Secondary somatosensory cortex

The human secondary somatosensory cortex (S2, SII) is a region of cortex in the parietal operculum on the ceiling of the lateral sulcus.

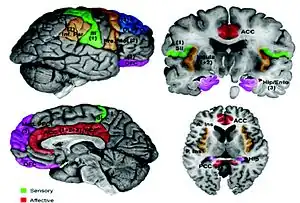

Region S2 was first described by Adrian in 1940, who found that feeling in cats' feet was not only represented in the primary somatosensory cortex (S1) but also in a second region adjacent to S1.[1] In 1954, Penfield and Jasper evoked somatosensory sensations in human patients during neurosurgery by electrically stimulating the ceiling of the lateral sulcus, which lies adjacent to S1, and their findings were confirmed in 1979 by Woolsey et al. using evoked potentials and electrical stimulation.[2][3] Experiments involving ablation of the second somatosensory cortex in primates indicate that this cortical area is involved in remembering the differences between tactile shapes and textures.[4][5] Functional neuroimaging studies have found S2 activation in response to light touch, pain, visceral sensation, and tactile attention.[6]

In monkeys, apes and hominids, including humans, region S2 is divided into several "areas". An area at the entrance to the lateral sulcus, adjoining the primary somatosensory cortex (S1), is called the parietal ventral (PV) area. Posterior to PV is the secondary somatosensory area (area S2, which must not be confused with "region S2" which designates the entire secondary somatosensory cortex, of which area S2 is a part). Deeper in the lateral sulcus lies the ventral somatosensory (VS) area, whose outer edge adjoins areas PV and S2 and inner edge adjoins the insular cortex.

In humans, the secondary somatosensory cortex includes parts of Brodmann area (BA) 40 and 43.[7]

Areas PV and S2 both map the body surface. Functional neuroimaging in humans has revealed that in areas PV and S2 the face is represented near the entrance to the lateral sulcus, and the hands and feet deeper in the fissure. Individual neurons in areas PV and S2 receive input from wide areas of the body surface (they have large "receptive fields"), and respond readily to stimuli such as wiping a sponge over a large area of skin.[7]

Area PV connects densely with BA 5 and the premotor cortex. Area S2 is interconnected with BA 1 and densely so with BA 3b, and projects to PV, BA 7b, insular cortex, amygdala and hippocampus. Areas S2 in the left and right hemispheres are densely interconnected, and stimulation on one side of the body will activate area S2 in both hemispheres.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ Adrian, ED (1940). "Double representation of the feet in the sensory cortex of the cat". Journal of Physiology. 98: 16–18.

- ↑ Penfield, W; Jasper, H (1954). Epilepsy and functional anatomy of the human brain. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co. ISBN 978-0-316-69833-7.

- ↑ Woolsey CN, Erickson TC, Gilson WE (October 1979). "Localization in somatic sensory and motor areas of human cerebral cortex as determined by direct recording of evoked potentials and electrical stimulation". J. Neurosurg. 51 (4): 476–506. doi:10.3171/jns.1979.51.4.0476. PMID 479934.

- ↑ Ridley, R.M. and Ettlinger, G. (1976). "Impaired tactile learning and retention after removals of the second somatic sensory projection cortex (S11) in the monkey". Brain Research. 109 (3): 656–660. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(76)90048-2.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Ridley, R.M. and Ettlinger, G. (1978). "Further evidence of impaired tactile learning after removals of the second somatic sensory projection cortex (S11) in the monkey". Exp. Brain Res. 31 (4): 475–488. doi:10.1007/bf00239806.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Eickhoff SB, Schleicher A, Zilles K, Amunts K (February 2006). "The human parietal operculum. I. Cytoarchitectonic mapping of subdivisions". Cereb. Cortex. 16 (2): 254–67. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhi105. PMID 15888607.

- 1 2 3 Benarroch, Eduardo E. (2006). Basic neurosciences with clinical applications. Edinburgh: Butterworth Heinemann/Elsevier. pp. 441–2. ISBN 978-0-7506-7536-9.