Slipped capital femoral epiphysis

| Slipped capital femoral epiphysis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Slipped upper femoral epiphysis (SUFE), coxa vara adolescentium, skiffy, souffy | |

| |

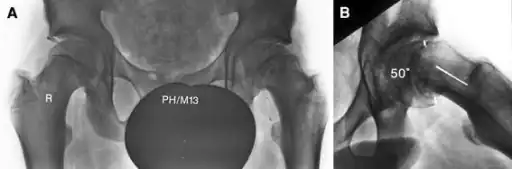

| X-ray showing a slipped capital femoral epiphysis, before and after surgical fixation. | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Groin, hip, knee, or thigh pain, limp[1] |

| Usual onset | 8 to 15 years old[1] |

| Types | Stable, unstable[1] |

| Risk factors | Obesity, hypothyroidism, hypogonadism[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Hip X-rays[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Adductor muscle strain (groin pull), transient synovitis, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, septic arthritis, avulsion fracture[1] |

| Treatment | No weight on affected leg, surgery[1] |

| Frequency | 1 per 10,000 children[1] |

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), also known as a skiffy, is a fracture through the growth plate, which results in slippage of the underlying femoral neck.[1] Symptoms generally include a limp and pain in the groin, hip, thigh, or knee.[1] Ability to fully move the affected hip may also be decreased.[2] Both sides may be affected in 20% to 50% of cases.[1] Complications may include avascular necrosis, chondrolysis, and femoroacetabular impingement.[1]

Risk factors include obesity, hypothyroidism, and hypogonadism.[1] Diagnosis is by Xraying both hips.[1] They are divided into two types: stable and unstable.[1] It is mild if the slip is less than a third, moderate if between a third and a half, and severe if greater than a half.[1] If the diagnosis is delayed a worse outcome may result.[1]

Treatment is generally by surgery.[1] Until this can be carried out the person should put not weight on that leg.[1] SCFE affects 11 per 100,000 children and in adolescents is the most common hip disorder.[1] It generally occurs in those 8 to 15 years old and is more common in males.[1] With rising rates of obesity in children the disease is becoming more common.[2] The condition has been described since at least 1572.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Usually, a SCFE causes groin pain, but it may cause pain in only the thigh or knee, because the pain may be referred along the distribution of the obturator nerve.[4] The pain may occur on both sides of the body (bilaterally), as up to 40 percent of cases involve slippage on both sides.[5] In cases of bilateral SCFEs, they typically occur within one year of each other.[6] About 20 percent of all cases include a SCFE on both sides at the time of presentation.[7]

Signs of a SCFE include a waddling gait, decreased range of motion. Often the range of motion in the hip is restricted in internal rotation, abduction, and flexion.[4] A person with a SCFE may prefer to hold their hip in flexion and external rotation.

Complications

Failure to treat a SCFE may lead to: death of bone tissue in the femoral head (avascular necrosis), degenerative hip disease (hip osteoarthritis),[8] gait abnormalities and chronic pain. SCFE is associated with a greater risk of arthritis of the hip joint later in life.[8] 17–47 percent of acute cases of SCFE lead to the death of bone tissue (osteonecrosis) effects.[4]

Cause

In general, SCFE is caused by increased force applied across the epiphysis, or a decrease in the resistance within the physis to shearing.[6] Obesity is the by far the most significant risk factor. A study in Scotland looked at the weight of 600,000 infants, and followed them up to see who got SCFE.[9] This study identified that obese children had an almost twenty times greater risk than thin children, with a 'dose-response'- so the greater the weight of the child, the greater the risk of SCFE. In 65 percent of cases of SCFE, the person is over the 95th percentile for weight.[4] Endocrine diseases may also contribute (though are far less of a risk than obesity), such as hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism, and renal osteodystrophy.[4][10]

Sometimes no single cause accounts for SCFE, and several factors play a role in the development of a SCFE i.e. both mechanical and endocrine (hormone-related) factors. Skeletal changes may also make someone at risk of SCFE, including femoral or acetabular retroversion,[6] those these may simply be chronic skeletal manifestations of childhood obesity.

Pathophysiology

SCFE is a Salter-Harris type 1 fracture through the proximal femoral physis. Stress around the hip causes a shear force to be applied at the growth plate. While trauma has a role in the manifestation of the fracture, an intrinsic weakness in the physeal cartilage also is present. The almost exclusive incidence of SCFE during the adolescent growth spurt indicates a hormonal role. Obesity is another key predisposing factor in the development of SCFE.

The fracture occurs at the hypertrophic zone of the physeal cartilage. Stress on the hip causes the epiphysis to move posteriorly and medially. By convention, position and alignment in SCFE is described by referring to the relationship of the proximal fragment (capital femoral epiphysis) to the normal distal fragment (femoral neck). Because the physis has yet to close, the blood supply to the epiphysis still should be derived from the femoral neck; however, this late in childhood, the supply is tenuous and frequently lost after the fracture occurs. Manipulation of the fracture frequently results in osteonecrosis and the acute loss of articular cartilage (chondrolysis) because of the tenuous nature of the blood supply.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is a combination of clinical suspicion plus radiological investigation. Children with a SCFE experience a decrease in their range of motion, and are often unable to complete hip flexion or fully rotate the hip inward.[11] 20–50% of SCFE are missed or misdiagnosed on their first presentation to a medical facility. SCFEs may be initially overlooked, because the first symptom is knee pain, referred from the hip. The knee is investigated and found to be normal.[10]

The diagnosis requires x-rays of the pelvis, with anteriorposterior (AP) and frog-leg lateral views.[12] The appearance of the head of the femur in relation to the shaft likens that of a "melting ice cream cone", visible with Klein's line. The severity of the disease can be measured using the Southwick angle.

Drehmann sign – may also be present in SCFE.

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis before surgery

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis before surgery Xray showing SCFE

Xray showing SCFE

Classification

Differential

- Legg–Calvé–Perthes syndrome – another cause of avascular necrosis of the femoral head, seen in younger children than SCFE

- Hip dysplasia

Treatment

The disease can be treated with external in-situ pinning or open reduction and pinning. Consultation with an orthopaedic surgeon is necessary to repair this problem. Pinning the unaffected side prophylactically is not recommended for most patients, but may be appropriate if a second SCFE is very likely.[12]

Once SCFE is suspected, the patient should be non-weight bearing and remain on strict bed rest. In severe cases, after enough rest the patient may require physical therapy to regain strength and movement back to the leg. A SCFE is an orthopaedic emergency, as further slippage may result in occlusion of the blood supply and avascular necrosis (risk of 25 percent). Almost all cases require surgery, which usually involves the placement of one or two pins into the femoral head to prevent further slippage.[13] The recommended screw placement is in the center of the epiphysis and perpendicular to the physis.[14] Chances of a slippage occurring in the other hip are 20 percent within 18 months of diagnosis of the first slippage and consequently the opposite unaffected femur may also require pinning.

The risk of reducing this fracture includes the disruption of the blood supply to the bone. It has been shown in the past that attempts to correct the slippage by moving the head back into its correct position can cause the bone to die. Therefore the head of the femur is usually pinned 'as is'. A small incision is made in the outer side of the upper thigh and metal pins are placed through the femoral neck and into the head of the femur. A dressing covers the wound.

Epidemiology

SCFE affects approximately 1–10 per 100,000 children.[6] The incidence varies by geographic location, season of the year, and ethnicity.[6] In eastern Japan, the incidence is 0.2 per 100,000 and in the northeastern U.S. it is about 10 per 100,000.[4] Africans and Polynesians have higher rates of SCFE.[4]

SCFEs are most common in adolescents 11–15 years of age,[8] and affects boys more frequently than girls (male 2:1 female).[4][6] It is strongly linked to obesity, and weight loss may decrease the risk.[15] Other risk factors include: family history, endocrine disorders, radiation / chemotherapy, and mild trauma.

The left hip is more often affected than the right.[4] Over half of cases may have involvement on both sides (bilateral).[4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Peck, DM; Voss, LM; Voss, TT (15 June 2017). "Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis: Diagnosis and Management". American family physician. 95 (12): 779–784. PMID 28671425.

- 1 2 Karkenny, AJ; Tauberg, BM; Otsuka, NY (September 2018). "Pediatric Hip Disorders: Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis and Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease". Pediatrics in review. 39 (9): 454–463. doi:10.1542/pir.2017-0197. PMID 30171056.

- ↑ Shapiro, Frederic (2002). Pediatric Orthopedic Deformities. Elsevier. p. 379. ISBN 978-0-08-053856-3. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2020-10-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Kliegman, Robert M. (2011). Nelson textbook of pediatrics (19th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. p. 2363. ISBN 9781437707557.

- ↑ Loder, RT (1 May 1998). "Slipped capital femoral epiphysis". American Family Physician. 57 (9): 2135–42, 2148–50. PMID 9606305. Archived from the original on 9 April 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Novais, Eduardo N.; Millis, Michael B. (December 2012). "Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis: Prevalence, Pathogenesis, and Natural History". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 470 (12): 3432–3438. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2452-y. PMC 3492592. PMID 23054509.

- ↑ Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis at eMedicine

- 1 2 3 Kaneshiro, Neil. "Slipped capital femoral epiphysis". U.S. National Library of Medicine. PubMed Health. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ↑ Perry, Daniel C.; Metcalfe, David; Lane, Steven; Turner, Steven (2018). "Childhood Obesity and Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis". Pediatrics. 142 (5): e20181067. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-1067. PMID 30348751.

- 1 2 Perry, Daniel C.; Metcalfe, David; Costa, Matthew L.; Van Staa, Tjeerd (2017). "A nationwide cohort study of slipped capital femoral epiphysis". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 102 (12): 1132–1136. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2016-312328. PMC 5754864. PMID 28663349.

- ↑ Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America. "Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis". American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Archived from the original on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 Peck, David (Aug 1, 2010). "Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: diagnosis and management". American Family Physician. 82 (3): 258–62. PMID 20672790. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ↑ Kuzyk, Paul R.; Kim, YJ; Millis, MB (Nov 2011). "Surgical management of healed slipped capital femoral epiphysis". The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 19 (11): 667–77. doi:10.5435/00124635-201111000-00003. PMID 22052643. S2CID 38580394. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ↑ Merz, Michael K.; Amirouche, Farid; Solitro, Giovanni F.; Silverstein, Jeffrey A.; Surma, Tyler; Gourineni, Prasad V. (2014). "Biomechanical Comparison of Perpendicular Versus Oblique in Situ Screw Fixation of Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis". Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 35 (8): 816–20. doi:10.1097/BPO.0000000000000379. PMID 25526584. S2CID 11578375.

- ↑ "Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis". U.S. National Library of Medicine. National Institute of Health. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |