Horopter

The horopter was originally defined in geometric terms as the locus of points in space that make the same angle at each eye with the fixation point, although more recently in studies of binocular vision it is taken to be the locus of points in space that have the same disparity as fixation. This can be defined theoretically as the points in space that project on corresponding points in the two retinas, that is, on anatomically identical points. The horopter can be measured empirically in which it is defined using some criterion.

The concept of horopter can then be extended as a geometrical locus of points in space where a specific condition is met:

- the binocular horopter is the locus of iso-disparity points in space;

- the oculomotor horopter is the locus of iso-vergence points in space.

As other quantities that describe the functional principles of the visual system, it is possible to provide a theoretical description of the phenomenon. The measurement with psycho-physical experiments usually provide an empirical definition that slightly deviates from the theoretical one. The underlying theory is that this deviation represents an adaptation of the visual system to the regularities that can be encountered in natural environments.[1][2]

History of the term

The horopter as a special set of points of single vision was first mentioned in the eleventh century by Ibn al-Haytham, known to the west as "Alhazen".[3] He built on the binocular vision work of Ptolemy[4] and discovered that objects lying on a horizontal line passing through the fixation point resulted in single images, while objects a reasonable distance from this line resulted in double images. Thus Alhazen noticed the importance of some points in the visual field but did not work out the exact shape of the horopter and used singleness of vision as a criterion.

The term horopter was introduced by Franciscus Aguilonius in the second of his six books in optics in 1613.[5] In 1818, Gerhard Vieth argued from Euclidean geometry that the horopter must be a circle passing through the fixation-point and the nodal point of the two eyes. A few years later Johannes Müller made a similar conclusion for the horizontal plane containing the fixation point, although he did expect the horopter to be a surface in space (i.e., not restricted to the horizontal plane). The theoretical/geometrical horopter in the horizontal plane became known as the Vieth-Müller circle. However, see the next section Theoretical horopter for the claim that this has been the case of a mistaken identity for about 200 years.

In 1838, Charles Wheatstone invented the stereoscope, allowing him to explore the empirical horopter.[6][7] He found that there were many points in space that yielded single vision; this is very different from the theoretical horopter, and subsequent authors have similarly found that the empirical horopter deviates from the form expected on the basis of simple geometry. Recently, plausible explanation has been provided to this deviation, showing that the empirical horopter is adapted to the statistics of retinal disparities normally experienced in natural environments.[1][2] In this way, the visual system is able to optimize its resources to the stimuli that are more likely to be experienced.

Theoretical Binocular Horopter

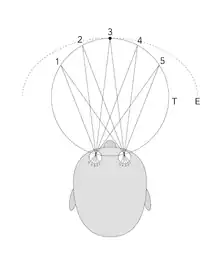

Later Hermann von Helmholtz and Ewald Hering worked out the exact shape of the horopter almost at the same time. Their descriptions identified two components for the horopter for symmetrical fixation closer than infinity. The first is in the plane which contains the fixation point (wherever it is) and the two nodal points of the eye. Historically the geometric locus of horopteric points in this plane was taken to be a circle (the Vieth-Müller circle) going from one nodal point to the other in space and passing through the fixation point, until Howarth (2011) [8] noted that it was only the portion of the circle containing the fixation point that made the same angle at the two eyes. The second component is a line (the Prévost–Burckhardt line) which is perpendicular to this arc in the median plane, cutting it at the point midway between the two eyes (which may, or may not, be the fixation point).[8] This horopter geometry of an arc in the fixation plane and a perpendicular line remains approximately fixed relative to the eye centers as long as the eyes are fixating somewhere on these two lines. When the eyes are fixated anywhere off these two lines, the theoretical horopter takes the form of a twisted cubic passing through the fixation point and asymptoting to the two lines at their extremes.[9] (Under no conditions does the horopter become either a cylinder through the Vieth-Müller circle or a torus centered on the nodal points of the two eyes, as is often popularly assumed.) If the eyes are fixating anywhere at infinity, the Vieth-Müller circle has infinite radius and the horopter becomes the two-dimensional plane through the two straight horopter lines.

In detail, the identification of the theoretical/geometrical horopter with the Vieth-Müller circle is only an approximation. It was pointed out in Gulick and Lawson (1976) [10] that Müller's anatomical approximation that the nodal point and eye rotation center are coincident should be refined. Unfortunately, their attempt to correct this assumption was flawed, as demonstrated in Turski (2016).[11] This analysis shows that, for a given fixation point, one has a slightly different horopter circle for each different choice of the nodal point’s location. Moreover, if one changes the fixation point along a given Vieth-Müller circle such that the vergence value remains constant, one obtains an infinite family of such horopters, to the extent that the nodal point deviates from the eye’s rotation center. These statements follow from the Central Angle Theorem and the fact that three non-collinear points give a unique circle. It can also be shown that, for fixations along a given Vieth-Müller circle, all the corresponding horopter circles intersect at the point of symmetric convergence.[11] This result implies that each member of the infinite family of horopters is also composed of a circle in the fixation plane and a perpendicular straight line passing through the point of symmetric convergence [8](located on the circle) so long as the eyes are in primary or secondary position.

When the eyes are in tertiary position away from the two basic horopter lines, the vertical disparities due to the differential magnification of the distance above or below the Vieth-Müller circle have to be taken into account, as was calculated by Helmholtz. In this case the horopter becomes a single-loop spiral passing through the fixation point and converging toward the vertical horopter at the top and bottom extremities and passing through the nodal point of the two eyes.[9][12] This form was predicted by Helmholtz and subsequently confirmed by Solomons.[13][14] In the general case that includes the fact that the eyes cyclorotate when viewing above or below the primary horopter circle, the theoretical horopter components of the circle and straight line rotate vertically around the axis of the nodal points of the eyes.[9][15]

Empirical Binocular Horopter

As Wheatstone (1838) observed,[7] the empirical horopter, defined by singleness of vision, is much larger than the theoretical horopter. This was studied by Peter Ludvig Panum in 1858. He proposed that any point in one retina might yield singleness of vision with any point within a circular region centred on the corresponding point in the other retina. This has become known as Panum's fusional area,[16] or just Panum's area,[17] although recently that has been taken to mean the area in the horizontal plane, around the Vieth-Müller circle, where any point appears single.

These early empirical investigations used the criterion of singleness of vision, or absence of diplopia to determine the horopter. Today the horopter is usually defined by the criterion of identical visual directions (similar in principle to the apparent motion horopter, according that identical visual directions cause no apparent motion). Other criteria used over the years include the apparent fronto-parallel plane horopter, the equi-distance horopter, the drop-test horopter or the plumb-line horopter. Although these various horopters are measured using different techniques and have different theoretical motivations, the shape of the horopter remains identical regardless of the criterion used for its determination.

Consistently, the shape of the empirical horopter have been found to deviate from the geometrical horopter. For the horizontal horopter this is called the Hering-Hillebrand deviation. The empirical horopter is flatter than predicted from geometry at short fixation distances and becomes convex for farther fixation distances. Moreover the vertical horopter have been consistently found to have a backward tilt of about 2 degrees relative to its predicted orientation (perpendicular to the fixation plane). The theory underlying these deviations is that the binocular visual system is adapted to the irregularities that can be encountered in natural environments.[1][2]

Horopter in computer vision

In computer vision, the horopter is defined as the curve of points in 3D space having identical coordinates projections with respect to two cameras with the same intrinsic parameters. It is given generally by a twisted cubic, i.e., a curve of the form x = x(θ), y = y(θ), z = z(θ) where x(θ), y(θ), z(θ) are three independent third-degree polynomials. In some degenerate configurations, the horopter reduces to a line plus a circle.

References

- 1 2 3 Sprague; et al. (2015). "Stereopsis is adaptive for the natural environment". Science Advances. 1 (4): e1400254. Bibcode:2015SciA....1E0254S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1400254. PMC 4507831. PMID 26207262.

- 1 2 3 Gibaldi; et al. (2017). "The Active Side of Stereopsis: Fixation Strategy and Adaptation to Natural Environments". Scientific Reports. 7: 44800. Bibcode:2017NatSR...744800G. doi:10.1038/srep44800. PMC 5357847. PMID 28317909.

- ↑ Smith, A. Mark (2001). Alhazen's theory of visual perception. Vol. 2 English translation. American Philosophical Society.

- ↑ Smith, A. Mark (1996). Ptolemy's Theory of Visual Perception. American Philosophical Society.

- ↑ Aguilonius, Franciscus. Opticorum libri sex.

- ↑ Glanville AD (1993). "The Psychological Significance of the Horopter". The American Journal of Psychology. 45 (4): 592–627. doi:10.2307/1416191. JSTOR 1416191.

- 1 2 Wheatstone C (1838). "Contributions to the Physiology of Vision. Part the First. On Some Remarkable, and Hitherto Unobserved, Phenomena of Binocular Vision". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 128: 371–94. Bibcode:1838RSPT..128..371W. doi:10.1098/rstl.1838.0019. JSTOR 108203.

- 1 2 3 Howarth PA (2011). "The geometric horopter". Vision Research. 51 (4): 397–9. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2010.12.018. PMID 21256858.

- 1 2 3 Tyler, Christopher W (1991). The horopter and binocular fusion. In Vision and visual dysfunction 9. pp. 19–37.

- ↑ Gulick, W L; Lawson, R B (1976). Human Stereopsis: A psychophysical analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 Turski, Jacek (2016). "On binocular vision: The geometric horopter and Cyclopean eye". Vision Research. 119: 73–81. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2015.11.001. PMID 26548811.

- ↑ Howard, Ian P; Rogers, Brian J (2002). Seeing in depth, volume 2: Depth perception. Ontario, Canada: I. Porteous.

- ↑ Solomons H (1975). "Derivation of the space horopter". The British journal of physiological optics. 30 (2–4): 56–80. PMID 1236460.

- ↑ Solomons H (1975). "Properties of the space horopter". The British journal of physiological optics. 30 (2–4): 81–100. PMID 1236461.

- ↑ Schreiber KM, Tweed DB, Schor CM (2006). "The extended horopter: Quantifying retinal correspondence across changes of 3D eye position". Journal of Vision. 6 (1): 64–74. doi:10.1167/6.1.6. PMID 16489859.

- ↑ Gibaldi, A., Labhishetty, V., Thibos, L. N., & Banks, M. S. (2021). The blur horopter: Retinal conjugate surface in binocular viewing. Journal of Vision, 21(3), 8. https://doi.org/10.1167/jov.21.3.8

- ↑ Ames, A., Jr, & Ogle, K. N. (1932). Size and shape of ocular images: III. Visual sensitivity to differences in the relative size of the ocular images of the two eyes. Archives of Ophthalmology, 7(6), 904-924. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1932.00820130088008