Gastric varices

| Gastric varices | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Gastroenterology Hematology |

| Symptoms | vomiting blood passing black stool |

| Complications | Internal bleeding, hypovolemic shock, cardiac arrest |

Gastric varices are dilated submucosal veins in the lining of the stomach, which can be a life-threatening cause of bleeding in the upper gastrointestinal tract. They are most commonly found in patients with portal hypertension, or elevated pressure in the portal vein system, which may be a complication of cirrhosis. Gastric varices may also be found in patients with thrombosis of the splenic vein, into which the short gastric veins that drain the fundus of the stomach flow. The latter may be a complication of acute pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, or other abdominal tumours, as well as hepatitis C. Gastric varices and associated bleeding are a potential complication of schistosomiasis resulting from portal hypertension.

Patients with bleeding gastric varices can present with bloody vomiting (hematemesis), dark, tarry stools (melena), or rectal bleeding. The bleeding may be brisk, and patients may soon develop shock. Treatment of gastric varices can include injection of the varices with cyanoacrylate glue, or a radiological procedure to decrease the pressure in the portal vein, termed transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt or TIPS. Treatment with intravenous octreotide is also useful to shunt blood flow away from the stomach's circulation. More aggressive treatment, including splenectomy (surgical removal of the spleen) or liver transplantation, may be required in some cases.

Signs and symptoms

Gastric varices can present in two major ways. First, patients with cirrhosis may be enrolled in screening gastroscopy programs to detect esophageal varices. These evaluations may detect gastric varices that are asymptomatic. When gastric varices are symptomatic, however, they usually present acutely and dramatically with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The symptoms can include vomiting blood, melena (passing black, tarry stools); or passing maroon stools or frank blood in the stools. Many people with bleeding gastric varices present in shock due to the profound loss of blood.[1]

Secondly, patients with acute pancreatitis may present with gastric varices as a complication of a blood clot in the splenic vein. The splenic vein sits over the pancreas anatomically, and inflammation or cancers of the pancreas may result in a blood clot forming in the splenic vein. As the short gastric veins of the fundus of the stomach drain into the splenic vein, thrombosis of the splenic vein will result in increased pressure and engorgement of the short veins, leading to varices in the fundus of the stomach.

Laboratory testing usually shows low red blood cell count and often a low platelet count. If cirrhosis is present, there may be coagulopathy manifested by a prolonged INR; both of these may worsen the bleeding from gastric varices.[2]

In very rare cases, gastric varices are caused by splenic vein occlusion as a result of the mass effect of slow-growing pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors.

Diagnosis

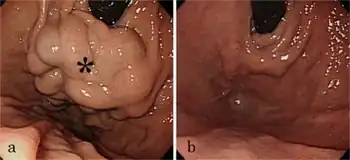

Diagnosis of gastric varices is often made at the time of upper endoscopy.[3]

Classification

The Sarin classification of gastric varices identifies four different anatomical types of gastric varices, which differ in terms of treatment modalities.[4]

Treatment

Initial treatment of bleeding from gastric varices focuses on resuscitation, much as with esophageal varices. This includes administration of fluids, blood products, and antibiotics.[5][6]

Another treatment for gastric varices is injection of the varices with cyanoacrylate, first described by German surgeon Nib Soehendra and colleagues in 1986.[7] The results from two randomized trials comparing band ligation vs cyanoacrylate suggests that endoscopic injection of cyanoacrylate, known as gastric variceal obliteration or GVO is superior to band ligation in preventing rebleeding rates. Cyanoacrylate, a common component in 'super glue' is often mixed 1:1 with lipiodol to prevent polymerization in the endoscopy delivery optics, and to show on radiographic imaging. GVO is usually performed in specialized therapeutic endoscopy centers. Complications include sepsis, embolization of glue, and obstruction from polymerization in the lumen of the stomach.

Other techniques for refractory bleeding include:[8]

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS)

- Balloon occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration techniques (BORTO)

- Coil-Assisted Retrograde Transvenous Obliteration (CARTO)

- Gastric variceal ligation, although this modality is falling out of favour

- Intra-gastric balloon tamponade as a bridge to further therapy

- a caveat is that a larger balloon is required to occupy the fundus of the stomach where gastric varices commonly occur

- Liver transplantation

See also

References

- ↑ Wani Z, Bhat R, Bhadoria A, Maiwall R, Choudhury A (December 2015). "Gastric varices: Classification, endoscopic and ultrasonographic management". Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 20 (12): 1200–1207. doi:10.4103/1735-1995.172990. PMC 4766829. PMID 26958057.

- ↑ "Cirrhosis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. 28 September 2020. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ↑ Wani Z, Bhat R, Bhadoria A, Maiwall R, Choudhury A (December 2015). "Gastric varices: Classification, endoscopic and ultrasonographic management". Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 20 (12): 1200–1207. doi:10.4103/1735-1995.172990. PMC 4766829. PMID 26958057.

- ↑ Wani Z, Bhat R, Bhadoria A, Maiwall R, Choudhury A (December 2015). "Gastric varices: Classification, endoscopic and ultrasonographic management". Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 20 (12): 1200–1207. doi:10.4103/1735-1995.172990. PMC 4766829. PMID 26958057.

- ↑ Goral, Vedat; Yılmaz, Nevin (3 July 2019). "Current Approaches to the Treatment of Gastric Varices: Glue, Coil Application, TIPS, and BRTO". Medicina. 55 (7): 335. doi:10.3390/medicina55070335. ISSN 1648-9144. PMC 6681371. PMID 31277322.

- ↑ Lee, Edward Wolfgang; Shahrouki, Puja; Alanis, Lourdes; Ding, Pengxu; Kee, Stephen T. (2019-06-01). "Management Options for Gastric Variceal Hemorrhage". JAMA Surgery. 154 (6): 540–548. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0407. ISSN 2168-6254. PMID 30942880. S2CID 93000660. Archived from the original on 2022-08-23. Retrieved 2022-04-07.

- ↑ Soehendra N, Nam VC, Grimm H, Kempeneers I (1986). "Endoscopic obliteration of large esophagogastric varices with bucrylate". Endoscopy. 18 (1): 25–6. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1013014. PMID 3512261. Archived from the original on 2022-08-23. Retrieved 2022-04-07.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Lee, Edward Wolfgang; Shahrouki, Puja; Alanis, Lourdes; Ding, Pengxu; Kee, Stephen T. (2019-06-01). "Management Options for Gastric Variceal Hemorrhage". JAMA Surgery. 154 (6): 540–548. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0407. ISSN 2168-6254. PMID 30942880. S2CID 93000660. Archived from the original on 2022-08-23. Retrieved 2022-04-07.

External links

| Classification |

|---|