Physical restraint

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

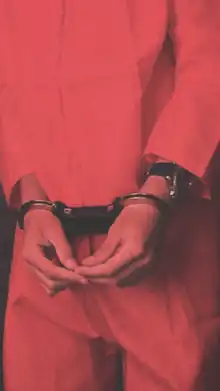

Physical restraint refers to means of purposely limiting or obstructing the freedom of a person's bodily movement.

Basic methods

Usually, binding objects such as handcuffs, legcuffs, ropes, chains, straps or straitjackets are used for this purpose. Alternatively different kinds of arm locks deriving from unarmed combat methods or martial arts are frequently used to restrain a person, which are predominantly used by trained police or correctional officers. This less commonly also extends to joint locks and pinning techniques.

The freedom of movement in terms of locomotion is usually limited, by locking a person into an enclosed space, such as a prison cell and by chaining or binding someone to a heavy or immobile object. This effect can also be achieved by seizing and withholding specific items of clothing, that are normally used for protection against common adversities of the environment. Examples can be protective clothing against temperature, forcing the individual to remain in a sheltered spot. A practice employed in countries including Zimbabwe[1] is to take away a prisoner's shoes, forcing them to remain barefoot. The freedom of movement is practically restricted in many everyday situations without the protection offered by conventional footwear. Controlling the free movement of detainees by keeping them barefoot is therefore common practice in many countries.

British police use

British Police officers are authorised to use leg and arm restraints, if they have been instructed in their use. Guidelines set out by the Association of Chief Police Officers dictate that restraints are only to be used on subjects who are violent while being transported, restraining the use of their arms and legs, minimising the risk of punching and kicking. Pouches carrying restraints are usually carried on the duty belt, and in some cases carried in police vans.

Purpose

Physical restraints are used:

- primarily by police and prison authorities to obstruct delinquents and prisoners from escaping or resisting[2]

- to enforce corporal punishment (typically a form of flagellation) by impeding motions of the target (usually prisoner), as is still practiced in penal functions of several countries

- by specially-trained teachers or teaching assistants to restrain children and teenagers with severe behavioral problems or disorders like autism or Tourette syndrome, to prevent hurting others or themselves

- approximately 70% of teachers who work with students with behavioral disabilities use a type of physical restraint (Goldstein & Brooks, 2007)

- often used in emergency situations or for de-escalation purposes (Ryan & Peterson, 2004)

- many educators believe restraints are used to maintain the safety and order of the classroom and students, while those who oppose their use believe they are dangerous to the physical and mental health of children and may result in death (McAfee, Schwilk & Miltruski, 2006) and (Kutz, 2009).

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act has stated that "Restraints may not be used as an alternative to adequate staff" (McAfee, Schwilk & Miltruski, 2006, p. 713). Also, "restraint may be used only when aggressive behavior interferes with an individual's own ability to benefit from programming or poses physical threat to others" (McAfee, Schwilk & Miltruski, 2006, p. 713).

- by escapologists, illusionists and stunt performers

- to restrain people who are suffering from involuntary physical spasms, to prevent them from hurting themselves (see medical restraints)

- controversially, in psychiatric hospitals

- restraints were developed during the 1700s by Philippe Pinel and performed with his assistant, Jean-Baptiste Pussin in hospitals in France

- by a kidnapper (stereotypically with rope or duct tape and a gag) or other material

- for eroticism

Misuse and risks of physical restraints

Restraining someone against their will is generally a crime in most jurisdictions, unless it is explicitly sanctioned by law. (See false arrest, false imprisonment).

The misuse of physical restraint has resulted in many deaths. Physical restraint can be dangerous, sometimes in unexpected ways. Examples include:

- postural asphyxia

- unintended strangulation

- death due to choking or vomiting and being unable to clear the airway

- death due to inability to escape in the event of fire or other disaster

- death due to dehydration or starvation due to the inability to escape

- cutting off of blood circulation by restraints

- nerve damage by restraints

- cutting of blood vessels by struggling against restraints, resulting in death by loss of blood

- death by hypothermia or hyperthermia whilst unable to escape

- death from deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism due to lack of movement

For these and many other reasons, extreme caution is needed in the use of physical restraint.

Gagging a restrained person is highly risky, as it involves a substantial risk of asphyxia, both from the gag itself, and also from choking or vomiting and being unable to clear the airway. In practice, simple gags do not restrict communication much; however, this means that gags that are effective enough to prevent communication are generally also potentially effective at restricting breathing. Gags that prevent communication may also prevent the communication of distress that might otherwise prevent injury.

Medical restraints

A survey in the US in 1998 reported an estimated 150 restraint related deaths in care environments (Weiss, 1998). Low frequency fatalities occur with some degree of regularity.[3] An investigation of 45 restraint related deaths in US childcare settings showed 28 of these deaths were reported to have occurred in the prone position.[3] In the UK restraint related deaths would appear to be reported less often. The evidence for effective staff training in the use of medical restraints is at best crude,[4] with evaluation of training programmes being the exception rather than the rule.[5] Vast numbers of care staff are trained in 'physical interventions' including physical restraint, although they rarely employ them in practice. It is accepted that staff training in physical interventions can increase carer confidence.[6]

Japan

Japanese law states that psychiatric hospitals may use restraints on patients only if there is a danger that the patients will harm themselves. The law also states that a designated psychiatrist must approve the use of restraints and examine the patient at least every 12 hours to determine whether the situation has changed and the patient should be removed from restraints.[7] However, in practice, Japanese psychiatric hospitals use restraints fairly often and for long periods. Despite being required to certify every 12 hours whether a patient still needs restraints, Japanese psychiatric hospitals keep patients in restraints for a much longer time than hospitals in other countries. According to a survey conducted on 689 patients in 11 psychiatric hospitals in Japan, the average time spent in physical restraints is 96 days.[8] Meanwhile, the average time in most other developed countries is at most several hours to tens of hours.

The number of people who are physically restrained in Japanese psychiatric hospitals continues to increase. In 2014 more than 10,000 people were restrained-the highest ever recorded, and more than double the number a decade earlier.[9] It is thought that some of that increase includes older patients with dementia. As a result, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has revised its guidelines for elderly people in nursing homes to have more restrictions against body restraints. The changes will take effect on 1 April 2018.[10]

United Kingdom

The Millfields Charter is an electronic charter which promotes an end to the teaching to frontline healthcare staff of all prone (face down) restraint holds.[15] In June 2013 the UK government announced that it was considering a ban on the use of face-down restraint in English mental health hospitals.[16]

Face down restraints are used more often on women and girls than on men. 51 out of 58 mental health trusts use restraints unnecessarily when other techniques would work. Organisations opposed to restraints include Mind and Rethink Mental Illness. YoungMinds and Agenda claim restraints are "frightening and humiliating" and "re-traumatises" patients especially women and girls who have previously been victims of physical and/or sexual abuse. The charities sent an open letter to health secretary, Jeremy Hunt showing evidence from 'Agenda, the alliance for women and girls at risk', revealing that patients are routinely restrained in some mental health units while others use non-physical ways to calm patients or stop self-harm. According to the letter over half of women with psychiatric problems have suffered abuse, restraint can cause physical harm, can frighten and humiliate the victim. Restraint, specially face down restraint can re-traumatise patients who previously suffered violence and abuse. "Mental health units are meant to be caring, therapeutic environments, for people feeling at their most vulnerable, not places where physical force is routine".

Government guidelines state that face down restraint should not be used at all and other types of physical restraint are only for last resort. Research by Agenda found one fifth of women and girl patients in mental health units had suffered physical restraint. Some trusts averaged over twelve face down restraints per female patient. Over 6% of women, close to 2,000 were restrained face-down in total more than 4,000 times. The figures vary widely between regions.

Some trusts hardly use restraints, others use them routinely. A woman patient was in several hospitals and units at times for a decade with mental health issues, she said in some units she suffered restraints two or three times daily. Katharine Sacks-Jones director of Agenda, maintains trusts use restraint when alternatives would work. Sacks-Jones maintains women her group speak to repeatedly describe face down restraint as a traumatic experience. On occasions male nurses have used it when a woman did not want her medication. "If you are a woman who has been sexually or physically abused, and mental health problems in women often have close links to violence and abuse, then a safer environment has to be just that: safe and not a re-traumatising experience. (...) Face-down restraint hurts, it is dangerous, and there are some big questions around why it is used more on women than men".[17] The use of restraints in UK psychiatric facilities is increasing.[18]

See also

- Badge of shame

- Barefoot

- Corporal punishment

- Detention

- Flagellation

- Handcuffs

- Judicial corporal punishment

- Legcuffs

- Pain compliance

- Pin-down scandal

- Prison

- Prison uniform

- Prisoner

- Prisoner abuse

- Public humiliation

- Restraint chair

- Rope

- Strap

- Strapping (punishment)

References

- ↑ "Zimbabwe's jails: full of human kindness?". GlobalPost.

- ↑ Kelley, Debbie (2 March 2017). ""Culture of violence" in Colorado Youth Corrections includes physical restraints, solitary". The Gazette.

- 1 2 Nunno, Michael A.; Holden, Martha J.; Tollar, Amanda (December 2006). "Learning from tragedy: A survey of child and adolescent restraint fatalities". Child Abuse & Neglect. 30 (12): 1333–1342. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.02.015. PMID 17109958.

- ↑ Allen, D. (2000b). Training carers in physical interventions: Research towards evidence based practice. Kidderminster: British Institute of learning Disabilities.

- ↑ Beech, B & Leather, P. (2006). Workplace violence in the healthcare sector: A review of staff training and integration of training models. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 11, 27-43.

- ↑ Cullen, C. (1992). Staff training and management for intellectual disability services. International Review of Research in Mental Retardation. 18, 225-245.

- ↑ "Number of patients physically restrained at psychiatric hospitals soars". The Japan Times Online. 9 May 2016.

- ↑ 長谷川利夫. (2016). 精神科医療における隔離・ 身体拘束実態調査 ~その急増の背景要因を探り縮減への道筋を考える~. 病院・地域精神医学, 59(1), 18–21.

- ↑ "身体拘束と隔離がまた増えた" (in Japanese). Yomiuri Online.

- ↑ "介護施設、拘束の要件厳格化" [Tough changes in requirements for physical restraints in nursing homes] (in Japanese). Reuters Japan. 4 December 2017.

- ↑ Otake, Tomoko (18 July 2017). "Family blames prolonged use of restraints at Kanagawa hospital for English teacher's death". The Japan Times Online.

- ↑ "日本の 精神科医療を 考える シンポジウム". norestraint.org (in Japanese).

- ↑ "Kiwi mum's fight to end restraints in Japan's psychiatric hospitals". Radio New Zealand. 14 May 2018.

- ↑ "施設「頭打ちそうで拘束」 入所の障害者男性死亡 青梅". Asahi Shimbun.

- ↑ "Millfields Charter - against abusive practice". millsfieldcharter.com.

- ↑ "'Excessive' use of face-down restraint in mental health hospitals". bbc.co.uk. 18 June 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ↑ McVeigh, Tracy (4 March 2017). "End humiliating restraint of mentally ill people, say charities". The Guardian.

- ↑ Greenwood, George (16 November 2017). "Rise in mental health patient restraints". BBC News.

Sources

- Goldstein & Brooks, S., R.B (2007). Understanding and managing children's classroom behavior: Creating sustainable, resilient classrooms. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- McAfee, Schwilk, & Mitruski, J., C., & M. (2006). Public policy on physical restraint of children with disabilities in public schools. Education and Treatment of Children.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ryan & Peterson, J. & R. (2004). Physical restraint in school. Behavioral Disorders.

- Kutz, Gregory. "Selected Cases of Death and Abuse at Public and Private Schools and Treatment Centers" (PDF). Testimony Before the Committee on Education and Labor, House of Representatives, United States Government Accountability Office. United States Government Accountability Office.