Posthumous sperm retrieval

Posthumous sperm retrieval (PSR) is a procedure in which spermatozoa are collected from the testes of a human corpse after brain death. There has been significant debate over the ethics and legality of the procedure, and on the legal rights of the child and surviving parent if the gametes are used for impregnation.[1]

Cases of post-mortem conception have occurred ever since human artificial insemination techniques were first developed, with sperm donated to a sperm bank being used following the death of the donor. While religious arguments have been brought against the process even under these circumstances, far more censure has arisen from a number of quarters with regards to invasive retrieval from fresh cadavers or patients either on life support or in a persistent vegetative state, particularly when the procedure is carried out without explicit consent from the donor.

Cases

The first successful retrieval of sperm from a cadaver was reported in 1980, in a case involving a 30-year-old man who became brain dead following a motor vehicle accident and whose family requested sperm preservation.[2] The first successful conception using sperm retrieved post-mortem was reported in 1998, leading to a successful birth the following year.[3] Since 1980, a number of requests for the procedure have been made, with around one third approved and performed.[1] Gametes have been extracted through a variety of means, including removal of the epididymis, irrigation or aspiration of the vas deferens, and rectal probe electroejaculation.[3] Since the procedure is rarely performed, studies on the efficacy of the various methods have been fairly limited in scope.

While medical literature recommends that extraction take place no later than 24 hours after death, motile sperm has been successfully obtained as late as 36 hours after death, generally regardless of the cause of death or method of extraction. Up to this limit, the procedure has a high success rate, with sperm retrieved in nearly 100% of cases, and motile sperm in 80–90%.[4] There is currently little precedent for successful insemination using sperm harvested after 36 hours. New technologies are being researched that could make this a routine reality, in turn creating new ethical dilemmas.[5]

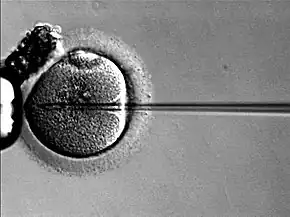

If the sperm is viable, fertilisation is generally achieved through intracytoplasmic sperm injection, a form of in vitro fertilisation. The success rate of in vitro fertilisation remains unchanged regardless of whether the sperm was retrieved from a living or dead donor.[4]

Legality

The legality of posthumous sperm extraction varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Generally, legislation falls into one of three camps: a full ban, a requirement of written consent from the donor, or implied consent obtained from the family.

Areas with full bans

Following the 1984 Parpalaix case in France, in which the widow of deceased cancer patient Alain Parpalaix obtained permission from the courts to be inseminated with her husband's spermatozoa after his death, the Centre d’Etude et de Conservation du Sperme Humain (Center for the Study and Preservation of Human Sperm) petitioned the courts successfully for a full ban on posthumous insemination,[6] in line with the country's ban on in vitro fertilisation for post-menopausal women.[7]

Similar legislation exists in Germany, Sweden, and the Australian states of Victoria, Western Australia[6] and Taiwan.

Areas requiring written consent

Guidelines outlining the legal use of posthumously extracted gametes in the United Kingdom were laid out in the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990. The Act dictates that explicit written consent by the donor must be provided to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority in order for extraction and fertilisation to take place.[8] Following the 1997 case of Regina v. Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, the terms of the Act were extended to comatose patients, and so theoretically assault charges could be (but in this case were not) brought against doctors for overseeing or performing the procedure.[6]

There are few other jurisdictions that fall into this category. New York senator Roy M. Goodman proposed a bill in 1997 requiring written consent by the donor in 1998, but it was never passed into law.[9]

Areas requiring implied consent

In 2003, Israeli Attorney General Elyakim Rubinstein published several guidelines outlining the legal situation of posthumous sperm retrieval for the purpose of later insemination by a surviving female partner. The guidelines specified firstly that only requests by a partner (married or otherwise) of the deceased would be honoured – requests by other members of the donor's family would be denied. While extraction of the sperm was guaranteed following a request by the partner, permission to use the sperm was to be determined case by case, a court of law deciding on the basis of the effect on the presumed wishes of the donor, and the effect of the procedure on the donor's dignity. If it could be demonstrated that the deceased took definite steps towards parenthood (implied consent), use of extracted sperm by the female partner would generally be permitted.[10]

No legislation

Many other countries, including Belgium and the United States,[6] have no specific legislation regarding the rights of men on gamete donation following their death, leaving the decision in the hands of individual clinics and hospitals. As such, many medical institutions in such countries institute in-house policies regarding circumstances in which the procedure would be performed.[11]

Ethics

There are several ethical issues surrounding the extraction and use of gametes from cadavers or patients in a persistent vegetative state. The most debated are those concerning religion, consent, and the rights of the surviving partner and child if the procedure results in a birth.

A number of major religions view posthumous sperm retrieval in a negative light, including Roman Catholicism[12] and Judaism.[13] Roman Catholicism proscribes the procedure on much the same grounds as in vitro fertilisation, namely the rights of the unborn. Judaic strictures are based on the halakhic prohibition on deriving personal benefit from a corpse, and in the case of those in a persistent vegetative state, their categorisation as gosses (dying person) prohibits anyone from touching or moving them for anything that does not relate to their immediate care.[13]

Consent of the donor is a further ethical barrier. Even in jurisdictions where implicit consent is not required, there are occasions in which clinicians have refused to perform the procedure on these grounds.[11] If no proof of consent by the donor can be produced, implied consent, often in the form of prior actions, must be evident for clinicians to proceed with the extraction. Sperm retrieval is rarely carried out if there is evidence that the deceased clearly objected to the procedure prior to his death.

Finally, if the procedure is performed and results in a birth, there are several issues involving the legal rights of the child and its mother. Because posthumous insemination can take place months or even years after the father's death, it can in some cases be difficult to prove the paternity of the child. As such, inheritance and even the legal rights of the child to marry (due to the possibility of consanguinity between partners) can be affected. For this reason, several countries, including Israel and the United Kingdom, impose a maximum term for the use of extracted sperm, after which the father will not be legally recognised on the child's birth certificate.[6][10]

See also

- Posthumous birth

- Sperm theft

References

- 1 2 Orr, RD; Siegler, M (2002) Is posthumous semen retrieval ethically permissible? J Med Ethics 2002;28:299–302

- ↑ Rothman, CM (1980) "A method for obtaining viable sperm in the postmortem state." Fertil. Steril. 1980;34(5):512.

- 1 2 Strong, C; Gingrich, JR; Kutteh, WH (2000), "Ethics of sperm retrieval after death or persistent vegetative state," Human Reproduction 2000;15(4):739–745

- 1 2 Shefi S et al. (2006) "Posthumous sperm retrieval: Analysis of time interval to harvest sperm", Human Reproduction 2006;21(11):2890–2893

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-05-05. Retrieved 2013-05-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Bahadur, G (2002) "Death and conception", Human Reproduction Oct 2002;17(10):2769–2775

- ↑ "62-year-old woman gives birth" Archived 2007-08-10 at the Wayback Machine, CNN, May 30, 2001. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- ↑ Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990 (c. 37), specifically Schedule 3, Paragraph 5

- ↑ "Life after death – New York state moves to keep dead men's sperm in the family"; Cohen, Philip; New Scientist (21 March 1998. Retrieved 28 June 2007)

- 1 2 Landau, R (2004) "Posthumous sperm retrieval for the purpose of later insemination or IVF in Israel: an ethical and psychosocial critique", Human Reproduction 2004 19(9):1952–1956

- 1 2 See guidelines Archived 2007-08-16 at the Wayback Machine provided by Cornell University to various New York hospitals for an example.

- ↑ Instruction on respect for human life in its origin and on the dignity of procreation, Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, February 22, 1987. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- 1 2 Grazi, R V; Wolowelsky J B. (1995) "The Use of Cryopreserved Sperm and Pre-embryos In Contemporary Jewish Law and Ethics", Assisted Reproductive Technology-Andrology, 8:53–61