Fertility factor (demography)

Fertility factors are determinants of the number of children that an individual is likely to have. Fertility factors are mostly positive or negative correlations without certain causations.

Factors generally associated with increased fertility include the intention to have children,[1] in advanced societies very high gender equality,[1] religiosity,[2] inter-generational transmission of values,[1] marriage[3] and cohabitation,[4] maternal[5] and social[1] support, rural residence,[1] pro family government programs,[1] low IQ[6] and increased food production.[7]

Factors generally associated with decreased fertility include rising income,[1] value and attitude changes,[8][1] education,[1][9] female labor participation,[10] population control,[11] age,[12] contraception,[1] partner reluctance to having children,[1] very low level of gender equality,[1] infertility,[13] pollution,[14] and obesity,[15]

Factors associated with increased fertility

Intention

The predictive power of intentions continues to be debated. Research that argues that intentions are a good predictor of actual results tends to draw ideas from the theory of planned behavior (TPB). According to the TPB, intentions stem from three factors: attitudes regarding children, including the cost of raising them versus perceived benefits; subjective norms, for example the influence of others; and perceived control over behavior, that is, how much control an individual has over their own behavior.[1]

Fertility intentions tend to boil down to quantum intentions, or how many children to bear, and tempo intentions, meaning when to have them. Of these, quantum intention is the poor predictor because it tends to change as a result of the ups and downs of a typical life. Tempo intention is a somewhat better predictor, but still a weak way to predict actual results.[1]

The intention to have children generally increases the probability of having children. This relation is well evidenced in advanced societies, where birth control is the default option.[1]

A comparison of a survey to birth registers in Norway found that parents were more likely to realize their fertility intentions than childless respondents.[16] It was also suggested that childless individuals may underestimate the effort of having children.[16] On the other hand, parents may better understand their ability to manage another child.[16] Individuals intending to have children immediately are more likely to achieve this within two years,[16] whereas in contrast, the fertility rate was found to be higher among those intending to have children in the long term (after four years).[16] Stability of fertility intentions further improves the chance to realize them.[17] Such stability is increased by the belief that having a child will improve life satisfaction and partner relationships.[17]

Chances of realizing fertility intentions are lower in post-Soviet states than in Western European states.[18]

There are many determinants of the intention to have children, including:

- The mother's preference of family size, which influences that of the children through early adulthood.[19] Likewise, the extended family influences fertility intentions, with an increased number of nephews and nieces increasing the preferred number of children.[1]

- Social pressure from kin and friends to have another child.[1]

- Social support. A study from West Germany found that both men receiving no support at all and receiving support from many different people have a lower probability of intending to have another child than those with a moderate degree of support. The negative effect of support from many different people is probably related to coordination problems.[1]

- Happiness, with happier people tending to want more children.[1]

- A secure housing situation.[20]

- Religiosity.[21]

Very high level of gender equality

In advanced societies, in which birth control is the default option, a more equal division of household tasks tends to improve chances for a second child.[1] Equally, increases in employment equity tend to lead to a more equal division of household labor, and thus improve chances for a second child.[1]

Fertility preference

The Preference Theory suggests that a woman's attitudes towards having children are shaped early in life. Furthermore, these attitudes tend to hold across the life course, and boil down to three main types: career-oriented, family-oriented, and a combination of both work and family. Research shows that family-oriented women have the most children, and work-oriented women have the least, or none at all, although causality remains unclear.[1]

Preferences can also apply to the sex of the children born, and can therefore influence the decisions to have more children. For instance, if a couple's preference is to have at least one boy and one girl, and the first two children born are boys, there is a significantly high likelihood that the couple will opt to have another child.[1]

Religiosity

A survey taken place in 2002 in the United States found that women who reported religion as "very important" in their everyday lives had a higher fertility than those reporting it as "somewhat important" or "not important".[2]

For many religions, religiosity is directly associated with an increase in the intention to have children.[2] This appears to be the main means by which religion increases fertility.[21] For example, as of 1963, Catholic couples generally had intentions to have more children than Jewish couples, who in turn, tended to have more children than Protestant couples.[21] Among Catholics, increased religiosity is associated with the intention to have more children, while on the other hand, increased religiousness among Protestants is associated with the intention to have fewer children.[21]

It has also been suggested that religions generally encourage lifestyles with fertility factors that, in turn, increase fertility.[22] For example, religious views on birth control are, in many religions, more restrictive than secular views, and such religious restrictions have been associated with increased fertility.[23]

Religion sometimes modifies the fertility effects of education and income. Catholic education at the university level and the secondary school level is associated with higher fertility, even when accounting for the confounding effect that higher religiosity leads to a higher probability of attending a religiously affiliated school.[21] Higher income is also associated with slightly increased fertility among Catholic couples, however, is associated with slightly decreased fertility among Protestant couples.[21]

Parents' religiosity is positively associated with their children's fertility. Therefore, more religious parents will tend to increase fertility.[1]

A 2020 study found that the relation between religiosity and fertility was driven by the lower aggregate fertility of secular individuals. While religiosity did not prevent low fertility levels (as some highly religious countries had low fertility rates), secularism did prevent high fertility (as no highly secular country had high fertility rates). Societal level secularism was also a better predictor of religious individuals' fertility than secular individuals, largely due to the effects of cultural values on reproduction, gender and personal autonomy.[24]

Intergenerational transmission of values

The transmission of values from parents to offspring (nurture) has been a core area of fertility research. The assumption is that parents transmit these family values, preferences, attitudes and religiosity to their children, all of which have long-term effects analogous to genetics. Researchers have tried to find a causal relationship between, for example, the number of parents' siblings and the number of children born by the parents own children (a quantum effect), or between the age of the first birth of the parents' generation and age of first birth of any of their own children (a tempo effect).[1]

Most studies concerning tempo focus on teenage mothers and show that having had a young mother increases the likelihood of having a child at a young age.[1]

In high-income countries, the number of children a person has strongly correlates with the number of children that each of those children will eventually have.[25][1]

Danish data from non-identical twins growing up in the same environment compared to identical twins indicated that genetic influences in themselves largely override previously shared environmental influences.[1] The birth order does not seem to have any effect on fertility.[21]

Other studies, however, show that this effect can be balanced by the child's own attitudes that result from personal experiences, religiosity, education, etc. So, although the mother's preference of family size may influence that of the children through early adulthood,[25] the child's own attitudes then take over and influence fertility decisions.[1]

Marriage and cohabitation

The effect of cohabitation on fertility varies across countries.[1]

In the US cohabitation is generally associated with lower fertility.[1] However, another study found that cohabiting couples in France have equal fertility as married ones.[1] Russians have also been shown to have a higher fertility within cohabitation.[26]

Survey data from 2003 in Romania showed that marriage equalized the total fertility rate among both highly educated and limited-education people to approximately 1.4. Among those cohabiting, on the other hand, a lower level of education increased the fertility rate to 1.7, and a higher level of education decreased it to 0.7.[27] Another study found that Romanian women with little education have about equal fertility in marital and cohabiting partnerships.[28]

A study of the United States, and multiple countries in Europe, found that women who continue to cohabit after giving birth have a significantly lower probability of having a second child than married women in all countries, except those in Eastern Europe.[29]

Maternal support

Data from the Generations and Gender Survey showed that women with living mothers had earlier first births, while a mother's death early in a daughter's life correlated with a higher probability of childlessness. On the other hand, the survival of fathers had no effect on either outcome. Co-residence with parents delayed first births and resulted in lower total fertility and higher probability of childlessness. This effect is even stronger for poor women.[5]

Social support

Social support from the extended family and friends can help a couple decide to have a child, or another one.

Studies mainly in ex-communist Eastern European countries have associated increased fertility with increased social capital in the form of personal relationships, goods, information, money, work capacity, influence, power, and personal help from others.[1]

Research in the U.S. shows that the extended family willing to provide support becomes a "safety net". This is particularly important for single mothers and situations involving partnership instability.[1]

Rural residence

Total fertility rates are higher among women in rural areas than among women in urban areas, as evidenced from low-income,[30] middle-income[30] and high-income countries.[1] Field researchers have found that fertility rates are high and remain relatively stable among rural populations. Little evidence exists to suggest that high-fertility parents appear to be economically disadvantaged, further strengthening the fact that total fertility rates tend to be higher among women in rural areas.[31] On the other hand, studies have suggested that a higher population density is associated with decreased fertility rates.[32] It is shown through studies that fertility rates differ between regions in ways that reflect the opportunity costs of child rearing. In a region with high population density, women restrain themselves from having many children due to the costs of living, therefore lowering the fertility rates.[32] Within urban areas, people in suburbs are consistently found to have higher fertility.[1] Some research indicates that population density may explain up to 31% of the variance in fertility rates, although the effect of population density on fertility can be moderated by other factors such as environmental conditions, religiosity and social norms.[33]

Pro-family government programs

Many studies have attempted to determine the causal link between government policies and fertility. However, as this article suggests, there are many factors that can potentially affect decisions to have children, how many to have, and when to have them, and separating these factors from effects of a particular government policy is difficult. Making this even more difficult is the time lag between government policy initiation and results.[1]

The purpose of these programs is to reduce the opportunity cost of having children, either by increasing family income or reducing the cost of children.[8] One study has found a positive effect on number of children during life due to family policy programs that make it easier for women to combine family and employment. Again, the idea here is to reduce the opportunity cost of children. These positive results have been found in Germany, Sweden, Canada, and the U.S.[34]

However, other empirical studies show that these programs are expensive and their impact tends to be small, so currently there is no broad consensus on their effectiveness in raising fertility.[4]

Other factors associated with increased fertility

Other factors associated with increase of fertility include:

- Social pressure: Women have an increased probability to have another child when there is social pressure from parents, relatives, and friends to do so.[1] For example, fertility increases during the one to two years after a sibling or a co-worker has a child.[1]

- Patriarchy: Male-dominated families generally have more children.[21]

- Nuclear family households have higher fertility than cooperative living arrangements, according to studies both from the Western World.[1]

- Illegalization of abortion temporarily increased birth rates in communist Romania for a few years, but this was followed by a later decline due to an increased use of illegal abortion.[8]

- Immigration sometimes increases fertility rates of a country because of the births to the immigrant groups.[35] However, over succeeding generations, migrant fertility often converges to that of their new country.[1]

- Assisted reproduction technology (ART). One study from Denmark projects an increase in fertility, as a result of ART, that could increase the 1975 birth cohort by 5%.[1] In addition, ART seems to challenge the biological limits of successful childbearing.[1] ·

- Homophily: an increased fertility is seen in people with a tendency to seek acquaintance among those with common characteristics.[4]

Factors associated with decreased fertility

Fertility is declining in advanced societies because couples are having fewer children or none at all, or they are delaying childbirth beyond the woman's most fertile years. The factors that lead to this trend are complex and probably vary from country to country.[8]

Rising income

Increased income and human development are generally associated with decreased fertility rates.[38] Economic theories about declining fertility postulate that people earning more have a higher opportunity cost if they focus on childbirth and parenting rather than continuing their careers,[1] that women who can economically sustain themselves have less incentive to become married,[1] and that higher income parents value quality over quantity and so spend their resources on fewer children.[1]

On the other hand, there is some evidence that with rising economic development, fertility rates drop at first, but then begin to rise again as the level of social and economic development increases, while still remaining below the replacement rate.[39][40]

Value and attitude changes

While some researchers cite economic factors as the main driver of fertility decline, socio-cultural theories focus on changes in values and attitudes toward children as being primarily responsible. For example, the Second Demographic Transition reflects changes in personal goals, religious preferences, relationships, and perhaps most important, family formations.[8] Also, Preference Theory attempts to explain how women's choices regarding work versus family have changed and how the expansion of options and the freedom to choose the option that seems best for them are the keys to recent declines in TFR.[8]

A comparative study in Europe found that family-oriented women had the most children, work-oriented women had fewer or no children, and that among other factors, preferences play a major role in deciding to remain childless.[1]

Another example of this can be found in Europe and in post-Soviet states, where values of increased autonomy and independence have been associated with decreased fertility.[1]

Education

Results from research which attempts to find causality between education and fertility is mixed.[1] One theory holds that higher educated women are more likely to become career women. Also, for higher educated women, there is a higher opportunity cost to bearing children. Both would lead higher educated women to postpone marriage and births.[1] However, other studies suggest that, although higher educated women may postpone marriage and births, they can recuperate at a later age so that the impact of higher education is negligible.[1]

In the United States, a large survey found that women with a bachelor's degree or higher had an average of 1.1 children, while those with no high school diploma or equivalent had an average of 2.5 children.[3] For men with the same levels of education, the number of children was 1.0 and 1.7, respectively.[3]

In Europe, on the other hand, women who are more educated eventually have about as many children as do the less educated, but that education results in having children at an older age.[1] Likewise, a study in Norway found that better-educated males have a decreased probability of remaining childless, although they generally became fathers at an older age.[41]

Catholic education at the university level and, to a lesser degree, at the secondary school level, is associated with higher fertility, even when accounting for the confounding effect that higher religiosity among Catholics leads to a higher probability of attending a religiously affiliated school.[21]

The level of a country's development often determines the level of women's education required to affect fertility. Countries with lower levels of development and gender equivalence are likely to find that a higher level of women's education, greater than secondary level, is required to affect fertility. Studies suggest that in many sub-Saharan African countries fertility decline is linked to female education.[42][43] Having said this, fertility in undeveloped countries can still be significantly reduced in the absence of any improvement in the general level of formal education. For example, During the period 1997-2002 (15 years), fertility in Bangladesh fell by almost 40 per cent, despite the fact that literacy rates (especially those of women) did not increase significantly. This reduction has been attributed to that country's family planning program, which could be called a form of informal education.[44]

