Everywhere at the End of Time

| Everywhere at the End of Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

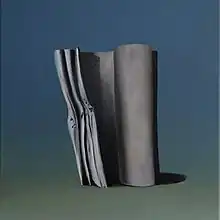

Cover art for Stage 1 | ||||

| Studio album series by the Caretaker | ||||

| Released |

| |||

| Studio | Home recording in Krakow, Poland | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 390:31 | |||

| Label | History Always Favours the Winners | |||

| Producer | Leyland Kirby | |||

| The Caretaker chronology | ||||

| ||||

Everywhere at the End of Time[lower-alpha 1] is the eleventh recording by the Caretaker, an alias of English electronic musician Leyland Kirby. Released from 2016 to 2019, its six studio albums represent the progression of Alzheimer's disease through degrading loops of ballroom recordings. Inspired by the success of An Empty Bliss Beyond This World (2011), Kirby recorded Everywhere as his final work under the alias. The albums were produced in Krakow over six-month periods to "give a sense of time passing", and used abstract paintings by his friend Ivan Seal as album covers. The series drew comparisons to composer William Basinski and electronic musician Burial, with the later stages being influenced by avant-gardist John Cage.

The complete edition presents six hours of music, portraying a range of emotions and being characterised by noise. Though the last three stages depart from Kirby's earlier ambient works, the first three are similar to An Empty Bliss. The albums reflect the patient's disorder and death, their feelings, and the phenomenon of terminal lucidity. To promote the series, Kirby partnered with anonymous visual artist Weirdcore for music videos. At first, he thought of not creating Everywhere at all, expressing concern about whether the series would be a pretentious idea; Kirby spent more time producing it than any other release of his. The album covers received coverage from a French art exhibition named after the Caretaker's final album Everywhere, an Empty Bliss (2019), a compilation of unused material.

As each stage was released, the series received increasingly positive reviews from critics; they felt emotional about the complete edition, given its length and dementia-driven concept. Considered to be Kirby's magnum opus, Everywhere at the End of Time became an Internet phenomenon in 2020, appearing in TikTok videos as a listening challenge, and was later translated into a mod for the game Friday Night Funkin' (2020). Caregivers of people with dementia also praised the albums as they increased empathy for carers among younger listeners.

Background

The Caretaker was a pseudonym of English electronic musician Leyland Kirby that sampled big band records. Kirby drew influence from the haunted ballroom scene of filmmaker Stanley Kubrick's work The Shining (1980), as heard on the alias' debut album Selected Memories from the Haunted Ballroom (1999).[1] His first records featured the ambient style that would be prominent in his last releases.[2] The Caretaker project first explored memory loss with Theoretically Pure Anterograde Amnesia (2005), a three-hour-long album portraying the disease of the same name. By 2008, Persistent Repetition of Phrases saw Kirby's work gaining critical attention and a larger fanbase.[1]

In 2011, Kirby released An Empty Bliss Beyond This World, attaining acclaim for its exploration of Alzheimer's disease.[1] Kirby explained he initially did not desire to produce more music as the Caretaker after that. However, he said "so many people liked An Empty Bliss. So I thought to myself, 'What can I do that's not just An Empty Bliss again?'" Kirby felt the only concept left to explore would be "stages of dementia."[2] It would be his final release as the Caretaker; Kirby said, "I just can't see where I can take it after this." Everywhere at the End of Time represents the "death" of the Caretaker alias itself,[1] with the sample of a track from Selected Memories reappearing at the end of Stage 6.[3]

Music and stages

"For to be capable of remembering this music as a real-time, living culture, you'd have to be in your nineties now. What Kirby presents here could be heard as the faint, faded memory-fragments of once-beloved tunes as they waver on in atrophying minds."[4]

— Simon Reynolds

The albums, which Kirby notes as exploring dementia's "advancement and totality",[5] present poetic track titles and descriptions for each stage.[6] These, in turn, represent a person with dementia and their feelings.[7][8][9] Ideas of deterioration, melancholy, confusion, and abstractness are present throughout.[10] Tiny Mix Tapes suggested that, as the swan song of the Caretaker alias, Everywhere "threatens at every moment to give way to nothing."[11] The albums feature an avant-gardist, experimental concept,[12][13][14] with music magazine Fact noting a "hauntological link" between Everywhere's ballroom style and certain subgenres of vaporwave.[15] Author Sarah Nove related the albums to Walter Benjamin's theory of aura, praising the fact that because Everywhere "exists in a virtual space, it has no physical form to which aura can be attached."[16] Noting "romance" to the series, Bandcamp Daily's Matt Mitchell wrote that while An Empty Bliss "is sequenced like a series of vignettes," Everywhere executes "years of deterioration culminating in some kind of ethereal catharsis."[17]

The series' exploration of dementia drew comparisons to The Disintegration Loops (2002–2003) by musician William Basinski.[2][10][18] However, as viewed by Spectrum Culture's Holly Hazelwood, Kirby's work does not focus on physical decay, while that record does.[10] Although positive of Basinski's works, Kirby insisted his own "aren't just loops breaking down. They're about why they're breaking down, and how."[2] The sound of Everywhere has also been compared to the style of another electronic musician, Burial;[10] author Matt Colquhoun wrote for The Quietus that both artists "highlight the 'broken time of the twenty-first century.'"[19] While reviewing the first stage, writers Adrian Mark Lore and Andrea Savage commended the record for those who enjoy ambient artists William Basinski, Stars of the Lid, and Brian Eno.[20] Throughout, certain samples return constantly—in particular, a cover of "Heartaches" (1931) by Al Bowlly—and become more degraded with each album.[10] In the last six minutes, a song from Selected Memories can be heard.[3]

With each stage, the songs get more distorted, reflecting the memory and its deterioration.[21] The jazz style of the first three stages is reminiscent of An Empty Bliss, with loops from vinyl records and wax cylinders. On Stage 3, the songs are shorter—some lasting for only one minute—and typically avoid fade-outs.[10][14] The Post-Awareness stages reflect Kirby's desire to "explore complete confusion, where everything starts breaking down."[13] The two penultimate stages present chaos in their music, representing the patient's altered perception of reality.[22] The final stage consists of drones, portraying the emptiness of the afflicted person's mind.[18] In its last 15 minutes, it features an organ, choral, and a minute of silence, portraying death.[18][23] Miles Bowe of Pitchfork wrote about the contrast of the later stages to Kirby's other ambient works as "evolving its sound in new and often frightening ways",[24] while Kirby described the series to be "more about the last three [stages] than the first three."[2]

Stages 1–3

| Everywhere at the End of Time – Stages 1–3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

From left to right: Beaten Frowns After (2016), Pittor Pickgown in Khatheinstersper (2015) and Hag (2014) | ||||

| Box set by the Caretaker | ||||

| Released |

| |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length |

| |||

| The Caretaker chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Audio sample | ||||

A1 – "It's Just a Burning Memory"[lower-alpha 2]

| ||||

Stage 1 is described as the initial signs of memory deterioration, being the closest album in the series to "a beautiful daydream."[5] Like An Empty Bliss,[25] it features the opening seconds of records from the 1930s looped for long lengths. Its samples present pitch changes, reverberation, overtones, and vinyl crackle.[26] The album features a range of emotions, mostly by the notions its song titles invoke;[10][27] names such as "Into each other's eyes" are sometimes interpreted as a romantic memory of the patient,[28] while more ominous titles, such as "We Don't Have Many Days", point to the patient recognizing their own mortality.[29] Despite being an upbeat release by the Caretaker,[30] some of its joyful big band compositions are more distorted than normal.[25][31] One reviewer likened it to Stanley Kubrick's Eyes Wide Shut (1999) and the works of filmmaker Woody Allen, specifying the "elegance" of Kubrick's film and the dramatic avidity of Allen's work.[32] In contrast with the first stage's joyful sound, Kirby described the second stage as having "a massive difference between the moods."[1]

Stage 2 is described as the "self-realisation that something is wrong with a refusal to accept that."[5] The album features a more emotional tone than Stage 1, with more melancholic, degraded and droning samples.[10][33][34] Its source material features more abrupt endings, exploring a hauntological ambience.[34] Track titles present more sombre themes, with names such as "Surrendering to Despair", "Last Moments of Pure Recall", and "The Way Ahead Feels Lonely", representing the patient's awareness of their disorder and the sorrow accompanying it. The songs play for longer times and feature fewer loops, but are more deteriorated in quality,[10] symbolising the patient's realisation that something seems wrong with their memories and the denial accompanying that feeling.[35] Kirby described the second stage as the one where a person "probably tries and remember more than [they] usually would",[1] with "A Losing Battle Is Raging" representing a transition between the first and second stages.[28]

Stage 3 is described as the patient experiencing "some of the last coherent memories before confusion fully rolls in and the grey mists form and fade away."[5] Samples from other works, such as those of An Empty Bliss, return with an underwater-like sound, portraying the patient's growing despair and struggle to keep their memories. While other stages presented common fade-outs on tracks, songs of Stage 3 end abruptly. The track titles become more abstract, combining the names of songs from previous stages; this results in phrases such as "Hidden Sea Buried Deep", "To the Minimal Great Hidden", and "Burning Despair Does Ache". The record focuses on the patient's awareness, being the most similar to An Empty Bliss in the entire series.[10] Kirby echoed this sentiment, explaining Stage 3 is "the most like An Empty Bliss because it's the blissful stage where you're unaware you've actually got dementia."[2] The final tracks of the records are the final recognizable melodies, although some nearly lose their melodic qualities; in Kirby's description, Stage 3 represents "the last embers of awareness before we enter the post awareness stages."[5][29]

The opening track of Stage 1, "It's Just a Burning Memory", introduces the sample of Al Bowlly's "Heartaches" that gets degraded throughout the series;[10] according to Kirby, Bowlly is "one of the main guys" sampled in the Caretaker alias.[2] In the third track of Stage 2, "What Does It Matter How My Heart Breaks", "Heartaches" returns with a lethargic style,[10] using a different cover of the same song. This specific version, in contrast to its Stage 1 counterpart, sounded downbeat to Kirby.[1] By the third stage, there is the last coherent version of "Heartaches" on "And Heart Breaks", where its horn aspects become more similar to white noise.[10] The songs sampling "Heartaches" take their title from the sample's lyrics, which surround themes of memory; Bowlly sings, "I can't believe it's just a burning memory / Heartaches, heartaches / What does it matter how my heart breaks?".[36]

Stages 4–6

| Everywhere at the End of Time – Stages 4–6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

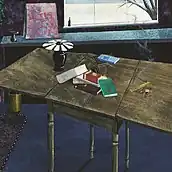

From left to right: Giltsholder (2017), Eptitranxisticemestionscers Desending (2017) and Necrotomigaud (2018) | ||||

| Box set by the Caretaker | ||||

| Released |

| |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length |

| |||

| The Caretaker chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Audio samples | ||||

H1 – "Post Awareness Confusions"

| ||||

R1 – "Place in the World Fades Away"

| ||||

Stage 4 is described as the point where "the ability to recall singular memories gives way to confusions and horror."[5] It presents a style more akin to noise, as opposed to the first three stages which featured the same style as An Empty Bliss.[10] Marking the start of the "Post-Awareness" stages,[37][38] its compositions occupy whole vinyl sides.[39] They present clinical names: three of them—G1, H1, and J1—titled "Post Awareness Confusions" and one of them—I1—titled "Temporary Bliss State". The incoherent melodies introduce a surreal aspect to the series, with some writers opining that this prepares the listener for the last two stages.[22][24] Most compositions ignore the alias' previous aspects, with far more distortion than in previous stages. However, "Temporary Bliss State" is a track calmer than the "Post Awareness Confusions", featuring a more ethereal sound. The album's ambience has been likened by Bowe to experimental musician Oval's album 94 Diskont (1995),[24] while Hazelwood claimed Stage 4's "aural horror" serves as the representation of "echoes of melody and memory".[10]

Stage 5 is described as having "more extreme entanglements, repetition and rupture [that] can give way to calmer moments."[5] The album expands its noise influence, with similarities to musicians such as Merzbow and John Wiese. In it, coherent melodies lose their significance, being replaced by overlapped samples. Hazelwood interpreted it as "a traffic jam in audio form", likening it to neurons that become filled with beta amyloids. The record differs heavily from previous albums,[10] with its source material sometimes being reduced to a whisper. According to Falisi, it does not have a sense of comfort; contrary to Stage 1's first signs, Stage 5 presents complete disorder.[40] The record has the greatest inclusion of vocals of the series, including recognizable English lyrics; near the end of the opening track, a man announces, "This selection will be a mandolin solo by Mr. James Fitzgerald."[41][42] In line with Stage 4, Stage 5's track titles are also clinical, featuring references to cerebral aspects such as plaque, entanglements, synapses, and the retrogenesis hypothesis; Hazelwood considered names such as "Advanced Plaque Entanglements" to be documenting inhumanity.[10]

Unlike previous stages, Stage 6's description features only one sentence: "Post-Awareness Stage 6 is without description."[5] According to UWIRE's Esther Ju, Stage 6 is the most interpretative record of the series, though "most would describe it as the sounds of the void."[43] Although Stage 5 had snippets of instruments, Stage 6 features empty, vague compositions, which Hazelwood interpreted as representing the patient's lack of feelings. Rather than the previously clinical names, the song titles on the final record feature more emotional phrases, such as "A Brutal Bliss Beyond This Empty Defeat".[10] It is the most distant from the sound of An Empty Bliss, portraying the patient's anxiety.[18] Rather than the voices of Stage 5, this record features sounds of hiss and crackling;[44] in general, it consists of sound collages where the music is audible yet distant.[23][45] After the release of Stage 6, Kirby announced on a YouTube comment of the complete edition the following statement: "Thanks for the support through the years. May the ballroom remain eternal. C'est fini."[lower-alpha 3][5]

Finishing the series, "Place in the World Fades Away" features organ drones in its last minutes, which have been compared to the 2014 film Interstellar and its soundtrack.[46] The music eventually cuts out to a needle drop.[10][18][23] The climax of Everywhere, six minutes before the project's end, features a clear choral sourced from a degraded vinyl record.[18] The series ends with a minute of silence, representing the death of the patient. The moment evoked different interpretations from commentators: Hazelwood suggested it represents terminal lucidity, a phenomenon where patients experience clarity briefly before death,[10] while Falisi has written about it as portraying the patient's soul moving to the afterlife.[44] The last six minutes sample the aria "Lasst Mich Ihn Nur Noch Einmal Küssen" ("Just Let Me Kiss Him One More Time") of the St Luke Passion, BWV 246. The song was also used on the Caretaker's Selected Memories album on the track "Friends Past Reunited",[3] which is also the name of a track from A Stairway to the Stars (2001). This was interpreted by one reviewer as the Caretaker alias in a "full circle moment."[41]

Production

Kirby produced Everywhere at the End of Time at his flat in Krakow using a computer "designed specifically for the production of music". Due to his prolific way of working, he made more tracks for the first stage alone than in the alias' entire history. The albums were produced a year before they were released, with the creation of Stage 3 starting in September 2016 and Stage 6 in May 2018.[1][47] Kirby stated that the first three stages have "subtle but crucial differences," as they present the same general style "based on the mood and the awareness that a person with the condition would feel."[48] Kirby wanted the mastering process, as done by Andreas "Lupo" Lubich,[49] to be "consistent sounding all the way through". He said a "strategy" was to use covers of the same samples to achieve certain emotional messages with each. Rather than buying records at physical stores as with An Empty Bliss, Kirby found most of the samples online, stating, "It's possible to find ten versions of one song now." One difference Kirby noted between Stage 1 and Stage 2 is that, while the first stage looped short sections of songs, the second stage would let the samples fully play. Describing Stage 3 to be the most similar to An Empty Bliss, Kirby states Stages 1–3 may be listened to on shuffle due to their similarities, saying that the intention of the first albums was for them to feature interchangeable compositions.[1] Between the release of the third and fourth stages, Kirby released We, So Tired of All the Darkness in Our Lives, and announced he was "moving house and studio."[50]

Kirby's production focus was on the last three stages;[1][2][51] one challenge he faced in their creation was creating what he called a "listenable chaos." Kirby added that, while producing Stage 4, he realised that the final three stages "had to be made from the viewpoint of post-awareness." Explaining the name, Kirby titled them "Post-Awareness" because they are when the patient is not aware of a disorder—anosognosia.[48] Kirby reported a feeling of pressure while working on the final three stages, saying, "I'd be finishing one stage, mastering another, all whilst starting another stage." In composing the fourth and fifth stages, Kirby claimed he possessed over 200 hours of music and "compiled it based on mood".[51] The Believer's Landon Bates likened Stage 4 to "Radio Music" (1956) by composer John Cage, to which Kirby responded that Cage's aleatoric music was employed in the later stages.[48] He said Stage 5 has "a distinct change" when compared to Stage 4, writing that "it's not immediate but it's a crucial symptom." Kirby said what he was interested in for Stage 6 was removing specific frequencies of the samples, which modern software is capable of.[1] According to Kirby, the production of the final stage was the hardest, due to the public's expectations and "the weight of the previous five [stages] falling all on this now."[48]

Artwork and packaging

"You can't trust any memories at all, can you? Because it's all glitched [and] nonsense in a way."[52]

— Ivan Seal

The album covers for Everywhere at the End of Time are abstract oil paintings by Kirby's long-time friend Ivan Seal.[53] They become less recognizable as the series progresses and are minimalist in style, presenting a single object in an empty room with no text.[31][54] Tiny Mix Tapes included Beaten Frowns After—the artwork for Stage 1—in two listings of the best album covers of 2016 and the 2010s.[55][56] Some have compared Kirby and Seal: both were born in England and became friends in Berlin, and both present similarities in the way they produce art.[53] Seal paints objects based on memory, saying, "painting like this works more like a brain".[52]

The paintings used for the album covers of the first three stages are titled Beaten Frowns After (2016), Pittor Pickgown in Khatheinstersper (2015) and Hag (2014), respectively.[57][58] Beaten Frowns After features a grey unravelling scroll on a vacant horizon, with newspaper folds similar to a brain's creases,[31] which Teen Ink writer Sydney Leahy likened to the patient unravelling their awareness of the disease.[54] Pittor Pickgown in Khatheinstersper portrays four wilting flowers in an abstract vase;[54][59] according to Falisi, the object represents "the only thing behind our bodies", which Beaten Frowns After portrays as humans themselves.[34] Hag presents a kelp plant distorted to an extreme, which Sam Goldner of Tiny Mix Tapes described as "a vase spilling out into ripples of disorder."[54][59]

The paintings for the final three stages are respectively titled Giltsholder (2017), Eptitranxisticemestionscers Desending (2017) and Necrotomigaud (2018).[58] Giltsholder is the first artwork to present a human figure in the form of a blue and green bust, although it has unrecognizable facial features. According to Goldner, the figure seems to be smiling if viewed from a distance,[59] while Leahy interpreted it as representing the patient's lack of capability to recognize a person.[54] Considered the most abstract cover, Eptitranxisticemestionscers Desending depicts an abstract mass, which some claim is a woman,[54] descending through a marble-like staircase. Hazelwood interpreted it as representing the patient's mind; although it once presented experiences, it is now unrecognizable.[10] Necrotomigaud presents an art board where blue tape hangs in the format of a square, reflecting the patient's emptiness in Stage 6.[23][54]

Seal's paintings and the Caretaker's music were featured in the 2019 French art exhibition Everywhere, an Empty Bliss by the company FRAC Auvergne, which featured pedagogical documents about their work and presented the names of the album covers.[57][58][60] The company later released a promotional video on YouTube, announcing that the exhibition would be held between 6 April and 6 June 2019.[61] Previously, Seal's paintings were also featured near one of Kirby's performances in the 2019 exhibition Cukuwruums.[53]

In 2018, when asked why the digital pages of the album presented the concept in detail but the physical packaging did not include text, Kirby said that Seal's paintings are important to each stage, and he was happy Seal allowed them to be used as the album covers. Writing of the overlap between their artistic visions, Kirby saw a correlation of works, as both "collide in a great way." He believed his descriptions may distract from this, as they are in digital form for listeners that "search a little deeper."[48]

Release and promotion

Kirby initially thought of not producing the series at all. Six months before the release of the first stage, he talked about it to other people, explaining he "wanted to be sure it didn't come across as this highbrow, pretentious idea."[1] The albums were released over three years: the first stage in 2016,[62][63] the next two in 2017,[64][65][66] the penultimate two in 2018,[67][68][69] and the final one in 2019.[70][71][72] According to Kirby, the delay between the releases was made to give a sense of time passing.[1] Although he expressed concern with dementia as a social problem, Kirby has said the disorder does not affect him "at a personal level", calling it "more of a fascination than a fear".[2][48][51] He noticed each experience with dementia as unique, asserting, "this version I've made is only unique to the Caretaker."[51] Kirby stated that his music has not been made available on Spotify due to the "constant devaluing of music by big business and streaming services."[73]

When releasing the first stage on 22 September 2016, Kirby announced the concept of the series,[74] stating that the albums would reveal "progression, loss and disintegration" as they fell "towards the abyss of complete memory loss". Some critics were confused by these statements;[75] Jordan Darville of The Fader wrote an article reporting that Kirby was diagnosed with early-onset dementia. Tiny Mix Tapes' Marvin Lin did the same, though both publications updated their posts when Kirby clarified the situation.[76][77] Kirby stated in an email to Pitchfork that he himself did not have dementia; only the Caretaker persona did. He added that there should not be any confusion and "it's not intentional if there is any."[75] In releasing Stage 5, Kirby's press release spoke about comparisons of the series' progression to the then-ongoing Brexit process.[78] The Caretaker's final record, released alongside Stage 6, was Everywhere, an Empty Bliss (2019), a compilation album of unused work.[79][80][81] While releasing Stage 6, Kirby noted and described the concept further.[14]

"When work began on this series it was difficult to predict how the music would unravel itself. Dementia is an emotive subject for many and always a subject I have treated with maximum respect.

