Pulp (tooth)

| Pulp | |

|---|---|

Section of a human molar | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | pulpa dentis |

| MeSH | D003782 |

| TA98 | A05.1.03.051 |

| TA2 | 934 |

| FMA | 55631 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

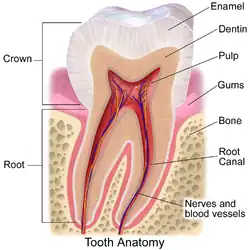

The pulp is the part in the centre of a tooth made up of living connective tissues and odontoblasts. The pulp is a part of the dentin–pulp complex (endodontium).[1] The vitality of the dentin-pulp complex, both during health and after injury, depends on pulp cell activity and the signalling processes that regulate the cell's behaviour.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8]

Anatomy

The pulp is the neurovascular bundle central to each tooth, permanent or primary. It comprises a central pulp chamber, pulp horns, and radicular canals. The large mass of the pulp is contained within the pulp chamber, which is contained in and mimics the overall shape of the crown of the tooth.[2] Because of the continuous deposition of the dentine, the pulp chamber becomes smaller with the age. This is not uniform throughout the coronal pulp but progresses faster on the floor than on the roof or sidewalls.

Radicular pulp canals extend down from the cervical region of the crown to the root apex. They are not always straight but vary in shape, size, and number. They are continuous with the periapical tissues through the apical foramen or foramina.

The total volume of all the permanent teeth organs is 0.38cc and the mean volume of a single adult human pulp is 0.02cc.

Accessory canals are pathways from the radicular pulp. These canals, which extend laterally through the dentin to the periodontal tissue, are seen especially in the apical third of the root. Accessory canals are also called lateral canals because they are usually located on the lateral surface of the roots of the teeth.

Development

The pulp has a background similar to that of dentin because both are derived from the dental papilla of the tooth germ. During odontogenesis, when the dentin forms around the dental papilla, the innermost tissue is considered pulp.[9]

There are 4 main stages of tooth development:

1. Bud stage

2. Cap stage

3. Bell stage

4. Crown stage

The first sign of tooth development is known to be as early as the 6th week of intrauterine life. The oral epithelium begins to multiply and invaginates into ectomesenchyme cells which gives rise to dental lamina. The dental lamina is the origin of the tooth bud. The bud stage progresses to the cap stage when the epithelium forms the enamel organ. The ectomesenchyme cells condense further and become dental papilla. Together the epithelial enamel organ and ectomesenchymal dental papilla and follicle form the tooth germ. The dental papilla is the origin of dental pulp. Cells at the periphery of the dental papilla undergo cell division and differentiation to become odontoblasts. Pulpoblasts form in the middle of the pulp. This completes the formation of the pulp. The dental pulp is essentially a mature dental papilla.[11]

The development of dental pulp can also be split into two stages: coronal pulp development (near the crown of the tooth) and root pulp development (apex of the tooth).

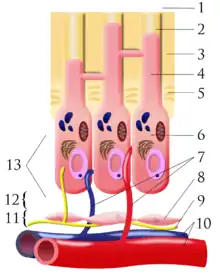

The pulp develops in four regions from the periphery to the central pulp:

- Odontoblast layer

- Cell-free zone – likely to be an artefact

- Cell-rich zone

- Pulp core[12]

Internal structure

The central region of the coronal and radicular pulp contains large nerve trunks and blood vessels.

This area is lined peripherally by a specialized odontogenic area which has four layers (from innermost to outermost):

- Pulpal core, which is in the center of the pulp chamber with many cells and an extensive vascular supply; except for its location, it is very similar to the cell-rich zone.

- Cell-rich zone; which contains fibroblasts and undifferentiated mesenchymal cells.

- Cell-free zone (zone of Weil) which is rich in both capillaries and nerve networks.

- Odontoblastic layer; outermost layer which contains odontoblasts and lies next to the predentin and mature dentin.

Cells found in the dental pulp include fibroblasts (the principal cell), odontoblasts, defence cells like histiocytes, macrophages, granulocytes, mast cells, and plasma cells. The nerve plexus of Raschkow is located central to the cell-rich zone.[9]

The Plexus of Raschkow

The plexus of Raschkow monitors painful sensations. By virtue of their peptide content, they also play important functions in inflammatory events and subsequent tissue repair. There are two types of nerve fiber that mediate the sensation of pain: A-fibers conduct rapid and sharp pain sensations and belong to the myelinated group, whereas C-fibers are involved in dull aching pain and are thinner and unmyelinated. The A-fibers, mainly of the A-delta type, are preferentially located in the periphery of the pulp, where they are in close association with the odontoblasts and extend fibers to many but not all dentinal tubules. The C-fibers typically terminate in the pulp tissue proper, either as free nerve endings or as branches around blood vessels. Sensory nerve fibers that originate from inferior and superior alveolar nerves innervate the odontoblastic layer of the pulp cavity. These nerves enter the tooth through the apical foramen as myelinated nerve bundles. They branch to form the subodontoblastic nerve plexus of Raschkow which is separated from the odontoblasts by a cell-free zone of Weil. Therefore, this plexus lies between the cell-free and cell-rich zones of the pulp.

Pulp Innervation

As the dental pulp is a highly vascularised and innervated region of the tooth, it is the site of origin for most pain-related sensations.[13] The dental pulp nerve is innervated by one of the trigeminal nerves, otherwise known as the fifth cranial nerve. The neurons enter the pulp cavity through the apical foramen and branch off to form the nerve plexus of Raschkow (as mentioned earlier). Nerves from the plexus of Raschkow give branches to form a marginal plexus around the odontoblasts, with some nerves penetrating the dentinal tubules.

The dental pulp is also innervated by the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system.[12] These sympathetic axons project into the radicular pulp, where they form a plexus along the blood vessels. Their function is mainly related to blood vessel constriction within the dental pulp.[12] Hence, it is very possible that a sharp fall in pulpal blood flow may be caused by stimulation of these nerves. There is no evidence for a parasympathetic pulpal innervation.

There are two main types of sensory nerve fibres in the pulp, each densely placed at different locations. Moreover, the differing structural features of the two sensory nerve fibres also result in different types of sensory stimulation.

- Myelinated A-Fibres:

- The A-Fibres present in the pulp can be further classified into 2 different types. A-delta Fibres make up 90% of the A-Fibres, while the rest are A-Beta Fibres.[14]

- A relatively low-threshold sensory apparatus.

- Mainly located at the pulp-dentine border at the top of the pulp, and more specifically concentrated in the pulp horn.[12]

- They have a relatively small diameter, and thus a relatively slow conduction velocity. However, they are is still faster than C-Fibres.[12]

- A-Fibres transmit signals to the brainstem and then to the contralateral thalamus.

- Able to respond to stimuli through a shell of calcified tissue due to the stimulus-induced fluid flow in dentinal tubules.[15] This is known as the hydrodynamic theory. Stimuli that displaces the fluid within the dentinal tubules will trigger the intradental myelinated A-Fibres, leading to a sharp pain sensation,[15] commonly associated with dentine hypersensitivity

- Unmyelinated C-Fibres:

- They are mainly located at the core of the pulp and extend underneath the odontoblastic layer.

- On the contrary, C-Fibres have higher thresholds, responsible for detecting inflammatory threats.[16]

- They are heavily influenced by modulating interneurons before they reach the thalamus. Therefore, C-Fibre stimulation often results in a “slow pain”, normally characterised as a dull and aching pain.[12]

Functions

The primary function of the dental pulp is to form dentin (by the odontoblasts).

Other functions include:

- Nutritive: the pulp keeps the organic components of the surrounding mineralized tissue supplied with moisture and nutrients;

- Protective/Sensory: extremes in temperature, pressure, or trauma to the dentin or pulp are perceived as pain;

- Defensive/reparative: the formation of reparative or tertiary dentin (by the odontoblasts);

- Formative: cells of the pulp produce dentin which surrounds and protects the pulpal tissue.

Pulp Testing

The health of the dental pulp can be established by a variety of diagnostic aids which test either the blood supply to a tooth (Vitality Test) or the sensory response of the nerves within the root canal to specific stimuli (Sensitivity Test). Although less accurate, sensitivity tests, such as Electric Pulp Tests or Thermal Tests, are more routinely used in clinical practice than vitality testing which requires specialised equipment.

A healthy tooth is expected to respond to sensitivity testing with a short, sharp burst of pain which subsides when the stimulus is removed. An exaggerated or prolonged response to sensitivity testing indicates that the tooth has some degree of symptomatic pulpitis. A tooth that does not respond at all to sensitivity testing may have become necrotic.

Pulp Diagnoses

Normal Pulp

In a healthy tooth pulp, enamel and dentin layers protect the pulp from infection.

Reversible Pulpitis

Reversible pulpitis is a mild to moderate inflammation of dental pulp caused by any momentary irritation or stimulant whereby no pain is felt upon removal of stimulants.[17] The pulp swells when the protective layers of enamel and dentine are compromised. Unlike irreversible pulpitis, the pulp still gives a regular response to sensibility tests and inflammation resolves with management of the cause. There are no significant radiographic changes in the periapical region hence further examination is mandatory to ensure that the dental pulp has returned to its normal healthy state.[18]

Common Causes [17]

- Bacterial infection from caries

- Thermal shock

- Trauma

- Excessive dehydration of a cavity during restoration

- Irritation of exposed dentine

- Repetitive trauma caused by bruxism (tooth grinding) or jaw misalignment

- Fractured tooth exposing pulp

Symptoms [17]

- Temporary post-restoration sensitivity

- Pain is non-spontaneous and is milder compared to irreversible pulpitis

- Short sharp pain due to a stimulant

How it is diagnosed[6]

- X-rays to determine extent of tooth decay and inflammation

- Sensitivity tests to see if pain or discomfort is experienced when tooth is in contact with hot, cold or sweet stimuli

- Tooth tap test (lightweight, blunt instrument gently tapped onto affected tooth to determine extent of inflammation)

- Electric pulp test

Treatment [6]

- Treatment aetiology should resolve reversible pulpitis; treating it early may help prevent irreversible pulpitis

- Follow-up after treatment required to determine whether the reversible pulpitis has returned to a normal status

Prevention [17]

- Regular check-ups for carcinogenic or non-carcinogenic caries

- When preparing cavities, dehydrate with adequate amount of alcohol or chloroform and apply enough varnish to protect the pulp

Irreversible Pulpitis

Pulpitis is established when the pulp chamber is compromised by bacterial infection. Irreversible pulpitis is diagnosed when the pulp of the tooth is inflamed and infected beyond the point of no return, healing of the pulp is not possible. Removal of the aetiological agent will not permit healing and often root canal treatment is indicated. Irreversible pulpitis is commonly a sequel to reversible pulpitis when early intervention is not taken.[6][8] It is key to note that in this stage of the disease progression, the pulp is still vital and vascularised; it is not classified as ‘dead pulp’ until necrosis occurs.[3]

Irreversible and reversible pulpitis are differentiated from each other based on the various pain responses that they have to thermal stimulation. If the condition is reversible then the pulp's pain response will last momentarily upon exposure to cold or hot substances; a few seconds. However, if the pain lingers from minutes to hours, then the condition is irreversible. This is a common presenting complaint that facilitates diagnoses before further investigations e.g. sensibility tests and peri-apical radiographs are proceeded.[3][5]

Diagnosis of irreversible pulpitis is branched into two sub-divisions: symptomatic and asymptomatic. Asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis is a transition of symptomatic irreversible pulpitis into an inactive and quiescent state. This is due to the nature of its causation; the inflammatory exudate can be quickly removed e.g. through a large carious cavity or previous trauma that caused painless exposure of pulp. It is the build-up of pressure in a confined pulp space that stimulates nerve fibres and initiates pain reflexes. When this pressure is relieved, pain is not experienced.[4][7]

