Health effects of chocolate

The health effects of chocolate are the possible positive and negative effects on health. Although considerable research has been conducted to evaluate the potential health benefits of consuming chocolate, there are insufficient clinical research studies to confirm any effect, and no medical or regulatory authority has approved any health claim.

History

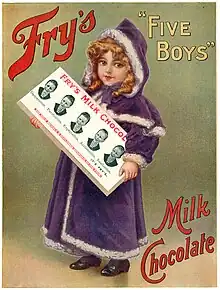

Theobroma cacao, the cacao tree, produces seeds containing flavanols. The seeds have been used to make beverages for some 2000 years in Aztec, Olmec, and Maya civilizations in Central and South America.[1] The drinks were ascribed a wide variety of curative and stimulant properties, unsupported by experimental evidence. In the 19th century, chocolate as a solid was invented, and milk and sugar were added to create milk chocolate, high in fat and sugar. Doubtful research, sometimes funded by the chocolate industry, has at times made suggestions of possible health benefits for these products.[2]

Research

Acne

Overall evidence is insufficient to determine the relationship between chocolate consumption and acne.[3][4] Various studies point not to chocolate, but to the high glycemic nature of certain foods, like sugar, corn syrup, and other simple carbohydrates, as potential causes of acne,[3][4][5][6] along with other possible dietary factors.[3][7]

Addiction

Food, including chocolate, is not typically viewed as addictive.[8] Some people, however, may want or crave chocolate,[8] leading to a self-described term, chocoholic.[8][9]

Mood

By some popular myths, chocolate is considered to be a mood enhancer, such as by increasing sex drive or stimulating cognition, but there is little scientific evidence that such effects are consistent among all chocolate consumers.[10][11] If mood improvement from eating chocolate occurs, there is not enough research to indicate whether it results from the favorable flavor or from the stimulant effects of its constituents, such as caffeine, theobromine, or their parent molecule, methylxanthine.[11] A 2019 review reported that chocolate consumption does not improve depressive mood.[12]

Heart and blood vessels

Reviews support a short-term effect of lowering blood pressure by consuming cocoa products, but there is no evidence of long-term cardiovascular health benefit.[13][14] While daily consumption of cocoa flavanols (minimum dose of 200 mg) appears to benefit platelet and vascular function,[15] there is no good evidence to support an effect on heart attacks or strokes.[15][16]

Lead content

Although research suggests that even low levels of lead in the body may be harmful to children,[17][18] it is unlikely that chocolate consumption in small amounts causes lead poisoning. Some studies have shown that lead may bind to cocoa shells and contamination may occur during the manufacturing process.[19] One study showed the mean lead level in milk chocolate candy bars was 0.027 µg lead per gram of candy;[19] another study found that some chocolate purchased at U.S. supermarkets contained up to 0.965 µg per gram, close to the international (voluntary) standard limit for lead in cocoa powder or beans, which is 1 µg of lead per gram.[20] In 2006, the U.S. FDA lowered by one-fifth the amount of lead permissible in candy, but compliance is only voluntary.[21] Studies concluded that "children, who are big consumers of chocolates, may be at risk of exceeding the daily limit of lead; whereas one 10 g cube of dark chocolate may contain as much as 20% of the daily lead oral limit. Moreover chocolate may not be the only source of lead in their nutrition"[22] and "chocolate might be a significant source of Cd and Pb ingestion, particularly for children."[23]

Polyphenol and theobromine content

Chocolate contains polyphenols, especially flavan-3-ols (catechins) and smaller amounts of other flavonoids,[24] which are under study for their potential effects in the body.[25] The following table shows the content of phenolics, flavonoids and theobromine in three different types of chocolate.

| Type of chocolate | Total phenolics (mg/100g) | Flavonoids (mg/100g) | Theobromine (mg/100g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dark chocolate | 579 | 28 | 883 |

| Milk chocolate | 160 | 13 | 125 |

| White chocolate | 126 | 8 | 0 |

Non-human animals

In sufficient amounts, the theobromine found in chocolate is toxic to animals such as cats, dogs, horses, parrots, and small rodents because they are unable to metabolise the chemical effectively.[26] If animals are fed chocolate, the theobromine may remain in the circulation for up to 20 hours, possibly causing epileptic seizures, heart attacks, internal bleeding, and eventually death. Medical treatment performed by a veterinarian involves inducing vomiting within two hours of ingestion and administration of benzodiazepines or barbiturates for seizures, antiarrhythmics for heart arrhythmias, and fluid diuresis.

A typical 20-kilogram (44 lb) dog will normally experience great intestinal distress after eating less than 240 grams (8.5 oz) of dark chocolate, but will not necessarily experience bradycardia or tachycardia unless it eats at least a half a kilogram (1.1 lb) of milk chocolate. Dark chocolate has 2 to 5 times more theobromine and thus is more dangerous to dogs. According to the Merck Veterinary Manual, approximately 1.3 grams of baker's chocolate per kilogram of a dog's body weight (0.02 oz/lb) is sufficient to cause symptoms of toxicity. For example, a typical 25-gram (0.88 oz) baker's chocolate bar would be enough to bring about symptoms in a 20-kilogram (44 lb) dog. In the 20th century, there were reports that mulch made from cacao bean shells is dangerous to dogs and livestock.[27][28]

References

- ↑ Dillinger, Teresa L.; Barriga, Patricia; Escárcega, Sylvia; Jimenez, Martha; Lowe, Diana Salazar; Grivetti, Louis E. (1 August 2000). "Food of the Gods: Cure for Humanity? A Cultural History of the Medicinal and Ritual Use of Chocolate". The Journal of Nutrition. 130 (8): 2057S–2072S. doi:10.1093/jn/130.8.2057S. ISSN 0022-3166.

- ↑ Fleming, Nic (25 March 2018). "The dark truth about chocolate". The Observer. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 Bhate, K; Williams, H. C. (2013). "Epidemiology of acne vulgaris". British Journal of Dermatology. 168 (3): 474–85. doi:10.1111/bjd.12149. PMID 23210645.

- 1 2 Ferdowsian HR, Levin S (March 2010). "Does diet really affect acne?". Skin Therapy Letter. 15 (3): 1–2, 5. PMID 20361171.

- ↑ Melnik, BC; John, SM; Plewig, G (November 2013). "Acne: risk indicator for increased body mass index and insulin resistance". Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 93 (6): 644–9. doi:10.2340/00015555-1677. PMID 23975508.

- ↑ Mahmood SN, Bowe WP (April 2014). "Diet and acne update: carbohydrates emerge as the main culprit". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 13 (4): 428–35. PMID 24719062.

- ↑ Magin P, Pond D, Smith W, Watson A (February 2005). "A systematic review of the evidence for 'myths and misconceptions' in acne management: diet, face-washing and sunlight". Family Practice. 22 (1): 62–70. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmh715. PMID 15644386.

- 1 2 3 Rogers, Peter J; Smit, Hendrik J (2000). "Food Craving and Food 'Addiction'". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 66 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00197-0. PMID 10837838.

- ↑ Skarnulis, Leanna. "The Chocoholic's Survival Guide". webmd.com. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ Parker, G; Parker, I; Brotchie, H (June 2006). "Mood state effects of chocolate". Journal of Affective Disorders. 92 (2–3): 149–59. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.02.007. PMID 16546266.

- 1 2 Scholey, Andrew; Owen, Lauren (2013). "Effects of chocolate on cognitive function and mood: a systematic review". Nutrition Reviews. 71 (10): 665–681. doi:10.1111/nure.12065. ISSN 0029-6643. PMID 24117885.

- ↑ Veronese N, Demurtas J, Celotto S, Caruso MG, Maggi S, Bolzetta F, Firth J, Smith L, Schofield P, Koyanagi A, Yang L, Solmi M, Stubbs B. (2019). "Is chocolate consumption associated with health outcomes? An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses". Clinical Nutrition. 38 (3): 1101–08. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2018.05.019. PMID 29903472.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Milliron, Tara; Kelsberg, Gary; St Anna, Leilani (2010). "Clinical inquiries. Does chocolate have cardiovascular benefits?". The Journal of Family Practice. 59 (6): 351–2. PMID 20544068.

- ↑ Ried, Karin; Stocks, Nigel P; Fakler, Peter (April 2017). "Effect of cocoa on blood pressure". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 81 (9): 1121–6. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008893.pub3. PMC 6478304. PMID 28439881.

- 1 2 Arranz, S; Valderas-Martinez, P; Chiva-Blanch, G; Casas, R; Urpi-Sarda, M; Lamuela-Raventos, RM; Estruch, R (June 2013). "Cardioprotective effects of cocoa: clinical evidence from randomized clinical intervention trials in humans". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 57 (6): 936–47. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201200595. PMID 23650217.

- ↑ Sudano I, Flammer AJ, Roas S, et al. (August 2012). "Cocoa, blood pressure, and vascular function". Curr. Hypertens. Rep. (Review). 14 (4): 279–84. doi:10.1007/s11906-012-0281-8. PMC 5539137. PMID 22684995.

In the last ten years many research studies confirmed that cocoa does indeed exert beneficial effects on vascular and platelet function.

- ↑ Merrill, J.C.; Morton, J.J.P.; Soileau, S.D. (2007). "Metals". In Hayes, A.W. (ed.). Principles and Methods of Toxicology (5th ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-3778-9.

- ↑ Casarett, LJ; Klaassen, CD; Doull, J, eds. (2007). "Toxic effects of metals". Casarett and Doull's Toxicology: The Basic Science of Poisons (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-147051-3.

- 1 2 Rankin, CW; Nriagu, JO; Aggarwal, JK; Arowolo, TA; Adebayo, K; Flegal, AR (October 2005). "Lead contamination in cocoa and cocoa products: isotopic evidence of global contamination". Environmental Health Perspectives. 113 (10): 1344–1348. doi:10.1289/ehp.8009. PMC 1281277. PMID 16203244.

- ↑ Heneman, Karrie; Zidenberg-Cherr, Sheri (2006). "Is lead toxicity still a risk to U.S. children?". California Agriculture. 60 (4): 180–4. doi:10.3733/ca.v060n04p180.

- ↑ Heller, Lorraine (29 November 2006). "FDA issues new guidance on lead in candy". FoodNavigator.com. Retrieved 15 February 2007.

- ↑ Yanus, Rinat Levi; Sela, Hagit; Borojovich, Eitan J.C.; Zakon, Yevgeni; Saphier, Magal; Nikolski, Andrey; Gutflais, Efi; Lorber, Avraham; Karpas, Zeev (2014). "Trace elements in cocoa solids and chocolate: An ICPMS study". Talanta. 119: 1–4. doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2013.10.048. PMID 24401377.

- ↑ Villa, Javier E. L.; Peixoto, Rafaella R. A.; Cadore, Solange (2014). "Cadmium and Lead in Chocolates Commercialized in Brazil". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 62 (34): 8759–63. doi:10.1021/jf5026604. PMID 25123980.

- ↑ Zięba K, Makarewicz-Wujec M, Kozłowska-Wojciechowska (2019). "Cardioprotective Mechanisms of Cocoa". Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 38 (6): 564–575. doi:10.1080/07315724.2018.1557087. PMID 30620683.

- ↑ Miller, Kenneth B.; Hurst, W. Jeffrey; Flannigan, Nancy; Ou, Boxin; Lee, C. Y.; Smith, Nancy; Stuart, David A. (2009). "Survey of Commercially Available Chocolate- and Cocoa-Containing Products in the United States. 2. Comparison of Flavan-3-ol Content with Nonfat Cocoa Solids, Total Polyphenols, and Percent Cacao". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 57 (19): 9169–80. doi:10.1021/jf901821x. PMID 19754118.

- ↑ Smit HJ (2011). Theobromine and the pharmacology of cocoa. Handb Exp Pharmacol. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 200. pp. 201–34. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-13443-2_7. ISBN 978-3-642-13442-5. PMID 20859797.

- ↑ Drolet, R; Arendt, TD; Stowe, CM (1984). "Cacao bean shell poisoning in a dog". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 185 (8): 902. PMID 6501051.

- ↑ Blakemore, F; Shearer, GD (1943). "The poisoning of livestock by cacao products". Veterinary Record. 55 (15): 165.