Scapula

| Scapula | |

|---|---|

| |

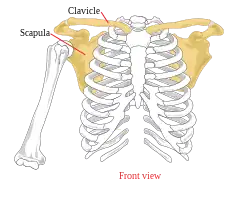

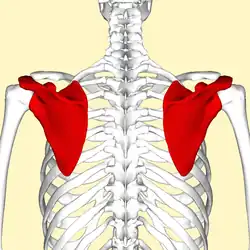

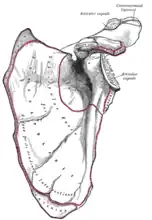

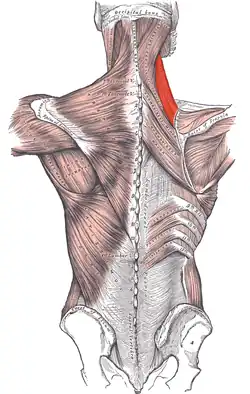

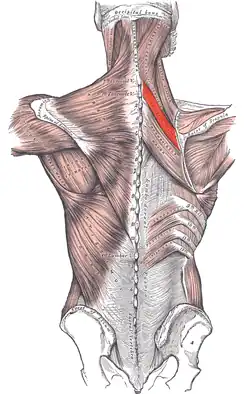

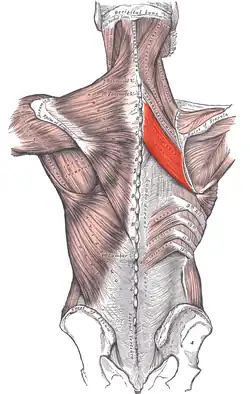

The upper picture is an anterior (from the front) view of the thorax and shoulder girdle. The lower picture is a posterior (from the rear) view of the thorax (scapula shown in red.) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Scapula (omo) |

| MeSH | D012540 |

| TA98 | A02.4.01.001 |

| TA2 | 1143 |

| FMA | 13394 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

In anatomy, the scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas[1]), also known as the shoulder bone, shoulder blade, wing bone, speal bone or blade bone, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on either side of the body being roughly a mirror image of the other. The name derives from the Classical Latin word for trowel or small shovel, which it was thought to resemble.

In compound terms, the prefix omo- is used for the shoulder blade in medical terminology. This prefix is derived from ὦμος (ōmos), the Ancient Greek word for shoulder, and is cognate with the Latin (h)umerus, which in Latin signifies either the shoulder or the upper arm bone.

The scapula forms the back of the shoulder girdle. In humans, it is a flat bone, roughly triangular in shape, placed on a posterolateral aspect of the thoracic cage.[2]

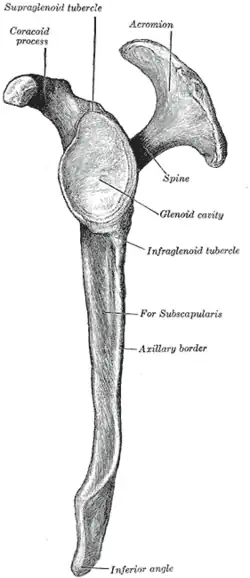

Structure

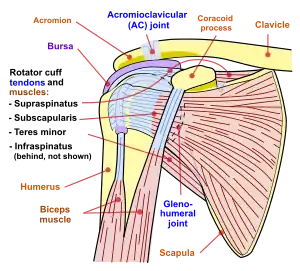

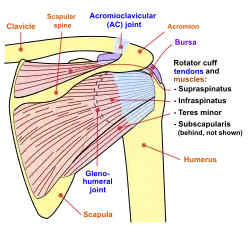

The scapula is a thick, flat bone lying on the thoracic wall that provides an attachment for three groups of muscles: intrinsic, extrinsic, and stabilizing and rotating muscles. The intrinsic muscles of the scapula include the muscles of the rotator cuff—the subscapularis, teres minor, supraspinatus, and infraspinatus.[3] These muscles attach to the surface of the scapula and are responsible for the internal and external rotation of the shoulder joint, along with humeral abduction.

The extrinsic muscles include the biceps, triceps, and deltoid muscles and attach to the coracoid process and supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula, infraglenoid tubercle of the scapula, and spine of the scapula. These muscles are responsible for several actions of the glenohumeral joint.

