Femoral hernia

| Femoral hernia | |

|---|---|

| |

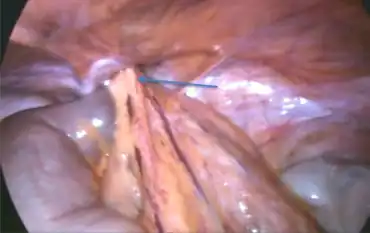

| Incarcerated omental contents in the femoral hernia arrow | |

| Specialty | General surgery |

Femoral hernias occur just below the inguinal ligament, when abdominal contents pass through a naturally occurring weakness in the abdominal wall called the femoral canal. Femoral hernias are a relatively uncommon type, accounting for only 3% of all hernias. While femoral hernias can occur in both males and females, almost all develop in women due to the increased width of the female pelvis.[1] Femoral hernias are more common in adults than in children. Those that do occur in children are more likely to be associated with a connective tissue disorder or with conditions that increase intra-abdominal pressure. Seventy percent of pediatric cases of femoral hernias occur in infants under the age of one.[1]

Definitions

A hernia is caused by the protrusion of a viscus (in the case of groin hernias, an intra-abdominal organ) through a weakness in the abdominal wall. This weakness may be inherent, as in the case of inguinal, femoral and umbilical hernias. On the other hand, the weakness may be caused by previous surgical incision through the muscles and fascia in the area; this is termed an incisional hernia.

A femoral hernia may be either reducible or irreducible, and each type can also present as obstructed and/or strangulated.[2]

A reducible femoral hernia occurs when a femoral hernia can be pushed back into the abdominal cavity, either spontaneously or with manipulation. However, it is more likely to occur spontaneously. This is the most common type of femoral hernia and is usually painless.

An irreducible femoral hernia occurs when a femoral hernia cannot be completely reduced, typically due to adhesions between the hernia and the hernial sac. This can cause pain and a feeling of illness.

An obstructed femoral hernia occurs when a part of the intestine involved in the hernia becomes twisted, kinked, or constricted, causing an intestinal obstruction.

A strangulated femoral hernia occurs when a constriction of the hernia limits or completely obstructs blood supply to part of the bowel involved in the hernia. Strangulation can occur in all hernias, but is more common in femoral and inguinal hernias due to their narrow "weaknesses" in the abdominal wall. Nausea, vomiting, and severe abdominal pain are characteristics of a strangulated hernia. This is a medical emergency as the loss of blood supply to the bowel can result in necrosis (tissue death) followed by gangrene (tissue decay). This is a life-threatening condition requiring immediate surgery.[3]

The term incarcerated femoral hernia is sometimes used, but may have different meanings to different authors and physicians. For example: "Sometimes the hernia can get stuck in the canal and is called an irreducible or incarcerated femoral hernia."[4] "The term incarcerated is sometimes used to describe an [obstructed] hernia that is irreducible but not strangulated. Thus, an irreducible, obstructed hernia can also be called an incarcerated one."[5] "Incarcerated hernia is a hernia that cannot be reduced. These may lead to bowel obstruction but are not associated with vascular compromise."[6]

A hernia can be described as reducible if the contents within the sac can be pushed back through the defect into the peritoneal cavity, whereas with an incarcerated hernia, the contents are stuck in the hernia sac.[7] However, the term incarcerated seems to always imply that the femoral hernia is at least irreducible.

Signs and symptoms

Femoral hernias typically present as a groin lump or bulge, which may differ in size during the day, based on internal pressure variations of the intestine. This lump is typically retort shaped. The bulge or lump is typically smaller or may disappear completely in the prone position.[8]

They may or may not be associated with pain. Often, they present with a varying degree of complication ranging from irreducibility through intestinal obstruction to frank gangrene of contained bowel. The incidence of strangulation in femoral hernias is high. A femoral hernia has often been found to be the cause of unexplained small bowel obstruction.

The cough impulse is often absent and is not relied on solely when making a diagnosis of femoral hernia. The lump is more globular than the pear-shaped lump of the inguinal hernia. The bulk of a femoral hernia lies below an imaginary line drawn between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle (which essentially represents the inguinal ligament) whereas an inguinal hernia starts above this line. Nonetheless, it is often impossible to distinguish the two preoperatively.

Anatomy

The femoral canal is located below the inguinal ligament on the lateral aspect of the pubic tubercle. It is bounded by the inguinal ligament anteriorly, pectineal ligament posteriorly, lacunar ligament medially, and the femoral vein laterally. It normally contains a few lymphatics, loose areolar tissue, and occasionally a lymph node called Cloquet's node. The function of this canal appears to be to allow the femoral vein to expand when necessary to accommodate increased venous return from the leg during periods of activity.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is largely a clinical one, generally done by physical examination of the groin. However, in obese patients, imaging in the form of ultrasound, CT, or MRI may aid in the diagnosis. For example, an abdominal X-ray showing small bowel obstruction in a female patient with a painful groin lump needs no further investigation.

Several other conditions have a similar presentation and must be considered when forming the diagnosis: inguinal hernia, an enlarged femoral lymph node, aneurysm of the femoral artery, dilation of the saphenous vein, athletic pubalgia, and an abscess of the psoas.[9][10]

Classification

Several subtypes of femoral hernia have been described.[11]

| 'Retrovascular hernia (Narath’s hernia)' | The hernial sac emerges from the abdomen within the femoral sheath but lies posteriorly to the femoral vein and artery, visible only if the hip is congenitally dislocated. |

| 'Serafini's hernia' | The hernial sac emerges behind femoral vessels (E). |

| 'Velpeau hernia' | The hernial sac lies in front of the femoral blood vessels in the groin (B). |

| 'External femoral hernia of Hesselbach and Cloquet' | The neck of the sac lies lateral to the femoral vessels ((A) and (F)). |

| 'Transpectineal femoral hernia of Laugier' | The hernial sac transverses the lacunar ligament or the pectineal ligament of Cooper (D). |

| 'Callisen’s or Cloquet's hernia' | The hernial sac descends deep to the femoral vessels through the pectineal fascia (F). |

| 'Béclard's hernia' | The hernial sac emerges through the saphenous opening carrying the cribriform fascia with it. |

| 'De Garengeot's hernia' | This is a vermiform appendix trapped within the hernial sac. |

Management

Femoral hernias, like most other hernias, usually need operative intervention. This should ideally be done as an elective (non-emergency) procedure. However, because of the high incidence of complications, femoral hernias often need emergency surgery.

Surgery

Some surgeons choose to perform "key-hole" or laparoscopic surgery (also called minimally invasive surgery) rather than conventional "open" surgery. With minimally invasive surgery, one or more small incisions are made that allow the surgeon to use a surgical camera and small tools to repair the hernia.[12]

Either open or minimally invasive surgery may be performed under general or regional anesthesia, depending on the extent of the intervention needed. Three approaches have been described for open surgery:

- Lockwood’s infra-inguinal approach

- Lotheissen‘s trans-inguinal approach

- McEvedy’s high approach

The infra-inguinal approach is the preferred method for elective repair. The trans-inguinal approach involves dissecting through the inguinal canal and carries the risk of weakening the inguinal canal. McEvedy’s approach is preferred in the emergency setting when strangulation is suspected. This allows better access to and visualization of the bowel for possible resection. In any approach, care should be taken to avoid injury to the urinary bladder which is often a part of the medial part of the hernial sac.

Repair is either performed by suturing the inguinal ligament to the pectineal ligament using strong non-absorbable sutures or by placing a mesh plug in the femoral ring. With either technique care should be taken to avoid any pressure on the femoral vein.

Postoperative outcome

Patients undergoing elective surgical repair do very well and may be able to go home the same day. However, emergency repair carries a greater morbidity and mortality rate and this is directly proportional to the degree of bowel compromise.

Epidemiology

Femoral hernias are more common in multiparous females, which results from elevated intra-abdominal pressure that dilates the femoral vein and in turn stretches femoral ring. Such constant pressure causes preperitoneal fat to insinuate in the femoral ring, a consequence of which is development of a femoral peritoneal sac.[13]

References

- 1 2 Rastegari, Esther Csapo (2009). "Femoral hernia repair". Advameg, Inc. Archived from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 10 Sep 2009.

- ↑ "Inguinal hernias". Pulsenotes. 24 March 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-03-24. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ↑ "Femoral hernia". MedlinePlus. 27 Aug 2009. Archived from the original on 13 September 2009. Retrieved 9 Sep 2009.

- ↑ "Hernia". Bupa. April 2008. Archived from the original on 12 May 2009. Retrieved 10 Sep 2009.

- ↑ "Hernia". freshspring web solutions. 2009. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 10 Sep 2009.

- ↑ "Femoral and inguinal hernia". mdconsult.com. 19 Sep 2007. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 10 Sep 2009.

- ↑ de Virgilio, C., Frank, P. and Grigorian, A. (2015). Surgery. New York, NY: Springer New York.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-09-24. Retrieved 2014-01-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Femoral Hernia". Teach Me Surgery. 24 March 2018. Archived from the original on 25 March 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ↑ "Femoral hernias". Universitäts Klinikumbonn. 24 March 2018. Archived from the original on 2002-11-18. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ↑ Papanikitas, Joseph; Robert P Sutcliffe; Ashish Rohatgi; Simon Atkinson (July 2008). "Bilateral Retrovascular Femoral Hernia". Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 90 (5): 423–424. doi:10.1308/003588408X301235. PMC 2645754. PMID 18634743.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Hachisuka, Takehiro (1 October 2003). "Femoral hernia repair" (PDF). Surgical Clinics of North America. 83 (5): 1189–1205. doi:10.1016/S0039-6109(03)00120-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-21. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Surgery Encyclopaedia Archived 2019-02-14 at the Wayback Machine