Population control

China and India have the oldest and the largest human population control programs in the world.[45] In China, a one-child policy was introduced between 1978 and 1980,[46] and began to be formally phased out in 2015 in favor of a two-child policy.[47] The fertility rate in China fell from 2.8 births per woman in 1979 to 1.5 in 2010.[11] However, the efficacy of the one-child policy itself is not clear, since there was already a sharp reduction from more than five births per woman in the early 1970s, before the introduction of the one-child policy.[11] It has thereby been suggested that a decline in fertility rate would have continued even without the strict antinatalist policy.[48] As of 2015, China has ended its decade long one child police allowing couples to have two children. This was a result of China having a large dependency ratio with its ageing population and working force.[49]

Extensive efforts have been put into family planning in India. The fertility rate has dropped from 5.7 in 1966 to 2.4 in 2016.[50][51] Still, India's family planning program has been regarded as only partially successful in controlling fertility rates.[52]

Female labor force participation

Increased participation of women in the workforce is associated with decreased fertility. A multi-country panel study found this effect to be strongest among women aged 20–39, with a less strong but persistent effect among older women as well.[10] International United Nations data suggests that women who work because of economic necessity have higher fertility than those who work because they want to do so.[53]

However, for countries in the OECD area, increased female labor participation has been associated with increased fertility.[54]

Causality analyses indicate that fertility rate influences female labor participation, not the other way around.[1]

Women who work in nurturing professions such as teaching and health generally have children at an earlier age.[1] It is theorized that women often self-select themselves into jobs with a favorable work–life balance in order to pursue both motherhood and employment.[1]

Age

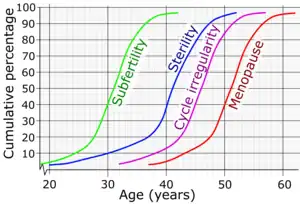

Regarding age and female fertility, fertility starts at onset of menses, typically around age 12-13[55][56][57] Most women become subfertile during the early 30s, and during the early 40s most women become sterile.[12]

Regarding age and male fertility, men have decreased pregnancy rates, increased time to pregnancy, and increased infertility as they age, although the correlation is not as substantial as in women.[58] When controlling for the age of the female partner, comparisons between men under 30 and men over 50 found relative decreases in pregnancy rates between 23% and 38%.[58]

An Indian study found that couples where the woman is less than one year younger than the man have a total mean number of children of 3.1, compared to 3.5 when the woman is 7–9 years younger than the man.[59]

Contraception

The "contraceptive revolution" has played a crucial role in reducing the number of children (quantum) and postponing child-bearing (tempo).[1]

Periods of decreased use of contraceptive pills due to fears of side effects have been linked with increased fertility in the United Kingdom.[1] Introductions of laws that increase access to contraceptives have been associated with decreased fertility in the United States.[1] However, short-term decreases in fertility may reflect a tempo effect of later childbearing, with individuals using contraceptives catching up later in life. A review of long-term fertility in Europe did not find fertility rates to be directly affected by availability of contraceptives.[8]

Partner and partnership

The decision to bear a child in advanced societies generally requires agreement between both partners. Disagreement between partners may mean that the desire for children of one partner are not realized.[1]

The last several decades have also seen changes in partnership dynamics. This has led to a tendency toward later marriages and a rise in unmarried cohabitation. Both of these have been linked to the postponement of parenthood (tempo) and thus reduced fertility.[1]

Very low level of gender equality

The effects differed across countries.[1] A study comparing gender equality in the Netherlands with that of Italy found that an unequal division of household work can significantly reduce a woman's interest in having children.[1]

Another study focused on quality of life of women in Canada found that women who felt overburdened at home tended to have fewer children.[1]

Another study found a U-shaped relationship between gender equity within the couple and fertility with higher probability of having a second child in families with either very low or very high gender equality.[1]

Infertility

20-30% percent of infertility cases are due to male infertility, 20–35% are due to female infertility, and 25-40% are due to combined problems.[13] In 10–20% of cases, no cause is found.[13]

The most common cause of female infertility is ovulatory problems, which generally manifest themselves by sparse or absent menstrual periods.[60] Male infertility is most commonly caused by deficiencies in the semen: semen quality is used as a surrogate measure of male fecundity.[61]

Other factors associated with decreased fertility

- Intense relationships. A Dutch study found that couples are likely to have fewer children if they have high levels of either negative or positive interaction.[62]

- Unstable relationships, according to a review in Europe.[8]

- Higher tax rates.[1]

- Unemployment. A study in the USA shows that unemployment in women has effects both in the short and the long term in reducing their fertility rate.[63]

- Generosity of public pensions. It has been theorized that social security systems decrease the incentive to have children to provide security in old age.[1]

Factors of no or uncertain effect

Delayed childbearing

The trend of couples forming partnerships and marrying at later ages has been going on for some time. For example, in the US, during the period 1970 to 2006, the average age of first-time mothers increased by 3.6 years, from 21.4 years to 25.0 years.[64]

Also, fertility postponement has become common in all European countries, including those of the former Soviet Union.[65]

Nevertheless, delayed childbirth alone is not sufficient to reduce fertility rates: in France despite the average high age at first birth, fertility rate remains close to the 2.1 replacement value.[8] The aggregate effects of delayed childbearing tend to be relatively minor, because most women still have their first child well before the onset of infertility.[65]

Intelligence

The relationship between fertility and intelligence has been investigated in many demographic studies; there is no conclusive evidence of a positive or negative correlation between human intelligence and fertility rate.[66]

Other factors of no or uncertain effect

The following have been reported, at least in the primary research literature, to have no or uncertain effects.

- Personality. One study found no consequential associations between personality and fertility, with tested traits including anxiety, nurturance needs, delayed gratification, self-awareness, compulsiveness, ambiguity tolerance, cooperativeness, and need for achievement.[21]

- Government support of assisted reproductive technology, policies that transfer cash to families for pregnancy, and child support have only a limited effect on total fertility rate, according to the same review.[8]

- Relationship quality and stability have complex relations to fertility, wherein couples with a medium-quality relationship appear to be the most likely to have another child.[1]

- Governmental maternity leave benefits have no significant effect on fertility, according to one primary source.[67]

- Children from previous unions. A study in the United Kingdom found that partners with children from previous unions have a higher likelihood of having children together.[1] A study in France found the opposite, that childbearing rates are lowest after repartnering if both partners are already parents.[68] The French study also found that in couples where only one was already a parent, fertility rates were about the same as in childless couples.[68]

- Spousal height difference.[69]

- Mother's health is also a great determinant of the state of health of the unborn child, mother's death in childbirth means almost certain death for her newly born child.[70]

- Birth spacing refers to the timing and frequency of pregnancies. Child birth to a mother is affected by this factor in one way or the other.[70]

- Familism. The fertility impact is unknown in country-level familism systems, where the majority of the economic and caring responsibilities rest on the family (such as in Southern Europe), as opposed to defamilialized systems, where welfare and caring responsibilities are largely supported by the state (such as Nordic countries).[1]

Racial and ethnic factors

In the United States, Hispanics, and African Americans have earlier and higher fertility than other racial and ethnic groups. In 2009, the teen birth rate for Hispanics between the age 15-19 was roughly 80 births per 1000 women. The teen birth rate for African Americans in 2009 was 60 births per 1000 women and 20 for non Hispanic teens (white).[71] According to the United States census, State Health Serve and the CDC, Hispanics accounted for 23% of the birth in 2014 out of the 1,000,000 births in the United States.[72][3]

Multifactorial analyses

A regression analysis on a population in India resulted in the following equation of total fertility rate, where parameters preceded by a plus were associated with increased fertility, and parameters preceded by a minus were associated with decreased fertility:[38]

Total Fertility Rate = 0.02 (human development index*) + 0.07 (infant mortality rate*) − 0.34 (contraceptive use) + 0.03 (male age at marriage*) − 0.21 (female age at marriage) − 0.16 (birth interval) − 0.26 (use of improved water quality) + 0.03 (male literacy rate*) − 0.01 (female literacy rate*) − 0.30 (maternal care)

* = Parameter did not reach statistical significance on its own

See also

- Family § Size

- List of people with the most children

- Natalism and antinatalism, promoting and opposing human reproduction

- Sub-replacement fertility

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 Balbo N, Billari FC, Mills M (February 2013). "Fertility in Advanced Societies: A Review of Research: La fécondité dans les sociétés avancées: un examen des recherches". European Journal of Population. 29 (1): 1–38. doi:10.1007/s10680-012-9277-y. PMC 3576563. PMID 23440941.

- 1 2 3 Hayford SR, Morgan SP (2008). "Religiosity and Fertility in the United States: The Role of Fertility Intentions". Social Forces; A Scientific Medium of Social Study and Interpretation. 86 (3): 1163–1188. doi:10.1353/sof.0.0000. PMC 2723861. PMID 19672317.

- 1 2 3 4 Martinez G, Daniels K, Chandra A (April 2012). "Fertility of men and women aged 15-44 years in the United States: National Survey of Family Growth, 2006-2010" (primary research report). National Health Statistics Reports. Division of Vital Statistics, National Center for Health Statistics (51): 1–28. PMID 22803225. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-04-23. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- 1 2 3 Fent T, Diaz BA, Prskawetz A (2013). "Family policies in the context of low fertility and social structure". Demographic Research. 29 (37): 963–998. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2013.29.37.

- 1 2 Schaffnit SB, Sear R (2014). "Wealth modifies relationships between kin and women's fertility in high-income countries". Behavioral Ecology. 25 (4): 834–842. doi:10.1093/beheco/aru059. ISSN 1045-2249.

- ↑ Shatz SM (March 2008). "IQ and fertility: A cross-national study". Intelligence. 36 (2): 109–111. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2007.03.002.

- ↑ "Human population numbers as a function of food supply" (PDF). Russel Hopfenburg, David Pimentel, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA;2Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-09-26. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 The ESHRE Capri Workshop Group (2010). "Europe the continent with the lowest fertility" (review). Human Reproduction Update. 16 (6): 590–602. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq023. PMID 20603286.

- ↑ Pradhan E (2015-11-24). "Female Education and Childbearing: A Closer Look at the Data". Investing in Health. Archived from the original on 2019-07-28. Retrieved 2019-03-11.

- 1 2 Bloom D, Canning D, Fink G, Finlay J (2009). "Fertility, female labor force participation, and the demographic dividend". Journal of Economic Growth. 14 (2): 79–101. doi:10.1007/s10887-009-9039-9.

- 1 2 3 Feng W, Yong C, Gu B (2012). "Population, Policy, and Politics: How Will History Judge China's One-Child Policy?" (PDF). Population and Development Review. 38: 115–29. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00555.x. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-06-06. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- 1 2 3 te Velde ER, Pearson PL (2002). "The variability of female reproductive ageing". Human Reproduction Update. 8 (2): 141–54. doi:10.1093/humupd/8.2.141. PMID 12099629.

- 1 2 3 "ART fact sheet (July 2014)". European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "Exposure to air pollution seems to negatively affect women's fertility". Archived from the original on 2021-12-14. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ↑ Dağ ZÖ, Dilbaz B (1 June 2015). "Impact of obesity on infertility in women". Journal of the Turkish German Gynecological Association. 16 (2): 111–7. doi:10.5152/jtgga.2015.15232. PMC 4456969. PMID 26097395.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dommermuth L, Klobas J, Lappegård T (2014). "Differences in childbearing by time frame of fertility intention. A study using survey and register data from Norway". Archived from the original on 2017-07-04. Retrieved 2022-06-12. Part of the research project Family Dynamics, Fertility Choices and Family Policy (FAMDYN)

- 1 2 Cavalli L, Klobas J (2013). "How expected life and partner satisfaction affect women's fertility outcomes: the role of uncertainty in intentions". Population Review. 52 (2). Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2022-07-12.

- ↑ Spéder Z, Kapitány B (2014). "Failure to Realize Fertility Intentions: A Key Aspect of the Post-communist Fertility Transition". Population Research and Policy Review. 33 (3): 393–418. doi:10.1007/s11113-013-9313-6. S2CID 154279339.

- ↑ Axinn WG, Clarkberg ME, Thornton A (February 1994). "Family influences on family size preferences". Demography. 31 (1): 65–79. doi:10.2307/2061908. JSTOR 2061908. PMID 8005343.

- ↑ Vignoli D, Rinesi F, Mussino E (2013). "A home to plan the first child? Fertility intentions and housing conditions in Italy" (PDF). Population, Space and Place. 19: 60–71. doi:10.1002/psp.1716. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-22. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Westoff CF, Potter RG (1963). Third Child: A Study in the Prediction of Fertility. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400876426. Pages 238-244 Archived 2021-05-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Page 118 Archived 2021-04-27 at the Wayback Machine in: Zhang L (2010). Male Fertility Patterns and Determinants. Volume 27 of The Springer Series on Demographic Methods and Population Analysis. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9789048189397.

- ↑ Schenker JG, Rabenou V (June 1993). "Family planning: cultural and religious perspectives". Human Reproduction. 8 (6): 969–76. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138176. PMID 8345093.

- ↑ Schnabel, Landon. 2016. "Secularism and Fertility Worldwide". SocArXiv. July 19. doi:10.31235/osf.io/pvwpy.

- 1 2 Murphy M (2013). "Cross-national patterns of intergenerational continuities in childbearing in developed countries". Biodemography and Social Biology. 59 (2): 101–26. doi:10.1080/19485565.2013.833779. PMC 4160295. PMID 24215254.

- ↑ Potârcă G, Mills M, Lesnard L (2013). "Family Formation Trajectories in Romania, the Russian Federation and France: Towards the Second Demographic Transition?". European Journal of Population. 29: 69–101. doi:10.1007/s10680-012-9279-9. S2CID 3270388. Archived from the original on 2019-12-10. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ↑ Hoem JM, Mureşan C, Hărăguş M (2013). "Recent Features of Cohabitational and Marital Fertility in Romania" (PDF). Population English Edition. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-12-01. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ↑ Hoem JM, Muresan C (2011). "The Role of Consensual Unions in Romanian Total Fertility". Stockholm Research Reports in Demography. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-02-20.

- ↑ Perelli-Harris B (2014). "How Similar are Cohabiting and Married Parents? Second Conception Risks by Union Type in the United States and Across Europe". European Journal of Population. 30 (4): 437–464. doi:10.1007/s10680-014-9320-2. PMC 4221046. PMID 25395696.

- 1 2 Global Monitoring Report 2015/2016: Development Goals in an Era of Demographic Change. World Bank Publications. 2015. ISBN 9781464806704. Page 148 Archived 2021-05-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Caldwell JC (March 1977). "The economic rationality of high fertility: An investigation illustrated with Nigerian survey data". Population Studies. 31 (1): 5–27. doi:10.1080/00324728.1977.10412744. PMID 22070234.

- 1 2 Sato Y (30 July 2006), "Economic geography, fertility and migration" (PDF), Journal of Urban Economics, archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2016, retrieved 31 March 2008

- ↑ Rotella, Amanda, Michael EW Varnum, Oliver Sng, and Igor Grossmann. "Increasing population densities predict decreasing fertility rates over time: A 174-nation investigation." (2020).

- ↑ Balbo 2013 Archived 2022-07-14 at the Wayback Machine (see top of list), citing: Kalwij A (May 2010). "The impact of family policy expenditure on fertility in western Europe". Demography. 47 (2): 503–19. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0104. PMC 3000017. PMID 20608108.

- ↑ "Birth Rates Rising in Some Low Birth-Rate Countries". www.prb.org. Archived from the original on 2017-03-30. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ↑ "Field Listing: Total Fertility Rate". The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 2013-08-11. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

- ↑ "Country Comparison: GDP - Per Capita (PPP)". The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 2016-04-24. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

- 1 2 Rai PK, Pareek S, Joshi H (2013). "Regression Analysis of Collinear Data using r-k Class Estimator: Socio-Economic and Demographic Factors Affecting the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) in India" (primary research article). Journal of Data Science. 11: 323–342. doi:10.6339/JDS.2013.11(2).1030. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 November 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ↑ "The best of all possible worlds? A link between wealth and breeding". The Economist. August 6, 2009. Archived from the original on February 7, 2018. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ↑ Myrskylä M, Kohler HP, Billari FC (August 2009). "Advances in development reverse fertility declines". Nature. 460 (7256): 741–3. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..741M. doi:10.1038/nature08230. PMID 19661915. S2CID 4381880.

- ↑ Rindfuss RR, Kravdal O (2008). "Changing Relationships between Education and Fertility: A Study of Women and Men Born 1940 to 1964" (PDF). American Sociological Review. 73 (5): 854–873. doi:10.1177/000312240807300508. hdl:10419/63098. ISSN 0003-1224. S2CID 56286073. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-08. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ↑ Kebede E, Goujon A, Lutz W (February 2019). "Stalls in Africa's fertility decline partly result from disruptions in female education". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (8): 2891–2896. doi:10.1073/pnas.1717288116. PMC 6386713. PMID 30718411.

- ↑ Pradhan E (2015-11-24). "Female Education and Childbearing: A Closer Look at the Data". Investing in Health. Archived from the original on 2019-07-28. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- ↑ Akmam W (2002). "Women's Education and Fertility Rates in Developing Countries, With Special Reference to Bangladesh". Eubios Journal of Asian and International Bioethics. 12: 138–143. Archived from the original on 2022-04-12. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ↑ Ahmad A (2013). "Global Population and Demographic Trends". New Age Globalization. pp. 33–60. doi:10.1057/9781137319494_3. ISBN 978-1-349-45115-9.

- ↑ Zhu WX (June 2003). "The one child family policy". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 88 (6): 463–4. doi:10.1136/adc.88.6.463. PMC 1763112. PMID 12765905.

- ↑ Hesketh T, Zhou X, Wang Y (2015). "The End of the One-Child Policy: Lasting Implications for China". JAMA. 314 (24): 2619–20. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.16279. PMID 26545258.

- ↑ Gilbert G (2005). World Population: A Reference Handbook (Contemporary world issues). ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851099276. Page 25 Archived 2021-05-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "China to end one-child policy and allow two". BBC News. 29 October 2015. Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ↑ Ramu GN (2006), Brothers and sisters in India: a study of urban adult siblings, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-9077-5, archived from the original on 2016-05-03, retrieved 2022-06-12

- ↑ "CIA, The World Fact Book, India, 7/24/2017". Archived from the original on 2021-03-18. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ↑ Murthy N (2010). Better India, A Better World. Penguin Books India. p. 98. ISBN 9780143068570. Archived from the original on 2021-04-27. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ↑ Lim LL. "Female Labour-Force Participation" (PDF). United Nations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-21. Retrieved 2022-06-12., part of Completing the Fertility Transition. United Nations Publications. 2009. ISBN 9789211513707.

- ↑ Ahn N, Mira P (2002). "A Note on the Changing Relationship between Fertility and Female Employment Rates in Developed Countries" (PDF). Journal of Population Economics. 15 (4): 667–682. doi:10.1007/s001480100078. JSTOR 20007839. S2CID 17755082. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-08-02. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ↑ Anderson SE, Dallal GE, Must A (April 2003). "Relative weight and race influence average age at menarche: results from two nationally representative surveys of US girls studied 25 years apart". Pediatrics. 111 (4 Pt 1): 844–50. doi:10.1542/peds.111.4.844. PMID 12671122.

- ↑ Al-Sahab B, Ardern CI, Hamadeh MJ, Tamim H (November 2010). "Age at menarche in Canada: results from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children & Youth". BMC Public Health. 10: 736. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-736. PMC 3001737. PMID 21110899.

- ↑ Hamilton-Fairley, Diana (2004). "Obstetrics and Gynaecology: Lecture Notes" (PDF) (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishing. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-10-09. Retrieved 2012-08-26.

- 1 2 Kidd SA, Eskenazi B, Wyrobek AJ (February 2001). "Effects of male age on semen quality and fertility: a review of the literature". Fertility and Sterility. 75 (2): 237–48. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(00)01679-4. PMID 11172821.

- ↑ Das KC, Gautam V, Das K, Tripathy PK (2011). "Influence of age gap between couples on contraception and fertility" (PDF). Journal of Family Welfare. 57 (2). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-08-19. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ↑ "Causes of infertility". National Health Service. 2017-10-23. Archived from the original on 2016-02-29. Retrieved 2018-11-17.

- ↑ Cooper TG, Noonan E, von Eckardstein S, Auger J, Baker HW, Behre HM, et al. (2009). "World Health Organization reference values for human semen characteristics". Human Reproduction Update. 16 (3): 231–45. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmp048. PMID 19934213.

- ↑ Rijken AJ, Liefbroer AC (2008). "The Influence of Partner Relationship Quality on Fertility [L'influence de la qualité de la relation avec le partenaire sur la fécondité]". European Journal of Population / Revue Européenne de Démographie. 25 (1): 27–44. doi:10.1007/s10680-008-9156-8. ISSN 0168-6577.

- ↑ Currie J, Schwandt H (October 2014). "Short- and long-term effects of unemployment on fertility". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (41): 14734–9. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11114734C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1408975111. PMC 4205620. PMID 25267622.

- ↑ Mathews TJ (August 2009). "Delayed Childbearing: More Women Are Having Their First Child Later in Life" (PDF). NCHS Data Brief. No 21: 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-11-25. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- 1 2 Freja T (July 2008). "Fertility in Europe: Diverse, delayed and below replacement" (PDF). Demographic Research. 19, Article 3: 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-03-19. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ↑ Graff H (Mar 1979). "Literacy, Education, and Fertility, Past and Present: A Critical Review". Population and Development Review. 5 (1): 105–140. doi:10.2307/1972320. JSTOR 1972320.

- ↑ Gauthier A, Hatzius J (1997). "Family benefits and fertility: An econometric analysis". Population Studies. 51 (3): 295–306. doi:10.1080/0032472031000150066. JSTOR 2952473.

- 1 2 Beaujouan E (2011). "Second-Union Fertility in France: Partners' Age and Other Factors". Population English Edition. 66 (2): 239. doi:10.3917/pope.1102.0239. S2CID 145016461. Archived from the original on 2021-05-11. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ↑ Krzyżanowska M, Mascie-Taylor CG, Thalabard JC (2015). "Is human mating for height associated with fertility? Results from a British National Cohort Study". American Journal of Human Biology. 27 (4): 553–63. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22684. PMID 25645540. S2CID 38106234.

- 1 2 "Healthy Mothers and Healthy Newborns: The Vital Link". www.prb.org. Archived from the original on 2017-03-30. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ↑ Kearney MS, Levine PB (2012-01-01). "Why is the teen birth rate in the United States so high and why does it matter?". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 26 (2): 141–66. doi:10.1257/jep.26.2.141. JSTOR 41495308. PMID 22792555.

- ↑ Kahr MK (January 2016). "American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology". Birth Rates Among Hispanics and Non-Hispanics and Their Representation in Clinical Trials in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 214: S296–S297. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.10.595.

Further reading

- Balbo N, Billari FC, Mills M (February 2013). "Fertility in Advanced Societies: A Review of Research: La fécondité dans les sociétés avancées: un examen des recherches". European Journal of Population. 29 (1): 1–38. doi:10.1007/s10680-012-9277-y. PMC 3576563. PMID 23440941.