The third group, which is mainly responsible for stabilization and rotation of the scapula, consists of the trapezius, serratus anterior, levator scapulae, and rhomboid muscles. These attach to the medial, superior, and inferior borders of the scapula.

The head, processes, and the thickened parts of the bone contain cancellous tissue; the rest consists of a thin layer of compact tissue.

The central part of the supraspinatus fossa and the upper part of the infraspinatous fossa, but especially the former, are usually so thin in humans as to be semitransparent; occasionally the bone is found wanting in this situation, and the adjacent muscles are separated only by fibrous tissue. The scapula has two surfaces, three borders, three angles, and three processes.

Surfaces

- Front or subscapular fossa

The front of the scapula (also known as the costal or ventral surface) has a broad concavity called the subscapular fossa, to which the subscapularis muscle attaches. The medial two-thirds of the fossa have 3 longitudinal oblique ridges, and another thick ridge adjoins the lateral border; they run outward and upward. The ridges give attachment to the tendinous insertions, and the surfaces between them to the fleshy fibers, of the subscapularis muscle. The lateral third of the fossa is smooth and covered by the fibers of this muscle.

At the upper part of the fossa is a transverse depression, where the bone appears to be bent on itself along a line at right angles to and passing through the center of the glenoid cavity, forming a considerable angle, called the subscapular angle; this gives greater strength to the body of the bone by its arched form, while the summit of the arch serves to support the spine and acromion.

The costal surface superior of the scapula is the origin of 1st digitation for the serratus anterior origin.

|

|

|

- Back

The back of the scapula (also called the dorsal or posterior surface) is arched from above downward, and is subdivided into two unequal parts by the spine of the scapula. The portion above the spine is called the supraspinous fossa, and that below it the infraspinous fossa. The two fossae are connected by the spinoglenoid notch, situated lateral to the root of the spine.

- The supraspinous fossa, above the spine of scapula, is concave, smooth, and broader at its vertebral than at its humeral end; its medial two-thirds give origin to the Supraspinatus. At its lateral surface resides the spinoglenoid fossa which is situated by the medial margin of the glenoid. The spinoglenoid fossa houses the suprascpular canal which forms a connecting passage between the suprascapular notch and the spinoglenoid notch conveying the suprascapular nerve and vessels.[4]

- The infraspinous fossa is much larger than the preceding; toward its vertebral margin a shallow concavity is seen at its upper part; its center presents a prominent convexity, while near the axillary border is a deep groove which runs from the upper toward the lower part. The medial two-thirds of the fossa give origin to the Infraspinatus; the lateral third is covered by this muscle.

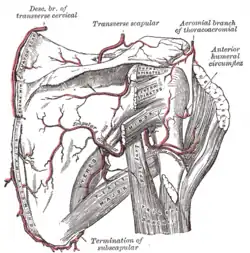

There is a ridge on the outer part of the back of the scapula. This runs from the lower part of the glenoid cavity, downward and backward to the vertebral border, about 2.5 cm above the inferior angle. Attached to the ridge is a fibrous septum, which separates the infraspinatus muscle from the Teres major and Teres minor muscles. The upper two-thirds of the surface between the ridge and the axillary border is narrow, and is crossed near its center by a groove for the scapular circumflex vessels; the Teres minor attaches here.

The broad and narrow portions above alluded to are separated by an oblique line, which runs from the axillary border, downward and backward, to meet the elevated ridge: to it is attached a fibrous septum which separates the Teres muscles from each other.

Its lower third presents a broader, somewhat triangular surface, the inferior angle of the scapula, which gives origin to the Teres major, and over which the Latissimus dorsi glides; frequently the latter muscle takes origin by a few fibers from this part.

|  |  |

- Side

The acromion forms the summit of the shoulder, and is a large, somewhat triangular or oblong process, flattened from behind forward, projecting at first laterally, and then curving forward and upward, so as to overhang the glenoid cavity.

|  |  |

Angles

There are 3 angles:

The superior angle of the scapula or medial angle, is covered by the trapezius muscle. This angle is formed by the junction of the superior and medial borders of the scapula. The superior angle is located at the approximate level of the second thoracic vertebra. The superior angle of the scapula is thin, smooth, rounded, and inclined somewhat lateralward, and gives attachment to a few fibers of the levator scapulae muscle.[5]

The inferior angle of the scapula is the lowest part of the scapula and is covered by the latissimus dorsi muscle. It moves forwards round the chest when the arm is abducted. The inferior angle is formed by the union of the medial and lateral borders of the scapula. It is thick and rough and its posterior or back surface affords attachment to the teres major and often to a few fibers of the latissimus dorsi. The anatomical plane that passes vertically through the inferior angle is named the scapular line.

The lateral angle of the scapula or glenoid angle also known as the head of the scapula is the thickest part of the scapula. It is broad and bears the glenoid cavity on its articular surface which is directed forward, laterally and slightly upwards, and articulates with the head of the humerus. The inferior angle is broader below than above and its vertical diameter is the longest. The surface is covered with cartilage in the fresh state; and its margins, slightly raised, give attachment to a fibrocartilaginous structure, the glenoidal labrum, which deepens the cavity. At its apex is a slight elevation, the supraglenoid tuberosity, to which the long head of the biceps brachii is attached.

The anatomic neck of the scapula is the slightly constricted portion which surrounds the head and is more distinct below and behind than above and in front. The surgical neck of the scapula passes directly medial to the base of the coracoid process.[6]

Superior angle shown in red

Superior angle shown in red Lateral angle shown in red

Lateral angle shown in red Anatomic neck: red, Surgical neck: purple

Anatomic neck: red, Surgical neck: purple Inferior angle shown in red

Inferior angle shown in red

Borders

There are three borders of the scapula:

- The superior border is the shortest and thinnest; it is concave, and extends from the superior angle to the base of the coracoid process. It is referred to as the cranial border in animals.

- At its lateral part is a deep, semicircular notch, the scapular notch, formed partly by the base of the coracoid process. This notch is converted into a foramen by the superior transverse scapular ligament, and serves for the passage of the suprascapular nerve; sometimes the ligament is ossified.

- The adjacent part of the superior border affords attachment to the omohyoideus.

Costal surface of left scapula. Superior border shown in red.

Costal surface of left scapula. Superior border shown in red. Left scapula. Superior border shown in red.

Left scapula. Superior border shown in red. Animation. Superior border shown in red.

Animation. Superior border shown in red.

- The axillary border (or "lateral border") is the thickest of the three. It begins above at the lower margin of the glenoid cavity, and inclines obliquely downward and backward to the inferior angle. It is referred to as the caudal border in animals.

- It begins above at the lower margin of the glenoid cavity, and inclines obliquely downward and backward to the inferior angle.

- Immediately below the glenoid cavity is a rough impression, the infraglenoid tuberosity, about 2.5 cm (1 in). in length, which gives origin to the long head of the triceps brachii; in front of this is a longitudinal groove, which extends as far as the lower third of this border, and affords origin to part of the subscapularis.

- The inferior third is thin and sharp, and serves for the attachment of a few fibers of the teres major behind, and of the subscapularis in front.

Dorsal surface of left scapula. Lateral border shown in red.

Dorsal surface of left scapula. Lateral border shown in red. Left scapula. Lateral border shown in red.

Left scapula. Lateral border shown in red. Animation. Lateral border shown in red.

Animation. Lateral border shown in red.

- The medial border (also called the vertebral border or medial margin) is the longest of the three borders, and extends from the superior angle to the inferior angle.[7] In animals it is referred to as the dorsal border.

- Four muscles attach to the medial border. Serratus anterior has a long attachment on the anterior lip. Three muscles insert along the posterior lip, the levator scapulae (uppermost), rhomboid minor (middle), and to the rhomboid major (lower middle).[7]

Left scapula. Medial border shown in red.

Left scapula. Medial border shown in red. Animation. Medial border shown in red.

Animation. Medial border shown in red. Still image. Medial border shown in red.

