Forensic facial reconstruction

| Part of a series on |

| Forensic science |

|---|

|

|

Forensic facial reconstruction (or forensic facial approximation) is the process of recreating the face of an individual (whose identity is often not known) from their skeletal remains through an amalgamation of artistry, anthropology, osteology, and anatomy. It is easily the most subjective—as well as one of the most controversial—techniques in the field of forensic anthropology. Despite this controversy, facial reconstruction has proved successful frequently enough that research and methodological developments continue to be advanced.

In addition to remains involved in criminal investigations, facial reconstructions are created for remains believed to be of historical value and for remains of prehistoric hominids and humans.

Types of identification

There are two forms pertaining to identification in forensic anthropology: circumstantial and positive.[1]

- Circumstantial identification is established when an individual fits the biological profile of a set of skeletal or largely skeletal remains. This type of identification does not prove or verify identity because any number of individuals may fit the same biological description.

- Positive identification, one of the foremost goals of forensic science, is established when a unique set of biological characteristics of an individual are matched with a set of skeletal remains. This type of identification requires the skeletal remains to correspond with medical or dental records, unique ante mortem wounds or pathologies, DNA analysis, and still other means.[2]

Facial reconstruction presents investigators and family members involved in criminal cases concerning unidentified remains with a unique alternative when all other identification techniques have failed.[3] Facial approximations often provide the stimuli that eventually lead to the positive identification of remains.

Legal admissibility

In the U.S., the Daubert Standard is a legal precedent set in 1993 by the Supreme Court regarding the admissibility of expert witness testimony during legal proceedings, set in place to ensure that expert testimony is based on sufficient facts or data, derived from proper application of reliable principles and methods.[4] When multiple forensic artists produce approximations for the same set of skeletal remains, no two reconstructions are ever the same and the data from which approximations are created are largely incomplete.[5] Because of this, forensic facial reconstruction does not uphold the Daubert Standard, is not considered a legally recognized technique for positive identification, and is not admissible as expert testimony. Currently, reconstructions are only produced to aid the process of positive identification in conjunction with verified methods.

Types of reconstructions

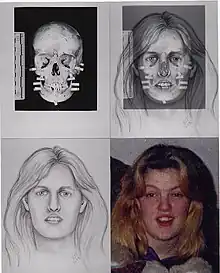

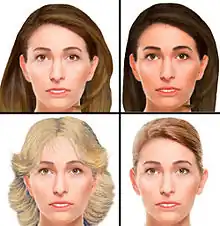

Two-dimensional reconstructions

Two-dimensional facial reconstructions are based on ante mortem photographs, and the skull. Occasionally skull radiographs are used but this is not ideal since many cranial structures are not visible or at the correct scale. This method usually requires the collaboration of an artist and a forensic anthropologist. A commonly used method of 2D facial reconstruction was pioneered by Karen T. Taylor of Austin, Texas during the 1980s.[7] Taylor's method involves adhering tissue depth markers on an unidentified skull at various anthropological landmarks, then photographing the skull. Life-size or one-to-one frontal and lateral photographic prints are then used as a foundation for facial drawings done on transparent vellum. Recently developed, the F.A.C.E. and C.A.R.E.S. computer software programs quickly produce two-dimensional facial approximations that can be edited and manipulated with relative ease. These programs may help speed the reconstruction process and allow subtle variations to be applied to the drawing, though they may produce more generic images than hand-drawn artwork.[3]

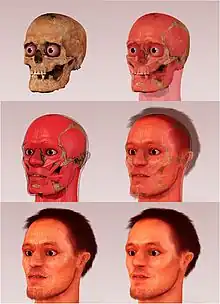

Three-dimensional reconstructions

Three-dimensional facial reconstructions are either: 1) sculptures (made from casts of cranial remains) created with modeling clay and other materials or 2) high-resolution, three-dimensional computer images. Like two-dimensional reconstructions, three-dimensional reconstructions usually require both an artist and a forensic anthropologist. Computer programs create three-dimensional reconstructions by manipulating scanned photographs of the unidentified cranial remains, stock photographs of facial features, and other available reconstructions. These computer approximations are usually most effective in victim identification because they do not appear too artificial.[3] This method has been adopted by the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, which uses this method often to show approximations of an unidentified decedent to release to the public in hopes to identify the subject.[8]

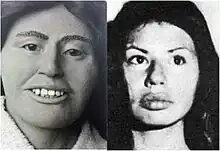

Superimposition

Superimposition is a technique that is sometimes included among the methods of forensic facial reconstruction. It is not always included as a technique because investigators must already have some kind of knowledge about the identity of the skeletal remains with which they are dealing (as opposed to 2D and 3D reconstructions, when the identity of the skeletal remains are generally completely unknown). Forensic superimpositions are created by superimposing a photograph of an individual suspected of belonging to the unidentified skeletal remains over an X-ray of the unidentified skull. If the skull and the photograph are of the same individual, then the anatomical features of the face should align accurately.[9]

History

Hermann Welcker in 1883 and Wilhelm His, Sr. in 1895, were the first to reproduce three-dimensional facial approximations from cranial remains.[10] Most sources, however, acknowledge His as the forerunner in advancing the technique. His also produced the first data on average facial tissue thickness followed by Kollmann and Buchly who later collected additional data and compiled tables that are still referenced in most laboratories working on facial reproductions today.[11]

Facial reconstruction originated in two of the four major subfields of anthropology. In biological anthropology, they were used to approximate the appearance of early hominid forms, while in archaeology they were used to validate the remains of historic figures. In 1964, Mikhail Gerasimov was probably the first to attempt paleo-anthropological facial reconstruction to estimate the appearance of ancient peoples[12]

Although students of Gerasimov later used his techniques to aid in criminal investigations, it was Wilton M. Krogman who popularized facial reconstruction's application to the forensic field. Krogman presented his method for facial reconstruction in his 1962 book, detailing his method for approximation.[12] Others who helped popularize three-dimensional facial reconstruction include Cherry (1977), Angel (1977), Gatliff (1984), Snow (1979), and Iscan (1986).[3]

In 2004 it was for Dr. Andrew Nelson of the University of Western Ontario, Department of Anthropology that noted Canadian artist Christian Corbet created the first forensic facial reconstruction of an approximately 2,200-year-old mummy based on CT and laser scans. This reconstruction is known as the Sulman Mummy project.

Technique for creating a three-dimensional clay reconstruction

Because a standard method for creating three-dimensional forensic facial reconstructions has not been widely agreed upon, multiple methods and techniques are used. The process detailed below reflects the method presented by Taylor and Angel from their chapter in Craniofacial Identification in Forensic Medicine, pgs 177-185.[13] This method assumes that the sex, age, and race of the remains to undergo facial reconstruction have already been determined through traditional forensic anthropological techniques.

The skull is the basis of facial reconstruction; however, other physical remains that are sometimes available often prove to be valuable. Occasionally, remnants of soft tissue are found on a set of remains. Through close inspection, the forensic artist can easily approximate the thickness of the soft tissue over the remaining areas of the skull based on the presence of these tissues. This eliminates one of the most difficult aspects of reconstruction, the estimation of tissue thickness. Additionally, any other bodily or physical evidence found in association with remains (e.g. jewelry, hair, glasses, etc.) are vital to the final stages of reconstruction because they directly reflect the appearance of the individual in question.

Most commonly, however, only the bony skull and minimal or no other soft tissues are present on the remains presented to forensic artists. In this case, a thorough examination of the skull is completed. This examination focuses on, but is not limited to, the identification of any bony pathologies or unusual landmarks, ruggedness of muscle attachments, profile of the mandible, symmetry of the nasal bones, dentition, and wear of the occlusal surfaces. All of these features have an effect on the appearance of an individual's face.

Once the examination is complete, the skull is cleaned and any damaged or fragmented areas are repaired with wax. The mandible is then reattached, again with wax, according to the alignment of teeth, or, if no teeth are present, by averaging the vertical dimensions between the mandible and maxilla. Undercuts (like the nasal openings) are filled in with modeling clay and prosthetic eyes are inserted into the orbits centered between the superior and inferior orbital rims. At this point, a plaster cast of the skull is prepared. Extensive detail of the preparation of such a cast is presented in the article from which these methods are presented.

After the cast is set, colored plastics or the colored ends of safety matches are attached at twenty-one specific "landmark" areas that correspond to the reference data. These sites represent the average facial tissue thickness for persons of the same sex, race, and age as that of the remains. From this point on, all features are added using modeling clay.

First, the facial muscles are layered onto the cast in the following order: temporalis, masseter, buccinator and occipito-frontals, and finally the soft tissues of the neck. Next, the nose and lips are reconstructed before any of the other muscles are formed. The lips are approximately as wide as the interpupillary distance. However, this distance varies significantly with age, sex, race, and occlusion. The nose is one of the most difficult facial features to reconstruct because the underlying bone is limited and the possibility of variation is expansive. The nasal profile is constructed by first measuring the width of the nasal aperture and the nasal spine. Using a calculation of three times the length of the spine plus the depth of tissue marker number five will yield the approximate nose length. Next, the pitch of the nose is determined by examining the direction of the nasal spine - down, flat, or up. A block of clay that is the proper length is then placed on the nasal spine and the remaining nasal tissue is filled in using tissue markers two and three as a guide for the bridge of the nose. The alae are created by first marking a point five millimeters below the bottom of the nasal aperture. After the main part of the nose is constructed, the alae are created as small egg-shaped balls of clay, that are five millimeters in diameter at the widest point, these are positioned on the sides of the nose corresponding with the mark made previously. The alae are then blended to the nose and the overall structure of the nose is rounded out and shaped appropriately.

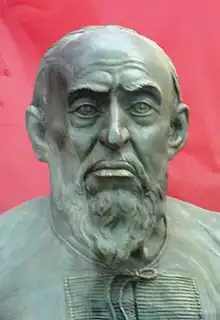

The muscles of facial expression and the soft tissue around the eyes are added next. Additional measurements are made according to race (especially for those with eye folds characteristic of Asian descent) during this stage. Next, tissues are built up to within one millimeter of the tissue thickness markers and the ears (noted as being extremely complicated to reproduce) are added. Finally, the face is "fleshed," meaning clay is added until the tissue thickness markers are covered, and any specific characterization is added (for example, hair, wrinkles in the skin, noted racial traits, glasses, etc.). The skull of Mozart was the basis of his facial reconstruction from anthropological data. The bust was unveiled at the "Salon du Son", Paris, in 1991.[14]

Problems with facial reconstruction

There are multiple outstanding problems associated with forensic facial reconstruction.[15]

Insufficient tissue thickness data

The most pressing issue relates to the data used to average facial tissue thickness. The data available to forensic artists are still very limited in ranges of ages, sexes, and body builds. This disparity greatly affects the accuracy of reconstructions. Until this data is expanded, the likelihood of producing the most accurate reconstruction possible is largely limited.[16]

Lack of methodological standardization

A second problem is the lack of a methodological standardization in approximating facial features.[3] A single, official method for reconstructing the face has yet to be recognized. This also presents major setback in facial approximation because facial features like the eyes and nose and individuating characteristics like hairstyle – the features most likely to be recalled by witnesses – lack a standard way of being reconstructed. Recent research on computer-assisted methods, which take advantage of digital image processing, pattern recognition, promises to overcome current limitations in facial reconstruction and linkage.

Subjectivity

Reconstructions only reveal the type of face a person may have exhibited because of artistic subjectivity. The position and general shape of the main facial features are mostly accurate because they are greatly determined by the skull.[17]

Neolithic dog's head forensic reconstruction

An image of the forensic model of a Neolithic dog skull found at Cuween Hill Chambered Cairn, Orkney, Scotland was published by Sci-News.com on April 22, 2019.

Forensic artist Amy Thornton made a model of the dog's head using a 3D print, based on a CT scan made at the Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies of one of the 24 canine skulls found at the site.

According to Dr. Alison Sheridan, Principal Archaeological Research Curator in the Department of Scottish History and Archaeology at National Museums Scotland, "The size of a large collie, and with features reminiscent of that of a European grey wolf, the Cuween dog has much to tell us ... While reconstructions have previously been made of people from the Neolithic era, we do not know of any previous attempt to forensically reconstruct an animal from this time." [18]

In popular culture

In recent years, the presence of forensic facial reconstructions in the entertainment industry and the media has increased. The way the fictional criminal investigators and forensic anthropologists utilize forensics and facial reconstructions are, however, often misrepresented[19] (an influence known as the "CSI effect"). For example, the fictional forensic investigators will often call for the creation of a facial reconstruction as soon as a set of skeletal remains is discovered. In many instances, facial reconstructions have been used as a last resort to stimulate the possibility of identifying an individual.[20]

Facial reconstruction has been featured as part of an array of forensic science methods in fictional TV shows like CSI: Crime Scene Investigation and NCIS and their respective spinoffs in the CSI and NCIS franchises.

In Bones, a long-running TV series centered around forensic analysis of decomposed and skeletal human remains, facial reconstruction is featured in the majority of episodes, used much like a police artist sketch in police procedurals. Regular cast character Angela Montenegro, the Bones team's facial reconstruction specialist, employs 3D software and holographic projection to "give victims back their faces" (as noted in the episode, "A Boy in a Bush").

In the MacGyver episode "The Secret of Parker House", MacGyver reconstructs the skull of Penny's aunt Betty while investigating her house.

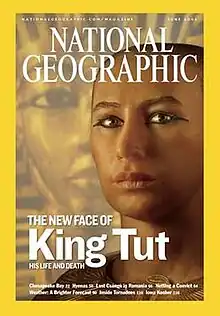

The facial reconstruction of Egypt's Tutankhamun, popularly known as King Tut, made the June 2005 cover of National Geographic.

A variety of facial reconstruction kit toys are available, with "crime scene" versions, also, reconstructions of famous historical figures, like Tutankhamen and the dinosaur Tyrannosaurus rex.

Recently, facial reconstruction has been part of the process used by researchers attempting to identify human remains of two Canadian Army soldiers lost in World War I. One soldier was identified through DNA analysis in 2007, but due to DNA deterioration, identifying the second using the same techniques failed. In 2011, the second of the soldiers' remains discovered at Avion, France were identified through a combination of 3-D printing software, reconstructive sculpture and use of isotopic analysis of bone.[21][22]

References

- ↑ Burns. Forensic Anthropology Training Manual.

- ↑ Reichs and Craig. Facial Approximation: Procedures and Pitfalls.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Reichs and Craig

- ↑ Steadman

- ↑ Helmer et al. Assessment of the Reliability of Facial Reconstruction.

- ↑ Riggs, Robert (11 September 2011). "Robert Riggs Reports Forensic Artist Reconstructs Victims Faces May 2004". Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ↑ Dowling, Paul. "Saving Face." Forensic Files. Prod. Paul Bourdett and Vince Sherry. Dir. Michael Jordan. 28 Nov. 2007. Television.

- ↑ Rodewald, Adam (5 August 2013). "Unidentified murder victim a 'total nightmare' case for detectives". Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ Lundy. Physical Anthropology In Forensic Medicine

- ↑ Forensic Facial Reconstruction: The Final Frontier

- ↑ Rhine. Facial Reproductions In Court.

- 1 2 Iscan. Craniofacial Image Analysis and Reconstruction.

- ↑ Taylor and Angel. Facial Reconstruction and Approximation.

- ↑ Puech PF (1991). "Forensic scientists uncovering Mozart". J R Soc Med. 84 (6): 387. doi:10.1177/014107689108400646. PMC 1293314. PMID 2061918.

- ↑ Lebedinskaya et al. Principles of Facial Reconstruction.

- ↑ Rathbun. Personal Identification: Facial Reproductions.

- ↑ Helmer et al.

- ↑ Scientists Reconstruct Face of Neolithic Dog | Archaeology | Sci-News.com

- ↑ Croom, Nicole (2014-04-17). "The CSI Effect: Science 'As Seen on TV'". synapse.ucsf.edu. Retrieved 2022-02-02.

- ↑ Studies in Crime: An Introduction to Forensic Archaeology ISBN 0-415-16612-8 p. 129

- ↑ Baird, Moira (June 4, 2011). "Where science meets art". The Telegram. Transcontinental Media. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ↑ Quiring, Tami (March 22, 2011). "3D Printing Technology Helped Identify Canadian WW1 Soldier". Village Gamer. Aldergrove, British Columbia. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

Further reading

- Burns, Karen Ramey. Forensic Anthropology Training Manual. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1999

- Gerasimov, Michail M. The Face Finder. New York CRC Press, 1971

- Helmer, Richard et al. Assessment of the Reliability of Facial Reconstruction. Forensic Analysis of the Skull: Craniofacial Analysis, Reconstruction, and Identification. Ed. Mehmet Iscan and Richard Helmer. New York: Wiley-Liss, Inc. 1993. pp. 229-243

- Innes, Brian. Bodies of Evidence. Amber Books Ltd, 2000.

- Iscan, Mehmet Yasar. Craniofacial Image Analysis and Reconstruction. Forensic Analysis of the Skull: Craniofacial Analysis, Reconstruction, and Identification. Ed. Mehmet Iscan and Richard Helmer. New York: Wiley-Liss, Inc. 1993. pp. 1-7

- Lebedinskaya, G.V., T.S. Balueva, and E.V. Veselovskaya. Principles of Facial Reconstruction. Forensic Analysis of the Skull: Craniofacial Analysis, Reconstruction, and Identification. Ed. Mehmet Iscan and Richard Helmer. New York: Wiley-Liss, Inc. 1993. pp. 183-198

- Lundy, John K. Physical Anthropology In Forensic Medicine. Anthropology Today, Vol. 2, No. 5. October 1986. pp. 14-17

- Rathbun, Ted. Personal Identification: Facial Reproductions. Human Identification. Case Studies in Forensic Anthropology. Ed. Ted A. Rathbun and Jane E. Buikstra. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, LTD, 1998. pp. 347-355

- Reichs, Kathleen and Emily Craig. Facial Approximation: Procedures and Pitfalls. Forensic Osteology: Advances in the Identification of Human Remains 2nd Edition. Ed. Kathleen J. Reichs. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, Ltd, 1998. pp. 491-511

- Rhine, Stanley. Facial Reproductions In Court. Human Identification. Case Studies in Forensic Anthropology. Ed. Ted A. Rathbun and Jane E. Buikstra. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, LTD, 1998. pp. 357-361

- Steadman, Dawnie Wolfe. Hard Evidence: Case Studies in Forensic Anthropology. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2003

- Taylor, Karen T. Forensic Art and Illustration. CRC Press, 2000

- Taylor, R. and Angel, C. Facial Reconstruction and Approximation. Craniofacial Identification in Forensic Medicine. Britain: Arnold. 1998. pp. 177-185.

- Wilkinson, Dr Caroline. Forensic Facial Reconstruction. Cambridge University Press, 2004

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Forensic facial reconstruction. |

- Forensic facial reconstruction with free software

- Frank Bender, forensic facial reconstruction artist

- RN-DS Partnership (Richard Neave & Denise Smith)

- Department of Forensic Anthropology, Dundee University, Scotland

- Forensic sculpting step by step in photographs

- Facial reconstruction of the mummy Meresamun in one day

- Karen T. Taylor's Forensic Art Website

- Wesley Neville's Forensic Art Website

- F.B.I. Skeletal Remains Identification by Facial Reconstruction

- Computerised 3D Facial Reconstruction

- Louisiana State University FACES Lab, Baton Rouge LA

- Deutsches Ärzteblatt, 2007; 104(17): A-1160: Forensic Facial Reconstruction – Identification Based on Skeletal Findings, available online: English, German

- Forensic Facial Reconstruction: The Final Frontier

- Rebuilding Faces: Article about Mikhail Gerasimov in Soviet Journal Sputnik, January, 1968