Oral cancer

| Oral cancer | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Cancer of the lip, oral cavity and pharynx, mouth cancer, cancer or the lips, oral cavity and pharynx[1] | |

| |

| Oral cancer on the side of the tongue, a common site along with the floor of the mouth | |

| Specialty | Oncology, ENT surgery, oral and maxillofacial surgery |

| Symptoms | Persistent rough white or red patch in the mouth lasting longer than 2 weeks, ulceration, lumps/bumps in the neck, pain, loose teeth, difficulty swallowing |

| Risk factors | Smoking, alcohol, HPV infection, sun exposure, chewing tobacco |

| Diagnostic method | Tissue biopsy |

| Differential diagnosis | Non-squamous cell carcinoma oral cancer, salivary gland tumors, benign mucosal disease |

| Prevention | Avoiding risk factors,[2] HPV vaccination[3] |

| Treatment | Surgery, radiation, chemotherapy |

| Prognosis | Five-year survival ~ 65% (US 2015)[4] |

| Frequency | 355,000 new cases (2018)[5] |

| Deaths | 177,000 (2018)[5] |

Oral cancer, also known as mouth cancer, is cancer of the lining of the lips, mouth, or upper throat.[6] In the mouth, it most commonly starts as a painless white patch, that thickens, develops red patches, an ulcer, and continues to grow. When on the lips, it commonly looks like a persistent crusting ulcer that does not heal, and slowly grows.[7] Other symptoms may include difficult or painful swallowing, new lumps or bumps in the neck, a swelling in the mouth, or a feeling of numbness in the mouth or lips.[8]

Risk factors include tobacco and alcohol use.[9][10] Those who use both alcohol and tobacco have a 15 times greater risk of oral cancer than those who use neither.[11] Other risk factors include HPV infection,[12] chewing paan,[13] and sun exposure on the lower lip.[14] Oral cancer is a subgroup of head and neck cancers.[6] Diagnosis is made by biopsy of the concerning area, followed by investigation with CT scan, MRI, PET scan, and examination to determine if it has spread to distant parts of the body.

Oral cancer can be prevented by avoiding tobacco products, limiting alcohol use, sun protection on the lower lip, HPV vaccination, and avoidance of paan. Treatments used for oral cancer can include a combination of surgery (to remove the tumor and regional lymph nodes), radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or targeted therapy. The types of treatments will depend on the size, locations, and spread of the cancer taken into consideration with the general health of the person.[7]

In 2018, oral cancer occurred globally in about 355,000 people, and resulted in 177,000 deaths.[5] Between 1999 and 2015 in the United States, the rate of oral cancer increased 6% (from 10.9 to 11.6 per 100,000). Deaths from oral cancer during this time decreased 7% (from 2.7 to 2.5 per 100,000).[15] Oral cancer has an overall 5 year survival rate of 65% in the United States as of 2015.[4] This varies from 84% if diagnosed when localized, compared to 66% if it has spread to the lymph nodes in the neck, and 39% if it has spread to distant parts of the body.[4] Survival rates also are dependent on the location of the disease in the mouth.[16]

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of oral cancer depend on the location of the tumor but are generally thin, irregular, white patches in the mouth. They can also be a mix of red and white patches (mixed red and white patches are much more likely to be cancerous when biopsied). The classic warning sign is a persistent rough patch with ulceration, and a raised border that is minimally painful. On the lip, the ulcer is more commonly crusting and dry, and in the pharynx it is more commonly a mass. It can also be associated with a white patch, loose teeth, bleeding gums, persistent ear ache, a feeling of numbness in the lip and chin, or swelling.[17]

When the cancer extends to the throat, there can also be difficulty swallowing, painful swallowing, and an altered voice.[18] Typically, the lesions have very little pain until they become larger and then are associated with a burning sensation.[19] As the lesion spreads to the lymph nodes of the neck, a painless, hard mass will develop. If it spreads elsewhere in the body, general aches can develop, most often due to bone metastasis.[19]

.jpg.webp) Carcinoma of the tongue

Carcinoma of the tongue.jpg.webp) Inner lip cancer

Inner lip cancer.jpg.webp) Alveolar (gum) cancer

Alveolar (gum) cancer Swelling of the right neck from the spread of oral cancer.

Swelling of the right neck from the spread of oral cancer. Ulceration on the left lower lip caused by cancer

Ulceration on the left lower lip caused by cancer

Causes

Oral squamous cell carcinoma is a disease of environmental factors, the greatest of which is tobacco. Like all environmental factors, the rate at which cancer will develop is dependent on the dose, frequency and method of application of the carcinogen (the substance that is causing the cancer).[20] Aside from cigarette smoking, other carcinogens for oral cancer include alcohol, viruses (particularly HPV 16 and 18), radiation, and UV light.[7]

Tobacco

Tobacco is the greatest single cause of oral and pharyngeal cancer. It is a known multi-organ carcinogen, that has a synergistic interaction with alcohol to cause cancers of the mouth and pharynx by directly damaging cellular DNA.[20] Tobacco is estimated to increase the risk of oral cancer by 3.4[20]–6.8[9] and is responsible for approximately 40% of all oral cancers.[21]

Alcohol

Some studies in Australia, Brazil and Germany pointed to alcohol-containing mouthwashes as also being potential causes. The claim was that constant exposure to these alcohol-containing rinses, even in the absence of smoking and drinking, leads to significant increases in the development of oral cancer. However, studies conducted in 1985,[22] 1995,[23] and 2003[24] summarize that alcohol-containing mouth rinses are not associated with oral cancer. In a March 2009 brief, the American Dental Association said "the available evidence does not support a connection between oral cancer and alcohol-containing mouthrinse".[25] A 2008 study suggests that acetaldehyde (a breakdown product of alcohol) is implicated in oral cancer,[26][27] but this study specifically focused on abusers of alcohol and made no reference to mouthwash.

Human papillomavirus

Infection with human papillomavirus (HPV), particularly type 16 (there are over 180 types), is a known risk factor and independent causative factor for oral cancer.[28] A fast-growing segment of those diagnosed does not present with the historic stereotypical demographics. Historically that has been people over 50, blacks over whites 2 to 1, males over females 3 to 1, and 75% of the time people who have used tobacco products or are heavy users of alcohol. This new and rapidly growing subpopulation between 30 and 50 years old,[29] is predominantly nonsmoking, white, and males slightly outnumber females. Recent research from multiple peer-reviewed journal articles indicates that HPV16 is the primary risk factor in this new population of oral cancer victims. HPV16 (along with HPV18) is the same virus responsible for the vast majority of all cervical cancers and is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the US. Oral cancer in this group tends to favor the tonsil and tonsillar pillars, base of the tongue, and the oropharynx. Recent data suggest that individuals who develop the disease from this particular cause have a significant survival advantage,[30] as the disease responds better to radiation treatments than tobacco caused disease.

Betel nut

Chewing betel, paan and Areca is known to be a strong risk factor for developing oral cancer even in the absence of tobacco. It increases the rate of oral cancer 2.1 times, through a variety of genetic and related effects through local irritation of the mucous membrane cells, particularly from the areca nut and slaked lime.[20] In India where such practices are common, oral cancer represents up to 40% of all cancers, compared to just 4% in the UK.

Stem cell transplantation

People after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) are at a higher risk for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Post-HSCT oral cancer may have more aggressive behavior with poorer prognosis, when compared to oral cancer in people not treated with HSCT.[31] This effect is supposed to be owing to the continuous lifelong immune suppression and chronic oral graft-versus-host disease.[31]

Premalignant lesions

A premalignant (or precancerous) lesion is defined as "a benign, morphologically altered tissue that has a greater than normal risk of malignant transformation." There are several different types of premalignant lesion that occur in the mouth. Some oral cancers begin as white patches (leukoplakia), red patches (erythroplakia) or mixed red and white patches (erythroleukoplakia or "speckled leukoplakia"). Other common premalignant lesions include oral submucous fibrosis and actinic cheilitis.[32] In the Indian subcontinent oral submucous fibrosis is very common due to betel nut chewing. This condition is characterized by limited opening of mouth and burning sensation on eating of spicy food. This is a progressive lesion in which the opening of the mouth becomes progressively limited, and later on even normal eating becomes difficult. It occurs almost exclusively in India and Indian communities living abroad.

Pathophysiology

Oral squamous cell carcinoma is the end product of an unregulated proliferation of mucous basal cells. A single precursor cell is transformed into a clone consisting of many daughter cells with an accumulation of altered genes called oncogenes. What characterizes a malignant tumor over a benign one is its ability to metastasize. This ability is independent of the size or grade of the tumor (often seemingly slow growing cancers like the adenoid cystic carcinoma can metastasis widely). It is not just rapid growth that characterizes a cancer, but their ability to secrete enzymes, angiogeneic factors, invasion factors, growth factors and many other factors that allow it to spread.[7]

Diagnosis

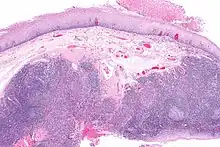

Diagnosis of oral cancer is completed for (1) initial diagnosis, (2) staging, and (3) treatment planning. A complete history, and clinical examination is first completed, then a wedge of tissue is cut from the suspicious lesion for tissue diagnosis. This might be done with scalpel biopsy, punch biopsy, fine or core needle biopsy. In this procedure, the surgeon cuts all, or a piece of the tissue, to have it examined under a microscope by a pathologist.[33] Brush biopsies are not considered accurate for the diagnosis of oral cancer.[34]

With the first biopsy, the pathologist will provide a tissue diagnosis (e.g. squamous cell carcinoma), and classify the cell structure. They may add additional information that can be used in staging, and treatment planning, such as the mitotic rate, the depth of invasion, and the HPV status of the tissue.

After the tissue is confirmed cancerous, other tests will be completed to:

- better assess the size of the lesion (CT scan, MRI or PET scan with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)),[33]: 143

- look for other cancers in the upper aerodigestive tract (which may include endoscopy of the nasal cavity/pharynx, larynx, bronchus, and esophagus called panendoscopy or quadoscopy),

- spread to the lymph nodes (CT scan) or

- spread to other parts of the body (chest X-ray, nuclear medicine).

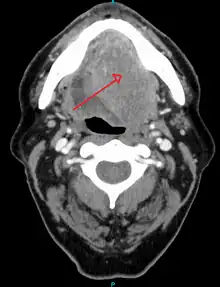

Other, more invasive tests, may also be completed such as fine needle aspiration, biopsy of lymph nodes, and sentinel node biopsy. When the cancer has spread to lymph nodes, their exact location, size, and spread beyond the capsule (of the lymph nodes) needs to be determined, as each can have a significant impact on treatment and prognosis. Small differences in the pattern of lymph node spread, can have a significant impact on treatment and prognosis. Panendoscopy may be recommended, because the tissues of the entire upper aerodigestive tract are generally affected by the same carcinogens, so other primary cancers are a common occurrence.[35][36]

From these collective findings, taken in consideration with the health and desires of the person, the cancer team develops a plan for treatment. Since most oral cancers require surgical removal, a second set of histopathologic tests will be completed on any tumor removed to determine the prognosis, need for additional surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy, or other interventions.

Classification

Oral cancer is a subgroup of head and neck cancers which includes those of the oropharynx, larynx, nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, salivary glands, and thyroid gland. Oral melanoma, while part of head and neck cancers is considered separately.[6] Other cancers can occur in the mouth (such as bone cancer, lymphoma, or metastatic cancers from distant sites) but are also considered separately from oral cancers.[6]

Staging

Oral cancer staging is an assessment of the degree of spread of the cancer from its original source.[37] It is one of the factors affecting both the prognosis and the potential treatment of oral cancer.[37]

The evaluation of squamous cell carcinoma of the mouth and pharynx staging uses the TNM classification (tumor, node, metastasis). This is based on the size of the primary tumor, lymph node involvement, and distant metastasis.[38]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TMN evaluation allows the person to be classified into a prognostic staging group;[38]

| When T is... | And N is... | And M is... | Then the stage group is... |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tis | N0 | M0 | 0 |

| T1 | N0 | M0 | I |

| T2 | N0 | M0 | II |

| T3 | N0 | M0 | III |

| T1,T2,T3 | N1 | M0 | III |

| T4a | N0,N1 | M0 | IVA |

| T1,T2,T3,T4a | N2 | M0 | IVA |

| Any T | N3 | M0 | IVB |

| T4b | Any N | M0 | IVB |

| Any T | Any N | M1 | IVC |

Screening

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) in 2013 stated evidence was insufficient to determine the balance of benefits and harms of screening for oral cancer in adults without symptoms by primary care providers.[39] The American Academy of Family Physicians comes to similar conclusions while the American Cancer Society recommends that adults over 20 years who have periodic health examinations should have the oral cavity examined for cancer.[39] The American Dental Association recommends that providers remain alert for signs of cancer during routine examinations.[39]

There are a variety of screening devices, however, there is no evidence that routine use of these devices in general dental practice is helpful.[40] However, there are compelling reasons to be concerned about the risk of harm this device may cause if routinely used in general practice. Such harms include false positives, unnecessary surgical biopsies and a financial burden. Micronuclei assays can help in early detection of pre-malignant and malignant lesions, thereby improving survival and reducing morbidity associated with treatment.

There has also been research showing potential in using oral cytology as a diagnostic test for oral cancer instead of traditional biopsy techniques; in oral cytology, a brush is used to take some cells from the suspected lesion/area and these are sent to a laboratory for examination.[41] This can be much less invasive and painful than a scalpel biopsy for the patient. However, a Cochrane review concluded that there needs to be further research before oral cytology can be considered as an effective routine screening tool when compared to biopsies.[41]

Management

Oral cancer (squamous cell carcinoma) is usually treated with surgery alone, or in combination with adjunctive therapy, including radiation, with or without chemotherapy.[33]: 602 With small lesions (T1), surgery or radiation have similar control rates, so the decision about which to use is based on functional outcome, and complication rates.[33]

Surgery

In most centres, removal of squamous cell carcinoma from the oral cavity and neck is achieved primarily through surgery. This also allows a detailed examination of the tissue for histopathologic characteristics, such as depth, and spread to lymph nodes that might require radiation or chemotherapy. For small lesions (T1–2), access to the oral cavity is through the mouth. When the lesion is larger, involves the bone of the maxilla or mandible, or access is limited due to mouth opening, the upper or lower lip is split, and the cheek pulled back to give greater access to the mouth.[33] When the tumor involves the jaw bone, or when surgery or radiation will cause severe limited mouth opening, part of the bone is also removed with the tumor.

Management of the neck

Spread of cancer from the oral cavity to the lymph nodes of the neck has a significant effect on survival. Between 60–70% of people with early stage oral cancer will have no lymph node involvement of the neck clinically, but 20–30% of those people (or up to 20% of all those affected) will have clinically undetectable spread of cancer to the lymph nodes of the neck (called occult disease).

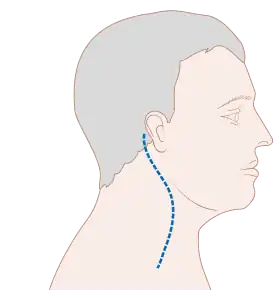

The management of the neck is crucial, since spread to it reduces the chance of survival by 50%.[42] If there is evidence of lymph node involvement of the neck, during the diagnostic phase, then a modified radical neck dissection is generally performed. Where the neck lymph nodes have no evidence of involvement clinically, but the oral cavity lesion is high risk for spread (e.g. T2 or above lesions), then a neck dissection of the lymph nodes above the level of the omohyoid muscle may be completed. When disease if found in the nodes after removal (but not seen clinically) the recurrence rates is 10–24%. If post-operative radiation is added, the failure rate is 0–15%. When lymph nodes are clinically found during the diagnosis phase, and radiation is added post-operative, disease control is >80%.[43]

Radiotherapy and chemotherapy

.jpg.webp)

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are most often used, as an adjunct to surgery, to control oral cancer that is greater than stage 1, or has spread to either regional lymph nodes or other parts of the body.[33] Radiotherapy alone can be used instead of surgery, for very small lesions, but is generally used as an adjunct when lesions are large, cannot be completely removed, or have spread to the lymph nodes of the neck. Chemotherapy is useful in oral cancers when used in combination with other treatment modalities such as radiation therapy but it is not used alone as a monotherapy. When a cure is unlikely, it can also be used to extend life and can be considered palliative but not curative care.[44]

Monoclonal antibody therapy (with agents such as cetuximab) have been shown to be effective in the treatment of squamous cell head and neck cancers, and are likely to have an increasing role in the future management of this condition when used in conjunction with other established treatment modalities, although it is not a replacement for chemotherapy in head and neck cancers.[45][44] Likewise, molecularly targeted therapies and immunotherapies maybe be effective for the treatment of oral and oropharyngeal cancers. Adding epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody (EGFR mAb) to standard treatment may increase survival, keeping the cancer limited to that area of the body and may decrease reappearance of the cancer.[45]

Rehabilitation

Following treatment, rehabilitation may be necessary to improve movement, chewing, swallowing, and speech. Speech and language pathologists may be involved at this stage. Treatment of oral cancer will usually be by a multidisciplinary team, with treatment professionals from the realms of radiation, surgery, chemotherapy, nutrition, dentistry, and even psychology all possibly involved with diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation, and care. Due to the location of oral cancer, there may be a period where the person requires a tracheotomy and feeding tube.

Prognosis

Survival rates for oral cancer depend on the precise site and the stage of the cancer at diagnosis. Overall, 2011 data from the SEER database shows that survival is around 57% at five years when all stages of initial diagnosis, all genders, all ethnicities, all age groups, and all treatment modalities are considered. Survival rates for stage 1 cancers are approximately 90%, hence the emphasis on early detection to increase survival outcome for people. Similar survival rates are reported from other countries such as Germany.[46]

Epidemiology

Globally, it newly occurred in about 355,000 people and resulted in 177,000 deaths in 2018.[5] Of these 355,000, about 246,000 are males and 108,000 are females.[5]

In 2013, oral cancer resulted in 135,000 deaths, up from 84,000 deaths in 1990.[47] Oral cancer occurs more often in people from lower and middle income countries.[48]

Europe

Europe places second-highest after Southeast Asia among all continents for age-standardised rate (ASR) specific to oral and oropharyngeal cancer. It is estimated that there were 61,400 cases of oral and lip cancer within Europe in 2012. Hungary recorded the highest number of mortality and morbidity due to oral and pharyngeal cancer among all European countries while Cyprus reported the lowest numbers [49]

United Kingdom

British Cancer Research found 2,386 deaths due to oral cancer in 2014; while most oral cancer cases are diagnosed in older adults between 50-74 years old, this condition can affect the young as well;[50] 6% of people affected by oral cancer are under 45 years of age.[51] The UK is 16th-lowest for males and 11th-highest for females for oral cancer incidence among Europe. Additionally, there is a regional variability within the UK, with Scotland and northern England having higher rates than southern England. The same analysis applies to lifetime risk of developing oral cancer, as in Scotland it is 1.84% in males and 0.74% in females, higher than the rest of the UK, being 1.06% and 0.48%, respectively.

Oral cancer is the sixteenth most common cancer in the UK (around 6,800 people were diagnosed with oral cancer in the UK in 2011), and it is the nineteenth-most -common cause of cancer death (around 2,100 people died from the disease in 2012).[51]

Northern Europe

The highest incidence of oral and pharyngeal cancer was recorded in Denmark, with age-standardised rates per 100,000 of 13.0, followed by Lithuania (9.9) and the United Kingdom (9.8).[49] Lithuania reported the highest incidence in men while Denmark reported the highest in women. The highest rates for mortality in 2012 were reported in Lithuania (7.5), Estonia (6.0), and Latvia (5.4).[49] Incidence of oral cancer in young adults (ages 20-39 years old) in Scandinavia has reportedly risen approximately 6-fold between 1960-1994[52] The high incidence rate of oral and pharyngeal cancer in Denmark could be attributed to their higher alcohol intake than citizens of other Scandinavian countries and low intake of fruits and vegetables in general.

Eastern Europe

Hungary (23.3), Slovakia (16.4), and Romania (15.5) reported the highest incidences of oral and pharyngeal cancer.[49] Hungary also recorded the highest incidence in both genders as well as the highest mortality rates in Europe.[49] It is ranked third globally for cancer mortality rates.[53] Cigarette smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, inequalities in the care received by people with cancer, and gender-specific systemic risk factors have been determined as the leading causes for the high morbidity and mortality rates in Hungary.[54][55][56][57]

Western Europe

The incidence rates of oral cancer in western Europe found France, Germany and Belgium to be highest. The ASRs (per 100,000) were 15.0, 14.6, and 14.1, respectively. When filtered by gender category, the same countries rank top 3 for male, however, in different order of Belgium (21.9), Germany (23.1), and France (23.1). France, Belgium, and the Netherlands ranks highest for females, with ASRs 7.6, 7.0, and 7.0, respectively.[49]

Southern Europe

Incidence of oral and oropharyngeal cancers were recorded, finding Portugal, Croatia and Serbia to have highest rates (ASR per 100,000). These values are 15.4, 12, and 11.7, respectively.

United States

In 2011, close to 37,000 Americans are projected to be diagnosed with oral or pharyngeal cancer. 66% of the time, these will be found as late stage three and four disease. It will cause over 8,000 deaths. Of those newly diagnosed, only slightly more than half will be alive in five years. Similar survival estimates are reported from other countries. For example, five-year relative survival for oral cavity cancer in Germany is about 55%.[46] In the US oral cancer accounts for about 8 percent of all malignant growths.

Oral cancers overall risk higher in black males opposed to white males, however specific oral cancers-such as of the lip, have a higher risk in white males opposed to black males. Overall, rates of oral cancer between gender groups (male and female) seem to be decreasing, according to data from 3 studies.[58]

Of all the cancers, oral cancer attributes to 3% in males, opposed to 2% in women. New cases of oral cancer in US as of 2013, approximated almost 66,000 with almost 14000 attributed from tongue cancer, and nearly 12000 from the mouth, and the remainder from the oral cavity and pharynx. In the previous year, 1.6% of lip and oral cavity cancers were diagnosed, where the age-standardised incidence rate (ASIR) across all geographic regions of United States of America estimates at 5.2 per 100,000 population.[59] It is the eleventh-most-common cancer in the United States among males while in Canada and Mexico it is the twelfth and thirteenth-most-common cancer respectively. The ASIR for lip and oral cavity cancer among men in Canada and Mexico is 4.2 and 3.1, respectively.[59]

South America

The ASIR across all geographic regions of South America as of 2012 sits at 3.8 per 100,000 population where approximately 6,046 deaths have occurred due to lip and oral cavity cancer, where the age-standardized mortality rate remains at 1.4.[60]

In Brazil, however, lip and oral cavity cancer is the 7th most common cancer, with an estimated 6,930 new cases diagnosed in the year 2012. This number is rising and has an overall higher ASIR at 7.2 per 100,000 population whereby an approx 3000 deaths have occurred [60]

Rates are increasing across both males and females. As of 2017, almost 50000 new cases of oropharyngeal cancers will be diagnosed, with incidence rates being more than twice as high in men than women.[60]

Asia

Oral cancer is one of the most-common types of cancer in Asia due to its association with smoking (tobacco, bidi), betel quid and alcohol consumption. Regionally incidence varies with highest rates in South Asia, particularly Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Philippines, and Sri Lanka.[61][62] In South East Asia and Arab countries, although the prevalence is not as high, estimated incidences of oral cancer ranged from 1.6 to 8.6/ 100,000 and 1.8 to 2.13/ 100,000 respectively.[63][64] According to GLOBOCAN 2012, the estimated age-standardised rates of cancer incidence and mortality was higher in males than females. However, in some areas, specifically South East Asia, similar rates were recorded for both genders.[63] The average age of those diagnosed with oral sarcoma cell carcinoma is approximately 51–55.[62] In 2012, there were 97,400 deaths recorded due to oral cancer.[65]

India

Oral cancer is the third-most-common form of cancer in India with over 77 000 new cases diagnosed in 2012 (2.3:1 male to female ratio).[66] Studies estimate over five deaths per hour.[67] One of the reasons behind such high incidence might be popularity of betel and areca nuts, which are considered to be risk factors for development of oral cavity cancers.[68]

Africa

There is limited data for the prevalence of oral cancer in Africa. The following rates describe the number of new cases (for incidence rates) or deaths (for mortality rates) per 100 000 individuals per year.[65]

The incidence rate of oral cancer is 2.6 for both sexes. The rate is higher in males at 3.3 and lower in females at 2.0.[65]

The mortality rate is lower than the incidence rate at 1.6 for both sexes. The rate is again higher for males at 2.1 and lower for females at 1.3.[65]

Australia

The following rates describe the number of new cases or deaths per 100 000 individuals per year. The incidence rate of oral cancer is 6.3 for both sexes; this is higher in males at 6.8–8.8 and lower in females at 3.7–3.9.[69] The mortality rate is significantly lower than the incidence rate at 1.0 for both sexes. The rate is higher in males at 1.4 and lower in females at 0.6.[70] Table 1 provides age-standardised incidence and mortality rates for oral cancer based on the location in the mouth. The location ‘other mouth’ refers to the buccal mucosa, the vestibule and other unspecified parts of the mouth. The data suggests lip cancer has the highest incidence rate while gingival cancer has the lowest rate overall. In terms of mortality rates, oropharyngeal cancer has the highest rate in males and tongue cancer has the highest rate in females. Lip, palatal and gingival cancer have the lowest mortality rates overall.[70]

| Location | Incidence per 100 000 individuals per year | Mortality per 100 000 individuals per year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both sexes | Males | Females | Both sexes | Males | Females | |

| Lip | 5.3 | 8.4 | 2.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Tongue | 2.4 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.4 |

| Gingivae | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Floor of mouth | 0.9 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Palate | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Other Mouth | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Major salivary glands | 1.2 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Oropharynx | 1.9 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.3 |

Other animals

Oral cancers are the fourth most common type seen in other animals in veterinary medicine.[71]

References

- ↑ Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. (December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMID 23245604. S2CID 1541253. Archived from the original on 2020-05-19. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ↑ "Oral Cavity, Pharyngeal, and Laryngeal Cancer Prevention". National Cancer Institute. 1 January 1980. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ↑ "HPV Vaccine May Prevent Oral HPV Infection". National Cancer Institute. 5 June 2017. Archived from the original on 8 January 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Cancer Stat Facts: Oral Cavity and Pharynx Cancer". NCI. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Cancer today". gco.iarc.fr. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 Edge SB, et al. (American Joint Committee on Cancer) (2010). AJCC cancer staging manual (7th ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN 9780387884400. OCLC 316431417.

- 1 2 3 4 Marx RE, Stern D (2003). Oral and maxillofacial pathology : a rationale for diagnosis and treatment. Stern, Diane. Chicago: Quintessence Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0867153903. OCLC 49566229.

- ↑ "Head and Neck Cancers". CDC. 2019-01-17. Archived from the original on 2020-01-22. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- 1 2 Gandini S, Botteri E, Iodice S, Boniol M, Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Boyle P (January 2008). "Tobacco smoking and cancer: a meta-analysis". International Journal of Cancer. 122 (1): 155–64. doi:10.1002/ijc.23033. PMID 17893872. S2CID 27018547.

- ↑ Goldstein BY, Chang SC, Hashibe M, La Vecchia C, Zhang ZF (November 2010). "Alcohol consumption and cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx from 1988 to 2009: an update". European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 19 (6): 431–65. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32833d936d. PMC 2954597. PMID 20679896.

- ↑ admin. "The Tobacco Connection". The Oral Cancer Foundation. Archived from the original on 2017-11-09. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- ↑ Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, Franceschi S (February 2005). "Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 14 (2): 467–75. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0551. PMID 15734974.

- ↑ Goldenberg D, Lee J, Koch WM, Kim MM, Trink B, Sidransky D, Moon CS (December 2004). "Habitual risk factors for head and neck cancer". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 131 (6): 986–93. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2004.02.035. PMID 15577802. S2CID 34356067.

- ↑ Kerawala C, Roques T, Jeannon JP, Bisase B (May 2016). "Oral cavity and lip cancer: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 130 (S2): S83–S89. doi:10.1017/S0022215116000499. PMC 4873943. PMID 27841120.

- ↑ "USCS Data Visualizations". gis.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-01-25. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- ↑ "Survival Rates for Oral Cavity and Oropharyngeal Cancer". www.cancer.org. Archived from the original on 2019-02-14. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- ↑ Ravikiran Ongole, Praveen B N, ed. (2014). Textbook of Oral Medicine, Oral Diagnosis and Oral Radiology. Elsevier India. p. 387. ISBN 978-8131230916. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ↑ "Symptoms of oral cancer—Canadian Cancer Society". www.cancer.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-08-14. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- 1 2 Markopoulos AK (2012-08-10). "Current aspects on oral squamous cell carcinoma". The Open Dentistry Journal. 6 (1): 126–30. doi:10.2174/1874210601206010126. PMC 3428647. PMID 22930665.

- 1 2 3 4 IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (2012). "Personal habits and indoor combustions. Volume 100 E. A review of human carcinogens". IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. 100 (Pt E): 1–538. PMC 4781577. PMID 23193840.

- ↑ Cancer Care Ontario (2014). "Cancer Risk Factors in Ontario: Tobacco" (PDF). www.cancercare.on.ca. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-28. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ↑ Mashberg A, Barsa P, Grossman ML (May 1985). "A study of the relationship between mouthwash use and oral and pharyngeal cancer". Journal of the American Dental Association. 110 (5): 731–4. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1985.0422. PMID 3859544.

- ↑ Elmore JG, Horwitz RI (September 1995). "Oral cancer and mouthwash use: evaluation of the epidemiologic evidence". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 113 (3): 253–61. doi:10.1016/S0194-5998(95)70114-1. PMID 7675486. S2CID 20725009.

- ↑ Cole P, Rodu B, Mathisen A (August 2003). "Alcohol-containing mouthwash and oropharyngeal cancer: a review of the epidemiology". Journal of the American Dental Association. 134 (8): 1079–87. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0322. PMID 12956348.

- ↑ Science brief on alcohol-containing mouthrinses and oral cancer, Archived March 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine American Dental Association, March 2009

- ↑ Warnakulasuriya S, Parkkila S, Nagao T, Preedy VR, Pasanen M, Koivisto H, Niemelä O (March 2008). "Demonstration of ethanol-induced protein adducts in oral leukoplakia (pre-cancer) and cancer". Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 37 (3): 157–65. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00605.x. PMID 18251940.

- ↑ Alcohol and oral cancer research breakthrough Archived May 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Fakhry C (October 2015). "Epidemiology of Human Papillomavirus-Positive Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 33 (29): 3235–42. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6995. PMC 4979086. PMID 26351338.

- ↑ Martín-Hernán F, Sánchez-Hernández JG, Cano J, Campo J, del Romero J (May 2013). "Oral cancer, HPV infection and evidence of sexual transmission". Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 18 (3): e439-44. doi:10.4317/medoral.18419. PMC 3668870. PMID 23524417.

- ↑ "HPV-Positive Tumor Status Indicates Better Survival in Patients with Oropharyngeal Cancer—MD Anderson Cancer Center". www.mdanderson.org. Archived from the original on 2018-10-05. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- 1 2 Elad S, Zadik Y, Zeevi I, Miyazaki A, de Figueiredo MA, Or R (December 2010). "Oral cancer in patients after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: long-term follow-up suggests an increased risk for recurrence". Transplantation. 90 (11): 1243–4. doi:10.1097/TP.0b013e3181f9caaa. PMID 21119507.

- ↑ Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE (2002). Oral & maxillofacial pathology (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 337, 345, 349, 353. ISBN 978-0721690032.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gullane P (2016). Sataloff's Comprehensive Textbook of Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery: Head and Neck Surgery. Vol. 5. New Delhi, India: The Health Sciences Publisher. p. 600. ISBN 978-93-5152-458-8.

- ↑ H Alsarraf A, Kujan O, Farah CS (February 2018). "The utility of oral brush cytology in the early detection of oral cancer and oral potentially malignant disorders: A systematic review". Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 47 (2): 104–116. doi:10.1111/jop.12660. PMID 29130527. S2CID 46832488.

- ↑ Levine B, Nielsen EW (August 1992). "The justifications and controversies of panendoscopy--a review". Ear, Nose, & Throat Journal. 71 (8): 335–40, 343. doi:10.1177/014556139207100802. PMID 1396181. S2CID 25921527.

- ↑ Clayburgh DR, Brickman D (January 2017). "Is esophagoscopy necessary during panendoscopy?". The Laryngoscope. 127 (1): 2–3. doi:10.1002/lary.25532. PMID 27774605. S2CID 19124543.

- 1 2 Connolly JL, Goldsmith JD, Wang HH, et al. (2010). "37: Principles of Cancer Pathology". Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine (8th ed.). People's Medical Publishing House. ISBN 978-1-60795-014-1.

- 1 2 3 4 "AJCC Cancer Staging Form Supplement. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, eighth Edition Update 05 June 2018" (PDF). www.cancerstaging.org. 5 June 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Final Recommendation Statement: Oral Cancer: Screening—US Preventive Services Task Force". www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org. November 2013. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ↑ Brocklehurst P, Kujan O, O'Malley LA, Ogden G, Shepherd S, Glenny AM (November 2013). "Screening programmes for the early detection and prevention of oral cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD004150. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004150.pub4. PMID 24254989.

- 1 2 Macey R, Walsh T, Brocklehurst P, Kerr AR, Liu JL, Lingen MW, et al. (May 2015). "Diagnostic tests for oral cancer and potentially malignant disorders in patients presenting with clinically evident lesions". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD010276. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010276.pub2. PMC 7087440. PMID 26021841.

- ↑ Robbins KT, Ferlito A, Shah JP, Hamoir M, Takes RP, Strojan P, et al. (March 2013). "The evolving role of selective neck dissection for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma". European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 270 (4): 1195–202. doi:10.1007/s00405-012-2153-x. PMID 22903756. S2CID 22423135.

- ↑ Zelefsky MJ, Harrison LB, Fass DE, Armstrong JG, Shah JP, Strong EW (January 1993). "Postoperative radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity and oropharynx: impact of therapy on patients with positive surgical margins". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 25 (1): 17–21. doi:10.1016/0360-3016(93)90139-m. PMID 8416876.

- 1 2 Petrelli F, Coinu A, Riboldi V, Borgonovo K, Ghilardi M, Cabiddu M, et al. (November 2014). "Concomitant platinum-based chemotherapy or cetuximab with radiotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies". Oral Oncology. 50 (11): 1041–8. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.08.005. PMID 25176576.

- 1 2 Chan KK, Glenny AM, Weldon JC, Furness S, Worthington HV, Wakeford H (December 2015). "Interventions for the treatment of oral and oropharyngeal cancers: targeted therapy and immunotherapy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD010341. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010341.pub2. PMID 26625332.

- 1 2 Listl S, Jansen L, Stenzinger A, Freier K, Emrich K, Holleczek B, et al. (GEKID Cancer Survival Working Group) (2013). Scheurer M (ed.). "Survival of patients with oral cavity cancer in Germany". PLOS ONE. 8 (1): e53415. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...853415L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053415. PMC 3548847. PMID 23349710.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ↑ Social inequalities in oral health: from evidence to action (PDF). 2015. p. 9. ISBN 9780952737766. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-12-22. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Cancer of lip, oral cavity and pharynx. [online]". EUCAN. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ↑ "Mouth cancer". www.nhsinform.scot. Archived from the original on 2021-04-23. Retrieved 2021-04-23.

- 1 2 "oral cancer statistics". CancerresearchUK. Archived from the original on 21 September 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ↑ Annertz, Karin; Anderson, Harald; Biörklund, Anders; Möller, Torgil; Kantola, Saara; Mork, Jon; Olsen, Jörgen H.; Wennerberg, Johan (2002-09-01). "Incidence and survival of squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue in Scandinavia, with special reference to young adults". International Journal of Cancer. 101 (1): 95–99. doi:10.1002/ijc.10577. ISSN 0020-7136. PMID 12209594. Archived from the original on 2021-04-24. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ↑ "World Life Expectancy". 2014. Archived from the original on 2021-07-18. Retrieved 2022-03-14.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Diz P, Meleti M, Diniz-Freitas M, Vescovi P, Warnakulasuriya S, Johnson N, Kerr A (2017). "Oral and pharyngeal cancer in Europe". Translational Research in Oral Oncology. 2: 2057178X1770151. doi:10.1177/2057178X17701517.

- ↑ Nemes JA, Redl P, Boda R, Kiss C, Márton IJ, et al. (March 2008). "Oral cancer report from Northeastern Hungary". Pathology Oncology Research. 14 (1): 85–92. doi:10.1007/s12253-008-9021-4. PMID 18351444. S2CID 1187249.

- ↑ Suba Z, Mihályi S, Takács D, Gyulai-Gaál S (2009). "Oral cancer: Morbus hungaricus in the 21st century". Fogorv Sz. 102 (2): 63–68. PMID 19514245.

- ↑ Endre A (2006). "Hungarian national cancer control programme".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Moore SR, Johnson NW, Pierce AM, Wilson DF (March 2000). "The epidemiology of mouth cancer: a review of global incidence". Oral Diseases. 6 (2): 65–74. doi:10.1111/j.1601-0825.2000.tb00104.x. PMID 10702782.

- 1 2 Gupta N, Gupta R, Acharya AK, Patthi B, Goud V, Reddy S, et al. (December 2016). "Changing Trends in oral cancer - a global scenario". Nepal Journal of Epidemiology. 6 (4): 613–619. doi:10.3126/nje.v6i4.17255. PMC 5506386. PMID 28804673.

- 1 2 3 "Cancer Facts & Figures 2017". America cancer society. Archived from the original on 2021-03-18. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ↑ Dalanon J, Esguerra R, Diano LM, Matsuka Y (April 2020). "Analysis of the Filipinos' Interest in Searching Online for Oral Cancer". Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 21 (4): 1121–1127. doi:10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.4.1121. PMC 7445963. PMID 32334480.

- 1 2 Krishna Rao SV, Mejia G, Roberts-Thomson K, Logan R (30 October 2013). "Epidemiology of oral cancer in Asia in the past decade--an update (2000-2012)". Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. Asian Pacific Organization for Cancer Prevention. 14 (10): 5567–77. doi:10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.10.5567. PMID 24289546.

- 1 2 Cheong SC, Vatanasapt P, Yi-Hsin Y, Zain RB, Kerr AR, Johnson NW (2017). "Oral cancer in South East Asia". Translational Research in Oral Oncology. 2: 2057178X1770292. doi:10.1177/2057178X17702921. ISSN 2057-178X.

- ↑ Al-Jaber A, Al-Nasser L, El-Metwally A (March 2016). "Epidemiology of oral cancer in Arab countries". Saudi Medical Journal. 37 (3): 249–55. doi:10.15537/smj.2016.3.11388. PMC 4800887. PMID 26905345.

- 1 2 3 4 "All Cancers (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) Estimated Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012". International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2012. Archived from the original on 2018-09-12. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ↑ Mallath MK, Taylor DG, Badwe RA, Rath GK, Shanta V, Pramesh CS, et al. (May 2014). "The growing burden of cancer in India: epidemiology and social context". The Lancet. Oncology. 15 (6): e205-12. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(14)70115-9. PMID 24731885.

- ↑ Varshitha A (2015). "Prevalence of Oral Cancer in India". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research. 7 (10): e845-48.

- ↑ Chapman DH, Garsa A (2018). "Cancer of the Lip and Oral Cavity". In Hansen E, Roach III M (eds.). Handbook of Evidence-Based Radiation Oncology. Springer International Publishing. pp. 193–207. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-62642-0_8. ISBN 9783319626413.

- ↑ Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Lortet-Tieulent J, Curado MP, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, et al. (December 2013). "Worldwide trends in incidence rates for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 31 (36): 4550–9. doi:10.1200/jco.2013.50.3870. PMC 3865341. PMID 24248688.

- 1 2 3 Farah CS, Simanovic B, Dost F (September 2014). "Oral cancer in Australia 1982-2008: a growing need for opportunistic screening and prevention". Australian Dental Journal. 59 (3): 349–59. doi:10.1111/adj.12198. PMID 24889757.

- ↑ Foale RD, Demetriou J (2010). Saunders Solutions in Veterinary Practice: Small Animal Oncology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-7020-4989-7. Archived from the original on 2021-05-02. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

External links

- A digital manual for the early diagnosis of oral neoplasia (IARC Screening Group) Archived 2015-06-23 at the Wayback Machine

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |