Maroteaux–Lamy syndrome

| Maroteaux–Lamy syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Mucopolysaccharidosis type VI,[1] MPS VI, or Polydystrophic dwarfism | |

.jpg.webp) | |

| A 16-year old boy with rapidly progressing MPS-VI, showing characteristic facial features and spinal deformities | |

| Symptoms | Variable. May include: Macrocephaly, Hydrocephalus, Coarse facial features, Heart valve disease, Enlarged liver and spleen, Umbilical hernia[2] |

| Usual onset | Patients are affected at birth; symptoms usually appear during early childhood |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Causes | Mutations in the ASRB gene |

| Differential diagnosis | Other mucopolysaccharidosis disorders |

| Prognosis | Reduced life expectancy |

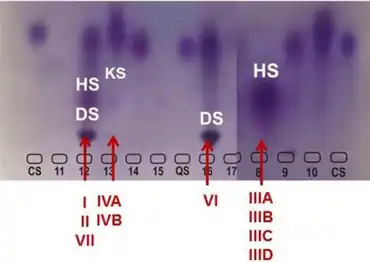

Maroteaux–Lamy syndrome, or mucopolysaccharidosis Type VI (MPS-VI), is an inherited disease caused by a deficiency in the enzyme arylsulfatase B (ARSB).[3] ASRB is responsible for the breakdown of large sugar molecules called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs, also known as mucopolysaccharides). In particular, ARSB breaks down dermatan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate. Because people with MPS-VI lack the ability to break down these GAGs, these chemicals build up in the lysosomes of cells. MPS-VI is therefore a type of lysosomal storage disease.

Signs and symptoms

.jpg.webp)

Unlike other MPS diseases, children with Maroteaux–Lamy syndrome usually have normal intelligence.[2] They share many of the physical symptoms found in Hurler syndrome. Maroteaux–Lamy syndrome has a variable spectrum of severe symptoms. Neurological complications include clouded corneas, deafness, thickening of the dura (the membrane that surrounds and protects the brain and spinal cord), and pain caused by compressed or traumatized nerves and nerve roots.

Signs are revealed early in the affected child's life, with one of the first symptoms often being a significantly prolonged age of learning how to walk. Growth begins normally, but children usually stop growing by age 8. By age 10, children often develop a shortened trunk, crouched stance, and restricted joint movement. In more severe cases, children also develop a protruding abdomen and forward-curving spine. Skeletal changes, particularly in the pelvis, are progressive and limit movement. Many children also have umbilical hernia or inguinal hernias. Nearly all children have some form of heart disease, usually involving the heart valves.[4]

Genetics

This disorder is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. People with two working copies of the gene are unaffected. People with one working copy are genetic carriers of Maroteaux-Lamy Syndrome. They have no symptoms but may pass down the defective gene to their children. People with two defective copies will suffer from MPS-VI.[5]

Diagnosis

A urinalysis will show elevated levels of dermatan sulfate in the urine. A blood sample may be taken to assess the level of ASRB activity. Dermal fibroblast cells may also be examined for ASRB activity. Molecular genetic testing can give information about the specific mutation causing MPS-VI, but it is only available at specialized laboratories.[5]

Treatment

The treatment of Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome is symptomatic and individually tailored. A variety of specialists may be needed. In 2005, the FDA approved the orphan drug galsulfase (Naglazyme) for the treatment of Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome. Galsulfase is an enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) in which the missing ASRB enzyme is replaced with a recombinant version.

In addition to ERT, various procedures can alleviate the symptoms of MPS-VI. Surgery may be necessary to treat abnormalities such as carpal tunnel syndrome, skeletal malformations, spinal cord compression, hip degeneration, and hernias. Some patients may need heart valve replacement. It may be necessary to remove the tonsils and/or adenoids. Severe tracheomalacia may require surgery. Physical therapy and exercise may improve joint stiffness.

Hydrocephalus may be treated by the insertion of a shunt to drain excess cerebrospinal fluid. A corneal transplantation can be performed for individuals with severe corneal clouding. A myringotomy, in which a small incision is made in the eardrum, may be helpful for patients with fluid accumulation in the ears. Hearing aids may be useful, and speech therapy may help children with hearing loss communicate more effectively.

Certain medications can be used to treat heart abnormalities, asthma-like episodes, and chronic infections associated with MPS-VI. Anti-inflammatory medications may be of benefit. Respiratory insufficiency may require treatment with supplemental oxygen. Aggressive management of airway secretions is necessary as well. Sleep apnea may be treated with a CPAP or BPAP device.[5]

Prognosis

The life expectancy of individuals with MPS VI varies depending on the severity of symptoms. Without treatment, some individuals may survive through late childhood or early adolescence. People with milder forms of the disorder usually live into adulthood, although they may have reduced life expectancy. Heart disease and airway obstruction are major causes of death in people with Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome.[2]

Epidemiology

Males and females are affected equally.[5] Studies have shown a birth prevalence between 1 in 43,261 and 1 in 1,505,160 live births. These numbers are likely an underestimate of the true number of cases, because newborn screening for MPS-VI is not widely available. Although studies have not revealed an ethnic predisposition, certain groups with a high degree of consanguinity have a higher prevalence of MPS-VI. For example, one study of a population of Turkish immigrants in Germany revealed that this group had a rate of 1 in 43,261; this was approximately ten times higher than the rate of MPS-VI in non-Turkish Germans. In different populations worldwide, MPS-VI made up between 2 and 18.5% of all MPS disorders.[6]

History

It is named after Pierre Maroteaux (1926–2019) and his mentor Maurice Emil Joseph Lamy (1895–1975), both French physicians.[7][8]

Society and culture

Keenan Cahill is a YouTuber with Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome.[9]

Isabel Bueso, a Guatemalan woman with Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome who has been receiving treatment at UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital, was at risk of deportation from the United States after the Trump Administration ended the deferred action program in August 2019.[10] In December 2019, she was granted another deferral of two years.[11]

See also

- Hurler syndrome (MPS I)

- Hunter syndrome (MPS II)

- Sanfilippo syndrome (MPS III)

- Morquio syndrome (MPS IV)

References

- ↑ Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- 1 2 3 "Mucopolysaccharidosis type VI". United States National Library of Medicine. 11 June 2019. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ↑ Garrido E, Cormand B, Hopwood JJ, Chabás A, Grinberg D, Vilageliu L (July 2008). "Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome: functional characterization of pathogenic mutations and polymorphisms in the arylsulfatase B gene". Mol. Genet. Metab. 94 (3): 305–12. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.02.012. PMID 18406185.

- ↑ "Mucopolysaccharidoses Fact Sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 13 May 2019. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 Giugliani, Roberto (2017). "Maroteaux Lamy Syndrome". National Organization for Rare Disorders. Archived from the original on 8 February 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ↑ Valayannopoulos, Vassili; Nicely, Helen; Harmatz, Paul; Turbeville, Sean (12 Apr 2010). "Mucopolysaccharidosis VI". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 5 (5): 5. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-5-5. PMC 2873242. PMID 20385007.

- ↑ synd/1619 at Who Named It?

- ↑ MAROTEAUX P, LEVEQUE B, MARIE J, LAMY M (September 1963). "A New Dysostosis with Urinary Elimination of Chondroitin Sulfate B". Presse Med (in français). 71: 1849–52. PMID 14091597.

- ↑ Cary, Joan (5 May 2011). "Elmhurst teen a YouTube lip-syncing sensation". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ↑ "Disabled Concord woman from Guatemala fights to stay in the U.S. - SFChronicle.com". www.sfchronicle.com. 2019-09-06. Archived from the original on 2019-09-07. Retrieved 2019-09-06.

- ↑ "Critically-ill Concord woman slated for deportation will remain in the U.S." SFChronicle.com. 2019-12-09. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |