Superior vena cava syndrome

| Superior vena cava syndrome (Mediastinal syndrome) | |

|---|---|

| Other names: SVC obstruction | |

| |

| Superior vena cava syndrome in a person with bronchogenic carcinoma. Note the swelling of his face first thing in the morning (left) and its resolution after being upright all day (right). | |

| Symptoms | Face, neck, or arm swelling, enlargement of the veins on the front of the chest, shortness of breath, cough[1] |

| Complications | Stridor, cerebral edema[1] |

| Usual onset | Over days to weeks[1] |

| Causes | Cancer, blood clot, syphilis, aortic aneurysm, fibrosing mediastinitis[1][2] |

| Risk factors | Central venous catheters, pacemaker[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging[1] |

| Treatment | Elevation of the head of the bed, steroids, stenting, bypass surgery[1][3] |

| Frequency | 15,000 cases per year (USA)[1] |

Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS), is a group of symptoms that occurs as a result of blockage of the superior vena cava ("SVC"), a large vein carrying blood into the heart.[1] Symptoms may include face, neck, or arm swelling, enlargement of the veins on the front of the chest, shortness of breath, red eyes, and cough.[1] Less commonly stridor, headache, and decreased level of consciousness may occur.[1] Onset is often over days to weeks.[1]

It most commonly occurs due to cancer or blood clot within the blood vessel.[1] The cancers most frequently involved are small cell lung cancer, non-Hodgkins lymphoma, and metastatic tumors.[1] It may also occur as a complication of intravascular devices such as central venous catheters or leads from pacemakers, certain infections such as syphilis, thoracic aneurysms, and fibrosing mediastinitis.[1][2] Diagnosis is generally by medical imaging.[1]

Initial management involves raising the head of the bed and potentially steroids.[1][3] Other efforts depends on the underlying cause.[1] If a clot is present, removal and anticoagulation therapy may be recommended.[1] Blockage by cancer may be treated with chemotherapy or radiation therapy.[1] Other efforts may include stenting or bypass surgery.[1] About 15,000 cases are estimated to occur a year in the United States.[1] The condition was first described in 1757 by Hunter.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Shortness of breath is the most common symptom, followed by face or arm swelling.[4]

Following are frequent symptoms:

- Difficulty breathing[5]

- Headache[5]

- Facial swelling[5]

- Venous distention in the neck and distended veins in the upper chest and arms[5]

- Migraines (especially if unusual to normal)

- Large decrease in lung capacity

- Facial swelling after bending/laying down

- Upper limb edema[5]

- Lightheadedness[4]

- Cough[4]

- Edema (swelling) of the neck, called the collar of Stokes[6]

- Pemberton's sign[5]

Superior vena cava syndrome usually presents more gradually with an increase in symptoms over time as malignancies increase in size or invasiveness.[4]

Cause

Over 80% of cases are caused by malignant tumors compressing the superior vena cava. Lung cancer, usually small cell carcinoma, comprises 75-80% of these cases and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, most commonly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, comprises 10-15%. Rare malignant causes include Hodgkin's lymphoma, metastatic cancers, leukemia, leiomyosarcoma of the mediastinal vessels, and plasmocytoma.[7] Syphilis and tuberculosis have also been known to cause superior vena cava syndrome.[4] SVCS can be caused by invasion or compression by a pathological process or by thrombosis in the vein itself, although this latter is less common (approximately 35% due to the use of intravascular devices).[4]

Diagnosis

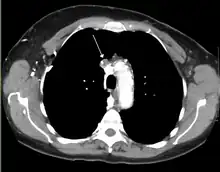

The main techniques of diagnosing SVCS are with chest X-rays (CXR), CT scans, transbronchial needle aspiration at bronchoscopy and mediastinoscopy.[5] CXRs often provide the ability to show mediastinal widening and may show the presenting primary cause of SVCS.[5] However, 16% of people with SVC syndrome have a normal chest X-ray. CT scans should be contrast enhanced and be taken on the neck, chest, lower abdomen, and pelvis.[5] They may also show the underlying cause and the extent to which the disease has progressed.[5]

Treatment

Several methods of treatment are available, mainly consisting of careful drug therapy and surgery.[4] Glucocorticoids (such as prednisone or methylprednisolone) decrease the inflammatory response to tumor invasion and edema surrounding the tumor.[4] Glucocorticoids are most helpful if the tumor is steroid-responsive, such as lymphomas. In addition, diuretics (such as furosemide) are used to reduce venous return to the heart which relieves the increased pressure.[4]

In an acute setting, endovascular stenting by an interventional radiologist may provide relief of symptoms in as little as 12–24 hours with minimal risks.

Should a patient require assistance with respiration whether it be by bag/valve/mask, bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP), continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or mechanical ventilation, extreme care should be taken. Increased airway pressure will tend to further compress an already compromised SVC and reduce venous return and in turn cardiac output and cerebral and coronary blood flow. Spontaneous respiration should be allowed during endotracheal intubation until sedation allows placement of an ET tube and reduced airway pressures should be employed when possible.

Prognosis

Symptoms are usually relieved with radiation therapy within one month of treatment.[4] However, even with treatment, 99% of patients die within two and a half years.[4] This relates to the cancerous causes of SVC found in 90% of cases. The average age of disease onset is 54 years.[4]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Seligson, MT; Surowiec, SM (January 2020). "Superior Vena Cava Syndrome". PMID 28723010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 Wilson, LD; Detterbeck, FC; Yahalom, J (3 May 2007). "Clinical practice. Superior vena cava syndrome with malignant causes". The New England journal of medicine. 356 (18): 1862–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp067190. PMID 17476012.

- 1 2 3 Zimmerman, S; Davis, M (August 2018). "Rapid Fire: Superior Vena Cava Syndrome". Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 36 (3): 577–584. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2018.04.011. PMID 30037444.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 emedicine > Superior Vena Cava Syndrome. Archived 2018-06-22 at the Wayback Machine Author: Michael S Beeson, MD, MBA, FACEP, Professor of Emergency Medicine, Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine and Pharmacy; Attending Faculty, Summa Health System. Updated: Dec 3, 2009

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Parker, Robert; Catherine Thomas; Lesley Bennett (2007). Emergencies in Respiratory Medicine. Oxford. pp. 96–7. ISBN 978-0-19-920244-7.

- ↑ define:collar of Stokes Archived 2018-06-22 at the Wayback Machine at open-resource-project.org. Retrieved Mars 2011

- ↑ Nickloes TA, Lopez Rowe V, Kallab AM, Dunlap AB (28 March 2018). "Superior Vena Cava Syndrome". Medscape. WebMD LLC. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

Further reading

- Randolph HL Wong; Joshua Chai; Calvin SH Ng; et al. (2009). "Transvenous pacing lead-induced Superior Vena Cava Syndrome: What do we know?". Surgical Practice. 13 (4): 125–126. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1633.2009.00462.x.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |