Southern blot

A Southern blot is a method used in molecular biology for detection of a specific DNA sequence in DNA samples. Southern blotting combines transfer of electrophoresis-separated DNA fragments to a filter membrane and subsequent fragment detection by probe hybridization.[1][2]

The method is named after the British biologist Edwin Southern, who first published it in 1975.[3] Other blotting methods (i.e., western blot,[4] northern blot, eastern blot, southwestern blot) that employ similar principles, but using RNA or protein, have later been named in reference to Edwin Southern's name. As the label is eponymous, Southern is capitalised, as is conventional of proper nouns. The names for other blotting methods may follow this convention, by analogy.[5]

Method

The folowing is the method via which a Southern blot is conducted:[6][7][8][9]

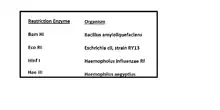

1.Restriction endonucleases are used to cut high-molecular-weight DNA strands into smaller fragments.

2.The DNA fragments are then electrophoresed on an agarose gel to separate them by size (if some of the DNA fragments are larger than 15 kb, then prior to blotting, the gel may be treated with an acid, such as dilute HCl. This depurinates the DNA fragments, breaking the DNA into smaller piece)

3. If alkaline transfer methods are used, the DNA gel is placed into an alkaline solution, sodium hydroxide, to denature the double-stranded DNA. The denaturation in an alkaline environment may improve binding of the negatively charged thymine residues of DNA to a positively charged amino groups of membrane, separating it into single DNA strands for later hybridization to the probe , and destroys any residual RNA that may still be present in the DNA. The choice of alkaline over neutral transfer methods, however, is often empirical and may result in equivalent results.

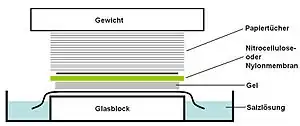

4. A sheet of nitrocellulose membrane is placed on top of or below, (depending on direction of transfer) the gel. Pressure is applied evenly to the gel (either using suction, or by placing a stack of paper towels and a weight on top of membrane and gel), to ensure good and even contact between gel and membrane. If transferring by suction, 20X SSC buffer is used to ensure a seal and prevent drying of the gel. Buffer transfer by capillary action from a region of high water potential to a region of low water potential (usually filter paper/paper tissues) is then used to move the DNA from the gel onto the membrane; ion exchange interactions bind the DNA to the membrane due to the negative charge of the DNA and positive charge of the membrane.

5. The membrane is then baked in a vacuum or regular oven at 80 °C for 2 hours (standard conditions; nitrocellulose or nylon membrane) or exposed to ultraviolet radiation (nylon membrane) to permanently attach the transferred DNA to the membrane.

6. The membrane is then exposed to a hybridization probe—a single DNA fragment with a specific sequence whose presence in the target DNA is to be determined. The probe DNA is labelled so that it can be detected, usually by incorporating radioactivity or tagging the molecule with a fluorescent or chromogenic dye. In some cases, the hybridization probe may be made from RNA, rather than DNA. To ensure the specificity of the binding of the probe to the sample DNA, most common hybridization methods use salmon or herring sperm DNA for blocking of the membrane surface and target DNA, deionized formamide, and detergents such as SDS to reduce non-specific binding of the probe.

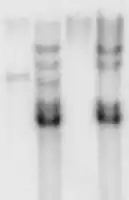

7. After hybridization, excess probe is washed from the membrane (using SSC buffer), and the pattern of hybridization is visualized on X-ray film by autoradiography in the case of a radioactive or fluorescent probe, or by development of colour on the membrane if a chromogenic detection method is used.

Southern blot autoradiography

Southern blot autoradiography.jpg.webp) Agarose gel

Agarose gel Tray with a stack consisting top down of a weight, paper towels, membrane of nitrocellulose or nylon, gel, salt solution and a slab of glass.

Tray with a stack consisting top down of a weight, paper towels, membrane of nitrocellulose or nylon, gel, salt solution and a slab of glass.

Result

Hybridization of the probe to a specific DNA fragment on the filter membrane indicates that this fragment contains DNA sequence that is complementary to the probe. The transfer step of the DNA from the electrophoresis gel to a membrane permits easy binding of the labeled hybridization probe to the size-fractionated DNA; it also allows for the fixation of the target-probe hybrids, required for analysis by autoradiography Southern blots performed with restriction enzyme-digested genomic DNA may be used to determine the number of sequences in a genome. A probe that hybridizes only to a single DNA segment that has not been cut by the restriction enzyme will produce a single band on a Southern blot, whereas multiple bands will likely be observed when the probe hybridizes to several highly similar sequences. Modification of the hybridization conditions may be used to increase specificity and decrease hybridization of the probe to sequences that are less than 100% similar.[10][11][12]

Applications

Southern blotting transfer may be used for homology-based cloning on the basis of amino acid sequence of the protein product of the target gene. Oligonucleotides are designed so that they are similar to the target sequence. The oligonucleotides are chemically synthesized, radiolabeled, and used to screen a DNA library, or other collections of cloned DNA fragments. Sequences that hybridize with the hybridization probe are further analysed, to obtain the full length sequence of the targeted gene.[13][14][15]

Southern blotting can also be used to identify methylated sites in particular genes. Particularly useful are the restriction nucleases MspI and HpaII, both of which recognize and cleave within the same sequence. However, HpaII requires that a C within that site be methylated, whereas MspI cleaves only DNA unmethylated at that site. Therefore, any methylated sites within a sequence analyzed with a particular probe will be cleaved by the former, but not the latter, enzyme.[16]

See also

- Gel electrophoresis of nucleic acids

- Restriction fragment

- Genetic fingerprint

- Northern blot

- Western blot

- Eastern blot

- Southwestern blot

- Northwestern blot

- Far-eastern blot

References

- ↑ "Southern Blot". Archived from the original on 2021-10-11. Retrieved 2021-10-15.

- ↑ Gooch, Jan W. (2011). "Southern Blotting". Encyclopedic Dictionary of Polymers. Springer. pp. 924–924. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-6247-8_14827. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ↑ Southern, Edwin Mellor (5 November 1975). "Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis". Journal of Molecular Biology. 98 (3): 503–517. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(75)80083-0. ISSN 0022-2836. PMID 1195397.

- ↑ Towbin; Staehelin, T; Gordon, J; et al. (1979). "Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications". PNAS. 76 (9): 4350–4. Bibcode:1979PNAS...76.4350T. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. PMC 411572. PMID 388439.

- ↑ Burnette, W. Neal (April 1981). "Western Blotting: Electrophoretic Transfer of Proteins from Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gels to Unmodified Nitrocellulose and Radiographic Detection with Antibody and Radioiodinated Protein A". Analytical Biochemistry. 112 (2): 195–203. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(81)90281-5. ISSN 0003-2697. PMID 6266278.

- ↑ "Protocol Online: Cached". www.protocol-online.org. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ↑ McMahon, Kelly; Paciorkowski, Alex R.; Walters-Sen, Lauren C.; Milunsky, Jeff M.; Bassuk, Alexander; Darbro, Benjamin; Diaz, Jullianne; Dobyns, William B.; Gropman, Andrea (1 January 2017). "34 - Neurogenetics in the Genome Era". Swaiman's Pediatric Neurology (Sixth Edition). Elsevier. pp. 257–267. ISBN 978-0-323-37101-8. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ↑ Brown, T. (May 2001). "Southern blotting". Current Protocols in Immunology. Chapter 10: Unit 10.6A. doi:10.1002/0471142735.im1006as06. ISSN 1934-368X. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ↑ Southern, Ed (2006). "Southern blotting". Nature Protocols. 1 (2): 518–525. doi:10.1038/nprot.2006.73. ISSN 1750-2799. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ↑ Gebbie, Leigh (2014). "Genomic Southern Blot Analysis". Cereal Genomics: Methods and Protocols. Humana Press. pp. 159–177. ISBN 978-1-62703-715-0. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ↑ Green, Michael R.; Sambrook, Joseph (1 December 2020). "Autoradiography and Phosphorimaging". Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2020 (12). doi:10.1101/pdb.top100446. ISSN 1559-6095. Archived from the original on 2 February 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ↑ Croning, Mike DR; Fricker, David G.; Komiyama, Noboru H.; Grant, Seth GN (29 January 2010). "Automated design of genomic Southern blot probes". BMC Genomics. 11 (1): 74. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-74. ISSN 1471-2164. Archived from the original on 2021-04-19. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ↑ Polyak, Kornelia; Meyerson, Matthew (2003). Gene Analysis: DNA. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ↑ MacNeil, Douglas J.; Weinberg, David H. (2000). "Homology-Based Cloning Methods". Neuropeptide Y Protocols. Humana Press. pp. 61–70. ISBN 978-1-59259-042-1. Archived from the original on 1 June 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ↑ Herzyk, Pawel (1 January 2014). "Chapter 8 - Next-Generation Sequencing". Handbook of Pharmacogenomics and Stratified Medicine. Academic Press. pp. 125–145. ISBN 978-0-12-386882-4. Archived from the original on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ↑ Biochemistry 3rd Edition, Matthews, Van Holde et al, Addison Wesley Publishing, pg 977

External links

| Library resources about Southern blot |

- OpenWetWare Archived 2021-12-15 at the Wayback Machine