Food and diet in ancient medicine

Modern understanding of disease is very different from the way it was understood in ancient Greece and Rome. The way modern physicians approach healing of the sick differs greatly from the methods used by early general healers or elite physicians like Hippocrates or Galen. In modern medicine, the understanding of disease stems from the "germ theory of disease", a concept that emerged in the second half of the 19th century, such that a disease is the result of an invasion of a micro-organism into a living host. Therefore, when a person becomes ill, modern treatments "target" the specific pathogen or bacterium in order to "beat" or "kill" the disease.

In Ancient Greece and Rome, disease was literally understood as dis-ease, or physical imbalance. Medical intervention, therefore, was purposed with goal of restoration of harmony rather than waging a war against disease.[1] Surgery was regarded by Greek and Roman physicians as extreme and damaging while prevention was seen as the crucial first step to healing almost all ailments. In both prevention and treatment of disease in classical medicine, food and diet was central. The eating of correctly-balanced foods made up the majority of preventative treatment as well as to restore harmony to the body after it encountered disease.

Food and diet in Ancient Greece

Humours and causes of disease

Ancient Greek medicine is described as rational, ethical and based upon observation, conscious learning and experience. Superstition and religious dogmatism are often excluded from descriptions of ancient Greek medicine.[2] It is important, however, to note that this rational approach to medicine did not always exist in the ancient Greek medical world, nor was it the only popular method of healing. Along with rational Greek medicine, disease was also thought of as being of supernatural origin, resulting from the gods inflicting punishment or from demonic possession. Healing was also considered to be a gift from the gods.[3] Exorcists and religious healers were among the ‘doctors’ that patients sought out when they became ill. Sacrifices, exorcisms, spells and prayers were then carried out in order to reconcile with the gods and restore health to the patient.

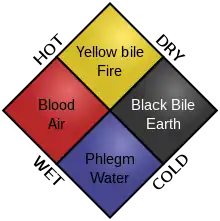

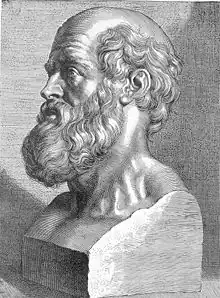

It was not until the time of Hippocrates, between 450 and 350 BC, that rational, observational and the humoral theory of medicine began to become highly influential.[4] According to Hippocrates, diseases are derived from the imbalance of bodily substances. These substances are known as the humors. The humoral theory explains one's behavior and health conditions. The idea of humors in the human body reflected the four terrestrial elements: air, fire, earth, and water. The human body is composed of four essential substances (humors): yellow bile (fire), black bile (earth), blood (air), and phlegm (water). These humors have to be in equilibrium for our body to be in good health. Diseases can be treated by retrieving humoral equilibrium. Galen added to the humoral theory and proposed that humors explained physiological states known as temperaments.[5] These temperaments are sanguine (dominated by the humor blood), choleric (dominated by yellow bile), melancholy (dominated by black bile), and phlegmatic (dominated by phlegm). The ideal proportion to attain harmony is "one quarter as much phlegm as blood, one sixteenth as much choler as blood, and one sixty-fourth as much melancholy as blood."[6] These proportion, however, are difficult to achieve since humors are affected accordingly to what individuals consume in their body.

Foods are classified according to the humoral theory. Food is palatable when hot, wet, dry, cold are in harmony, while food is unpalatable when these elements are imbalanced. Some foods produce good juices and others bad juices and often cooking and preparation of the foods can change or improve the juices of the foods. In addition, foods may be easy to assimilate (easy to pass through the body), easily excreted, nourishing or not nourishing.[1]: 338 In Hippocratic medicine, the qualities in foods are analogous to the four humors in the body: too much of a single one is bad, a proper mixture is ideal.[1]: 347 It was believed that the choice of diet had medical consequences. Therefore, the consumption of correctly-balanced foods and life-style of the patient was crucial to the prevention and treatment of disease in Ancient Greece.

Seasonal food played an important role in the treatment of ancient disease. According to the Hippocratic author of “Airs, Waters and Places” (there remains debate as to whether Hippocrates himself wrote the Hippocratic Corpus), it is important that a physician learn astronomy because, “the changes of the seasons produce changes in diseases,”.[7] In the same Hippocratic text, the author goes on to explain that villages facing east and that are exposed to winds from the north-east, south-east and west tended to be healthy and, “the climate in such a district may be compared with the spring in that there are no extremes of heat and cold. As a consequence, diseases in such a district are few and not severe”.[7]: 151 As an example of the importance of seasonal food on maintaining balance of the humours and preventing disease is given by Hippocrates in “On Regimen” when the authors state that, “in winter, to secure a dry and hot body it is better to eat wheaten bread, roast meat, and few vegetables; whereas in summer it is appropriate to eat barley cake, barley meat and softer foods,” (qtd. in Wilkins et al., p. 346).

Food and diet in the Hippocratic aphorisms

Food and diet feature prominently in the aphorisms of the Hippocratic Corpus. For example, in one aphorism in the first section, Hippocrates states, “Things which are growing have the greatest natural warmth and, accordingly, need most nourishment. Failing this the body becomes exhausted. Old men have little warmth and they need little food which produces warmth; too much only extinguishes the warmth they have. For this reason, fevers are not so acute in old people for then the body is cold”.[7]: 208 Another aphorism says, “It is better to be full of drink than full of food”.[7]: 209 And finally, an aphorism that generally sums up treatment of disease in Hippocratic times states, “Disease which results from over-eating is cured by fasting; disease following fasting, by a surfeit. So with other things; cures may be effected by opposites,”.[7]: 210

This concept of treating diseases opposite to the way it manifests in the individual is concept that is carried over into Roman medicine. Hippocratic doctors encouraged the rejection of divine intervention and began to view the body more objectively.[8] This monumental stray from anthropomorphic intervention placed a greater emphasis on physicians to find a physical remedy for those in need. One of the popular remedies observed in the Hippocratic Corpus is the use of red wine.[8] Because many physicians believed that red wine paralleled blood, it could be used to provide health and comfort as a result of its "hot and dry" nature. While it was seen in a positive light, many Hippocratic physicians were also aware of the negative aspects of wine consumption along with the physical consequences of doing so.[8]

Gout in Ancient Greece

Gout was called podagra in ancient Greek medicine and is a common arthritis caused by deposition of monosodium urate crystals within the joints.[9] Gout usually affects the first metatarsophalangeal joint of the big toe and later the other joints of the feet and hands. Hippocrates considered gout to be the result of an accumulation of one of the body humours that distended the joint and caused pain.[10] Hippocrates also believed gout to be a result from sexual excess or too rich a diet as alluded to in three of his aphorisms “Eunuchs do not take the gout nor become bald”, “A woman does not take the gout unless her menses has stopped”, and “A young man does not take the gout until he indulges coitus”.[9]: 84 [10]: 14–15 As with other diseases, physicians in antiquity believed that diet was the best way to manage gout. Hippocrates recommended high doses of white hellebore because he believed that the best and most natural relief for gout was dysentery.[9]: 85 However, purging with white hellebore was probably for the more chronic cases due to the fact that wine and barleywater drinks were very strongly recommended.[10]: 16–17

Legumes in Ancient Greece

The importance of legumes in ancient Greek diet and medical practice is often disregarded. However, legumes improved the quality of the soil and were considered very important to the agriculturalists of the time. Additionally, legumes contain a high amount of albumen, which led them to be a critical dietary supplement in countries where meat was in short supply and difficult to store. Such was the case with Greece. People in the Graeco-Roman world consumed less meat than we do today and therefore, legumes were a necessary source of protein.[11] Of all legumes, the lentil appears most frequently in Greek and Roman literature. Medicinally, Hippocrates recommends lentils as a remedy for ulcers and hemorrhoids.[11]: 376

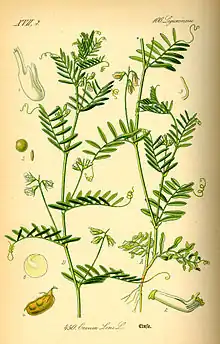

Bitter vetch, or Vicia ervilia, was also an important legume in ancient Greek medicine. The extensive medicinal qualities of the bitter vetch were thought reliable enough to later administer to Roman emperors such as Augustus.[11]: 379 Bitter vetch was thought to heal pimples, prevent sores from spreading and soothe spots or sores when they appear on the breasts. It was also reported to relieve painful urination, flatulence, liver problems, and indigestion when roasted and mixed with honey and Hippocrates cautioned that when eaten boiled or raw, the consumption of bitter vetch may cause more flatulence or pain.[11]: 379

Food and diet in Ancient Rome

Humours, anatomy and the causes of disease

At the heart of Roman medicine and central to the development of Western medicine is Galen of Pergamum (AD 129–c. AD 210).[12] Galen was a prolific writer from whose surviving works comes what Galen believed to be the definitive guide to a healthy diet, based on the theory of the four humours.[13] Galen understood the humoral theory in a dynamic sense rather than static sense such that yellow bile is hot and dry like fire; black bile is dry and cold like earth; phlegm is cold and moist like water; and blood is moist and hot.[14] He also understood the humours to be produced by food through digestion and it is with digestion, and respiration, that Galen applies his knowledge of anatomy.

According to Galen, digestion begins in the mouth because this where food comes into contact with the saliva. The chewed food is then pulled into the stomach where the heat of the stomach cooks the food into chyle. The chyle is then carried to the liver where the nutrients are converted to blood and transported throughout the body.[14]: 420–421 With this understanding of the humours as being dynamic, and his knowledge of anatomy, Galen was able to categorize illnesses as hot, cold, dry or moist and attribute the causes of these illnesses to specific types of foods. For example, in Galen's own “On the Causes of Disease”, as cited by Mark Grant, Galen says when describing hot diseases that, “[one cause of excessive heat] lies in foods that have hot and harsh powers, such as garlic, leeks, onions, and so on. Immoderate use of these foods sometimes sparks a fever”.[13]: 48 Galen believed that a good physician must also be a good cook.[13]: 11 Therefore, in Galen's dietary treatise “On the Powers of Foods”, recipes are often given in addition to descriptions of foods as being salty or sweet, sour or watery, difficult or easy to digest, costive or laxative, cooling or heating, etc. Galen insists that the balance of the four humors can be beneficially or adversely effected by ‘diet’ which in Galenic medicine includes not just food and drink but also physical exercise, baths, massage, and climate.[15]

The Ancient Greece classified cancer as a peculiar illness that is caused by the excessive amount of black bile. This is due to the fact that out of the four humors, blood is indicative of good health. On the contrary, black bile attributes are the opposite. Thus, the black bile humor is often referred to as an element that is most susceptible to illnesses. It is an element that is time consuming as it takes approximately two weeks to be ready to expel. Even though cancer was not well identified during this time it was known as something that was difficult to treat since black bile equilibrium was challenging to obtain.[16]

Food and the treatment of disease in Ancient Rome

As mentioned, certain types of food can affect the balance of the humours in different ways. Diseases can be treated naturally through the choice of food based upon the idea of balance. According to Galen's “On Humours,” as referenced by Wilkins et al., beef, camel, and goat meat, snails, cabbage, and soft cheeses produce black bile; brains, fungi, and hard apples cause phlegm; bitter almonds and garlic reduce phlegm.[1]: 377 Additionally, for the treatment of gout, Galen suggested a range of dressings to be applied to the affected area made of mandrake, caper, and henbane and for the acute phase, creams made of seeds of conium, mushroom, and deer brain were administered.[9]: 86

During the Ancient Rome period (753 BC–476 AD), medicine was not a well known concept. Diseases were believed to be some sort of penalty, in other words, punishment from God for people's wrongdoings. The only people that were able to provide healing were the priests since they have the connection to the divinities. Priests were doctors at the time; often known as priest-doctors. They served as medical providers under the respect of many community members due to their high spiritual standing and morality. It was also believed that these doctors would not have been able to provide healing without the assistance from God.[17]

In Rome, treatments were frequently exercised within families. The healing process is mostly through the use of vegetables and magic formulas. One of the main providers of treatments were the paterfamilias. These 'head of household' men were responsible for providing their wives and children with proper foods when they were sick as well as many other responsibilities.[18] They also incorporated some of Greeks practices including the four humors through the introduction of a Greek medical practitioner, Archagathus of Sparta.[19] Additional to the contributions by Archagathus of Sparta, many Greek doctors and scientists found themselves in Rome as prisoners of war. Aside from captivity, these Greek doctors and scientists also preferred practicing medicine in Rome due to the relatively better financial incentive that existed.[20] Later on in the 3rd century, the Roman expanded their findings and adopted a theological treatment system known as the cult of Aesculapius where thermal baths were used to treat illnesses. The Romans also held the belief that the body and brain are one. They believed that if one has a healthy mind, their body wellness will follow.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Wilkins, John; et al. (1995). Food in Antiquity. University of Exeter Press. p. 345. ISBN 0-85989-418-5.

- ↑ EDELSTEIN, LUDWIG (1937). "Greek Medicine in ITS Relation to Religion and Magic". Bulletin of the Institute of the History of Medicine. 5 (3): 201–246. ISSN 2576-4810. JSTOR 44438180.

- ↑ "Ancient Greek Medicine". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- ↑ Nutton, Vivian (1999). "Healing and the healing act in Classical Greece". European Review. 7 (1): 30. doi:10.1017/S1062798700003719.

- ↑ "Four Humors - And there's the humor of it: Shakespeare and the four humors". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- ↑ "The Four Humors: Eating in the Renaissance". Shakespeare & Beyond. 2015-12-04. Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chadwick, edited with an introduction by G.E.R. Lloyd ; translated [from the Greek] by J.; al.], W.N. Mann ... [et (1983). Hippocratic writings ([New] ed., with additional material, Repr. in Penguin classics. ed.). Harmondsworth: Penguin. p. 149. ISBN 0-14-044451-3.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - 1 2 3 Van der Eijk, Philip, editor. “WINE AND MEDICINE IN ANCIENT GREECE.” Greek Medicine from Hippocrates to Galen: Selected Papers, by Jacques Jouanna and Neil Allies, Brill, LEIDEN; BOSTON, 2012, pp. 173–194. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w76vxr.15. Accessed 18 Dec. 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Gritzalis, Konstantinos C. (2011). "Gout in the Writings of Eminent Ancient Greek and Byzantine Physicians". Acta Med-hist Adriat. 9 (1): 83–8. PMID 22047483.

- 1 2 3 Porter, Roy; Rousseau, G.S. (2000). Gout: The Patrician Malady. Yale University Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-300-08274-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Flint-Hamilton, Kimberly B. (1999). "Legumes in Ancient Greece and Rome: Food, Medicine, or Poison?". Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. 68 (3): 374. doi:10.2307/148493. JSTOR 148493.

- ↑ Conrad, Lawrence I. (1998). The Western medical tradition, 800 BC to AD 1800 (Reprinted. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 58–70. ISBN 0-521-47564-3.

- 1 2 3 Grant, Mark (2000). Galen on Food and Diet. London: Routledge. p. 10. ISBN 0-415-23232-5.

- 1 2 Prioreschi, Plinio (1998). A History of Medicine: Roman medicine. Edwin Mellen Press. p. 360. ISBN 978-1-888456-03-5.

- ↑ Singer, P.N (1997). Galen selected works. England: Oxford University Press. p. X. ISBN 978-0-19-158627-9.

- ↑ Hays, Jeffrey. "HEALTH AND DISEASE IN ANCIENT ROME | Facts and Details". factsanddetails.com. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- ↑ Santacroce, Luigi; Bottalico, Lucrezia; Charitos, Ioannis Alexandros (2017-12-12). "Greek Medicine Practice at Ancient Rome: The Physician Molecularist Asclepiades". Medicines. 4 (4): 92. doi:10.3390/medicines4040092. ISSN 2305-6320. PMC 5750616. PMID 29231878.

- ↑ “Household Medicine In Ancient Rome.” The British Medical Journal, vol. 1, no. 2140, 1902, pp. 39–40. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20270775. Accessed 18 Dec. 2020.

- ↑ "Ancient Roman medicine: Influences, practice, and learning". www.medicalnewstoday.com. 2018-11-09. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- ↑ Van der Eijk, Philip, editor. “EGYPTIAN MEDICINE AND GREEK MEDICINE.” Greek Medicine from Hippocrates to Galen: Selected Papers, by Jacques Jouanna and Neil Allies, Brill, LEIDEN; BOSTON, 2012, pp. 3–20. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w76vxr.6. Accessed 18 Dec. 2020.