As the names imply, these diseases are largely characterised by the symptoms they present, duration and location of pain, causing and relieving factors. A clinician's role is to gather all this information systematically. This will be a compilation of clinical tests (cold ethyl chloride, EPT, hot-gutta percha, palpation), radiographic analysis (peri-apical and/or cone-beam computed tomography) and any further tests deemed necessary. Thermal tests are subjective by nature, so performed on not only the compromised tooth but the adjacent and contralateral teeth as well, allowing the patient to compare information and give the clinician more accurate responses. Normal healthy teeth are used as a baseline for diagnoses.[19][8][6]

The following are key characteristics of each pathology:

Symptomatic irreversible pulpitis:

- Very spontaneous and unpredictable pain. Can occur at any time of day and specific causing factors cannot be labelled.

- Patient may complain of sharp lingering pains, that last longer than 30 seconds even after removal of stimulus.

- There may be referred pain

- Pain may be more pronounced after changes of posture e.g. from lying down to standing up

- Analgesics tend to be ineffective

- As the bacteria have not yet progressed to the peri-apical region, there is no pain on percussion.

Asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis

- There are no clinical symptoms

- Pulp will respond to sensibility tests as a healthy pulp would [6][8]

Treatments: Require endodontic (root canal) treatment or tooth extraction. In endodontic therapy, removal of the inflamed pulp relieves the pain. The empty root canal system is then obturated with Gutta-Percha which is a rubber material that acts as a pressure and pain reliever.[20]

Pulp Necrosis

Pulp necrosis describes when the pulp of a tooth has become necrotic. The pulp tissue is either dead or dying, this may be for a number of reasons including untreated caries, trauma or bacterial infection. It is often subsequent to chronic pulpitis. Teeth with pulp necrosis will need to undergo root canal treatment or extraction to prevent further spread of infection which may lead to an abscess.

Symptoms

Pulp necrosis may be symptomatic or asymptomatic for the patient. If the necrosis is symptomatic it could result in lingering pain to hot and cold stimuli, spontaneous pain that may cause a patient to wake up during sleep, difficulty with eating and being tender to percussion.[21][22] If the necrosis is asymptomatic it will be non-responsive to thermal stimuli or electric pulp tests, the patient may even be unaware of the pathology.[22]

Diagnosis

If the pulpal necrosis is asymptomatic it may go unnoticed by the patient and so a diagnosis may be missed without the use of special tests. To determine if pulp necrosis is present a dentist may take radiographic images (X-rays) and sensitivity testing e.g. hot or cold stimuli (using warm gutta-percha or ethyl chloride); or they may use an electric pulp tester. The vitality of a tooth, which refers to the blood supply to a tooth, may be assessed using doppler flowmetry.[23] Sequelae of a necrotic pulp include acute apical periodontitis, dental abscess, or radicular cyst and discolouration of the tooth.[24]

Prognosis & Treatment

If a necrotic pulp is left untreated it may result in further complications such as infection, fever, swelling, abscesses and bone loss.[25] Currently, there are only two treatment options for teeth that have undergone pulpal necrosis.[26][27] Future treatments aim to assess the revascularization of pulp tissue using techniques such as cell homing.[26]

Pulp response to caries

Pulpal response to caries can be divided into two stages – non-infected pulp and infected pulp. In caries-affected human teeth, there are odontoblast-like cells at the dentine-pulp interface and specialized pulp immune cells to combat caries. Once they identify specific bacterial components, these cells activate innate and adaptive aspects of dental pulp immunity.

In a non-infected pulp, leukocytes are present to sample biologically and respond to the surrounding environment, including macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), T cells and B cells.[15] This sampling process is part of the normally protective immune response as it triggers leukocytes from the circulatory system to adhere to endothelial cells lining blood vessels and then migrate to the site of infection for defence potential. Macrophages can phagocytose bacteria and activate T cells triggering an adaptive immune response that occurs in association with DCs.[16] In the pulp, DCs secrete a range of cytokines that influence both innate and adaptive immune responses, and they are considered key regulators of the tissue’s defence against infection.[28] There is also a comparatively small number of B cells present in the healthy pulp tissue, and as there is pulpitis and caries progression, their numbers also increase.[28]

When bacteria get closer to the pulp but are still confined to primary or secondary dentine, acid demineralization of dentine will occur, leading to the production of tertiary dentine to help protect the pulp from further insult.

After a pulp exposure, pulp cells are recruited, then differentiate into odontoblast-like cells, and contribute to the formation of a dentine bridge and thus increasing the residual dentin thickness.[29] The odontoblast-like cell is a mineralized structure formed by a new population of pulp-derived which can be expressed as Toll-like receptors. They are responsible for the upregulation of innate immunity effectors, including antimicrobial agents and chemokines. One important antimicrobial agent produced by odontoblast is beta-defensins (BDs). BDs kill microorganisms by forming micropores that destroy membrane integrity and cause leakage of the cell content.[30] Another one is nitric oxide (NO), a highly diffusible free radical, which stimulates the production of chemokine to attract immune cells into the affected areas and neutralize bacterial by-products in human pulp cells in vitro.[30]

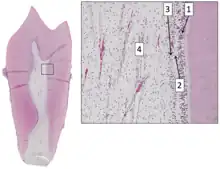

Pulp Stones

Pulp stones are calcified masses that occur in the pulp, either in the apical or coronal portions. They are classified according to their structure or location. According to their location, pulp stones can either be classed as free (completely surrounded by soft pulp tissue), embedded (surrounded by dentine tissue) or adherent (attached to pulp wall and are continuous with dentine but not fully enclosed).[31] Depending on the structure of the pulp stones they are either true (dentine lined by odontoblasts), false (formed from degenerating cells that mineralise) or diffuse (more irregular in shape to false stones).[32] The cause of pulp stones is little understood however it has been recorded that pulpal calcifications can occur due to:

- Pulp degeneration

- Increasing age (especially in the 4th advancing decade)

- Orthodontic treatment

- Trauma - traumatic occlusion

- Dental caries [33]

Histologically, pulp stones usually consist of circular layers of mineralised tissues. These layers are made up of blood clots, dead cells and collagen fibres. Occasionally, pulp stones can be seen to be surrounded by odontoblast like cells that contain tubules. However, this type of pulp stone is rarely seen.[34]

The prevalence of pulp stones can reach as high as 50% in surveyed samples however pulp stones are estimated to range from 8-9%.[31] Pulpal calcifications are more commonly found in females and more frequently found in maxillary teeth compared to mandibular teeth although the reason is unknown. They are also more common in molar teeth especially first molars compared to second molars and premolars.[33] A systematic review suggested that the reason for this was because the first molars are the first teeth to be located in the mandible (lower jaw) and therefore longer exposure to degenerative changes. It also has a larger blood supply.[33]

In general, pulp stones do not require any treatment, however, depending on the size and location of the stones they may interfere with endodontic treatment and therefore be removed.

Complications

Pulp acts as a security and alarm system for a tooth. Slight decay in tooth structure not extending to the dentin may not alarm the pulp but as the dentin gets exposed, either due to dental caries or trauma, sensitivity starts. The dentinal tubules pass the stimulus to odontoblastic layer of the pulp which in turn triggers the response. This mainly responds to cold. At this stage, simple restoration can be performed for treatment. As the decay progresses near the pulp the response also magnifies and sensation to a hot diet as well as cold increases. At this stage, indirect pulp capping might work for treatment but at times it is impossible to clinically diagnose the extent of decay, pulpitis may elicit at this stage. Carious dentin by dental decay progressing to the pulp may get fractured during mastication causing direct trauma to the pulp hence eliciting pulpitis.

