Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

| Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy | |

|---|---|

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy | |

| Other names | PEG tube |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Complications | Infection, Hemorrhage, Gastrointestinal perforation, Gastrocolic fistula, Buried bumper syndrome |

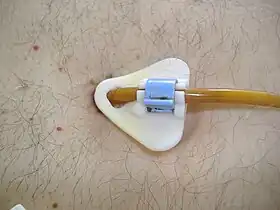

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is an endoscopic medical procedure in which a tube (PEG tube) is passed into a patient's stomach through the abdominal wall, most commonly to provide a means of feeding when oral intake is not adequate (for example, because of dysphagia or sedation). This provides enteral nutrition (making use of the natural digestion process of the gastrointestinal tract) despite bypassing the mouth; enteral nutrition is generally preferable to parenteral nutrition (which is only used when the GI tract must be avoided). The PEG procedure is an alternative to open surgical gastrostomy insertion, and does not require a general anesthetic; mild sedation is typically used. PEG tubes may also be extended into the small intestine by passing a jejunal extension tube (PEG-J tube) through the PEG tube and into the jejunum via the pylorus.[1]

PEG administration of enteral feeds is the most commonly used method of nutritional support for patients in the community. Many stroke patients, for example, are at risk of aspiration pneumonia due to poor control over the swallowing muscles; some will benefit from a PEG performed to maintain nutrition. PEGs may also be inserted to decompress the stomach in cases of gastric volvulus.[2]

Indications

Gastrostomy may be indicated in numerous situations, usually those in which normal (or nasogastric) feeding is impossible. The causes for these situations may be neurological (e.g. stroke), anatomical (e.g. cleft lip and palate during the process of correction) or other (e.g. radiation therapy for tumors in head & neck region).

In certain situations where normal or nasogastric feeding is not possible, gastrostomy may be of no clinical benefit. In advanced dementia, studies show that PEG placement does not in fact prolong life.[3] Instead, oral assisted feedings are preferable.[4] Quality improvement protocols have been developed with the aim of reducing the number of non-beneficial gastrostomies in patients with dementia.[5]

A gastrostomy can be placed to decompress the stomach contents in a patient with a malignant bowel obstruction. This is referred to as a "venting PEG" and is placed to prevent and manage nausea and vomiting.

A gastrostomy can also be used to treat volvulus of the stomach, where the stomach twists along one of its axes. The tube (or multiple tubes) is used for gastropexy, or adhering the stomach to the abdominal wall, preventing twisting of the stomach.[2]

A PEG tube can be used in providing gastric or post-surgical drainage.[6]

Techniques

Two major techniques for placing PEGs have been described in the literature.

The Gauderer-Ponsky technique involves performing a gastroscopy to evaluate the anatomy of the stomach. The anterior stomach wall is identified and techniques are used to ensure that there is no organ between the wall and the skin:

- digital pressure is applied to the abdominal wall, which can be seen indenting the anterior gastric wall by the endoscopist.

- transillumination (diaphanoscopy): the light emitted from the endoscope within the stomach can be seen through the abdominal wall.

- a small (21G, 40mm) needle is passed into the stomach before the larger cannula is passed.

An angiocath is used to puncture the abdominal wall through a small incision, and a soft guidewire is inserted through this and pulled out of the mouth. The feeding tube is attached to the guidewire and pulled through the mouth, esophagus, stomach, and out of the incision.[2]

In the Russell introducer technique, the Seldinger technique is used to place a wire into the stomach, and a series of dilators are used to increase the size of the gastrostomy. The tube is then pushed in over the wire.[7]

Anesthetic management

There are several techniques such as; moderate sedation with left transversus abdominis plane block, and moderate sedation with local anesthetic infiltration at feeding tube site. [8]

Contraindications

As with other types of feeding tubes, care must be made to place PEGs into an appropriate population. The following are contraindications to PEG use:[9]

Absolute contraindications

- Inability to perform an esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- Uncorrected coagulopathy

- Peritonitis

- Untreatable (loculated) massive ascites

- Bowel obstruction (unless the PEG is sited to provide drainage)

Relative contraindications

- Massive ascites

- Gastric mucosal abnormalities: large gastric varices, portal hypertensive gastropathy

- Previous abdominal surgery, including previous partial gastrectomy: increased risk of organs interposed between gastric wall and abdominal wall

- Morbid obesity: difficulties in locating stomach position by digital indentation of stomach and transillumination

- Gastric wall neoplasm

- Abdominal wall infection: increased risk of infection of PEG site

- Intra-abdominal malignancy with peritoneal involvement (tumor seeding into formed channel with subsequent failure)

In advanced dementia

The American Medical Directors Association, the American Geriatrics Society and the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine recommend against inserting percutaneous feeding tubes in individuals with advanced dementia and, instead, recommend oral assisted feedings. Artificial nutrition neither prolongs life nor improves its quality in patients with advanced dementia. It may increase the risk of the patient inhaling food, it does not reduce suffering, it may cause fluid overload, diarrhea, abdominal pain and local complications, and can reduce the amount of human interaction the patient experiences.[10]

Complications

- Surgical site infection around the gastrostomy site. Administration of intravenous antibiotics can reduce infection around the gastrostomy site.[11] Prophylaxis with co-amoxiclav decreases the proportion of people developing MRSA infections compared with no antibiotic prophylaxis (in people without cancer) undergoing percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy insertion.[12]

- Hemorrhage

- Gastric ulcer either at the site of the button or on the opposite wall of the stomach ("kissing ulcer")

- Perforation of bowel (most commonly transverse colon) leading to peritonitis

- Puncture of the left lobe of the liver leading to liver capsule pain

- Gastrocolic fistula: this may be suspected if diarrhea appears a short time after feeding. In this case, the feed goes direct from stomach to colon (usually transverse colon)[13]

- Gastric separation

- "Buried bumper syndrome" (the gastric part of the tube migrates into the gastric wall)[14]

Removal of PEG tubes

Indications

- PEG tube no longer required (recovery of swallow after stroke or brain trauma, or after surgery or radiotherapy for head and neck cancer)

- Persistent infection of PEG site

- Failure, breakage or deterioration of PEG tube (a new tube can be sited along the existing track)

- "Buried bumper syndrome"

Techniques

PEG tubes with rigid, fixed "bumpers" are removed endoscopically. The PEG tube is pushed into the stomach so that part of the tube is visible behind the bumper. An endoscopy snare is then passed through the endoscope, and passed over the bumper so that the tube adjacent to the bumper is grasped. The external part of the tube is then cut, and the tube is withdrawn into the stomach, and then pulled up into the esophagus and removed through the mouth. The PEG site heals without intervention.

PEG tubes with a collapsible or deflatable bumper can be removed using traction (simply by pulling the PEG tube out through the abdominal wall).

History

The first percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy performed on a child was on June 12, 1979, at the Rainbow Babies & Children's Hospital, University Hospitals of Cleveland. Dr. Michael W.L. Gauderer, pediatric surgeon, Dr. Jeffrey Ponsky, endoscopist, and Dr. James Bekeny, surgical resident, performed the procedure on a 4+1⁄2-month-old child with inadequate oral intake.[15] The authors of the technique, Dr. Michael W.L. Gauderer and Dr. Jeffrey Ponsky, first published the technique in 1980.[15] In 2001, the details of the development of the procedure were published, the first author being the originator of the technique itself.[2]

See also

References

- ↑ "Discussion". BCM Gastroenterology Grand Rounds. Baylor College of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2012-03-03. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- 1 2 3 4 Gauderer MW (2001). "Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy-20 years later: a historical perspective". J. Pediatr. Surg. 36 (1): 217–9. doi:10.1053/jpsu.2001.20058. PMID 11150469.

- ↑ Murphy LM, Lipman TO (2003). "Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy does not prolong survival in patients with dementia". Arch. Intern. Med. 163 (11): 1351–3. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.610.6648. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.11.1351. PMID 12796072.

- ↑ AMDA – The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine (February 2014), "Ten Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, AMDA – The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine, retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ↑ Monteleoni C, Clark E (2004). "Using rapid-cycle quality improvement methodology to reduce feeding tubes in patients with advanced dementia: before and after study". BMJ. 329 (7464): 491–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7464.491. PMC 515202. PMID 15331474.

- ↑ Gail Waldby, "PEG-J Gastrostomy drainage jejunal feeding tubes" "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Deitel M, Bendago M, Spratt EH, Burul CJ, To TB (1988). "Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy by the "pull" and "introducer" methods". Can J Surg. 31 (2): 102–4. PMID 3349370.

- ↑ Abdalgaleil, Mohamed M; Shaat, Ahmed M; Elbalky, Osama S; Elnagaar, Mohamed S; Kamoun, Amr M (2018-07-01). "Early versus delayed feeding after placement of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube with safe anesthetic techniques". Menoufia Medical Journal. Medknow Publications. 31 (3): 1058–1063.

- ↑ Gastroenterological endoscopy. Meinhard Classen, G. N. J. Tytgat, Charles J. Lightdale. 2002. ISBN 978-1-58890-013-5

- ↑ Lay summary: "Feeding tubes for people with Alzheimer's disease: When you need them — and when you don't" (PDF). Consumer Reports. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- "White Paper on Surrogate Decision-Making and Advance Care Planning in Long-Term Care". American Medical Directors Association -. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- Daniel K, Rhodes R, Vitale C, Shega J (May 2013). "Feeding Tubes in Advanced Dementia Position Statement" (PDF). American Geriatrics Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- Buff DD (Spring 2006). "Against the Flow: Tube Feeding and Survival in Patients with Dementia" (PDF). AAHPM Bulletin. American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 7 (1). Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ↑ Lipp A, Lusardi G, et al. (The Cochrane Collaboration) (November 2013). Lipp A (ed.). "Systemic antimicrobial prophylaxis for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (11): CD005571. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005571.pub3. PMC 6823215. PMID 24234575.

- ↑ Gurusamy KS, Koti R, Wilson P, Davidson BR, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (August 2013). "Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) related complications in surgical patients". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD010268. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010268.pub2. PMID 23959704.

- ↑ Siamak Milanchi and Matthew T Wilson (January–March 2008). "Malposition of percutaneous endoscopic-guided gastrostomy: Guideline and management". J Minim Access Surg. 4 (1): 1–4. doi:10.4103/0972-9941.40989. PMC 2699054. PMID 19547728.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ Walters G, Ramesh P, Memon MI (2005). "Buried Bumper Syndrome complicated by intra-abdominal sepsis". Age and Ageing. 34 (6): 650–1. doi:10.1093/ageing/afi204. PMID 16267197.

- 1 2 Gauderer MW, Ponsky JL, Izant RJ (1980). "Gastrostomy without laparotomy: a percutaneous endoscopic technique". J. Pediatr. Surg. 15 (6): 872–5. doi:10.1016/S0022-3468(80)80296-X. PMID 6780678.