no epidemics of hand, foot, and mouth disease in Shenzhen, People's Republic of China, but each year there were small, local outbreaks associated with only a few cases of neurological disease and no reported fatalities. Genetic analysis revealed 19 cases of EV71 among 147 children who had hand, foot, and mouth disease in Shenzhen during this time.[31] Until 2008, no large EV71 epidemic had been reported on the Chinese mainland, but sporadic infections were common in the southeast coastal area as well as in inland regions, such as Beijing, Chongqing, and Jinan. From 1998 to 2004, the only EV71 viruses identified on mainland China belonged to the genotype C4, indicating far less variety in China than in Taiwan.[31]On May 3, 2008, Chinese health authorities reported a major outbreak of EV71 enterovirus in Fuyang City and other localities in Anhui, Zhejiang, and Guangdong provinces. As of May 3, 2008, 3736 cases occurring mainly in children were reported, with 22 dead and 42 critically ill. Some 415 new cases were reported in 24 hours in Fuyang City alone.[32][33] In the end there were more than 48,000 cases and 21 deaths due to the virus.[34]

Specifically, an additional 5,151 cases were reported in Anhui province, with scores more in 4 other provinces. 8,531 cases of children infected with hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD) were reported in China. All the children infected were aged below 6, with most of them being under 2.[35][36][37] As of May, 7 contagious HFMD led to 28 deaths.[38] Xinhua reported the number of people infected also rose from 4,000 to 15,799.[39]

Taiwan

In Taiwan in 1998, Enteroviruses were isolated from a total of 1,892 individuals. Of the virus isolates, enterovirus 71 (EV71) was diagnosed in 44.4% of the patients in 1998, 2% in 1999, and 20.5% in 2000. Genetic analyses of the 5′-untranslated and VP1 regions of EV71 isolates by reverse transcription-PCR and sequencing were performed to understand the diversity of EV71 in these outbreaks of HFMD. Most EV71 isolates from the 1998 epidemic belonged to genotype C, while only one-tenth of the isolates were genotype B. All EV71 isolates tested from 1999 to 2000 belonged to genotype B. This study indicated that two genogroups of EV71 capable of inducing severe clinical illness had been circulating in Taiwan. Furthermore, the predominant EV71 genotypes responsible for each of the two major HFMD outbreaks within the 3-year period in Taiwan were different.[40][41][42][43]

Significant outbreaks of the Enterovirus 71 (EV71) occurred in 1998, 2000 and 2001 with 78 deaths in 1998, 25 in 2000 and 26 in 2001. There are two patterns observed in outbreaks of the virus 1) where they may be small with occasional cases resulting in death or 2) they are severe with a high fatality rate. The 1998 outbreak came in two waves to Taiwan. The first wave reached its peak of fatalities in the week of June 7 with cases in all four regions of Taiwan. There were approximately 405 severe cases and 91% of fatal cases were children of under the age of five.[43] After further investigation into the fatalities among children 16% were six months or younger, 43% were from seven to twelve months meaning it was more fatal for children under the age of one. 65 out of 78 patients died from pulmonary edema or haemorrhage making it the most lethal effect which results from the virus.[44] Total number of cases of Hand Foot and Mouth Disease (HFMD) and herpangina in Taiwan was 129,106.[40][43]

Development and detection

The outbreaks of the Enterovirus 71 in Taiwan and the number of cases and fatalities that resulted became an indication of the significance of the threat of the virus. New anti-viral drugs should be developed and vaccination of children under five years old should be considered in areas the virus is more susceptive.[43] In July 1989 a sentinel surveillance system for infectious diseases was established in Taiwan by Disease, Surveillance and Quarantine Service, Ministry of Health of Taiwan. The sentinel surveillance system is physician based and has approximately 850 Taiwanese physicians participating from various regions all over Taiwan. Public health officers contact the physicians on a weekly basis collecting disease information and on the occasion where there is a suspected outbreak of an infectious disease they are responsible for public notification. After the observed outbreak of HFMD and herpangina in Malaysia in 1997, they were included in the detection system.[45]In March 1998, under the sentinel surveillance system, it was noticed that there was an increasing number of HFMD cases and herpangina in Taiwan. By the end of April that year, numbers of cases involving children HFMD had increased significantly.[43] Due to the presence of a possible threat of an epidemic a warning was released on May 12 for the virus and preventative measures were advised to the public such as practicing better hygiene and isolating infected children. Although public notification had been given and preventatives taken, the number of HFMD cases continued to rise. On May 29 another report system, based on hospitals rather than just physicians, was developed in response to this where all severe and fatal cases were more carefully monitored from 597 hospital and medical centres.[45]

Exact reasons behind the outbreaks are hard to and yet to be defined however through the reporting systems developed, detection of the virus is of large significance and gives way for further study and investigation. Possible reasons behind the developments of the outbreaks are that the virus may have mutated with increased virulence made it more easily contractible or that the population and genetics became more susceptible to contraction of the disease.[45] Studies for serial serum antibody titers to the Enterovirus 71 in blood samples taken yearly from 81 children born in 1988 was conducted from 1989 to 1994 and 1997 to 1999. They discovered an increase in EV71 seroconversion (increased susceptibility to the disease) from 3% to 11% from 1989 to 1997 and by 1997 68% of the children had evidence of being infected by the virus. The virus was also evident in HFMD patients from as early on as 1981.[43] Other studies conducted in early 1999 showed that half the adult population of Taiwan had antibodies against the enterovirus 71 prior to the 1998 outbreak meaning the population of children were more susceptible to the virus.[44] It is possible that prior to the outbreak in 1998 there were severe and fatal cases that went unrecognised as EV71 cases in children who died of unexplained illnesses and studies are still ongoing.[3][43]

Cambodia

From April through July 2012, at least 64 children died and two survived from a disease affecting children under 7 years old in Cambodia. Most died within 24 hours and had exhibited symptoms including respiratory illnesses, fever and generalized neurological abnormalities.[46] An initial sampling taken from 24 patients found that 15 tested positive for EV71 on July 6, 2012. The World Health Organization noted that the cause of the outbreak has not been fully solved and that more analysis was needed.[47]

On 15 July 2012, it was announced that no further cases had been noted in Cambodia, and that the deaths were a result of a combination of infections with EV 71, dengue fever, and Streptococcus suis.[48] and the use of steroids in the treatment of the infections.

Vietnam

Vietnam recorded 63,780 cases of hand, foot and mouth disease in the first seven months of 2012.[49] According to Tran Minh Dien, vice director of the National Hospital for Children, about 58.7% percent were caused by EV71.[50]

Australia

In June 2013, an outbreak of four cases was noted in Sydney. Approximately 100 more children are believed to have been infected, and a panel of doctors are monitoring the situation at present.[51]

Research

A joint UK and Chinese team working at the UK's national synchrotron facility near Oxford determined the structure of EV71 in 2012. Researchers observed movements resembling breathing in the virus, and found that this accompanied the infection process, together with a small molecule picked up from the body's cells and used to switch state. This particular molecule must be discarded in order to start an infection, and new research will be aimed at creating a synthetic replica that would bond strongly to the virus and stop the infection process.[52][53]

See also

References

- ↑ "Human enterovirus 71 polyprotein gene, complete cds". 2001-04-30. Archived from the original on 12 December 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- 1 2 Lin TY, Chu C, Chiu CH (October 2002). "Lactoferrin inhibits enterovirus 71 infection of human embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma cells in vitro". J. Infect. Dis. 186 (8): 1161–4. doi:10.1086/343809. PMID 12355368.

- 1 2 Wang, Jen-Ren; Tuan, Yen-Chang; Tsai, Huey-Pin; Yan, Jing-Jou; Liu, Ching-Chuan; Su, Ih-Jen (January 2002). "Change of Major Genotype of Enterovirus 71 in Outbreaks of Hand-Foot-and-Mouth Disease in Taiwan between 1998 and 2000". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. American Society for Microbiology. 40 (1): 10–5. doi:10.1128/JCM.40.1.10-15.2002. PMC 120096. PMID 11773085.

- ↑ SY Wang; CL Lin; HC Sun; HY Chen (25 December 1999). "Laboratory Investigation of a Suspected Enterovirus 71 Outbreak in Central Taiwan" (PDF). Epidemiology Bulletin. 15 (12): 215–219. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008.

- ↑ Schubert, Ryan D.; Hawes, Isobel A.; et al. (2019). "Pan-viral serology implicates enteroviruses in acute flaccid myelitis". Nature Medicine. 25 (11): 1748–1752. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0613-1. PMC 6858576. PMID 31636453.

- ↑ Kobayashi, Kyousuke; Koike, Satoshi (21 August 2021). "Adaptation and Virulence of Enterovirus-A71". Viruses. 13 (8): 1661. doi:10.3390/v13081661. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ↑ Yuan, Jingjing; Shen, Li; Wu, Jing; Zou, Xinran; Gu, Jiaqi; Chen, Jianguo; Mao, Lingxiang (2018). "Enterovirus A71 Proteins: Structure and Function". Frontiers in Microbiology. 9. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00286/full. ISSN 1664-302X. Archived from the original on 6 November 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ↑ Chong, Pele; Guo, Meng-Shin; Lin, Fion Hsiao-Yu; Hsiao, Kuang-Nan; Weng, Shu-Yang; Chou, Ai-Hsiang; Wang, Jen-Ren; Hsieh, Shih-Yang; Su, Ih-Jen; Liu, Chia-Chyi (2012). "Immunological and biochemical characterization of coxsackie virus A16 viral particles". PloS One. 7 (11): e49973. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049973. ISSN 1932-6203. Archived from the original on 15 June 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ↑ Nishimura Y, Shimizu H (2012). "Cellular receptors for human enterovirus species A." Front Microbiol. 3: 105. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00105. PMC 3313065. PMID 22470371.

- ↑ Ma E, Fung C, Yip SH, Wong C, Chuang SK, Tsang T (Aug 2011). "Estimation of the basic reproduction number of enterovirus 71 and coxsackievirus A16 in hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreaks". Pediatr Infect Dis J. 30 (8): 675–9. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3182116e95. PMID 21326133. S2CID 25977037.

- ↑ Hober, Didier; Sané, Famara; Riedweg, Karena; Moumna, Ilham; Goffard, Anne; Choteau, Laura; Alidjinou, Enagnon Kazali; Desailloud, Rachel (27 February 2013). Viruses and Type 1 Diabetes: Focus on the Enteroviruses. IntechOpen. ISBN 978-953-51-1017-0. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ↑ "Enterovirus A71 (EV-A71) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 25 October 2022. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ↑ Brown, B. A.; Oberste, M. S.; Alexander, J. P.; Kennett, M. L.; Pallansch, M. A. (December 1999). "Molecular epidemiology and evolution of enterovirus 71 strains isolated from 1970 to 1998". Journal of Virology. 73 (12): 9969–9975. doi:10.1128/JVI.73.12.9969-9975.1999. ISSN 0022-538X. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ↑ Bible, Jon M.; Pantelidis, Panagiotis; Chan, Paul K. S.; Tong, C. Y. William (2007). "Genetic evolution of enterovirus 71: epidemiological and pathological implications". Reviews in Medical Virology. 17 (6): 371–379. doi:10.1002/rmv.538. ISSN 1052-9276. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ↑ Puenpa, Jiratchaya; Wanlapakorn, Nasamon; Vongpunsawad, Sompong; Poovorawan, Yong (18 October 2019). "The History of Enterovirus A71 Outbreaks and Molecular Epidemiology in the Asia-Pacific Region". Journal of Biomedical Science. 26 (1): 75. doi:10.1186/s12929-019-0573-2. ISSN 1423-0127. Archived from the original on 24 July 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- 1 2 Bessaud M, et al. (March 2014). "Molecular Comparison and Evolutionary Analyses of VP1 Nucleotide Sequences of New African Human Enterovirus 71 Isolates Reveal a Wide Genetic Diversity". PLOS ONE. 9 (3): e90624. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...990624B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0090624. PMC 3944068. PMID 24598878.

- ↑ Mirand A, Schuffenecker I, Henquell C, Billaud G, Jugie G, Falcon D, Mahul A, Archimbaud C, Terletskaia-Ladwig E, et al. (2009). "Phylogenetic evidence for a recent spread of two populations of human enterovirus 71 in European countries". J Gen Virol. 91 (9): 2263–2277. doi:10.1099/vir.0.021741-0. PMID 20505012.

- 1 2 Huang SW, Cheng D, Wang JR. Enterovirus A71: virulence, antigenicity, and genetic evolution over the years. J Biomed Sci. 2019 Oct 21;26(1):81. doi: 10.1186/s12929-019-0574-1. Review. PMID 31630680

- ↑ Kirkegaard K, Baltimore D. The mechanism of RNA recombination in poliovirus. Cell. 1986 Nov 7;47(3):433-43. PMID 3021340

- ↑ Barr JN, Fearns R. How RNA viruses maintain their genome integrity. J Gen Virol. 2010 Jun;91(Pt 6):1373-87. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.020818-0. Epub 2010 Mar 24. Review. PMID 20335491

- ↑ Bernstein H, Bernstein C, Michod RE. Sex in microbial pathogens. Infect Genet Evol. 2018 Jan;57:8-25. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.10.024. Epub 2017 Oct 27. Review. PMID 29111273

- 1 2 Repass, Gregory L.; Palmer, William C.; Stancampiano, Fernando F. (1 September 2014). "Hand, foot, and mouth disease: Identifying and managing an acute viral syndrome". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 81 (9): 537–543. doi:10.3949/ccjm.81a.13132. ISSN 0891-1150. PMID 25183845. S2CID 32509752. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ↑ Lin, Jing-Yi; Kung, Yu-An; Shih, Shin-ru (3 September 2019). "Antivirals and vaccines for Enterovirus A71". Journal of Biomedical Science. 26 (65): 65. doi:10.1186/s12929-019-0560-7. PMC 6720414. PMID 31481071.

- ↑ Mao, Qun-ying; Wang, Yiping; Bian, Lianlian; Xu, Miao; Liang, Zhenglun (May 2016). "EV71 vaccine, a new tool to control outbreaks of hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD)". Expert Review of Vaccines. 15 (5): 599–606. doi:10.1586/14760584.2016.1138862. PMID 26732723. S2CID 45722352.

- ↑ Walsh, Nancy (2013-05-29). "Vaccine Blocks Hand, Foot, Mouth Disease". MedPage Today. Archived from the original on February 17, 2018. Retrieved May 30, 2013.

- ↑ Zhu, Feng-Cai; Liang, Zheng-Lun; Li, Xiu-Ling; Ge, Heng-Ming; Meng, Fan-Yue; Mao, Qun-Ying; et al. (23 March 2013). "Immunogenicity and safety of an enterovirus 71 vaccine in healthy Chinese children and infants: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 clinical trial". The Lancet. 381 (9871): 1037–1045. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61764-4. PMID 23352749. S2CID 27961719. Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ↑ Tung WS, Bakar SA, Sekawi Z, Rosli R (2007). "DNA vaccine constructs against enterovirus 71 elicit immune response in mice". Genet Vaccines Ther. 5: 6. doi:10.1186/1479-0556-5-6. PMC 3225814. PMID 17445254.

- ↑ Li ZH, Li CM, Ling P, et al. (March 2008). "Ribavirin reduces mortality in enterovirus 71-infected mice by decreasing viral replication". J. Infect. Dis. 197 (6): 854–7. doi:10.1086/527326. PMC 7109938. PMID 18279075.

- ↑ Zheng ZM, Zhang JH, Zhu WP, He PJ (1989). "First isolation of enterovirus type 71 from vesicle fluid of an adult patient with hand-foot-mouth disease in China". Virologica Sinica. 4 (4): 375–382.

- ↑ Zheng, Z. M.; He, P. J.; Caueffield, D.; Neumann, M.; Specter, S.; Baker, C. C.; Bankowski, M. J. (1995). "Enterovirus 71 isolated from China is serologically similar to the prototype E71 BrCr strain but differs in the 5'-noncoding region". Journal of Medical Virology. 47 (2): 161–167. doi:10.1002/jmv.1890470209. PMID 8830120. S2CID 24553794.

- 1 2 1

- ↑ "China on alert as virus spreads". BBC News. May 3, 2008. Archived from the original on May 6, 2008. Retrieved May 7, 2008.

- ↑ China orders heightened efforts to stop deadly virus Archived 2023-01-08 at the Wayback Machine AP News

- ↑ Sun, Li-mei; Zheng, Huan-ying; Zheng, Hui-zhen; Guo, Xue; He, Jian-feng; Guan, Da-wei; Kang, Min; Liu, Zheng; Ke, Chang-wen; Li, Jian-sen; Liu, Leng; Guo, Ru-ning; Yoshida, Hiromu; Lin, Jin-yan (2011). "An enterovirus 71 epidemic in Guangdong Province of China, 2008: epidemiological, clinical, and virogenic manifestations". Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases. 64 (1): 13–18. ISSN 1884-2836. Archived from the original on 2022-06-17. Retrieved 2023-01-12.

- ↑ "China virus toll continues rise". BBC News. May 5, 2008. Archived from the original on May 8, 2008. Retrieved May 7, 2008.

- ↑ "www.inthenews.co.uk, Hand-foot-mouth epidemic continues to infect children across China". Inthenews.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2012-02-10. Retrieved 2012-07-28.

- ↑ "6,300 sick, 26 dead in China viral outbreak | The Star". thestar.com. 5 May 2008. Archived from the original on 2017-10-22. Retrieved 2017-08-27.

- ↑ "news.xinhuanet.com, Xinhua's tally: Death toll of hand-foot-mouth disease rises to 28 in China". News.xinhuanet.com. 2008-05-07. Archived from the original on 2012-10-17. Retrieved 2012-07-28.

- ↑ "28 Chinese children die from virus". The Australian. Archived from the original on 2008-05-10. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- 1 2 Chang, Luan-Yin (August 2008). "Enterovirus 71 in Taiwan". Pediatrics and Neonatology. 49 (4): 103–112. doi:10.1016/S1875-9572(08)60023-6. ISSN 1875-9572. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ↑ Lin, Tzou-Yien; Chang, Luan-Yin; Hsia, Shao-Hsuan; Huang, Yhu-Chering; Chiu, Cheng-Hsun; Hsueh, Chuen; Shih, Shin-Ru; Liu, Ching-Chuan; Wu, Mei-Hwan (1 May 2002). "The 1998 enterovirus 71 outbreak in Taiwan: pathogenesis and management". Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 34 Suppl 2: S52–57. doi:10.1086/338819. ISSN 1537-6591. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ↑ Liu, C. C.; Tseng, H. W.; Wang, S. M.; Wang, J. R.; Su, I. J. (June 2000). "An outbreak of enterovirus 71 infection in Taiwan, 1998: epidemiologic and clinical manifestations". Journal of Clinical Virology: The Official Publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 17 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1016/s1386-6532(00)00068-8. ISSN 1386-6532. Archived from the original on 20 October 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Lin, Tzou-Yien (March 2003). "Enterovirus 71 outbreaks, Taiwan: Occurrence and Recognition". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 9 (3): 291–293. doi:10.3201/eid0903.020285. PMC 2963902. PMID 12643822.

- 1 2 Ho, Monto (23 September 1999). "An Epidemic of Enterovirus 71 in Taiwan". The New England Journal of Medicine. 341 (13): 929–935. doi:10.1056/nejm199909233411301. PMID 10498487.

- 1 2 3 Wu, Trong-Neng (May–June 1999). "Sentinel Surveillance for Enterovirus 71, Taiwan, 1998". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 5 (3): 458–460. doi:10.3201/eid0503.990321. PMC 2640775. PMID 10341187.

- ↑ Kwok, Yenni (5 July 2012). "Mystery illness claims dozens of Cambodian children". CNN. Archived from the original on 6 July 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ↑ "Officials make break in baffling disease killing Cambodian children". CNN. 8 July 2012. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ↑ "Mystery illness in Cambodia solved, doctors say". CNN.com. 11 July 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-07-12. Retrieved 2012-07-28.

- ↑ "WPRO | Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease (HFMD)". Wpro.who.int. Archived from the original on 2013-10-17. Retrieved 2012-07-28.

- ↑ "Bệnh TCM tăng 10 lần so với năm trước-Benh tay chan mieng |Suc khoe". Hn.24h.com.vn. Archived from the original on 2012-05-29. Retrieved 2012-07-28.

- ↑ "Fatal fears over 'modern polio'". 7News. 19 June 2013. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ↑ Amos, J. (17 February 2013). "Diamond to shine light on infections". BBC News. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ↑ "Flu drug 'shows promise' in overcoming resistance". BBC News. 21 February 2013. Archived from the original on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

Further reading

- "EV-A71". www.biomedcentral.com. Springer Nature. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

| Wikinews has related news: |