Flexor retinaculum of the hand

| Flexor retinaculum of the hand | |

|---|---|

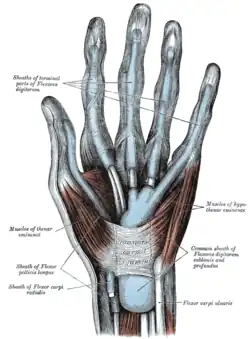

The mucous sheaths of the tendons on the front of the wrist and digits. (Transverse carpal ligament labeled at center.) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | retinaculum musculorum flexorum manus (obsolete: ligamentum transversum carpi)[1] |

| TA98 | A04.6.03.013 |

| TA2 | 2550 |

| FMA | 39988 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The flexor retinaculum (transverse carpal ligament, or anterior annular ligament) is a fibrous band on the palmar side of the hand near the wrist. It arches over the carpal bones of the hands, covering them and forming the carpal tunnel.

Structure

The flexor retinaculum is a strong, fibrous band that covers the carpal bones on the palmar side of the hand near the wrist. It attaches to the bones near the radius and ulna. On the ulnar side, the flexor retinaculum attaches to the pisiform bone and the hook of the hamate bone. On the radial side, it attaches to the tubercle of the scaphoid bone, and to the medial part of the palmar surface and the ridge of the trapezium bone.

The flexor retinaculum is continuous with the palmar carpal ligament, and deeper with the palmar aponeurosis. The ulnar artery and ulnar nerve, and the cutaneous branches of the median and ulnar nerves, pass on top of the flexor retinaculum. On the radial side of the retinaculum is the tendon of the flexor carpi radialis, which lies in the groove on the greater multangular between the attachments of the ligament to the bone.

The tendons of the palmaris longus and flexor carpi ulnaris are partly attached to the surface of the retinaculum; below, the short muscles of the thumb and little finger originate from the flexor retinaculum.

Function

The flexor retinaculum is the roof of the carpal tunnel, through which the median nerve and tendons of muscles which flex the hand pass.

Clinical significance

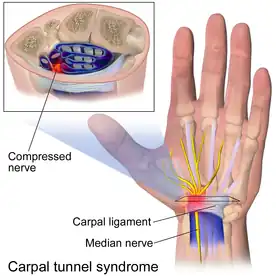

In carpal tunnel syndrome, one of the tendons or tissues in the carpal tunnel is inflamed, swollen, or fibrotic and puts pressure on the other structures in the tunnel, including the median nerve. Carpal tunnel syndrome is the most commonly reported nerve entrapment syndrome.[2] Carpal tunnel syndrome is often associated with repetitive motions of the wrist and fingers; jobs like typists, pianists, and meat cutters are at particularly high risk. The tough flexor retinaculum along with the rest of the carpal tunnel cannot expand, putting pressure on the median nerve running through the carpal tunnel with the flexor tendons of the wrist. This results in the symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome.[3]

Symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome include tingling sensations and muscle weakness in the palm and lateral side of the hand and palm. It is possible that the syndrome may extend and radiate up the nerve causing pain to the arm and shoulder.[4]

Carpal tunnel syndrome may be treated surgically; although this is usually done after all non-surgical methods of treatment have been exhausted. Non-surgical treatment methods include anti-inflammatory drugs. Additionally, the wrist may also be immobilized in order to prevent further use and inflammation. When surgery is needed, the flexor retinaculum is either completely severed or lengthened.[5] When surgery is done to divide the flexor retinaculum, by far the more common procedure, scar tissue will eventually fill the gap left by surgery. The intent is that this will lengthen the flexor retinaculum enough to accommodate inflamed or damaged tendons and reduce the effects of compression on the median nerve. In a 2004 double blind-study, researchers concluded that there was no perceivable benefit gained from lengthening the flexor retinaculum during surgery and so division of the ligament remains the preferred method of surgery.[6]

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 456 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 456 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ↑ Kachlika, David; Bozdechovac, Ivana; Cechd, Pavel; Musile, Vladimir; Bacaa, Vaclav (2009). "Mistakes in the usage of anatomical terminology in clinical practice". Biomedical Papers of the Medical Faculty of the University Palacky, Olomouc, Czechoslovakia. 153 (2): 157–61. doi:10.5507/bp.2009.027. PMID 19771143.

- ↑ Silverstein, Barbara A.; Fine, Lawrence J.; Armstrong, Thomas J. (1987). "Occupational factors and carpal tunnel syndrome". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 11 (3): 343–358. doi:10.1002/ajim.4700110310. PMID 3578290.

- ↑ Saladin, Kenneth S. Anatomy & Physiology The Unity of Form and Function. 6th. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012.

- ↑ Saladin, Kenneth S. Anatomy & Physiology The Unity of Form and Function. 7th. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2015.

- ↑ Saladin, Kenneth S. Anatomy & Physiology The Unity of Form and Function. 7th. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2015.

- ↑ Dias, J.J.; Bhowal, B.; Wildin, C.J.; Thompson, J.R. (10 January 2017). "Carpal Tunnel Decompression. Is Lengthening of the Flexor Retinaculum Better than Simple Division?". Journal of Hand Surgery. 29 (3): 269–274. doi:10.1016/j.jhsb.2004.01.011. PMID 15142699. S2CID 25503344.

External links

- Anatomy figure: 08:04-08 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Hand kinesiology at the University of Kansas Medical Center

- lesson5flexretinac&palmapon at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University)