Cherry angioma

| Cherry angioma | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Campbell de Morgan spots, senile angiomas, ruby spot, cherry hemangioma[1][2][3] | |

.jpg.webp) | |

| Cherry angioma | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| Symptoms | Small red to purple dome-shaped skin bump[1] |

| Usual onset | After puberty[4] |

| Causes | Unclear[5] |

| Risk factors | Increasing age, nitrogen mustard therapy[6] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on appearance, dermoscopy[5][7] |

| Differential diagnosis | Pyogenic granuloma, petechiae, telangiectasis, other haemangiomas[5][6][8] |

| Treatment | Usually none, light electrodesication, laser ablation[6] |

| Prognosis | Excellent[3] |

| Frequency | Most adults over 30[6] |

Cherry angioma is a small red to purple dome-shaped bump in the skin.[1][5] There are usually several, typically on the chest, back, and arms, and range between 0.5mm to 6mm in size.[6][8] There are generally no symptoms; though if scratched, they may bleed.[5][8]

The cause is unclear.[5] They may appear during pregnancy and resolve afterwards.[8] They are a harmless tumor, containing an abnormal proliferation of small blood vessels.[8] Diagnosis is based on appearance, which may be supported by dermoscopy.[5][7]

Treatment is not usually necessary.[8] They may be removed with electrocauterization, light electrodesication, laser ablation, or shave excision, but this may leave a scar.[3][6] Rarely, in unclear cases, they may be removed to rule-out cancer.[5]

They are the most common kind of angioma, occurring in most adults over 30 years.[6] More tend to appear with age.[8] Males and females are affected with similar frequency.[5] Campbell de Morgan, a British surgeon, first described them in 1872.[9]

Signs and symptoms

Cherry angiomas are made up of clusters of very small blood vessels at the surface of the skin,[8] forming a small round dome ("papule"),[8] which may be flat topped . They range in colour from bright red to purple. When they first develop, they may be only a tenth of a millimeter in diameter and almost flat, appearing as small red dots. However, they then usually grow to about one or two millimeters across, and sometimes to a centimeter or more in diameter . As they grow larger, they tend to expand in thickness, and may take on the raised and rounded shape of a dome. Multiple adjoining angiomas form a polypoid angioma.[8] Because the blood vessels comprising an angioma are so close to the skin's surface, cherry angiomas may bleed profusely if they are injured.[8]

One study found that the majority of capillaries in cherry hemangiomas are fenestrated and stain for carbonic anhydrase activity.[10]

.jpg.webp) Red cherry angioma (direct vision)

Red cherry angioma (direct vision).jpg.webp) Darker red cherry angioma (direct vision)

Darker red cherry angioma (direct vision).jpg.webp) Blue-purple cherry angioma (direct vision)

Blue-purple cherry angioma (direct vision)

Cause

Cherry angiomas appear spontaneously in many people in middle age but can also, less commonly, occur in young people. They can also occur in an aggressive eruptive manner in any age. The underlying cause for the development of cherry angiomas is not understood.

Cherry angioma may occur through two different mechanisms: angiogenesis (the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing vessels), and vasculogenesis (the formation of totally new vessels, which usually occurs during embryonic and fetal development).[11]

One study published in 2010 found that a regulatory nucleic acid suppresses protein growth factors that cause vascular growth. This regulatory nucleic acid was lower in tissue samples of hemangiomas, and the growth factors were elevated, which suggests that the elevated growth factors may cause hemangiomas.[12] The study found that the level of microRNA 424 is significantly reduced in senile hemangiomas compared to normal skin resulting in increased protein expression of MEK1 and cyclin E1. By inhibiting mir-424 in normal endothelial cells they could observe the same increased protein expression of MEK1 and cyclin E1 which, important for the development of senile hemangioma, induced cell proliferation of the endothelial cells. They also found that targeting MEK1 and cyclin E1 with small interfering RNA decreased the number of endothelial cells.

A study published in 2019 identified that somatic mutations in GNAQ and GNA11 genes[13] are present in many cherry angiomas. These specific missense mutations found in hemangiomas are also associated with port-wine stains and uveal melanoma.

Chemicals and compounds that have been seen to cause cherry angiomas are mustard gas,[14][15][16][17] 2-butoxyethanol,[18] bromides,[19] and cyclosporine.[20]

A significant increase in the density of mast cells has been seen in cherry hemangiomas compared with normal skin.[21]

Diagnosis

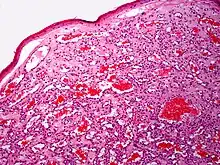

Diagnosis is by visualisation and can generally be confirmed by its appearance under a magnifying lens or under a microscope.[7] There are multiple oval to roundish thin-walled dilated small blood vessels surrounded by loose stroma; appearing bright red when the angioma is nearer to the top layer of the skin, and more blue or purple when deeper in the skin.[1][7]

.jpg.webp) Cherry angioma (dermoscopy)

Cherry angioma (dermoscopy).jpg.webp) Cherry angioma (dermoscopy)

Cherry angioma (dermoscopy).jpg.webp) Cherry angioma (dermoscopy)

Cherry angioma (dermoscopy).jpg.webp) Cherry angioma (dermoscopy)

Cherry angioma (dermoscopy).jpg.webp) Blue cherry angioma (dermoscopy)

Blue cherry angioma (dermoscopy) Cherry hemangioma(H&E stain)

Cherry hemangioma(H&E stain).jpg.webp) Cherry hemangioma(H&E stain)

Cherry hemangioma(H&E stain)

Treatment

These lesions generally do not require treatment. If they are cosmetically unappealing or are subject to bleeding angiomas may be removed by electrocautery, a process of destroying the tissue by use of a small probe with an electric current running through it.[22] Removal may cause scarring. More recently pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light (IPL) treatment has also been used.[23][24]

Future treatment based on a locally acting inhibitor of MEK1 and Cyclin E1 could possibly be an option. A natural MEK1 inhibitor is myricetin[25][26]

Prognosis

In most, the number and size of cherry angiomas increases with advancing age. They are harmless, having no relation to cancer.[8]

Epidemiology

They are the most common kind of angioma, and increase with age, occurring in nearly all adults over 30 years.[6]

History

Campbell de Morgan is the nineteenth-century British surgeon at the Middlesex Hospital, London, who first described them in a treatise in 1872.[2][27] They came to be known as 'plaques de Morgan' and initially thought to be an indication of cancer.[2] It was later associated with the term Leser–Trélat sign, a term subsequently incorrectly used to refer to seborrheic keratoses associated with cancer.[2] Before being established as harmless, various papers have falsely associated the angioma with infection and even climate.[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 DE, Elder; D, Massi; RA, Scolyer; R, Willemze (2018). "Soft tissue tumours: Cherry angioma". WHO Classification of Skin Tumours. Vol. 11 (4th ed.). Lyon (France): World Health Organization. p. 346. ISBN 978-92-832-2440-2. Archived from the original on 2022-07-11. Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5

- 1 2 3 Qadeer, HA; Singal, A; Patel, BC (January 2022). "Cherry Hemangioma". PMID 33085354.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Johnstone, Ronald B. (2017). "38. Vascular tumors". Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 690. ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-10-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Angiomas. Spider naevus | DermNet NZ". dermnetnz.org. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 James, William D.; Elston, Dirk; Treat, James R.; Rosenbach, Misha A.; Neuhaus, Isaac (2020). "28. Dermal and subcutaneous tumors". Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (13th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 593–594. ISBN 978-0-323-54753-6. Archived from the original on 2021-10-20. Retrieved 2021-10-19.

- 1 2 3 4 Marghoob, Ashfaq A.; Braun, Ralph; Jaimes, Natalia (2022). Atlas of Dermoscopy: Third Edition (3rd ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-429-48787-3. Archived from the original on 2022-08-14. Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Stockman, David L. (2016). "Cherry angioma". Diagnostic pathology. Vascular. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. pp. 3.4–3.5. ISBN 978-0-323-37674-7. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2019-05-03.

- ↑ Mulliken, John B. (2013). "13. Capillary malformations, hyperkeratotic stains, telangiectasias, and miscellaneous vascular blots". In Mulliken, John B.; Burrows, Patricia E.; Fishman, Steven J. (eds.). Mulliken and Young's Vascular Anomalies: Hemangiomas and Malformations (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 551. ISBN 978-0-19-972254-9. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- ↑ Eichhorn, M; Jungkunz, W; Wörl, J; Marsch, WC (1994). "Carbonic anhydrase is abundant in fenestrated capillaries of cherry hemangioma". Acta Dermato-venereologica. 74 (1): 51–3. doi:10.2340/00015555745153 (inactive 2021-01-11). PMID 7908484.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link) - ↑ Kishimoto, Saburo; Hideya Takenaka; Hideya Takenaka; Hideya Takenaka; Hirokazu Yasuno (2000). "Glomeruloid hemangioma in POEMS syndrome shows two different immunophenotypic endothelial cells". Cutaneous Pathology. 27 (2): 87–92. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2000.027002087.x. PMID 10678704. S2CID 25150654.

- ↑ Nakashima, T; Jinnin, M; Etoh, T; Fukushima, S; Masuguchi, S; Maruo, K; Inoue, Y; Ishihara, T; Ihn, H (2010). Egles, Christophe (ed.). "Down-regulation of mir-424 contributes to the abnormal angiogenesis via MEK1 and cyclin E1 in senile hemangioma: its implications to therapy". PLOS ONE. 5 (12): e14334. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...514334N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014334. PMC 3001869. PMID 21179471.

- ↑ Klebanov, Nikolai; Lin, William M.; Artomov, Mykyta; Shaughnessy, Michael; Njauw, Ching-Ni; Bloom, Romi; Eterovic, Agda Karina; Chen, Ken; Kim, Tae-Beom (2019-01-02). "Use of Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing to Identify Activating Hot Spot Mutations in Cherry Angiomas". JAMA Dermatology. 155 (2): 211–215. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4231. ISSN 2168-6084. PMC 6440195. PMID 30601876.

- ↑ Firooz, Alireza; Komeili, Ali; Dowlati, Yahya (1999). "Eruptive melanocytic nevi and cherry angiomas secondary to exposureto sulfur mustard gas". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 40 (4): 646–7. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70460-3. PMID 10188695.

- ↑ Hefazi, Mehrdad; Maleki, Masoud; Mahmoudi, Mahmoud; Tabatabaee, Abbas; Balali-Mood, Mahdi (2006). "Delayed complications of sulfur mustard poisoning in the skin and the immune system of Iranian veterans 16–20 years after exposure". International Journal of Dermatology. 45 (9): 1025–31. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.03020.x. PMID 16961503. S2CID 38801029.

- ↑ Ma, Hui-Jun; Zhao, Guang; Shi, Fei; Wang, Yi-Xia (2006). "Eruptive cherry angiomas associated with vitiligo: Provoked by topical nitrogen mustard?". The Journal of Dermatology. 33 (12): 877–9. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00200.x. PMID 17169094. S2CID 6811229.

- ↑ Emadi, Seyed Naser; Hosseini-Khalili, Alireza; Soroush, Mohammad Reza; Davoodi, Seyed Masoud; Aghamiri, Seyed Samad (2008). "Mustard gas scarring with specific pigmentary, trophic and vascular characteristics (case report, 16-year post-exposure)". Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 69 (3): 574–6. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2007.01.003. PMID 17382390.

- ↑ Raymond, Lawrence W.; Williford, Linda S.; Burke, William A. (1998). "Eruptive Cherry Angiomas and Irritant Symptoms After One Acute Exposure to the Glycol Ether Solvent 2-Butoxyethanol". Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine. 40 (12): 1059–64. doi:10.1097/00043764-199812000-00005. PMID 9871882.

- ↑ Cohen, Arnon D.; Cagnano, Emanuela; Vardy, Daniel A. (2001). "Cherry Angiomas Associated with Exposure to Bromides". Dermatology. 202 (1): 52–3. doi:10.1159/000051587. PMID 11244231. S2CID 45485034.

- ↑ De Felipe, I.; Redondo, P (1998). "Eruptive Angiomas After Treatment With Cyclosporine in a Patient With Psoriasis". Archives of Dermatology. 134 (11): 1487–8. doi:10.1001/archderm.134.11.1487. PMID 9828895.

- ↑ Hagiwara, K; Khaskhely, NM; Uezato, H; Nonaka, S (1999). "Mast cell "densities" in vascular proliferations: a preliminary study of pyogenic granuloma, portwine stain, cavernous hemangioma, cherry angioma, Kaposi's sarcoma, and malignant hemangioendothelioma". The Journal of Dermatology. 26 (9): 577–86. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.1999.tb02052.x. PMID 10535252. S2CID 40976538.

- ↑ Aversa, AJ; Miller Of, 3rd (1983). "Cryo-curettage of cherry angiomas". The Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 9 (11): 930–1. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1983.tb01042.x. PMID 6630708.

- ↑ Dawn, G.; Gupta, G. (2003). "Comparison of potassium titanyl phosphate vascular laser and hyfrecator in the treatment of vascular spiders and cherry angiomas". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 28 (6): 581–3. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01352.x. PMID 14616818. S2CID 13497344.

- ↑ Fodor, Lucian; Ramon, Ytzhack; Fodor, Adriana; Carmi, Nurit; Peled, Isaac J.; Ullmann, Yehuda (2006). "A Side-by-Side Prospective Study of Intense Pulsed Light and Nd:YAG Laser Treatment for Vascular Lesions". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 56 (2): 164–70. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000196579.14954.d6. PMID 16432325. S2CID 43324812.

- ↑ Lee, KW; Kang, NJ; Rogozin, EA; Kim, HG; Cho, YY; Bode, AM; Lee, HJ; Surh, YJ; et al. (2007). "Myricetin is a novel natural inhibitor of neoplastic cell transformation and MEK1". Carcinogenesis. 28 (9): 1918–27. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgm110. PMID 17693661.

- ↑ Kim, JE; Kwon, JY; Lee, DE; Kang, NJ; Heo, YS; Lee, KW; Lee, HJ (2009). "MKK4 is a novel target for the inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression by myricetin". Biochemical Pharmacology. 77 (3): 412–21. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2008.10.027. PMID 19026990.

- ↑ Rosser, E. M. (1983). "Campbell De Morgan and his Spots" (PDF). Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 65: 266–268. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-08-14. Retrieved 2022-08-11.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |