Seoul orthohantavirus

| Seoul orthohantavirus | |

|---|---|

| |

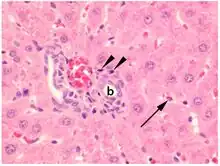

| Photomicrograph of liver parenchyma of a natural Seoul virus | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Ellioviricetes |

| Order: | Bunyavirales |

| Family: | Hantaviridae |

| Genus: | Orthohantavirus |

| Species: | Seoul orthohantavirus |

| Strains | |

| |

Seoul orthohantavirus (SEOV) is a member of the Orthohantavirus family of rodent-borne viruses and is one of the 4 hantaviruses that are known to be able to cause Hantavirus hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS).[1][2] It is an Old World hantavirus; a negative sense, single-stranded, tri-segmented RNA virus.

Seoul virus is found in Rattus species rats, most commonly Rattus norvegicus, but occasionally Rattus rattus.[3] The two distinct hantaviruses have been identified in Korea in 1976, from Apodemus agrarius, and in 1980, from Rattus norvegicus. In 1994, a genetically different hantavirus was identified from Apodemus peninsulae.[4] Rats do not show physiological symptoms when carrying the virus, but humans can be infected through exposure to infected rodent body fluids (blood, saliva, urine), exposure to aerosolized rat excrement, or bites from infected rats.[1] When rodent bedding or urine is stirred up by either natural causes or human-caused disturbances, small particles are made to be airborne. This can be breathed in and cause an infection in humans. There is currently no evidence of human-to-human transmission of SEOV, only rodent-human transmission.[5]

Seoul virus was first described by Dr. Lee Ho-Wang (Ho-Wang Lee), a Korean virologist. As the infection was first found in an apartment in Seoul, the virus was named "Seoul Virus".

Virology

Virus structure and genome

SEOV, along with all other hantaviruses, is a negative sense, single-stranded RNA virus. Its genome has three different segments: S (small), M (medium), and L (large).[6] The virus is pleomorphic, having various shapes, but often is seen as spherical, with its two surface glycoproteins arranged in rows. Inside this sphere, the three RNA segments are arranged as circles, coated in the virus' N (nucleocapsid) protein and attached to the L protein. The 5' and 3' ends of the genome segments match up, creating a panhandle structure. This base pairing occurs in all hantavirus species, with the panhandle structure and sequence being unique to each particular species, of course with some similarities and overlap between species, including an eight nucleotide consensus sequence.[7][6]

Viral proteins

There are four major viral proteins, the two surface glycoproteins (Gn and Gc), the nucleocapsid protein (N), and the viral polymerase (L).

The Gn and Gc proteins exist on the surface of the mature virus as spikes in highly ordered rows, with each spike having four Gn/Gc heterodimers.[6][8] Interactions between the spikes are thought to cause viral budding into the Golgi apparatus.[9] These surface glycoproteins are also responsible for the attachment of the virus to its target host cell. Gn and Gc spikes attach to β3 integrins and co-receptors on the target cell surface.[8][10]

Transmission

Rodent Populations

The SEOV is transmitted among the rats rapidly and has been detected in rat populations that reside in port cities worldwide.[11]

Human Populations

There are no instances of SEOV transmission from human to human.

Epidemiology

Most human infections are recorded in Asia.[5] Human infections account for ~25% of cases of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in Asia.[12]

R. norvegicus rodents are found in urban areas worldwide, meaning that SEOV and HFRS are also found globally in human populations in urban areas.[3] As of 2015 the virus has been found in wild rats in the Netherlands, and in both rodents and humans in England, Wales, France, Belgium, and Sweden.[1] Rats in New York City are also known reservoirs.[13]

An outbreak of Seoul virus infected eleven people in the U.S. states of Illinois, Indiana and Wisconsin from December 2016 to February 2017. Individuals who operated a home-based rat-breeding facility in Wisconsin became ill and were hospitalized. The ill individuals had purchased rats from animal suppliers in Wisconsin and Illinois. Investigators traced the infection to two Illinois ratteries and identified six additional people who tested positive for Seoul virus. All these individuals recovered. Further investigation by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention revealed that potentially infected rodents may have traveled to the states of Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, North Dakota, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, and Wisconsin.[14][5] Cases were also reported in Ontario in February 2016.[15] In 2017, the investigation further showed that there were 17 infected people and 31 infected ratteries in 11 states, which are Colorado, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, and Wisconsin. The infected rodents are found to be distributed from Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Idaho, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, and Wisconsin.[16]

Although rodents are known to be the main reservoir for the virus, there are studies that show that other wild animals such as cats, dogs, pigs, cattle, and deer can also work as a reservoir. The transmission between the rodents to listed animals also seems to be possible.[17]

Transmission

The SEOV is transmitted to humans mainly from feces, body fluid, and excrete of rodents. It usually occurs in agricultural locations, but there were cases of the virus in the city. It may happen in laboratory environments as well. There are increase in the number of patients in late fall (October to November) and late spring (May to June). The main targeted age group is people in their 20s to 60s, as they are more active than the age group outside of the range.[18]

SEOV in Rodents

Seoul virus is known to be found primarily in Rattus norvegicus (Norway Rat), but has also been seen in Rattus rattus (Black Rat) populations.[3] Traditionally, it has been thought that each virus in the hantavirus genus is highly specific to a single rodent host species,[19][20] but this idea is being challenged.[21][22]

Rattus species rodents do not show symptoms of infection with SEOV.[23]

Disease

Clinical features

In humans, Seoul virus causes hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS), along with other Old World hantaviruses. Although New World hantaviruses typically cause hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS), either disease can involve the patient's kidneys or lungs.[24][25] The virus can cause severe health issues and even death. HPS has a mortality rate of 38%.[26] The infection of the virus in humans can be tested through blood testing as the strain of the virus can be isolated.[27]

The patient will develop high grade fever, sweating, chills, abdominal pain, joint pain, red eye, nausea, vomiting, one or multiple rash(es) and/or a headache as early symptoms. After 4 to 10 days of initial symptoms, the patient may show late symptoms such as coughing and shortness of breath due to the lungs being filled up by liquid.[26]

The incubation period varies from 1–8 weeks. The symptoms can appear quickly, the majority of patients developing symptoms 1–2 weeks from the time of infection. The patient will develop severe symptoms which may lead to death. To prevent contracting this virus, avoid contact with wild rats and only adopt pet rats from trusted sources who have tested their rats by serology in order to confirm their colony does not carry this virus.

Prevention

The best way to prevent the transmission of the virus is to limit the human-rodent interaction.[28]

Treatment

The treatment of HPS has been developed and is proved to be effective, as it shortens the course of illness and reduces the mortality rate. The vaccination of the virus has also been out in the market for over two decades, but the effectiveness has not been clearly supported.[29]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Goeijenbier M; et al. (May 2015). "Seoul hantavirus in brown rats in the Netherlands: implications for physicians—Epidemiology, clinical aspects, treatment and diagnostics". Neth. J. Med. 73 (4): 155–60. PMID 25968286.

- ↑ US Centers for Disease Control. Virology, Hantaviruses Archived 2017-11-23 at the Wayback Machine Page last reviewed: August 29, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Jonsson, Colleen B.; Figueiredo, Luiz Tadeu Moraes; Vapalahti, Olli (2010-04-01). "A Global Perspective on Hantavirus Ecology, Epidemiology, and Disease". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 23 (2): 412–441. doi:10.1128/CMR.00062-09. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 2863364. PMID 20375360.

- ↑ 송기준; 윤형선; 고은영; 정기모; 박광숙; 이용주; 송진원; 백락주 (March 2000). "흰넓적다리붉은쥐 유래 한타바이러스 분리 및 분자생물학적 특성 비교". Journal of Bacteriology and Virology (in 한국어). 30 (1): 19–28. ISSN 1598-2467. Archived from the original on 2022-12-04. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- 1 2 3 US Centers for Disease Control. Multi-state Outbreak of Seoul Virus Archived 2020-11-15 at the Wayback Machine Updated January 19, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Knipe, David M. (2015). Fields Virology. Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 978-1-4511-0563-6. OCLC 956639500.

- ↑ Mir, M. A.; Brown, B.; Hjelle, B.; Duran, W. A.; Panganiban, A. T. (2006-11-01). "Hantavirus N Protein Exhibits Genus-Specific Recognition of the Viral RNA Panhandle". Journal of Virology. 80 (22): 11283–11292. doi:10.1128/JVI.00820-06. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 1642145. PMID 16971445.

- 1 2 Cifuentes-Muñoz, Nicolás; Salazar-Quiroz, Natalia; Tischler, Nicole (2014-04-21). "Hantavirus Gn and Gc Envelope Glycoproteins: Key Structural Units for Virus Cell Entry and Virus Assembly". Viruses. 6 (4): 1801–1822. doi:10.3390/v6041801. ISSN 1999-4915. PMC 4014721. PMID 24755564.

- ↑ Acuna, R.; Cifuentes-Munoz, N.; Marquez, C. L.; Bulling, M.; Klingstrom, J.; Mancini, R.; Lozach, P.-Y.; Tischler, N. D. (2013-12-11). "Hantavirus Gn and Gc Glycoproteins Self-Assemble into Virus-Like Particles". Journal of Virology. 88 (4): 2344–2348. doi:10.1128/jvi.03118-13. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 3911568. PMID 24335294.

- ↑ Krautkramer, E.; Zeier, M. (2008-02-27). "Hantavirus Causing Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome Enters from the Apical Surface and Requires Decay-Accelerating Factor (DAF/CD55)". Journal of Virology. 82 (9): 4257–4264. doi:10.1128/jvi.02210-07. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 2293039. PMID 18305044.

- ↑ Nielsen, Carrie F.; Sethi, Vishal; Petroll, Andrew E.; Kazmierczak, James; Erickson, Bobbie R.; Nichol, Stuart T.; Rollin, Pierre E.; Davis, Jeffrey P. (2010-12-06). "Seoul Virus Infection in a Wisconsin Patient with Recent Travel to China, March 2009: First Documented Case in the Midwestern United States". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 83 (6): 1266–1268. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0424. ISSN 0002-9637. PMC 2990043. PMID 21118933.

- ↑ Yao LS, Qin CF, Pu Y, Zhang XL, Liu YX, Liu Y, Cao XM, Deng YQ, Wang J, Hu KX, Xu BL (2012). "Complete genome sequence of Seoul virus isolated from Rattus norvegicus in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea". J. Virol. 86 (24): 13853. doi:10.1128/JVI.02668-12. PMC 3503101. PMID 23166256.

- ↑ Firth, C (2014). "Detection of Zoonotic Pathogens and Characterization of Novel Viruses Carried by Commensal Rattus norvegicus in New York City". mBio. 5 (5): e01933–14. doi:10.1128/mBio.01933-14. PMC 4205793. PMID 25316698.

- ↑ "Multi-state Outbreak of Seoul Virus | Hantavirus | DHCPP | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-11-15. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- ↑ "3 people in Ontario contract Seoul virus spread by rats". CBC News. The Canadian Press. 1 March 2017. Archived from the original on 4 March 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ↑ "Multi-state Outbreak of Seoul Virus | Hantavirus | DHCPP | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-02-22. Archived from the original on 2020-11-15. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ↑ Zeier, Martin; Handermann, Michaela; Bahr, Udo; Rensch, Baldur; Müller, Sandra; Kehm, Roland; Muranyi, Walter; Darai, Gholamreza (March 2005). "New ecological aspects of hantavirus infection: a change of a paradigm and a challenge of prevention--a review". Virus Genes. 30 (2): 157–180. doi:10.1007/s11262-004-5625-2. ISSN 0920-8569. PMID 15744574. S2CID 30527384. Archived from the original on 2022-12-04. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ↑ 유정희; 남재환; 최택균; 주영란; 이찬희; 신영학; 박근용 (June 2004). "대장균에서 발현된 한타바이러스 N Protein의 응용". Journal of Bacteriology and Virology (in 한국어). 34 (2): 147–155. ISSN 1598-2467. Archived from the original on 2022-12-04. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ↑ Mills, James N. (February 2006). "Biodiversity loss and emerging infectious disease: An example from the rodent-borne hemorrhagic fevers". Biodiversity. 7 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1080/14888386.2006.9712789. ISSN 1488-8386. S2CID 85306868.

- ↑ Plyusnin, A.; Morzunov, S. P. (2001), Schmaljohn, Connie S.; Nichol, Stuart T. (eds.), "Virus Evolution and Genetic Diversity of Hantaviruses and Their Rodent Hosts", Hantaviruses, Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology, Springer, vol. 256, pp. 47–75, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-56753-7_4, ISBN 978-3-642-56753-7, PMID 11217406

- ↑ Chin, Chuan; Chiueh, Tzong-Shi; Yang, Wen-Chin; Yang, Tzong-Horng; Shih, Chwen-Ming; Lin, Hui-Tsu; Lin, Kih-Ching; Lien, Jih-Ching; Tsai, Theodore F.; Ruo, Suyu L.; Nichol, Stuart T. (2000). "Hantavirus infection in Taiwan: The experience of a geographically unique area". Journal of Medical Virology. 60 (2): 237–247. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(200002)60:2<237::AID-JMV21>3.0.CO;2-B. ISSN 1096-9071. PMID 10596027. S2CID 22903467. Archived from the original on 2023-04-13. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ↑ Reusken, Chantal; Heyman, Paul (2013-02-01). "Factors driving hantavirus emergence in Europe". Current Opinion in Virology. Virus entry / Environmental virology. 3 (1): 92–99. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2013.01.002. ISSN 1879-6257. PMID 23384818.

- ↑ Kariwa, H.; Fujiki, M.; Yoshimatsu, K.; Arikawa, J.; Takashima, I.; Hashimoto, N. (February 1998). "Urine-associated horizontal transmission of Seoul virus among rats". Archives of Virology. 143 (2): 365–374. doi:10.1007/s007050050292. ISSN 0304-8608. PMID 9541619. S2CID 32993360.

- ↑ Clement, Jan; Maes, Piet; Van Ranst, Marc (2014-07-17). "Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome in the New, and Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome in the old world: Paradi(se)gm lost or regained?". Virus Research. Hantaviruses. 187: 55–58. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2013.12.036. ISSN 0168-1702. PMID 24440318.

- ↑ Krüger, Detlev H.; Schönrich, Günther; Klempa, Boris (2011-06-01). "Human pathogenic hantaviruses and prevention of infection". Human Vaccines. 7 (6): 685–693. doi:10.4161/hv.7.6.15197. ISSN 1554-8600. PMC 3219076. PMID 21508676.

- 1 2 "Signs & Symptoms | Hantavirus | DHCPP | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-02-22. Archived from the original on 2021-03-20. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ↑ 주용규; 이호왕 (June 1997). "한타바이러스 호왕균주의 M , S 유전자 절편의 염기서열 및 분자생물학적 특성". Journal of Bacteriology and Virology (in 한국어). 27 (1): 59–68. ISSN 1598-2467. Archived from the original on 2022-12-04. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ↑ Nielsen, Carrie F.; Sethi, Vishal; Petroll, Andrew E.; Kazmierczak, James; Erickson, Bobbie R.; Nichol, Stuart T.; Rollin, Pierre E.; Davis, Jeffrey P. (2010-12-06). "Seoul Virus Infection in a Wisconsin Patient with Recent Travel to China, March 2009: First Documented Case in the Midwestern United States". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 83 (6): 1266–1268. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0424. ISSN 0002-9637. PMC 2990043. PMID 21118933.

- ↑ Kim, Hyo Youl (2009). "Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome". Infection and Chemotherapy. 41 (6): 323. doi:10.3947/ic.2009.41.6.323. ISSN 1598-8112. Archived from the original on 2023-04-13. Retrieved 2023-01-13.