The inflammation of the pulp is known as pulpitis. Pulpitis can be extremely painful and in serious cases calls for root canal therapy or endodontic therapy.[35] Traumatized pulp starts an inflammatory response but due to the hard and closed surroundings of the pulp pressure builds inside the pulp chamber compressing the nerve fibres and eliciting extreme pain (acute pulpitis). At this stage, the death of the pulp starts which eventually progresses to periapical abscess formation (chronic pulpitis).

The pulp horns recede with age. Also with increased age, the pulp undergoes a decrease in intercellular substance, water, and cells as it fills with an increased amount of collagen fibers. This decrease in cells is especially evident in the reduced number of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells. Thus, the pulp becomes more fibrotic with increased age, leading to a reduction in the regenerative capacity of the pulp due to its loss of these cells. Also, the overall pulp cavity may be smaller by the addition of secondary or tertiary dentin, thus causing pulp recession. The lack of sensitivity associated with older teeth is due to receded pulp horns, pulp fibrosis, the addition of dentin, or possibly all these age-related changes; many times restorative treatment can be performed without local anaesthesia on older dentitions.[2]

See also

References

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-02-20. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 1 2 3 Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, Bath-Balogh and Fehrenbach, Elsevier, 2011, page 164.

- 1 2 3 Gutmann JL, Lovdahl PE (2011). Problem Solving in the Diagnosis of Odontogenic Pain in problem solving in endodontics (Fifth ed.).

- 1 2 Michaelson PL, Holland GR (October 2002). "Is pulpitis painful?". International Endodontic Journal. 35 (10): 829–32. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2591.2002.00579.x. PMID 12406376.

- 1 2 Iqbal M, Kim S, Yoon F (May 2007). "An investigation into differential diagnosis of pulp and periapical pain: a PennEndo database study". Journal of Endodontics. 33 (5): 548–51. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2007.01.006. PMID 17437869.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Endodontic diagnosis" (PDF). American Association of Endodontics. 2013.

- 1 2 Rôças IN, Lima KC, Assunção IV, Gomes PN, Bracks IV, Siqueira JF (September 2015). "Advanced Caries Microbiota in Teeth with Irreversible Pulpitis". Journal of Endodontics. 41 (9): 1450–5. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2015.05.013. PMID 26187422.

- 1 2 3 4 Glickman G, Schweitzer J (2016). "universal classification in endodontic diagnosis". Journal of Multidisciplinary Care.

- 1 2 Antonio Nanci, Ten Cate's Oral Histology, Elsevier, 2007, page 91

- ↑ "SDEO". www.sdeo.ac.uk. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ↑ Hand AR (2014-11-21). Fundamentals of oral histology and physiology. Frank, Marion E. (Marion Elizabeth), 1940-. Ames, Iowa. ISBN 978-1-118-93831-7. OCLC 891186059.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Goldberg M (2014-07-30). The dental pulp : biology, pathology, and regenerative therapies. Heidelberg. ISBN 978-3-642-55160-4. OCLC 885561103.

- ↑ Schuh CM, Benso B, Aguayo S (2019-09-18). "Potential Novel Strategies for the Treatment of Dental Pulp-Derived Pain: Pharmacological Approaches and Beyond". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 10: 1068. doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.01068. PMC 6759635. PMID 31620000.

- ↑ "Dental Pulp Neurophysiology: Part 1. Clinical and Diagnostic Implications". www.cda-adc.ca. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- 1 2 3 Langenbach F, Naujoks C, Smeets R, Berr K, Depprich R, Kübler N, Handschel J (January 2013). "Scaffold-free microtissues: differences from monolayer cultures and their potential in bone tissue engineering". Clinical Oral Investigations. 17 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1007/s00784-012-0887-x. PMC 3585766. PMID 22695872.

- 1 2 Fried K, Gibbs JL (2014), Goldberg M (ed.), "Dental Pulp Innervation", The Dental Pulp, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 75–95, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-55160-4_6, ISBN 978-3-642-55159-8

- 1 2 3 4 Hedge J (2008). Prep Manual for Undergraduates: Endodontics. India: Reed Elsevier India Private Limited. p. 29. ISBN 978-81-312-1056-7.