Stages have all been artistic reflections of specific symptoms which can be common with the progression and advancement of the different forms of dementia.

Thanks always for your support of this series of works remembered by The Caretaker."[14]

— Leyland Kirby

Anonymous visual artist Weirdcore created music videos for the first two stages, both uploaded to Kirby's YouTube channel vvmtest.[82][83] Released in September 2016 and 2017, they have effects such as time-stretching and delay experimentations. He was known for creating visuals for ambient musician Aphex Twin.[84] Kirby said the visuals of Weirdcore are important to his music, calling them otherworldy.[48] In 2020, Weirdcore's visuals were presented with Kirby's music in a video titled "[−0º]";[85] it was chosen as one of the best audiovisual works of the year by Fact.[86] As of 10 March 2022, there are not any official uploads of music videos for the last four stages on vvmtest.[87]

In December 2017, Kirby performed at the Krakow Barbican for the Unsound Festival in Poland. His first show since 2011, it featured Seal's art, Weirdcore's visuals and Kirby drinking whisky.[88][89][90] The music videos would be presented throughout the Caretaker's following shows. Kirby was later featured at the Présences Électronique Festival in 2018,[91] where he played a coherent version of the 1944 song "Ce Soir" by singer Tino Rossi.[47] He participated in the "Solidarity" Unsound show in May 2019.[92] In 2020, he was due to perform live for the last time at the "[Re]setting" Rewire Festival, which would have occurred in April at The Hague in the Netherlands. However, the show was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[93][94] Kirby is expected to perform at the Primavera Sound festival in 2022.[95] Previously expressing hesitation to perform,[2] Kirby would now make each show be "a battle to make sense from the confusion". He mentioned that the visual art would explore the idea of making the public "feel ill."[51]

Critical reception

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Ondarock | 9/10 (Stage 1)[32] 8/10 (Stage 6)[45] |

| Pitchfork | 7.3/10 (Stage 1)[26] 7.9/10 (Stage 4)[24] |

| Resident Advisor | 4.3/5 (Stage 6)[23] |

| Tiny Mix Tapes | |

Everywhere at the End of Time received increasingly positive reactions as it progressed,[1][18] with Kirby expanding on the themes of An Empty Bliss.[13] In March 2021, it peaked as the best-selling record on Boomkat,[96] the platform Kirby uses for his physical releases.[5] As of 10 March 2022, it remains as one of Bandcamp's best-selling dark ambient records.[97] Initially, in what he called "today's culture of instant reaction", Kirby expected the public to say "it's just the same, he's just looping parts of big band records". He expressed opposition to these expected opinions; when releasing Stage 1, Kirby said "these parts have been looped for a specific reason [...] which will become clear down the line."[1]

The first three stages of the series were criticised for their portrayal of dementia. Pitchfork contributor Brian Howe expressed concern that the first stage may be a romanticised, if not exploitative, view of a mental illness. He found Kirby's description inaccurate; Howe "watched [his] grandmother succumb to it for a decade before she died, and it was very little like a 'beautiful daydream.' In fact, there was nothing aesthetic about it."[26] Pat Beane of Tiny Mix Tapes considered Stage 1 the most "pleasurable listen from [t]he Caretaker",[31] although Falisi regarded Stage 2 as neither "decay or beauty", "diagnosis or cure."[34] In 2021, Hazelwood described Stage 3 as Kirby's default "bag of tricks", but argued that these "are essential to the journey"; he followed this up by naming the first three stages "easily-digested", calling one's perception of time with them as "so fast. Almost too fast." In her opinion, "without those stages and their comforts, the transition into Stage 4 wouldn't have the crushing impact it does."[10]

The evocations of dementia in the last three stages were described by several critics as better, although some felt this was not the case. Bowe described Stage 4 as avoiding "a risk of pale romanticisation",[24] and Goldner felt that the record had "broken the loop", although he added that "Temporary Bliss State" is not "real dementia".[59] Falisi, writing about Goldner, was critical of Stage 5, considering the loop to be "unspooling (endlessly) off the capstans and piling up until new shapes form." He described the sound of the album as "the uncanny choke of absence", and argued, "If the thing is gone, why do I still feel it?"[40] Stage 6 received further praise, with characterisations ranging from "a mental descent rendered in agonizingly slow motion,"[23] to "something extra-ambient whose aches are of the cosmos."[44] Critics often described Stage 6 with additional praise, with one calling it a "jaw-dropping piece of sonic art" with "a unique force".[23][98]

Critics have also commented on the feelings given by the complete edition, with writers such as Dave Gurney of Tiny Mix Tapes citing it as disturbing.[99] More generally, it has been asserted that the work is depressing, with Hazelwood claiming that "the music of Everywhere sticks with you, its melodies haunting and infecting."[10] Luka Vukos, in his review for the blog HeadStuff, argued that the "empathy machine" of the series "is characterised not by words", and its acclaim "rests in [Kirby's] marrying of [the vinyl record] with the most contemporary modes of digital recall and manipulation."[3] Having written about some of Kirby's earlier music, Simon Reynolds said the Caretaker "could have renamed himself the Caregiver, for on this project he resembles a sonic nurse in a hospice for the terminally ill." In his opinion, "titles are heartbreaking and often describe the music more effectively than the reviewer ever could."[4]

Accolades

Everywhere at the End of Time appeared the most on year-end lists of The Quietus and Tiny Mix Tapes. Except for Stage 3, the latter reviewed each album and gave the first, fourth and sixth stages the "EUREKA!" award, usually given to albums that "explore the limits of noise and music" and are "worthy of careful consideration".[31][59][44] Resident Advisor included Stage 6 in its listing of "2019's Best Albums".[100] Quietus contributor Maria Perevedentseva chose "We Don't Have Many Days" as one of the best songs of 2016;[101] Stage 5 would later be included in the publication's listing of the best music in September 2018.[102] Stage 6 was named the website's "Lead Review" of the week and the best "miscellaneous" music release of 2019.[18][103]

| Album | Year | Publication | List | Rank | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | 2016 | The Quietus | Year-end | 16 | [104] |

| Tiny Mix Tapes | 35 | [105] | |||

| Stage 2 | 2017 | The Quietus | Semester-end | 88 | [106] |

| Stage 3 | Year-end | 39 | [107] | ||

| Stage 4 | 2018 | Tiny Mix Tapes | 26 | [108] | |

| The Quietus | Semester-end | 37 | [109] | ||

| Stage 5 | Year-end | 45 | [110] | ||

| Stage 6 | 2019 | Semester-end | 59 | [111] | |

| Obscure Sound | Year-end | 19 | [6] | ||

| Ondarock | 38 | [112] | |||

| Stages 1–6 | A Closer Listen | Decade-end | 4 | [113] | |

| Tiny Mix Tapes | 41 | [99] | |||

| Ondarock | 42 | [114] | |||

| Stages 4–6 | The Wire | Year-end | 35 | [115] |

Impact and popularity

Considered some of the best albums of the 2010s,[99][116] Everywhere at the End of Time is regarded by several critics and musicians as Kirby's magnum opus.[117][118][119] One reviewer singled out the two penultimate stages, the most ambient-driven ones, as making listeners reflect on the feeling of having dementia.[22] Conceptually, Everywhere also received acclaim: the portrayal of dementia was described by The Vinyl Factory as "remarkably emotive" and by Vogue's Corey Seymour as "life-changing",[8][120] with a Tiny Mix Tapes writer highlighting Stage 6 as "going fully corny in its final minutes".[121] Inspired by the Caretaker,[122] the fan-made 100-track album Memories Overlooked was released in 2017 by vaporwave musicians whose elder relatives had dementia.[15][123][124] Daily Record writer Darren McGarvey claimed he felt "struck by a deep sense of gratitude" after finishing the album, stating that is the "power of a proper piece of art,"[125] while author Cole Quinn titled Everywhere "the greatest album ever created."[28]

In 2020, users on the social media platform TikTok created a challenge to listen to the entire series in one sitting, due to its long length and, in the words of author Crew Bittner, "existential dread."[126][127] Kirby asserted he knew about the phenomenon by noting an exponential growth of views on the series' YouTube upload (21 million as of 10 March 2022);[5] only 12% of them came from the platform's algorithm, whereas direct searches made up over 50%.[116][128] In a video some writers hypothesised as the cause of Everywhere's popularity, YouTuber A Bucket of Jake called the series "the darkest album I have ever heard";[13][129] writing about the usage of music in education, author Emerson Slomka said that he was "particularly fascinated" by Jake's statement that "This is how you get someone interested in a topic, [for] every school in America."[130] Brian Browne, the president of Dementia Care Education, praised the attention given to the series, saying, "it produces the empathy that's needed."[12] Following its popularity, the series appeared often on Bandcamp's ambient recommendations, which Arielle Gordon of Bandcamp Daily attributed to the 'serene' deterioration of the stages.[131]

There were fictional creepypasta stories of the series shared on TikTok, with claims that it cures patients.[132] There were also claims that the series introduces symptoms of dementia in people; however, music has been proven to make patients happier.[12] The claims triggered a negative backlash from others, who felt this would turn the series into a meme and offend patients.[12][13][129] However, Kirby did not feel the challenge was offensive to the process of dementia.[116] He expressed a desire to be authentic while the record's popularity continued.[128] Everywhere was later called by TikTok a niche discovery and "unexpected hit" in a report for Variety.[133] Ultimately, Kirby saw the series as giving teenagers "an understanding into the symptoms a person with dementia may face."[116]

In 2021, the Vinyl Factory's Lazlo Rugoff found the TikTok phenomenon to draw "an unlikely audience" of teenagers to Kirby's music; he identified the record's popularity as their "vector for understanding dementia."[126] The same year would see Everywhere gain attention among the modding community of the rhythm game Friday Night Funkin' (2020), with the mod Everywhere at the End of Funk being described by Wren Romero of esports group Gamurs as "one of the most unique experiences of any FNF mod."[134]

Track listing

Adapted from Bandcamp.[14] Total lengths and notes adapted from Kirby's YouTube uploads of Stages 1–3,[82][83][135] Stages 4–6,[42][136][137] and the complete edition.[5]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "A1 – It's Just a Burning Memory" | 3:32 |

| 2. | "A2 – We Don't Have Many Days" | 3:30 |

| 3. | "A3 – Late Afternoon Drifting" | 3:35 |

| 4. | "A4 – Childishly Fresh Eyes" | 2:58 |

| 5. | "A5 – Slightly Bewildered" | 2:01 |

| 6. | "A6 – Things That Are Beautiful and Transient" | 4:34 |

| 7. | "B1 – All That Follows Is True" | 3:31 |

| 8. | "B2 – An Autumnal Equinox" | 2:46 |

| 9. | "B3 – Quiet Internal Rebellions" | 3:30 |

| 10. | "B4 – The Loves of My Entire Life" | 4:04 |

| 11. | "B5 – Into Each Others Eyes" | 4:36 |

| 12. | "B6 – My Heart Will Stop in Joy" | 2:41 |

| Total length: | 41:23 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 13. | "C1 – A Losing Battle Is Raging" | 4:37 |

| 14. | "C2 – Misplaced in Time" | 4:42 |

| 15. | "C3 – What Does It Matter How My Heart Breaks" | 2:37 |

| 16. | "C4 – Glimpses of Hope in Trying Times" | 4:43 |

| 17. | "C5 – Surrendering to Despair" | 5:03 |

| 18. | "D1 – I Still Feel As Though I Am Me" | 4:07 |

| 19. | "D2 – Quiet Dusk Coming Early" | 3:36 |

| 20. | "D3 – Last Moments of Pure Recall" | 3:52 |

| 21. | "D4 – Denial Unravelling" | 4:16 |

| 22. | "D5 – The Way Ahead Feels Lonely" | 4:15 |

| Total length: | 41:54 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 23. | "E1 – Back There Benjamin" | 4:14 |

| 24. | "E2 – And Heart Breaks" | 4:05 |

| 25. | "E3 – Hidden Sea Buried Deep" | 1:20 |

| 26. | "E4 – Libet's All Joyful Camaraderie" | 3:12 |

| 27. | "E5 – To the Minimal Great Hidden" | 1:41 |

| 28. | "E6 – Sublime Beyond Loss" | 2:10 |

| 29. | "E7 – Bewildered in Other Eyes" | 1:51 |

| 30. | "E8 – Long Term Dusk Glimpses" | 3:33 |

| 31. | "F1 – Gradations of Arms Length" | 1:31 |

| 32. | "F2 – Drifting Time Misplaced" (titled "Drifting Time Replaced" on Kirby's individual YouTube upload for Stage 3) | 4:15 |

| 33. | "F3 – Internal Bewildered World" | 3:29 |

| 34. | "F4 – Burning Despair Does Ache" | 2:37 |

| 35. | "F5 – Aching Cavern Without Lucidity" | 1:19 |

| 36. | "F6 – An Empty Bliss Beyond This World" | 3:36 |

| 37. | "F7 – Libet Delay" | 3:57 |

| 38. | "F8 – Mournful Cameraderie" | 2:39 |

| Total length: | 45:35 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 39. | "G1 – Post Awareness Confusions" | 22:09 |

| 40. | "H1 – Post Awareness Confusions" | 21:53 |

| 41. | "I1 – Temporary Bliss State" | 21:01 |

| 42. | "J1 – Post Awareness Confusions" | 22:16 |

| Total length: | 87:20 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 43. | "K1 – Advanced Plaque Entanglements" | 22:35 |

| 44. | "L1 – Advanced Plaque Entanglements" | 22:48 |

| 45. | "M1 – Synapse Retrogenesis" | 20:48 |

| 46. | "N1 – Sudden Time Regression into Isolation" | 22:08 |

| Total length: | 88:20 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 47. | "O1 – A Confusion So Thick You Forget Forgetting" | 21:52 |

| 48. | "P1 – A Brutal Bliss Beyond This Empty Defeat" | 21:36 |

| 49. | "Q1 – Long Decline Is Over" | 21:09 |

| 50. | "R1 – Place in the World Fades Away" | 21:19 |

| Total length: | 85:57 | |

Personnel

Credits adapted from YouTube.[5]

- Leyland Kirby – producer

- Ivan Seal – artwork

- Andreas Lubich – mastering

Release history

All released worldwide by record label History Always Favours the Winners.

| Date | Format | Catalog number | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 October 2017 |

|

HAFTWCD0103 | [138] |

| 7 April 2019 | Triple LP | HAFTW025026027-SET | [139] |

| 11 February 2021 | [140] | ||

| 21 May 2021?[lower-alpha 4] | [141] |

| Date | Format | Catalog number | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14 March 2019 |

|

HAFTWCD0406 | [142] |

| 23 September 2020 | [143] | ||

| 3 November 2021 | [144] | ||

| 3 January 2022 | [145] | ||

| 14 March 2019 | Sextuple LP | HAFTW028029030-SET | [146] |

| 7 April 2019 | [147] | ||

| 25 February 2021 | [148] | ||

| 28 May 2021 | [149] |

See also

- William Utermohlen, an artist with Alzheimer's disease who drew six self-portraits to chronicle the disorder's advancement

- Alzheimer's disease in the media

- Music therapy for Alzheimer's disease

- List of concept albums

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Doran, John (22 September 2016). "Interview | Out Of Time: Leyland James Kirby And The Death Of A Caretaker". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Parks, Andrew (17 October 2016). "Leyland Kirby on The Caretaker's New Project: Six Albums Exploring Dementia". Bandcamp Daily. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Vukos, Luka (22 June 2021). "Remembering | The Caretaker & Everywhere at the End Of Time". HeadStuff. Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- 1 2 Reynolds, Simon (June 2019). "Daring to decay, two hauntological guides call time on their longrunning projects". The Wire. No. 424. Exact Editions. p. 54, para. 5–6. Archived from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 vvmtest (14 March 2019). "The Caretaker – Everywhere At The End Of Time – Stages 1–6 (Complete)". YouTube. Archived from the original on 10 September 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- 1 2 Mineo, Mike (17 December 2019). "Best Albums of 2019: #20 to #11". Obscure Sound. sec. 19. The Caretaker – Everywhere at the End of Time – Stage 6. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ↑ Studarus, Laura (26 May 2017). "Big Ups: Sondre Lerche". Bandcamp Daily. sec. The Caretaker. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- 1 2 "The 10 best new vinyl releases this week". The Vinyl Factory. 18 March 2019. sec. The Caretaker – Everywhere at the end of time – Stage 6. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ↑ Falisi, Frank (8 December 2017). "2017: Superficial Temporal". Tiny Mix Tapes. sec. Dementia / Everywhere at the End of Time. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Hazelwood, Holly (18 January 2021). "Rediscover: The Caretaker: Everywhere at the End of Time". Spectrum Culture. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ↑ Beane, Pat; Scavo, Nick James (13 December 2016). "2016: A Musicology Of Exhaustion". Tiny Mix Tapes. p. 1, sec. Resting Face: Avatar OST. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Ezra, Marcus (23 October 2020). "Why Are TikTok Teens Listening to an Album About Dementia?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Garvey, Meaghan (22 October 2020). "What Happens When TikTok Looks To The Avant-Garde For A Challenge?". NPR. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kirby, Leyland James (22 September 2016). "Everywhere at the end of time". Bandcamp. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- 1 2 Bowe, Miles; Welsh, April Clare; Lobenfeld, Claire (6 December 2017). "The 20 best Bandcamp releases of 2017". Fact. sec. Various Artists – Memories Overlooked: A Tribute To The Caretaker. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ↑ Nove, Sarah (9 February 2021). "Everywhere at the End of Time: Art transcending aura". UWIRE. Retrieved 14 February 2022 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- ↑ Mitchell, Matt (11 October 2021). "I Feel As If I Might Be Vanishing: The Caretaker's An empty bliss beyond this World". Bandcamp Daily. para. 11. Archived from the original on 11 October 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "The Echoes Of Anxiety: The Caretaker's Final Chapter". The Quietus. 14 March 2019. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ↑ Colquhoun, Matt (15 March 2020). "Music Has The Right To Children: Reframing Mark Fisher's Hauntology". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ↑ Lore, Adrian Mark; Savage, Andrea (25 October 2016). "The Caretaker, Memory Loss and the End of Time The Suburbs': A Majestic Drive Down Memory Lane". UWIRE. Retrieved 14 February 2022 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- ↑ Nelson, Andy (3 May 2017). "Big Ups: Ceremony Pick Their Favorite Bands". Bandcamp Daily. sec. The Caretaker, Everywhere At The End Of Time. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 Otis, Erik. "Best of 2018: Releases". XLR8R. sec. The Caretaker Everywhere At The End of Time Stage 4 & 5. Archived from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ryce, Andrew (12 April 2019). "The Caretaker – Everywhere At The End Of Time (Stage 6) Album Review". Resident Advisor. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Bowe, Miles (26 April 2018). "The Caretaker: Everywhere at the End of Time – Stage 4 Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- 1 2 Padua, Pat (23 January 2017). "The Caretaker: Everywhere at the End of Time Music Review". Spectrum Culture. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- 1 2 3 Howe, Brian (7 October 2016). "The Caretaker: Everywhere at the End of Time Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ↑ Bowe, Miles (4 October 2016). "The Best Of Bandcamp: Odwalla88 is the best new band of the year". Fact. sec. The Caretaker – Everywhere At The End Of Time. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 Quinn, Cole (29 April 2021). "We found the greatest: Everywhere at the End of Time". UWIRE. Retrieved 14 February 2022 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- 1 2 3 Simpson, Paul. "Everywhere at the End of Time: Stages 1–3 - The Caretaker | Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ↑ Doran, John (7 October 2016). "The Best New Music You Missed In September". The Quietus. sec. The Caretaker – Everywhere at the End Of Time. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Beane, Pat (7 November 2016). "The Caretaker – Everywhere at the end of time | Music Review". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- 1 2 Palozzo, Michele (7 October 2016). "The Caretaker – Everywhere At The End Of Time :: Le Recensioni (Review)". Ondarock (in Italian). Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ↑ Beane, Pat (6 April 2017). "The Caretaker releases Stage 2 of his six-part series on dementia, Everywhere at the end of time". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Falisi, Frank (17 April 2017). "The Caretaker – Everywhere at the end of time – Stage 2 | Music Review". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ↑ Ryce, Andrew (6 April 2017). "The Caretaker releases Stage 2 of album series, Everywhere At The End Of Time". Resident Advisor. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ↑ Bowlly, Al (9 March 2015). "Heartaches". YouTube. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ Coral, Evan (3 July 2018). "2018: Second Quarter Favorites". Tiny Mix Tapes. p. 4, sec. The Caretaker – Everywhere at the end of time – Stage 4. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ Bowe, Miles (6 April 2018). "The Caretaker releases Mark Fisher tribute and Everywhere at the end of time: Stage Four". Fact. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ Pearl, Max (5 April 2018). "The Caretaker releases Stage 4 of album series, Everywhere At The End Of Time". Resident Advisor. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 Falisi, Frank (24 October 2018). "The Caretaker – Everywhere at the end of time – Stage 5 | Music Review". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 Simpson, Paul. "Everywhere at the End of Time: Stages 4–6 - The Caretaker | Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- 1 2 vvmtest (20 September 2018). "The Caretaker – Everywhere At The End Of Time – Stage 5 (FULL ALBUM)". YouTube. 19:11. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ↑ Ju, Esther (22 February 2021). "Casual Cadenza: Everywhere at the End of Time". UWIRE. Retrieved 14 February 2022 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Falisi, Frank (30 April 2019). "The Caretaker – Everywhere at the end of time – Stage 6 | Music Review". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- 1 2 Silvestri, Antonio (12 November 2019). "The Caretaker – Everywhere At The End Of Time – Stage 6 :: Le Recensioni (Review)". Ondarock (in Italian). Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ↑ Dunn, Parker (26 September 2020). "Everywhere at the End of Time Depicts the Horrors of Dementia Through Sound". UWIRE. Retrieved 14 February 2022 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- 1 2 Bazin, Alexandre (9 May 2018). "The Caretaker_PRESENCES électronique 2018". INA grm. 3:36. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021 – via YouTube.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bates, Landon (18 September 2018). "The Process: The Caretaker". The Believer. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ↑ Lubich, Andreas. "Loop_O". Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ↑ Lore, Adrian Mark (17 November 2017). "Where are they now? Where aren't they yet? Catching up with Leyland Kirby". UWIRE. Retrieved 14 February 2022 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Melfi, Daniel (7 October 2019). "Leyland James Kirby On The Caretaker, Alzheimer's Disease And His Show At Unsound Festival". Telekom Electronic Beats. Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- 1 2 Tan, Declan (10 March 2018). "The Noise In-Between: An Interview With Ivan Seal". The Quietus. para. 19. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 Battaglia, Andy (14 November 2019). "In Abandoned 14th-Century Building in Poland, a Painting Show Where the Art Aims to Disappear". ARTnews. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Leahy, Sydney (8 May 2021). "Everywhere at The End of Time". Teen Ink. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ↑ Noel, Jude (5 December 2019). "2010s: Favorite 50 Cover Art of the Decade". Tiny Mix Tapes. p. 5, sec. The Caretaker – Everywhere at the end of time. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ↑ Reid, Reed Scott (8 December 2016). "2016: Favorite Cover Art". Tiny Mix Tapes. sec. 17. The Caretaker – Everywhere at the end of time. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- 1 2 "IVAN SEAL / THE CARETAKER – everywhere, an empty bliss (DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE)" (PDF). FRAC Auvergne. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Ivan Seal / The Caretaker – everywhere, an empty bliss (DOSSIER DE PRESSE)" (PDF). FRAC Auvergne. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Goldner, Sam (30 April 2018). "The Caretaker – Everywhere at the end of time – Stage 4 | Music Review". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ↑ "IVAN SEAL / THE CARETAKER – Everywhere, an empty bliss". FRAC Auvergne. 6 April 2019. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ↑ fracauvergne (7 May 2019). "IVAN SEAL / THE CARETAKER – Everywhere, an empty bliss". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ↑ Bowe, Miles (22 September 2016). "The Caretaker to explore tragedy of memory loss with six album series over three years". Fact. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ Eede, Christian (6 April 2017). "The Caretaker's New Album Is Out Now". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ Bowe, Miles (28 September 2017). "Leyland James Kirby releases two new albums". Fact. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ↑ Lin, Marvin (Mr P) (28 September 2017). "The Caretaker releases Stage 3 of his six-album series on dementia, reveals 3xCD collector set". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ↑ Bowe, Miles (6 April 2017). "The Caretaker releases second installment of his six-part final album". Fact. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ↑ Lin, Marvin (Mr P) (20 September 2018). "The Caretaker releases Stage 5 of his six-album series on dementia, Everywhere at the end of time". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ↑ Clarke, Patrick (5 April 2018). "Phase Four Of The Caretaker's Everywhere At The End Of Time". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ↑ Lin, Marvin (Mr P) (5 April 2018). "The Caretaker releases Stage 4 of his six-album series on dementia, Everywhere at the end of time". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ↑ Otis, Erik (19 March 2019). "The Caretaker Drops Final Release, Everywhere At The End Of Time, Stage 6". XLR8R. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ↑ Ryce, Andrew (14 March 2019). "The Caretaker announces final release, Everywhere At The End Of Time Stage 6". Resident Advisor. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ↑ Lin, Marvin (Mr P) (14 March 2019). "The Caretaker releases final stage in his six-album series on dementia, Everywhere at the end of time". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ↑ Eede, Christian (28 September 2017). "The Caretaker Releases Two New Albums". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ Ryce, Andrew (22 September 2016). "The Caretaker returns with new album, Everywhere At The End Of Time". Resident Advisor. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- 1 2 Strauss, Matthew (22 September 2016). "James Leyland Kirby Gives 'The Caretaker' Alias Dementia, Releases First of Final 6 Albums". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ↑ Darville, Jordan (22 September 2016). "This Musician Is Recreating Dementia's Progression Over Three Years With Six Albums". The Fader. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ↑ Lin, Marvin (Mr P) (22 September 2016). "The Caretaker to release a six-part series exploring dementia over the course of three years". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ↑ Clarke, Patrick (20 September 2018). "Phase Five Of The Caretaker's Everywhere At The End Of Time". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ↑ Eede, Christian (14 March 2019). "The Caretaker Releases Project's Final Stage". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ↑ "Final release for The Caretaker project after 20 years". The Wire. 19 March 2019. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ↑ Bruce-Jones, Henry (14 March 2019). "The Caretaker bids farewell with Everywhere At The End Of Time: Stage 6". Fact. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- 1 2 vvmtest (22 September 2016). "The Caretaker – Everywhere at the end of time – Stage 1 (WEIRDCORE.TV)". YouTube. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- 1 2 vvmtest (17 September 2017). "The Caretaker – Everywhere at the end of time – Stage 2 (WEIRDCORE.TV)". YouTube. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ↑ Ryder, Jamie (18 August 2018). "Visual Overload: WEIRDCORE Discusses His Craft and Collaborators". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ↑ Bruce-Jones, Henry (15 June 2020). "Weirdcore trips through a chilly floral landscape in [−0º]". Fact. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ↑ "Fact 2020: Audiovisual". Fact. 24 December 2020. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ↑ vvmtest. "vvmtest". YouTube. Archived from the original on 14 January 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ↑ Eede, Christian (19 September 2017). "WATCH: New The Caretaker Teaser". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ Eede, Christian (19 July 2017). "Unsound Partner With The Barbican". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ↑ Murray, Eoin (18 December 2017). "Live Report: Unsound Dislocation at The Barbican". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ↑ Webb, Andy (19 March 2018). "The Caretaker to play live at Présences Électronique 2018". Resident Advisor. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ Philip, Ray (29 May 2019). "Unsound announces first acts for 2019 edition". Resident Advisor. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ↑ Hawthorn, Carlos (26 November 2019). "Rewire Festival confirms first acts for tenth anniversary in 2020". Resident Advisor. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ↑ Eede, Christian (26 November 2019). "Rewire Confirms First Acts For 2020". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ↑ "The Caretaker (UK)". Primavera Sound. 31 December 2019. Archived from the original on 26 June 2021. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ↑ Kirby, Leyland James. "Bestsellers". Boomkat. 01: Everywhere At The End Of Time (Vinyl Set). Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Kirby, Leyland James. "Dark Ambient Music & Artists". Bandcamp. sec. all-time best selling dark ambient: Everywhere at the end of time. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ↑ "Best of 2019: Releases". XLR8R. sec. The Caretaker Everywhere At The End Of Time, Stage 6. Archived from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 Gurney, Dave (19 December 2019). "2010s: Favorite 100 Music Releases of the Decade". Tiny Mix Tapes. p. 3, sec. 41. The Caretaker – Everywhere at the end of time. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ↑ "2019's Best Albums". Resident Advisor. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ↑ Perevedentseva, Maria (21 December 2016). "Tracks Of The Year 2016". The Quietus. The Caretaker – 'We Don't Have Many Days'. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ↑ Clarke, Patrick (5 October 2018). "Music Of The Month: Albums & Tracks We Loved This September". The Quietus. sec. The Caretaker – Everywhere At The End Of Time – Stage Five. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ↑ Clarke, Patrick (15 December 2019). "Reissues etc. Of The Year 2019 (In Association With Norman Records)". The Quietus. sec. 1. The Caretaker – Everywhere At The End Of Time. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ↑ Doran, John (19 December 2016). "Albums Of The Year 2016, In Association With Norman Records". The Quietus. sec. 16. The Caretaker – Everywhere at the End Of Time. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ↑ Scott, Jackson (14 December 2016). "2016: Favorite 50 Music Releases". Tiny Mix Tapes. p. 2, sec. 35. The Caretaker – Everywhere at the end of time. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ↑ Doran, John (3 July 2017). "The Best Albums Of 2017 Thus Far – And An Appeal For Help". The Quietus. sec. 88. The Caretaker – Everywhere at the End Of Time Stage Two. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ↑ "Albums Of The Year 2017, In Association With Norman Records". The Quietus. 23 December 2017. sec. 39. The Caretaker – Everywhere at the End Of Time – Stage 3. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ↑ A B D (17 December 2018). "2018: Favorite 50 Music Releases". Tiny Mix Tapes. p. 3, sec. 26. The Caretaker – Everywhere at the end of time – Stage 4. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ↑ Doran, John (30 July 2018). "Albums Of The Year So Far 2018: In Association With Norman Records". The Quietus. sec. 37. The Caretaker – Everywhere at the End Of Time – Stage IV. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ↑ Turner, Luke (25 December 2018). "Albums Of The Year 2018, In Association With Norman Records". The Quietus. sec. 45. The Caretaker – Everywhere at the End Of Time Stage V. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ↑ "Albums Of The Year So Far Chart 2019". The Quietus. 1 July 2019. 59. The Caretaker – Everywhere at the End Of Time (Stage 6). Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ↑ "I migliori dischi del 2019" [The best records of 2019]. Ondarock (in Italian). 38. The Caretaker – Everywhere At The End Of Time – Stage 6. Archived from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ↑ Dietz, Jason (2 December 2019). "Best of 2019: Music Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. A Closer Listen: 4. Everywhere at the end of time/everywhere, an empty bliss by The Caretaker. Archived from the original on 16 March 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ↑ "I migliori dischi del Decennio 10 (2010–2019)" [The best records of the 2010s]. Ondarock (in Italian). 42. The Caretaker – Everywhere At The End Of Time. Archived from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ↑ "Top 50 Releases 2019". The Wire. December 2019. 35: The Caretaker – Everywhere at the End Of Time (Stages 4–6). Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Clarke, Patrick (19 October 2020). "Everywhere At The End Of Time Becomes TikTok Challenge (Leyland James Kirby gives us his reaction)". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ↑ Elizabeth, Alker (20 May 2021). "Tunnels and Clearings at the End of Time". BBC Radio 3. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ↑ Hand, Richard J. (2018). "The Empty House: the Ghost of a Memory, the Memory of a Ghost" (PDF). University of East Anglia. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ↑ Chennington, Pad; Webster, James (22 September 2021). "A Deep Dive into The Caretaker's Everywhere at the End of Time". YouTube. 28:47. Archived from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ↑ Seymour, Corey (14 December 2018). "The Caretaker's Musical Project Is One Part Psychological Experiment, One Part Auditory Revelation". Vogue. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ↑ Rovinelli, Jessie Jeffrey Dunn (29 March 2019). "2019: First Quarter Favorites". Tiny Mix Tapes. p. 4, sec. The Caretaker – Everywhere at the end of time – Stage 6. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ Baird, Saxon (28 March 2018). "A Guide to the Diverse Cassette Scene of Santiago, Chile". Bandcamp Daily. para. 7. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ↑ Bowe, Miles (5 October 2017). "Artists pay tribute to The Caretaker on 100-track charity compilation Memories Overlooked". Fact. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- 1 2 Lin, Marvin (Mr P) (5 October 2017). "Nmesh curates 100-track tribute compilation to The Caretaker, proceeds to benefit The Alzheimer's Association". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- ↑ McGarvey, Darren (29 January 2021). "Dementia album proves power of art". Daily Record. MGN Ltd. Retrieved 14 February 2022 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- 1 2 Rugoff, Lazio (6 May 2021). "The Caretaker reissues An empty bliss beyond this world LP". The Vinyl Factory. para. 5. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ↑ Bittner, Crew; Tran, Vincent (30 October 2020). "Don't press skip: Music highlights you might have missed in October". UWIRE. Retrieved 14 February 2022 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- 1 2 Sinow, Catherine (26 November 2020). "How old, ambient Japanese music became a smash hit on YouTube". ArsTechnica. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- 1 2 Schroeder, Audra (19 October 2020). "TikTok turns The Caretaker's 6-hour song into a 'challenge'". Daily Dot. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ↑ Slomka, Emerson (2 November 2020). "Utilize music in education for better results". UWIRE. Retrieved 14 February 2022 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- ↑ Gordon, Arielle (30 October 2020). "The Best Ambient Music on Bandcamp: October 2020". Bandcamp Daily. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ Earp, Joseph (17 October 2020). "How An Obscure Six-Hour Ambient Record Is Terrifying A New Generation On TikTok". Junkee. Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ↑ Aswad, Jem (16 December 2020). "Inside TikTok's First Year-End Music Report". Variety. sec. Unexpected Hits and Niche Discoveries, Everywhere At The End Of The World. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ↑ Romero, Wren (9 August 2021). "The best mods for Friday Night Funkin'". Gamepur. Gamurs. sec. Everywhere At The End of Funk. Archived from the original on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- ↑ vvmtest (28 September 2017). "The Caretaker – Everywhere at the end of time – Stage 3 (FULL ALBUM)". YouTube. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ↑ vvmtest (5 April 2018). "The Caretaker – Everywhere At The End Of Time – Stage 4 (FULL ALBUM)". YouTube. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ↑ vvmtest (14 March 2019). "The Caretaker – Everywhere At The End Of Time – Stage 6 (FULL ALBUM)". YouTube. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ↑ Kirby, Leyland James (12 October 2017). "Everywhere At The End Of Time Stages 1–3". Boomkat. Archived from the original on 22 November 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Kirby, Leyland James (7 April 2019). "Everywhere At The End Of Time Stages 1–3 (Vinyl Set)". Boomkat. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Kirby, Leyland James (11 February 2021). "Everywhere At The End Of Time Stages 1–3 (Vinyl Set)". Boomkat. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Kirby, Leyland James (21 May 2021). "Everywhere At The End Of Time Stages 1–3 (Vinyl Set)". Boomkat. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Kirby, Leyland James (14 March 2019). "Everywhere At The End Of Time Stages 4–6 (4CD Set)". Boomkat. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Kirby, Leyland James (23 September 2020). "Everywhere At The End Of Time Stages 4–6 (4CD Set)". Boomkat. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Kirby, Leyland James (3 November 2021). "Everywhere At The End Of Time Stages 4–6 (4CD Set)". Boomkat. Archived from the original on 25 December 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Kirby, Leyland James (23 September 2020). "Everywhere At The End Of Time Stages 4–6 (4CD Set)". Boomkat. Archived from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Kirby, Leyland James (14 March 2019). "Everywhere At The End Of Time Stages 4–6 (Vinyl Set)". Boomkat. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Kirby, Leyland James (7 April 2019). "Everywhere At The End Of Time Stages 4–6 (Vinyl Set)". Boomkat. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Kirby, Leyland James (25 February 2021). "Everywhere At The End Of Time Stages 4–6 (Vinyl Set)". Boomkat. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Kirby, Leyland James (28 May 2021). "Everywhere At The End Of Time Stages 4–6 (Vinyl Set)". Boomkat. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

External links

- Everywhere at the End of Time at Discogs

- Everywhere at the End of Time at MusicBrainz

- #EverywhereAtTheEndOfTime on TikTok

.jpg.webp)