Still image. Medial border shown in red. Levator scapulae muscle (red)

Levator scapulae muscle (red) Rhomboid minor muscle (red)

Rhomboid minor muscle (red) Rhomboid major muscle (red)

Rhomboid major muscle (red)

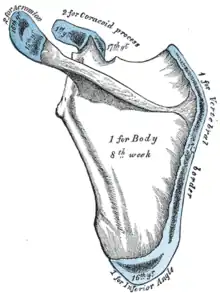

Development

The scapula is ossified from 7 or more centers: one for the body, two for the coracoid process, two for the acromion, one for the vertebral border, and one for the inferior angle. Ossification of the body begins about the second month of fetal life, by an irregular quadrilateral plate of bone forming, immediately behind the glenoid cavity. This plate extends to form the chief part of the bone, the scapular spine growing up from its dorsal surface about the third month. Ossification starts as membranous ossification before birth.[8][9] After birth, the cartilaginous components would undergo endochondral ossification. The larger part of the scapula undergoes membranous ossification.[10] Some of the outer parts of the scapula are cartilaginous at birth, and would therefore undergo endochondral ossification.[11]

At birth, a large part of the scapula is osseous, but the glenoid cavity, the coracoid process, the acromion, the vertebral border and the inferior angle are cartilaginous. From the 15th to the 18th month after birth, ossification takes place in the middle of the coracoid process, which as a rule becomes joined with the rest of the bone about the 15th year.

Between the 14th and 20th years, the remaining parts ossify in quick succession, and usually in the following order: first, in the root of the coracoid process, in the form of a broad scale; secondly, near the base of the acromion; thirdly, in the inferior angle and contiguous part of the vertebral border; fourthly, near the outer end of the acromion; fifthly, in the vertebral border. The base of the acromion is formed by an extension from the spine; the two nuclei of the acromion unite, and then join with the extension from the spine. The upper third of the glenoid cavity is ossified from a separate center (sub coracoid), which appears between the 10th and 11th years and joins between the 16th and the 18th years. Further, an epiphysial plate appears for the lower part of the glenoid cavity, and the tip of the coracoid process frequently has a separate nucleus. These various epiphyses are joined to the bone by the 25th year.

Failure of bony union between the acromion and spine sometimes occurs (see os acromiale), the junction being effected by fibrous tissue, or by an imperfect articulation; in some cases of supposed fracture of the acromion with ligamentous union, it is probable that the detached segment was never united to the rest of the bone.

"In terms of comparative anatomy the human scapula represents two bones that have become fused together; the (dorsal) scapula proper and the (ventral) coracoid. The epiphyseal line across the glenoid cavity is the line of fusion. They are the counterparts of the ilium and ischium of the pelvic girdle."

— R. J. Last – 'Last's Anatomy

Function

The following muscles attach to the scapula:

| Muscle | Direction | Region |

| Pectoralis Minor | insertion | coracoid process |

| Coracobrachialis | origin | coracoid process |

| Serratus Anterior | insertion | medial border |

| Triceps Brachii (long head) | origin | infraglenoid tubercle |

| Biceps Brachii (short head) | origin | coracoid process |

| Biceps Brachii (long head) | origin | supraglenoid tubercle |

| Subscapularis | origin | subscapular fossa |

| Rhomboid Major | insertion | medial border |

| Rhomboid Minor | insertion | medial border |

| Levator Scapulae | insertion | medial border |

| Trapezius | insertion | spine of scapula |

| Deltoid | origin | spine of scapula |

| Supraspinatus | origin | supraspinous fossa |

| Infraspinatus | origin | infraspinous fossa |

| Teres Minor | origin | lateral border |

| Teres Major | origin | lateral border |

| Latissimus Dorsi (a few fibers, attachment may be absent) | origin | inferior angle |

| Omohyoid | origin | superior border |

Movements

Movements of the scapula are brought about by the scapular muscles. The scapula can perform six actions:

- Elevation: upper trapezius and levator scapulae

- Depression: lower trapezius

- Retraction (adduction): rhomboids and middle trapezius

- Protraction (abduction): serratus anterior

- Upward rotation: upper and lower trapezius, serratus anterior

- Downward rotation: rhomboids,[12][13] Levator Scapulae, and Pec Minor

Clinical significance

Scapular fractures

Because of its sturdy structure and protected location, fractures of the scapula are uncommon. When they do occur, they are an indication that severe chest trauma has occurred.[14] Scapular fractures involving the neck of the scapula have two patterns. One (rare) type of fracture is through the anatomical neck of the scapula. The other more common type of fracture is through the surgical neck of the scapula. The surgical neck exits medial to the coracoid process.[15]

An abnormally protruding inferior angle of the scapula is known as a winged scapula and can be caused by paralysis of the serratus anterior muscle. In this condition the sides of the scapula nearest the spine are positioned outward and backward. The appearance of the upper back is said to be wing-like. In addition, any condition causing weakness of the serratus anterior muscle may cause scapular "winging".

Impingement syndrome

The scapula plays an important role in shoulder impingement syndrome.[16]

Abnormal scapular function is called scapular dyskinesis. One action the scapula performs during a throwing or serving motion is elevation of the acromion process in order to avoid impingement of the rotator cuff tendons.[16] If the scapula fails to properly elevate the acromion, impingement may occur during the cocking and acceleration phase of an overhead activity. The two muscles most commonly inhibited during this first part of an overhead motion are the serratus anterior and the lower trapezius.[17] These two muscles act as a force couple within the glenohumeral joint to properly elevate the acromion process, and if a muscle imbalance exists, shoulder impingement may develop.

History

Etymology

Scapula/Scapulae

The name scapula as synonym of shoulder blade is of Latin origin.[18] It is commonly used in medical English[18][19][20] and is part of the current official Latin nomenclature, Terminologia Anatomica.[21]

In classical Latin scapula is only used in its plural scapulae.[22] Although some sources mention that scapulae is used to refer during Roman antiquity to the shoulders [23] or to the shoulder blades,[23] others persist in that the Romans used scapulae only to refer to the back,[22][24] in contrast to the pectus,[22] the Latin name for breast [23] or chest.

Os latum scapularum and related

The Roman encyclopedist Aulus Cornelius Celsus who lived during the beginning of the era, also used scapulae to refer to the back.[22] He used os latum scapularum to refer to the shoulder blade.[22] This expressions can be translated as broad (Latin: latum[23]) bone (Latin: os[23]) of the back (Latin: scapularum[22]).

A similar expression in ancient Greek can be seen in the writings of the Greek philosopher Aristoteles and in the writings of the Greek physician Galen.[22] They both use the name ὠμοπλάτη to refer to the shoulder blade.[22][25] This compound consists of ancient Greek ὦμος, shoulder [25] and πλάτη, blade [25] or flat or broad object.[25] Πλάτη in its plural πλάται without ὦμο- was also used in ancient Greek to refer to the shoulder blades.[25] In anatomic Latin, ὠμοπλάτη is Latinized as omoplata.[26]

The Latin word umerus is related to ὦμος.[25][27] The Romans referred with umerus to what is now commonly known in English as the following 3 bones: humerus or the upper bone of the arm, the clavicle or the collarbone and the scapula or the shoulder blade. The spelling humerus is actually incorrect in classical Latin.[23]

Those three bones were referred to as the ossa (Latin: bones[23]) umeri (Latin: of the umerus). Umerus was also used to refer specifically to the shoulder.[23] This mirrors the use of ὦμος in ancient Greek as that could refer to the shoulder with the upper arm [25] or to the shoulder [25] alone.

Since Celsus, the os umeri could refer specifically to the upper bone of the arm.[22] The 16th century anatomist Andreas Vesalius used humerus to refer to the clavicle.[22] Besides the aforementioned os latum scapularum, Celsus used os latum umeri to refer to the shoulder blade.[22] Similarly, Laurentius used the expression latitudo umeri (Latitudo = breadth, width [25]) to refer to the shoulder blade.[22]

Pala

The Roman physician Caelius Aurelianus (5th century) used pala to refer to the shoulder blade.[22][23] The name pala is normally used to refer to a spade in Latin[22][23][28] and was therefore probably used by Caelius Aurelianus to describe the shoulder blade, as both exhibit a flat curvature.[22]

Spathula/Σπάθη

During the Middle Ages spathula was used to refer to the shoulder blade.[22] Spathula is a diminutive of spatha,[22][23] with the latter originally meaning broad, two-edged sword without a point,[23] broad, flat, wooden instrument for stirring any liquid, a spattle, spatula [23] or spathe of the palm tree [23] and its diminutive used in classical and late Latin for referring to a leg of pork [23] or a little palmbranch.[23]

The English word spatula is actually derived from Latin spatula,[29] an orthographic variant of spathula.[22][23] Oddly enough, classical Latin non-diminutive spatha can be translated as English spatula,[23] while its Latin diminutive spatula is not translated as English spatula.[23]

Latin spatha is derived from ancient Greek σπάθη.[22][23][28] Therefore, the form spathula is more akin to its origin than spatula.[22] Ancient Greek σπάθη has a similar meaning as Latin spatha, as any broad blade,[25] and can also refer to a spatula[25] or to the broad blade of a sword.,[25] but also to the blade of an oar.[25][27] The aforementioned πλάται for shoulder blades was also used for blades of an oar.[27] Concordantly σπάθη was also used to refer to the shoulder blade.[22][30]

The English word spade,[29][31] as well as the Dutch equivalent spade [32][33] is cognate with σπάθη. Please notice, that the aforementioned term pala as applied by Roman physician Caelius Aurelianus, also means spade. Pala is probably related to the Latin verb pandere,[28] to spread out,[28] and to extend.[28] This verb is thought to be derived from an earlier form spandere,[23] with the root spa-.[23] Σπάθη is actually derived from the similar root spē(i),[27] that means to extend.[27]

It seems that os latum scapularum, ὠμοπλάτη, πλάται, pala, spathula and σπάθη all refer to the same aspect of the shoulder blade, i.e. being a flat, broad blade, with the latter three words etymological related to each other.

Scapula after the Middle Ages

After the Middle Ages, the name scapula for shoulder blade became dominant.[22] The word scapula can etymologically be explained by its relatedness to the ancient Greek verb σκάπτειν,[28][29] to dig.[25] This relatedness gives rise to several possible explanations.

First, the noun σκάπετος, trench,[25] and the scapula related noun σκαφη,[26] are both derived from this verb[25][26] and might connect scapula to the notion of concavity.[22] The name scapula then may be related to the concavity of the bone that exists due to its spine. The designation scapulae is additionally seen as synonym of ancient Greek συνωμία,[34] the space between the shoulder blades,[25] that is obviously concave. Συνωμία consists of σύν, together with,[25] and ὦμος, shoulder.[25]

Second, scapula, due to its relatedness to σκάπτειν might have originally meant shovel.[29] Similarly to the Latin use of pala (spade), a resemblance might be felt between the shape of a shovel and the shoulder blade.[29] Alternatively, the shoulder blade might have been used originally for digging and shoveling.[29]

Shoulder blade

Shoulder blade is colloquial name for this bone. Shoulder is cognate to German and Dutch equivalents Schulter and schouder.[29][31] There are a few etymological explanations for shoulder. The first supposes that shoulder can be literally translated as that which shields or protects,[31] as its possibly related to Icelandic skioldr, shield and skyla, to cover, to defend.[31] The second explanation relates shoulder to ancient Greek σκέλος,[33] leg.[25] The latter spots the possible root skel-,[27] meaning to bend, to curve.[27][33] The third explanation links the root skel- to to cleave.[32] This meaning could refer to the shape of the shoulder blade.[33]

In other animals

In fish, the scapular blade is a structure attached to the upper surface of the articulation of the pectoral fin, and is accompanied by a similar coracoid plate on the lower surface. Although sturdy in cartilagenous fish, both plates are generally small in most other fish, and may be partially cartilagenous, or consist of multiple bony elements.[35]

In the early tetrapods, these two structures respectively became the scapula and a bone referred to as the procoracoid (commonly called simply the "coracoid", but not homologous with the mammalian structure of that name). In amphibians and reptiles (birds included), these two bones are distinct, but together form a single structure bearing many of the muscle attachments for the forelimb. In such animals, the scapula is usually a relatively simple plate, lacking the projections and spine that it possesses in mammals. However, the detailed structure of these bones varies considerably in living groups. For example, in frogs, the procoracoid bones may be braced together at the animal's underside to absorb the shock of landing, while in turtles, the combined structure forms a Y-shape in order to allow the scapula to retain a connection to the clavicle (which is part of the shell). In birds, the procoracoids help to brace the wing against the top of the sternum.[35]

In the fossil therapsids, a third bone, the true coracoid, formed just behind the procoracoid. The resulting three-boned structure is still seen in modern monotremes, but in all other living mammals, the procoracoid has disappeared, and the coracoid bone has fused with the scapula, to become the coracoid process. These changes are associated with the upright gait of mammals, compared with the more sprawling limb arrangement of reptiles and amphibians; the muscles formerly attached to the procoracoid are no longer required. The altered musculature is also responsible for the alteration in the shape of the rest of the scapula; the forward margin of the original bone became the spine and acromion, from which the main shelf of the shoulder blade arises as a new structure.[35]

In dinosaurs

In dinosaurs the main bones of the pectoral girdle were the scapula (shoulder blade) and the coracoid, both of which directly articulated with the clavicle. The clavicle was present in saurischian dinosaurs but largely absent in ornithischian dinosaurs. The place on the scapula where it articulated with the humerus (upper bone of the forelimb) is called the glenoid. The scapula serves as the attachment site for a dinosaur's back and forelimb muscles.

Gallery

3D image

3D image Position of scapula (shown in red). Animation.

Position of scapula (shown in red). Animation. Shape of scapula (left). Animation.

Shape of scapula (left). Animation. Thorax seen from behind.

Thorax seen from behind. Diagram of the human shoulder joint, front view

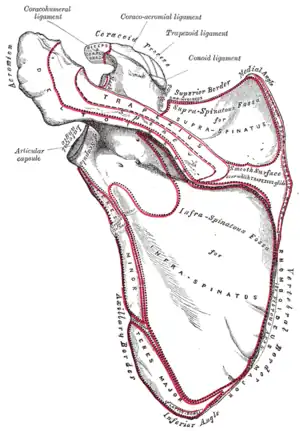

Diagram of the human shoulder joint, front view Diagram of the human shoulder joint, back view

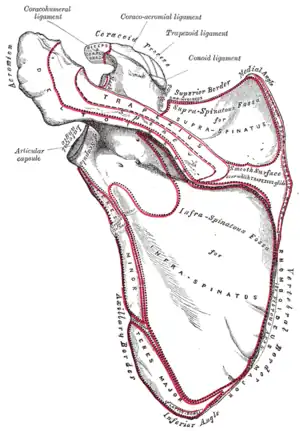

Diagram of the human shoulder joint, back view The scapular and circumflex arteries.

The scapular and circumflex arteries. Left scapula. Dorsal surface. (Superior border labeled at center top.)

Left scapula. Dorsal surface. (Superior border labeled at center top.) Scapula. Medial view.

Scapula. Medial view. Scapula. Anterior face.

Scapula. Anterior face. Scapula. Posterior face.

Scapula. Posterior face. Computer Generated turn around Image of scapula

Computer Generated turn around Image of scapula Suprascapular canal path

Suprascapular canal path- Scapula Anatomy

See also

- Scapulimancy/Oracle bone

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 202 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 202 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ↑ O.D.E. 2nd Ed. 2005

- ↑ "Scapula (Shoulder Blade) Anatomy, Muscles, Location, Function | EHealthStar". www.ehealthstar.com. 2 December 2014. Retrieved 2016-03-17.

- ↑ Marieb, E. (2005). Anatomy & Physiology (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Pearson Benjamin Cummings.

- ↑ Al-Redouan, Azzat; Holding, Keiv; Kachlik, David (2021). ""Suprascapular canal": Anatomical and topographical description and its clinical implication in entrapment syndrome". Annals of Anatomy. 233: 151593. doi:10.1016/j.aanat.2020.151593. PMID 32898658.

- ↑ Gray, Henry (1918). Anatomy of the Human Body, 20th ed. / thoroughly rev. and re-edited by Warren H. Lewis. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger. p. 206. OL 24786057M.

- ↑ Frich, Lars Henrik; Larsen, Morten Schultz (2017). "How to deal with a glenoid fracture". EFORT Open Reviews. 2 (5): 151–157. doi:10.1302/2058-5241.2.160082. ISSN 2396-7544. PMC 5467683. PMID 28630753.

- 1 2 Shuenke, Michael (2010). Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. New York: Everbest Printing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-60406-286-1.

- ↑ "GE Healthcare - Home". www.gehealthcare.com.

- ↑ Thaller, Seth; Scott Mcdonald, W (2004-03-23). Facial Trauma. ISBN 978-0-8247-5008-4.

- ↑ "Ossification". Medcyclopaedia. GE. Archived from the original on 2011-05-26.

- ↑ "II. Osteology. 6a. 2. The Scapula (Shoulder Blade). Gray, Henry. 1918. Anatomy of the Human Body".

- ↑ Paine, Russ; Voight, Michael L. (2016-11-22). "The role of the scapula". International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 8 (5): 617–629. ISSN 2159-2896. PMC 3811730. PMID 24175141.

- ↑ Saladin, K (2010). Anatomy & Physiology. McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Livingston DH, Hauser CJ (2003). "Trauma to the chest wall and lung". In Moore EE, Feliciano DV, Mattox KL (eds.). Trauma. Fifth Edition. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 516. ISBN 0-07-137069-2.

- ↑ van Noort, A; van Kampen, A (Dec 2005). "Fractures of the scapula surgical neck: outcome after conservative treatment in 13 cases" (PDF). Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 125 (10): 696–700. doi:10.1007/s00402-005-0044-y. PMID 16189689. S2CID 11217081. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-19.

- 1 2 Kibler, BW. (1998). The role of the scapula in athletic shoulder function. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 26(2), 325-337.

- ↑ Cools, A., Dewitte, V., Lanszweert, F., Notebaert, D., Roets, A., et al. (2007). Rehabilitation of scapular muscle balance. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 35(10), 1744.

- 1 2 Anderson, D.M. (2000). Dorland’s illustrated medical dictionary (29th edition). Philadelphia/London/Toronto/Montreal/Sydney/Tokyo: W.B. Saunders Company.

- ↑ Dorland, W.A.N. & Miller, E.C.L. (1948). ‘’The American illustrated medical dictionary.’’ (21st edition). Philadelphia/London: W.B. Saunders Company.

- ↑ Dirckx, J.H. (Ed.) (1997).Stedman’s concise medical dictionary for the health professions. (3rd edition). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

- ↑ Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminology (FCAT) (1998). Terminologia Anatomica. Stuttgart: Thieme

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Hyrtl, J. (1880). Onomatologia Anatomica. Geschichte und Kritik der anatomischen Sprache der Gegenwart. Wien: Wilhelm Braumüller. K.K. Hof- und Universitätsbuchhändler.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Lewis, C.T. & Short, C. (1879). A Latin dictionary founded on Andrews' edition of Freund's Latin dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ↑ Triepel, H. (1910). Die anatomischen Namen. Ihre Ableitung und Aussprache. Mit einem Anhang: Biographische Notizen.(Dritte Auflage). Wiesbaden: Verlag J.F. Bergmann.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- 1 2 3 Kraus, L.A. (1844). Kritisch-etymologisches medicinisches Lexikon (Dritte Auflage). Göttingen: Verlag der Deuerlich- und Dieterichschen Buchhandlung.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Muller, F. (1932). Grieksch woordenboek. (3de druk). Groningen/Den Haag/Batavia: J.B. Wolters’ Uitgevers-Maatschappij N.V.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wageningen, J. van & Muller, F. (1921). Latijnsch woordenboek. (3de druk). Groningen/Den Haag: J.B. Wolters’ Uitgevers-Maatschappij

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Klein, E. (1971). A comprehensive etymological dictionary of the English language. Dealing with the origin of words and their sense development thus illustration the history of civilization and culture. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science B.V.

- ↑ Drosdowski, G. & Grebe (Ed.) (1963). Duden. Etymologie. Herkunfstwörterbuch der deutschen Sprache. Mannheim: Dudenverlag.

- 1 2 3 4 Donald, J. (1880). Chambers's etymological dictionary of the English language.’’ London/Edinburgh: W. & R. Chambers.

- 1 2 Vries, J. de, Tollenaere, F. de & Persijn, A.J. (1993). Etymologisch woordenboek (18de druk). Utrecht: Uitgeverij Het Spectrum B.V.

- 1 2 3 4 Veen, P.A.F. van, Sijs, N. van der (1997). Etymologisch woordenboek. De herkomst van onze woorden.’’ Utrecht/Antwerpen: Van Dale Lexicografie.

- ↑ Martini, M., Graevius, Janszoon van Almeloveen, T. & Clerici, G. (1701). Lexicon philologicum. (Tomus secundus) Amsterdam: Joannes Ludovicus De Lorme.

- 1 2 3 Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 186–187. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- Nickel, Schummer, & Seiferle; Lehrbuch der Anatomie der Haussäugetiere.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scapula. |

- Anatomy photo:10:st-0301 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Joints of the Upper Extremity: Scapula"

- shoulder/bones/bones2 at the Dartmouth Medical School's Department of Anatomy

- shoulder/surface/surface2 at the Dartmouth Medical School's Department of Anatomy

- radiographsul at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (xrayleftshoulder)