Tropical sprue

| Tropical sprue | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Post‐infectious tropical malabsorption[1] | |

| Video explanation | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Liquid, frequent, and bad smelling stool, bloating, weight loss, inflammed tongue[2][1] |

| Complications | Vitamin deficiencies, low protein levels, electrolyte abnormalities[2][1] |

| Duration | Long-term[1] |

| Causes | Unknown[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, poor absorption of at least two types of nutrients, small bowel biopsy, and ruling out other potential causes[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Irritable bowel syndrome, environmental enteropathy, active infections, HIV/AIDS, Celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease[2][1] |

| Treatment | antibiotics, folic acid, and vitamin B12.[2] |

| Frequency | Unclear[2] |

Tropical sprue is a malabsorption disease found in tropical regions.[2] Symptoms include liquid, frequent, and bad smelling stool, bloating, weight loss, an inflammed tongue, and vitamin deficiencies.[2][1] Vitamin deficiencies may include vitamin A, resulting in trouble seeing at night, and vitamin B12, resulting in anemia.[1] Low protein levels and electrolyte abnormalities may also occur.[1]

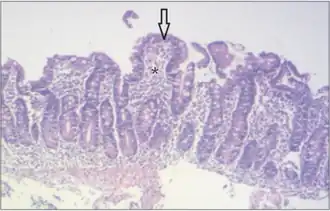

The cause is unknown.[1] It occurs following about 10% of cases of gastroenteritis.[2] The underlying mechanism involves flattening of the villi and inflammation of the lining of the small intestine.[1] Diagnosis is based on symptoms, poor absorption of at least two types of nutrients, small bowel biopsy, ruling out other potential causes, and improvement with antibiotics and folic acid.[2] Other conditions that may cause similar symptoms include active infections, HIV/AIDS, Celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and pancreatic disease.[1] Similar changes to the bowels without symptoms is known as environmental enteropathy.[1]

Treatment involves the use of antibiotics, such as tetracycline, together with folic acid and vitamin B12.[2][3] Historically tropical sprue appears to have been common in parts of Asia, Central America, and South America.[2][1] How frequently it currently occurs is developing regions of the world; however, is controversial.[2] While it previous occurred in outbreaks, this appears to be less common with improved access to antibiotics and clean water.[1] Early descriptions of the condition date from more than 2,000 years ago in the Indian text Charaka Samhita.[1] The current name for the condition came into use in 1880.[1]

Signs and symptoms

The illness usually starts with an attack of acute diarrhoea, fever and malaise following which, after a variable period, the patient settles into the chronic phase of diarrhoea, steatorrhoea, weight loss, anorexia, malaise, and nutritional deficiencies.[1][3] The symptoms of tropical sprue are:

- Diarrhoea

- Steatorrhoea or fatty stool (often foul-smelling and whitish in colour)

- Indigestion

- Cramps

- Weight loss and malnutrition

- Fatigue

Left untreated, nutrient and vitamin deficiencies may develop.[1] These deficiencies may have these symptoms:

- Vitamin A deficiency: hyperkeratosis or skin scales

- Vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiencies: anaemia

- Vitamin D and calcium deficiencies: spasm, bone pain, numbness, and tingling sensation

- Vitamin K deficiency: bruises

Cause

The cause of tropical sprue is not known.[1] It may be caused by persistent bacterial, viral, amoebal, or parasitic infections.[4] Folic acid deficiency, effects of malabsorbed fat on intestinal motility, and persistent small intestinal bacterial overgrowth may combine to cause the disorder.[5] A link between small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and tropical sprue has been proposed to be involved in the aetiology of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).[6]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of tropical sprue can be complicated because many diseases have similar symptoms. The following investigation results are suggestive:

- Abnormal flattening of villi and inflammation of the lining of the small intestine, observed during an endoscopic procedure.

- Presence of inflammatory cells (most often lymphocytes) in the biopsy of small intestine tissue.

- Low levels of vitamins A, B12, E, D, and K, as well as serum albumin, calcium, and folate, revealed by a blood test.

- Excess fat in the feces (steatorrhoea).

- Thickened small bowel folds seen on imaging.

Tropical sprue is largely limited to within about 30 degrees north and south of the equator. Recent travel to this region is a key factor in diagnosing this disease in residents of countries outside of that geographical region.[1]

Other conditions which can resemble tropical sprue need to be differentiated.[2] Coeliac disease (also known as coeliac sprue or gluten sensitive enteropathy), has similar symptoms to tropical sprue, with the flattening of the villi and small intestine inflammation and is caused by an autoimmune disorder in genetically susceptible individuals triggered by ingested gluten. Malabsorption can also be caused by protozoan infections, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, immunodeficiency, chronic pancreatitis and inflammatory bowel disease.[1] Environmental enteropathy is a less severe, subclinical condition similar to tropical sprue.[1]

Prevention

Preventive measures for visitors to tropical areas where the condition exists include steps to reduce the likelihood of gastroenteritis. These may comprise using only bottled water for drinking, brushing teeth, and washing food, and avoiding fruits washed with tap water (or consuming only peeled fruits, such as bananas and oranges). Basic sanitation is necessary to reduce fecal-oral contamination and the impact of environmental enteropathy in the developing world.[1]

Treatment

Once diagnosed, tropical sprue can be treated by a course of the antibiotic tetracycline or sulphamethoxazole/trimethoprim (co-trimoxazole) for 3 to 6 months.[1][7] Supplementation of vitamins B12 and folic acid improves appetite and leads to a gain in weight.[2][8]

Prognosis

The prognosis for tropical sprue may be excellent after treatment. It usually does not recur in people who get it during travel to affected regions. The recurrence rate for natives is about 20%,[1] but another study showed changes can persist for several years.[9]

Epidemiology

Tropical sprue is common in the Caribbean, Central and South America, and India and southeast Asia.[1] In the Caribbean, it appeared to be more common in Puerto Rico and Haiti. Epidemics in southern India have occurred.[1]

History

The disease was first described by William Hillary[10] in 1759 in Barbados.[11]

Tropical sprue was responsible for one-sixth of all casualties sustained by the Allied forces in India and Southeast Asia during World War II.[1]

The use of folic acid and vitamin B12 in the treatment of tropical sprue was promoted in the late 1940s by Tom Spies of the University of Alabama, while conducting his research in Cuba and Puerto Rico.[12][13][14]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Ramakrishna BS, Venkataraman S, Mukhopadhya A (2006). "Tropical malabsorption". Postgrad Med J. 82 (974): 779–87. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2006.048579. PMC 2653921. PMID 17148698.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Ghoshal UC, Srivastava D, Verma A, Ghoshal U (2014). "Tropical sprue in 2014: the new face of an old disease". Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 16 (6): 391. doi:10.1007/s11894-014-0391-3. PMC 7088824. PMID 24781741.

- 1 2 Korpe PS, Petri WA (2012). "Environmental enteropathy: critical implications of a poorly understood condition". Trends Mol Med. 18 (6): 328–36. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2012.04.007. PMC 3372657. PMID 22633998.

- ↑ Cook GC (1997). "'Tropical sprue': some early investigators favoured an infective cause, but was a coccidian protozoan involved?". Gut. 40 (3): 428–9. doi:10.1136/gut.40.3.428. PMC 1027098. PMID 9135537.

- ↑ Cook GC (1984). "Aetiology and pathogenesis of postinfective tropical malabsorption (tropical sprue)". Lancet. 1 (8379): 721–3. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92231-1. PMID 6143049.

- ↑ Ghoshal UC, Gwee KA (2017). "Post-infectious IBS, tropical sprue and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: the missing link". Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 14 (7): 435–441. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2017.37. PMID 28513629.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ Batheja MJ, Leighton J, Azueta A, Heigh R (2010). "The Face of Tropical Sprue in 2010". Case Rep Gastroenterol. 4 (2): 168–172. doi:10.1159/000314231. PMC 2929410. PMID 20805939.

- ↑ Klipstein FA, Corcino JJ (1977). "Factors responsible for weight loss in tropical sprue". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 30 (10): 1703–8. doi:10.1093/ajcn/30.10.1703. PMID 910746.

- ↑ Rickles FR, Klipstein FA, Tomasini J, Corcino JJ, Maldonado N (1972). "Long-term follow-up of antibiotic-treated tropical sprue". Ann. Intern. Med. 76 (2): 203–10. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-76-2-203. PMID 5009590.

- ↑ Bartholomew C (November 1989). "William Hillary and sprue in the Caribbean: 230 years later". Gut. 30 (Special issue): 17–21. doi:10.1136/gut.30.spec_no.17. PMC 1440696. PMID 2691344.

- ↑ Hillary, William (1759). Observations on the Changes of the Air and the Concomitant Epidemical Diseases in the Island of Barbados: To which is Added a Treatise on the Putrid Bilious Fever, Commonly Called the Yellow Fever. pp. 277–281. Archived from the original on 2021-08-27. Retrieved 2017-06-03.

- ↑ Spies TD, Suarez RM, Suarez RM, Hernandez-Morales F (1946). "The Therapeutic Effect of Folic Acid in Tropical Sprue". Science. 104 (2691): 75–6. doi:10.1126/science.104.2691.75. PMID 17769104.

- ↑ SUAREZ RM, SPIES TD (1949). "A note on the effectiveness of vitamin B12 in the treatment of tropical sprue in relapse". Blood. 4 (10): 1124–30. PMID 18139385.

- ↑ "Dr. Spies Receives Distinguished Service Medal". Journal of the American Medical Association. 164 (8): 878. 1957. doi:10.1001/jama.1957.02980080048013.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |