Overjet

| Overjet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overjet or horizontal overlap. | |

| Specialty | Dentistry |

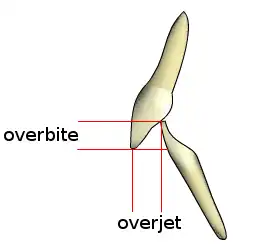

Overjet is the extent of horizontal (anterior-posterior) overlap of the maxillary central incisors over the mandibular central incisors. In class II (division I) malocclusion the overjet is increased as the maxillary central incisors are protruded.

Class II Division I is an incisal classification of malocclusion where the incisal edge of the mandibular incisors lie posterior to the cingulum plateau of the maxillary incisors with normal or proclined maxillary incisors (British Standards Index, 1983). There is always an associated increase in overjet. In the Class II Division 2 incisal classification of malocclusion, the lower incisors occlude posterior to the cingulum plateau of the upper incisors and the upper central incisors are retroclined. The overjet is usually minimal but it may be increased.

Signs and symptoms

Class II Div I

- Benefits associated with orthodontic treatment include a reduction in the susceptibility to caries, periodontal disease and temporomandibular joint dysfunction, whilst also improving speech and masticatory function. However, the supporting evidence is equivocal.[1][2]

- It may be assumed that correction of an increased overjet will potentially reduce the risk of trauma, as it has been shown that individuals with an overjet greater than 3 mm (0.12 in) are twice as likely to suffer injury to their upper incisors.[3]

- Table showing the relationship between size of overjet and prevalence of traumatised anterior teeth[4]

Overjet (mm) Incidence (%) 5 22 9 24 >9 44

- The meta-analysis undertaken in a recent Cochrane review found that 'early orthodontic treatment for children with prominent upper front teeth is more effective in reducing the incidence of incisal trauma than providing one course of orthodontic treatment when the child is in early adolescence'.[5] A number of studies have found that the presence of malocclusion can have a significant impact on an individual’s quality of life and result in reduced self-esteem.[6] Prominent upper incisors may be a target for teasing and bullying and it is now accepted that one reason for undertaking treatment of malocclusion is the psychosocial benefit that it accrues.[7]

Classification of the bad bite

In 1895 Edward Angle, a mid-North American dentist, published a book on the classification of bad bites - a term he latinised and popularised as malocclusion.

The modern discipline of orthodontics was begun by the establishment of the Angle classification of adult first molar relationship. This established that all forms of a bad bite were premised on a natural redundancy of premolar, and in particular third molar teeth (wisdom teeth). Eventually the dual dental specialties of orthodontic and oral surgery were popularised and came to work together in coordinating adolescent dental crowding by the treatment duopoly of extracting excessive teeth, and orthodontically straightening the remaining - especially front - teeth.

Once an assessment is made that there is dental crowding (a bad bite), the Angle classification of malocclusion is based only on an assessment of relative position of the upper and lower first adult molar.

Class I dental crowding is with a normal molar relationship. Class II dental crowding is with a molar relationship where the relative position of the lower molar is behind the Class I position. Class III is with the abnormal molar position being forward of the normal Class I position.

Classifying incisal relationship in the bad bite is made in profile and only of the relative positions upper and lower central incisors.

The terms used relate to visual or radiological (lateral cephalometric) measurements of dental overjet and dental overbite.

Incisal Edge-to-Edge

This describes the incisal relationship where there is both zero overjet and zero overbite, and where the incisal edge of both upper and lower central incisors are in direct edge to edge contact. It is considered a traumatic bite in that it accelerates wear and abnormal acquired incisal form, and unaesthetic smile development.

Incisal Anterior Open Bite

This is where there is no contact between the biting surfaces of the incisor teeth. This prevents both biting and incising. There is a negative incisal overbite, and is independent of overjet measurement.

Incisal Class II Div I

This incisal relationship is usually where there is a long overjet and deep incisal overbite, and is always in company with a Class II first molar relationship.

Instances of long incisal overjet are also associated with Class I or Class III molar relationships.

Incisal Class II Div 2

This incisal relationship is where there is virtually no incisal overjet, and a very deep incisal overbite, and is always associated with a class II molar relationship.

In essence, Class II Div 2 malocclusion is a common description given to extreme crowding, or backward collapse of the anterior teeth and is a common presenting complaint by concerned parents of their child's tooth crookedness.

Class II malocclusion, either with prominent upper incisors (Class II division 1) or exceedingly crowded and collapsed upper incisors (Class II division 2) are the dominant presenting orthodontic malocclusionn types that present to orthodontic offices works wide. They are also the dominant pattern of dental crowding leading to orthodontic premolar extractions, and later impacted wisdom teeth removal by oral surgeons.

Causal propositions for orthodontic malocclusion and incisal crowding states

The Angle classification is merely a means of describing common states or forms or patterns of adolescent dental crowding. These patterns emerge as baby (deciduous) teeth are lost, and a child's face and overall body are growing.

Thus the development of malocclusion and of dental crowding have come to be rationalised as distinct conditions defined by what was originally an arbitrary and simple 19th century classification. As the myth of the veracity of the classification system became entrenched more formally as orthodontic diagnoses, orthodontists attempted to apply epidemiological study as to why these patterns may exist or have become prevalent in modern society.

The overriding premises of the overwhelming majority of these studies are that 1. Malocclusion classifications of dental crowding are in fact diagnostic or disease states, and exist mostly and independently of any other medical condition 2. That malocclusion occurs as a feature or expression of childhood or adolescent growth, and that treatments can be directed at modifying growth and thus improve the abnormal development of malocclusion 3. That dental crowding is due to a redundant number of human teeth, and that this redundancy is due to a modern softer diet compared to a more primitive past, and is more conservatively managed by a combination of dental extractions and orthodontic treatments 4. That being a disease, and that malocclusion and dental crowding is a feature of tooth number redundancy, or oversize of permanent teeth, that epidemiological studies of the natural rates of the various classification states can be made. 5. That there are no other common associated features of malocclusion outside of the dental relationship. Malocclusion exists as a dental disease specific to itself; and that if there are other conditions or anatomical observations, they exist only to aggravate or impact upon the complexity of the malocclusion, or the orthodontic treatment of it.

In orthodontic studies, a number of genetic and environmental factors are postulated to contribute to a Class II division 1 malocclusion:[8]

- Skeletal factors − it is generally agreed that the majority of patients with a Class II malocclusion have some degree of skeletal imbalance with either a retrognathic mandible, protrusive maxilla or, most commonly, a combination

- Dental factors − crowding, spacing, proclined maxillary anterior teeth

- Soft tissue factors − incompetent lips, lower lip trap, tongue thrust

- Habits − digit-sucking, use of pacifiers

Diagnosis

Whenever orthodontic treatment is to be considered, it is essential to carry out a complete patient assessment to get a clear picture of the patient's medical and dental condition before any irreversible treatment (such as extractions) are carried out or the orthodontic treatment causes more harm than benefit. The assessment is also key in establishing the correct diagnosis and likely cause of the malocclusion.

This assessment should include the following:[9]

- Medical History

- Patient's Complaint

- History of Trauma

- Habits

- Extra-Oral Examination

- Intra-Oral Examination

- Radiograph

- Indication of Orthodontic Treatment Need Scoring

- Justification for Treatment

- Treatment Aims

- Treatment Plan

The Extra Oral Examination Should Include:[9]

- Skeletal Pattern

- Anterior-Posterior

- Vertical Dimension

- Transverse

- Soft Tissues

- Temporomandibular Joint Examination

The Intra Oral Examination Should Include:

- Dental health

- Lower arch

- Upper arch

- Teeth in occlusion

- Radiographs

The presence of dental disease precludes any active orthodontic treatment, even if the malocclusion is severe. This is because orthodontic appliances accumulate plaque and combining this with a high carbohydrate diet and poor oral hygiene can result in extensive decalcification of the teeth and accelerated bone loss if you try to move the teeth when there is active gingivitis and periodontal disease.[10]

Overjet is measured from the labial surface of the most prominent incisor to the labial surface of the mandibular incisor. Normally, this measurement is 2–4 mm (0.079–0.157 in). If the lower incisor is anterior to the upper incisors, the overjet is given a negative value.[11] In the UK, an overjet is generally described as increased if it is >3.5 mm (0.14 in). The Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need rates overjet highly on its weighting system, second behind missing teeth. It then grades severity of overjet as:[12]

- Grade 3, Borderline need for treatment = increased overjet 3.5 mm (0.14 in) < 6 mm (0.24 in)

- Grade 4, Need for treatment = increased overjet 6 mm (0.24 in) < 9 mm (0.35 in)

- Grade 5, Need for treatment = increased overjet > 9 mm (0.35 in).

Radiographs can aid your diagnosis. Any radiographs taken must be clinically justified in accordance with the IRMER Regulations 2000.

Radiographs may help by giving you more information on:[11]

- Presence or absence of teeth

- Stage of development of adult dentition

- Root morphology of teeth

- Presence of ectopic or supernumerary teeth

- Presence of dental disease

- Relationship of the teeth to the skeletal dental bases and their relationship to the cranial base.

- Radiographs commonly used in orthodontics assessment include:

- Dental panoramic tomography

- Cephalometric lateral skull radiograph

- Upper standard occlusal radiographs

- Periapical Radiographs

- Bitewing Radiographs

Health complications

Untreated overjet can cause the following health complications:

- Chewing and speaking difficulties.

- Sleep apnoea.

- Jaw pain and headaches, that may contribute to the development of Temporomandibular Joint Disorder (TMD).

- Gum damage (when teeth contact the gum).

- Fractured, worn teeth.

- Chapped lips and dry mouth.[13][14][15]

Treatment

Class II div 1

Early intervention

- Timing of referral for Class II division 1 children is extremely important as late referral may limit the treatment options available, particularly attempts at growth modification. On the other hand, recent evidence strongly suggests that there are few advantages to early treatment (undertaken as a first stage of treatment in the early mixed dentition) for Class II division 1 malocclusion and that starting treatment too early may actually reduce success and long-term outcome. It is therefore now recommended that a single phase of treatment is undertaken once the patient is in the late mixed dentition or early permanent dentition. This is the ideal time for orthodontic referral for the majority of Class II growing patients. The exceptions to this are if there is a significant risk of incisal trauma due to greatly increased overjet, or if the child is being teased or bullied at school. For these patients, early treatment may be indicated and an earlier referral should be made for an orthodontic opinion.[5]

- Any habits must be completely stopped before treatment can be undertaken otherwise treatment is likely to be unsuccessful or relapse after completion.[16]

- Early treatment is defined as treatment provided in the early mixed dentition, usually between the ages of 7−9 years. This has also been called two-phase treatment, whereby a second separate definitive phase of treatment is undertaken when the patient reaches the permanent dentition. Late treatment, or one-phase treatment, is a single course of comprehensive treatment undertaken in the permanent dentition around the age of 12−14 years. Early treatment has been advocated to reduce the risk of incisal trauma, improve psychosocial well-being and reduce bullying.[8]

- It is also been claimed that early treatment can lead to superior outcomes in terms of efficiency, making definitive treatment easier, and efficacy, in that the final result is superior.[17]

- Further assertions have been made for early treatment in terms of improved skeletal pattern, and reduced need for extractions and orthognathic surgery; however, these have been disproved in recent high quality clinical trials. One high-quality randomized controlled trial compared early and late treatment of Class II division 1 malocclusion with functional appliances. Although differences were found between treated patients and untreated controls after the initial phase, following a second phase of treatment there was no lasting difference in terms of skeletal pattern, extraction pattern or self-esteem. Detrimental effects were seen in those who had undergone early treatment; more appointments, longer total treatment time and associated costs, and a worse final occlusal outcome as indicated by the Peer Assessment Rating (PAR).[18]

Functional appliances

- Functional appliances are a range of fixed and removable appliances that cause their effect by influencing the muscle groups that control position and function of the mandible, transmitting forces to the dentition and basal bone.[17] The result is a decrease in overjet and correction of the buccal segment relationship, caused by both skeletal and dental changes. A recent study quantified the changes seen after a first stage of functional treatment. Skeletal change was attributed to restraint of maxillary forward and downward growth and increased growth and forwarding positioning of the mandible, contributing to 27% of the overjet reduction and 41% of buccal segment correction. Dental changes included retroclination of maxillary incisors, proclination of mandibular incisors and mesial eruption of mandibular molars. The majority of overjet reduction and buccal segment correction is dental, 73% and 59%, respectively.[19]

- Soft tissue changes include elimination of lip trap and improved lip competence. It has also been postulated that tongue activity and soft tissue pressures from the lips and cheeks might be altered, enhancing the soft tissue environment.[20]

Twin block appliances

The Twin Block appliance has been used in most studies evaluating functional appliance treatment as it is considered to be the 'gold standard' against which other appliances should be tested. When compared to other functional appliances, the Twin Block appliance was found to produce a statistically significant reduction in skeletal base discrepancy (ANB = -0.68 degrees; 95% CI -1.32 to -0.04) when compared to other functional appliances, although there was no significant effect from the type of appliance on the final overjet.[5] The Twin Block has also been shown to cause clinically significant beneficial changes to the soft tissues.[21]

There are problems associated with the Twin Block including excessive lower incisor proclination, a significant failure-to-complete rate of 25%,[22] and a breakage rate of up to 35%. Lower incisor proclination occurs with most functional appliances and this must be considered during treatment planning and monitored throughout treatment. Twin Block appliances can also cause an increase in vertical dimension, which may be desirable in some cases but may not be beneficial in patients with an increased lower anterior face height. In these patients, careful control of the vertical dimension should be planned.[23]

Herbst appliance

The success rate of the Herbst appliance, often considered to be a 'compliance-free' appliance, was found to be much higher than the Twin Block in one study, with a failure-to-complete rate of 12.9%. This is approximately half that of the Twin Block so may be considered in patients where compliance is predicted to be difficult. However, the Herbst is considerably more expensive and demonstrated a higher breakage rate so that the benefits of reduced compliance requirements must be balanced against this.[24]

Headgear

Headgear exerts force to the dentition and basal bones via extra-oral traction attached directly to bands on the teeth or to a maxillary splint or functional appliance. The effects are mainly dento-alveolar with some skeletal effect through restriction of maxillary downward and forward growth.[25] Several studies found an additional small effect on mandibular growth when headgear is used in conjunction with an anterior bite plane.[26]

The effect of headgear treatment, as early treatment, was compared to one-phase treatment, carried out later, in a study of two trials. Both found a significant reduction in overjet and improvement in skeletal relationship after headgear treatment.[27] There was no difference in any outcomes that could be attributed to treatment timing, with the exception of risk of trauma where the later treatment group showed twice the risk of incisal trauma.[5] The Cochrane review summarizes that 'no significant differences, with respect to final overjet, ANB, or ANB change, were found between the effects of early treatment with headgear and the functional appliances'. However, headgear is highly reliant on good patient compliance, with 12−14 hours a day of wearing required to achieve the effects described.

Fixed appliances

Fixed appliances can be used alone or in combination with extractions or temporary anchorage devices to retract the maxillary teeth to correct a Class II division 1 malocclusion by dental means only. Class II intermaxillary elastics are used to retract the maxillary teeth against the mandibular teeth, with reciprocal mesialization and proclination of the mandibular teeth.

Late intervention

Cochrane review showed that, at the end of all treatment, no significant differences were found in overjet, skeletal relationship or PAR score between the children who had a course of early treatment, with either headgear or functional appliances, and those who had not received early treatment. The only outcome to be affected by treatment timing was the incidence of new incisal trauma, which was significantly reduced by early treatment with either functional appliance or headgear (odds ratio 0.59 and 0.47, respectively). The Cochrane review concludes 'the evidence suggests that providing early orthodontic treatment for children with prominent upper front teeth is more effective in reducing the incidence of incisal trauma than providing one course in early adolescence. There appears to be no other advantage for providing early treatment'.[5]

Epidemiology

Class II Div I

History

Class II div 1

Functional appliances: The first reported use of a mandibular positioning device was the 'Monobloc' by Dr Robin, in France in 1902, for neonates with under-developed mandibles. This was followed by the first functional device for growth modification, the Andresen Activator, in Norway in 1908. A number of German appliances, such as the Herbst appliance in 1934, the Bionator appliance in the 1950s and the Functional Regulator in 1966 followed on. The table below summarizes the various types of functional appliance that are currently in use. The Twin Block, first described by Clark in 1982, consists of two blocks with interlocking 70° bite planes, which cause forward posturing of the mandible.

See also

References

- ↑ Hunt NP. Why should the NHS continue to fund orthodontic treatment in the current financial climate? Royal College of Surgeons of England: Faculty Dental Journal 2013; 4: 16−19. 4.

- ↑ Burden DJ. Oral health-related benefits of orthodontic treatment. Semin Orthod 2007; 13: 76−80.

- ↑ Nguyen QV et al. A systematic review of the relationship between overjet size and traumatic dental injuries. Eur J Orthod 1999; 21: 503−515.

- ↑ Roberts-Harry D & Sandy J. Orthodontics. Part 1: Who needs orthodontics? British Dental Journal 195. 433. (25 October 2003)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Thiruvenkatachari B et al. Orthodontic treatment for prominent upper front teeth (Class II malocclusion) in children. Cochrane Database Syst Revs 2013; 11: CD003452.

- ↑ Rusanen J et al. Quality of life in patients with severe malocclusion before treatment. Eur J Orthod 2010; 32: 43−48.

- ↑ Seehra J, Newton JT, Dibiase AT. Interceptive orthodontic treatment in bullied adolescents and its impact on self-esteem and oral-health-related quality of life. Eur J Orthod 2013; 35(5): 615−621.

- 1 2 Barber, S.K., Forde, K.E. & Spencer, R.J. 2015, "Class II division 1: an evidence-based review of management and treatment timing in the growing patient", Dental Update, vol. 42, no. 7, pp. 632-642.

- 1 2 Roberts-Harry D & Sandy J. 2003. Orthodontics. Part 2: Patient Assessment and Examination I. British Dental Journal 195, 489–493 (08 November 2003)

- ↑ Roberts-Harry D & Sandy J. 2003. Orthodontics. Part 3: Patient assessment and examination II. British Dental Journal 195, 563-565 (22 November 2003).

- 1 2 Mitchell, Laura. 2013. An Introduction to Orthodontics. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ British Orthodontic Society. 2014. Quick Reference Guide to Orthodontic Assessment and Treatment. [Online Guide]. [viewed 7 January 2018] Available from https://www.bos.org.uk

- ↑ Mandal, Ananya (28 June 2019). "What is Orthodontics?".

- ↑ "What's the difference between an overbite and an overjet?". 12 January 2020.

- ↑ "Malocclusion - difference between overbite, overjet and open bite". 2 June 2017.

- ↑ Proffit WR, Fields HW, Sarver DM, eds. Contemporary Orthodontics 5th edn. Oxford: Elsevier Mosby, 2013.

- 1 2 Proffit WR, Tulloch JF. Preadolescent Class II problems: treat now or wait? Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2002; 121: 560−562

- ↑ O’Brien K et al. Early treatment for Class II Division 1 malocclusion with the Twin-block appliance: a multi-center, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2009; 135: 573−579.

- ↑ O’Brien K et al. Effectiveness of early orthodontic treatment with the Twin-block appliance: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Part 1: Dental and skeletal effects. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003; 124: 234−243; quiz 339.

- ↑ McDowall RJ, Waring DT. Class II growth modification: evidence of absence or absence of evidence. Orthod Update 2010; 3: 44−50.

- ↑ Morris DO, Illing HM, Lee RT. A prospective evaluation of Bass, Bionator and Twin Block appliances. Part II − The soft tissues. Eur J Orthod 1998; 20: 663−684.

- ↑ O’Brien K et al. Effectiveness of treatment for Class II malocclusion with the Herbst or twin-block appliances: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003; 124: 128−137

- ↑ Lee RT, Kyi CS, Mack GJ. A controlled clinical trial of the effects of the Twin Block and Dynamax appliances on the hard and soft tissues. Eur J Orthod 2007; 29: 272−282.

- ↑ O’Brien K et al. Effectiveness of treatment for Class II malocclusion with the Herbst or twin-block appliances: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003; 124: 128−137.

- ↑ Ghafari J et al. Headgear versus function regulator in the early treatment of Class II, division 1 malocclusion: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998; 113: 51−61.

- ↑ Keeling SD et al. Anteroposterior skeletal and dental changes after early Class II treatment with bionators and headgear. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998; 113: 40−50.

- ↑ Tulloch JF, Proffit WR, Phillips C. Outcomes in a 2-phase randomized clinical trial of early Class II treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2004; 125: 657−667.

- ↑ Todd JE, Dodd T. Children’s Dental Health in the United Kingdom. London: HMSO, 1985.