Rectococcygeal muscle

| Rectococcygeal muscle | |

|---|---|

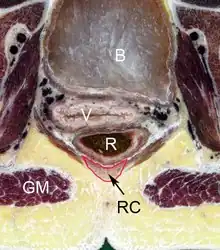

Transverse section through pelvic region of a Chinese female. The rectococcygeal muscle (RC) is indicated by arrow and outlined in red. Other features are the bladder (B), vagina (V), rectum (R) and gluteus maximus (GM). | |

| Details | |

| Origin | Coccygeal vertebrae |

| Insertion | Rectal longitudinal muscles |

| Nerve | Inferior hypogastric plexus |

| Actions | Lifts and secures rectum during defecation. |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Musculus rectococcygeus |

| TA98 | A05.7.04.011 |

| TA2 | 3847 |

| FMA | 77237 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

The rectococcygeal muscles are two bands of smooth muscle tissue arising from the 2nd and 3rd coccygeal vertebrae, and passing downward and forward to blend with the rectal longitudinal smooth muscle fibers on the posterior wall of the anal canal.[1]

Structure

The rectococcygeal muscles are composed of smooth muscle and run from the anterior surface of the 2nd and 3rd coccygeal vertebrae down the posterior wall of the rectum as a triangular shaped muscle before branching and inserting among the various muscles and fascial structures associated with the pelvic diaphragm and anal canal and collectively called longitudinal anal muscles.[1][2]

Variation

There are some differences in the retrococcygeal muscle architecture between males and females. In males the muscle inserts with the fascia of the levator ani to either side of the rectum or to other fascial elements of the pelvic diaphragm. In females the rectococcygeal muscle additionally runs around the sides of the rectum to connect to the rectovaginal fascia of the posterior vaginal wall.[3][4] There is also evidence suggesting that the retrococcygeal muscles are ~2-fold thicker in females.[1]

Innervation

The rectoccygeal muscles are innervated by autonomic nerves associated with the inferior hypogastric plexus.

Function

The rectococcygeal muscles form part of the complex arrangement of muscle surrounding the rectum, sometimes termed the anal-sphincter complex, which act to stabilise and support the anal canal during defecation. The rectococcygeal muscle acts to lift the sphincter, thereby effectively shortening the rectum and aiding evacuation.[5]

Other animals

In many animals with tails, such as horses and dogs, the rectococcygeal muscles are involved in the response to the raising of the tail during defecation.[6] In tailed animals the muscle attaches to vertebrae in a more caudal position than in humans due to the additional vertebrae in the tail, in dogs there are connections to the 5th and 6th caudal vertebrae and in horses to the 4th or 5th.[6][7] The rectococcygeal muscle in the rabbit is notable for being one of the fastest contracting mammalian smooth muscles known.[8][9]

Other images

Pelvic region showing m. rectococcygeus.

Pelvic region showing m. rectococcygeus.

External links

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1186 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1186 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- 1 2 3 Wu Y, Dabhoiwala NF, Hagoort J, et al. 3D Topography of the Young Adult Anal Sphincter Complex Reconstructed from Undeformed Serial Anatomical Sections. Souglakos J, ed. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0132226. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132226

- ↑ Kim JH, Kinugasa Y, Yu HC, Murakami G, Abe S, Cho BH (2015). "Lack of striated muscle fibers in the longitudinal anal muscle of elderly Japanese: a histological study using cadaveric specimens". Int J Colorectal Dis. 30 (1): 43–9. doi:10.1007/s00384-014-2038-0. PMID 25331031. S2CID 37235615.

- ↑ Lierse W, Applied Anatomy of the Pelvis, Springer-Verlag, 1987, p.271. ISBN 9783642713682

- ↑ Kinugasa Y, Arakawa T, Abe H, Rodríguez-Vázquez JF, Murakami G, Sugihara K (2013). "Female longitudinal anal muscles or conjoint longitudinal coats extend into the subcutaneous tissue along the vaginal vestibule: a histological study using human fetuses". Yonsei Med. J. 54 (3): 778–84. doi:10.3349/ymj.2013.54.3.778. PMC 3635647. PMID 23549829.

- ↑ Nout YS, Leedy GM, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC (2006). "Alterations in eliminative and sexual reflexes after spinal cord injury: defecatory function and development of spasticity in pelvic floor musculature". Autonomic Dysfunction After Spinal Cord Injury. Prog. Brain Res. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 152. pp. 359–72. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(05)52024-7. ISBN 9780444519252. PMID 16198713.

- 1 2 Evans HE, de Lahunta A, Miller's Anatomy of the Dog, Elsevier Health Sciences, 2013, p.326. ISBN 9780323266239

- ↑ Budras KD, Sack WO, Rock S, Anatomy of the Horse: An Illustrated Text, Schlütersche, 2003. p.93. ISBN 0723419213

- ↑ Malmqvist U, Arner A (1991). "Correlation between isoform composition of the 17 kDa myosin light chain and maximal shortening velocity in smooth muscle". Pflügers Arch. 418 (6): 523–30. doi:10.1007/bf00370566. PMID 1834987. S2CID 8602764.

- ↑ Andersson KE, Arner A (2004). "Urinary bladder contraction and relaxation: physiology and pathophysiology". Physiol. Rev. 84 (3): 935–86. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.324.7009. doi:10.1152/physrev.00038.2003. PMID 15269341.