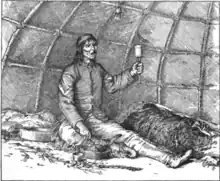

Medicine man

A medicine man or medicine woman is a traditional healer and spiritual leader who serves a community of Indigenous people of the Americas. Individual cultures have their own names, in their respective Indigenous languages, for the spiritual healers and ceremonial leaders in their particular cultures.

Cultural context

In the ceremonial context of Indigenous North American communities, "medicine" usually refers to spiritual healing. Medicine men/women should not be confused with those who employ Native American ethnobotany, a practice that is very common in a large number of Native American and First Nations households.[2][3][4]

The terms medicine people or ceremonial people are sometimes used in Native American and First Nations communities, for example, when Arwen Nuttall (Cherokee) of the National Museum of the American Indian writes, "The knowledge possessed by medicine people is privileged, and it often remains in particular families."[5]

Native Americans tend to be quite reluctant to discuss issues about medicine or medicine people with non-Indians. In some cultures, the people will not even discuss these matters with Indians from other tribes. In most tribes, medicine elders are prohibited from advertising or introducing themselves as such. As Nuttall writes, "An inquiry to a Native person about religious beliefs or ceremonies is often viewed with suspicion."[5] One example of this is the Apache medicine cord or Izze-kloth whose purpose and use by Apache medicine elders was a mystery to nineteenth century ethnologists because "the Apache look upon these cords as so sacred that strangers are not allowed to see them, much less handle them or talk about them."[6]

The 1954 version of Webster's New World Dictionary of the American Language reflects the poorly-grounded perceptions of the people whose use of the term effectively defined it for the people of that time: "a man supposed to have supernatural powers of curing disease and controlling spirits." In effect, such definitions were not explanations of what these "medicine people" are to their own communities but instead reported on the consensus of socially and psychologically remote observers when they tried to categorize the individuals. The term medicine man/woman, like the term shaman, has been criticized by Native Americans, as well as other specialists in the fields of religion and anthropology.

While non-Native anthropologists sometimes use the term shaman for indigenous healers worldwide, including the Americas, shaman is the specific name for a spiritual mediator from the Tungusic peoples of Siberia[7] and is not used in Native American or First Nations communities.

Frauds and scams

There are many fraudulent healers and scam artists who pose as Cherokee "shamans", and the Cherokee Nation has had to speak out against these people, even forming a task force to handle the issue. In order to seek help from a Cherokee medicine person a person needs to know someone in the community who can vouch for them and provide a referral. Usually one makes contact through a relative who knows the healer.[8]

See also

- Bomoh or Dukun in South-East Asia

- Cultural appropriation

- Curandero

- Folk healer

- Herbalism

- Holism

- Keewaydinoquay Peschel

- Kallawaya

- Kennekuk

- Medicine bag

- Native American ethnobotany

- Native American religion

- Plastic shaman

- Prehistoric medicine

- Quesalid

- Trance

Notes

- ↑ Fienup-Riordan, Ann. (1994). Boundaries & Passages: Rule and Ritual in Yup'ik Eskimo Oral Tradition. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, p. 206. Nushagak, located on Nushagak Bay of the Bering Sea in southwest Alaska, is part of the territory of the Yup'ik, speakers of the Central Alaskan Yup'ik language.

- ↑ Alcoze, Dr Thomas M. "Ethnobotany from a Native American Perspective: Restoring Our Relationship with the Earth Archived 4 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine" in Botanic Gardens Conservation International Volume 1 Number 19 - December 1999

- ↑ Moerman, Daniel E. (1979). "Symbols and selectivity: A statistical analysis of native american medical ethnobotany" (PDF). Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1 (2): 111–119. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(79)90002-3. hdl:2027.42/23587. PMID 94415.

- ↑ Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry, "Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Sustaining Our Lives and the Natural World" at United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Newtown Square, PA. December 2011

- 1 2 National Museum of the American Indian. Do All Indians Live in Tipis? Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2007. ISBN 978-0-06-115301-3.

- ↑ Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology (1892), Annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Issue 9, Government Printing Office, United States Government, 1892,

There is probably no more mysterious or interesting portion of the religious or 'medicinal' equipment of the Apache Indian, whether he be medicine-man or simply a member of the laity, than the 'izze-kloth' or medicine cord... the Apache look upon these cords as so sacred that strangers are not allowed to see them, much less handle them or talk about them....

- ↑ Smith, C. R. "Shamanism." Archived 12 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine Cabrillo College. (Retrieved 28 June 2011)

- ↑ "Cherokee Medicine Men and Women". cherokee.org. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Medicine man |

.svg.png.webp)