Junctional diversity

Junctional diversity describes the DNA sequence variations introduced by the improper joining of gene segments during the process of V(D)J recombination. This process of V(D)J recombination has vital roles for the vertebrate immune system, as it is able to generate a huge repertoire of different T-cell receptor (TCR) and immunoglobulin molecules required for pathogen antigen recognition by T-cells and B cells, respectively.

Process

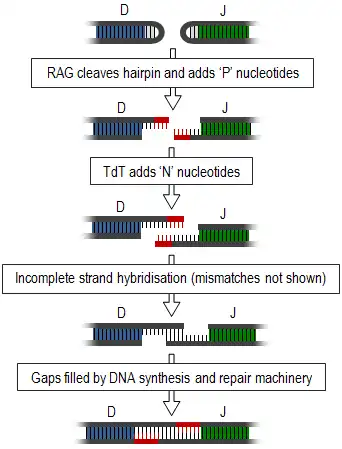

Junctional diversity includes the process of somatic recombination or V(D)J recombination, during which the different variable gene segments (those segments involved in antigen recognition) of TCRs and immunoglobulins are rearranged and unused segments removed. This introduces double-strand breaks between the required segments. These ends form hairpin loops and must be joined together to form a single strand (summarised in diagram, right). This joining is a very inaccurate process that results in the variable addition or subtraction of nucleotides and, thus, generates junctional diversity.[1]

Generation of junctional diversity starts as the proteins, recombination activating gene-1 and -2 (RAG1 and RAG2), along with DNA repair proteins, such as Artemis,[2] are responsible for single-stranded cleavage of the hairpin loops and addition of a series of palindromic, 'P' nucleotides. Subsequent to this, the enzyme, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), adds further random 'N' nucleotides. The newly synthesised strands anneal to one another, but mismatches are common. Exonucleases remove these unpaired nucleotides and the gaps are filled by DNA synthesis and repair machinery.[1][3] Exonucleases may also cause shortening of this junction, however this process is still poorly understood.[4]

Junctional diversity is liable to cause frame-shift mutations and thus production of non-functional proteins. Therefore, there is considerable waste involved in this process.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 Janeway, C.A., Travers, P., Walport, M., Shlomchik, M.J. (2005). Immunology (6th ed.). Garland Science.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Ma, Y., Pannicke, U., Schwarz, K., Lieber, M.R. (2004). "Hairpin opening and overhang processing by an Artemis/DNA-dependent protein kinase complex in nonhomologous end joining and V(D)J recombination". Cell. 108 (6): 781–794. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00671-2. PMID 11955432.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Wyman, C., Kanaar, R. (2006). "DNA double-strand break repair: All's well that ends well". Annual Review of Genetics. 40: 363–383. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090451. PMID 16895466.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Krangel, M.S. (2009). "Mechanics of T cell receptor gene rearrangement". Current Opinion in Immunology. 21 (2): 133–139. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2009.03.009. PMC 2676214. PMID 19362456.