- ↑ "Endodontic Diagnosis" (PDF). American Association of Endodontics. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ↑ Chen E, Abbott PV (2009). "Dental pulp testing: a review". International Journal of Dentistry. 2009: 365785. doi:10.1155/2009/365785. PMC 2837315. PMID 20339575.

- ↑ Yoo, Hugo Hb; Nunes-Nogueira, Vania Santos; Fortes Villas Boas, Paulo J. (7 February 2020). "Anticoagulant treatment for subsegmental pulmonary embolism". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD010222. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010222.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7004894. PMID 32030721.

- ↑ "Differential Diagnosis of Toothache Pain: Part 1, Odontogenic Etiologies | Dentistry Today". www.dentistrytoday.com.

- 1 2 "Endodontic diagnosis: If it looks like a horse". www.dentaleconomics.com. December 2007.

- ↑ Jafarzadeh H (June 2009). "Laser Doppler flowmetry in endodontics: a review". International Endodontic Journal. 42 (6): 476–90. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2591.2009.01548.x. PMID 19459999.

- ↑ Nusstein JM, Reader A, Drum M (April 2010). "Local anesthesia strategies for the patient with a "hot" tooth". Dental Clinics of North America. 54 (2): 237–47. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2009.12.003. PMID 20433976.

- ↑ "Pulp Necrosis: Symptoms, Tests, Causes, Risks, and Treatments". Healthline. February 2018.

- 1 2 Eramo S, Natali A, Pinna R, Milia E (April 2018). "Dental pulp regeneration via cell homing". International Endodontic Journal. 51 (4): 405–419. doi:10.1111/iej.12868. PMID 29047120.

- ↑ Oxford M (1 January 2014). "Tooth trauma: pathology and the treatment options". In Practice. 36 (1): 2–14. doi:10.1136/inp.f7208. ISSN 0263-841X. S2CID 76350641.

- 1 2 Farges JC, Alliot-Licht B, Renard E, Ducret M, Gaudin A, Smith AJ, Cooper PR (2015). "Dental Pulp Defence and Repair Mechanisms in Dental Caries". Mediators of Inflammation. 2015: 230251. doi:10.1155/2015/230251. PMC 4619960. PMID 26538821.

- ↑ Charles A Janeway J, Travers P, Walport M, Shlomchik MJ (2001). "Principles of innate and adaptive immunity". Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. 5th Edition.

- 1 2 Goldberg M, ed. (2014). The Dental Pulp. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-55160-4. ISBN 978-3-642-55159-8.

- 1 2 Gabardo MC, Wambier LM, Rocha JS, Küchler EC, de Lara RM, Leonardi DP, et al. (September 2019). "Association between Pulp Stones and Kidney Stones: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Journal of Endodontics. 45 (9): 1099–1105.e2. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2019.06.006. PMID 31351581. S2CID 198966934.

- ↑ Goga R, Chandler NP, Oginni AO (June 2008). "Pulp stones: a review". International Endodontic Journal. 41 (6): 457–68. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01374.x. PMID 18422587.

- 1 2 3 Jannati R, Afshari M, Moosazadeh M, Allahgholipour SZ, Eidy M, Hajihoseini M (May 2019). "Prevalence of pulp stones: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine. 12 (2): 133–139. doi:10.1111/jebm.12331. PMID 30461204. S2CID 53945208.

- ↑ Nanci A (2017-10-13). Ten Cate's oral histology : development, structure, and function. ISBN 978-0-323-48524-1. OCLC 990257609.

- ↑ "Root canal treatment (endodontic therapy) explained: What is it? Why is it needed? What does it do?".

Further reading

- Yu C, Abbott PV (March 2007). "An overview of the dental pulp: its functions and responses to injury". Australian Dental Journal. 52 (1 Suppl): S4–16. doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.2007.tb00525.x. PMID 17546858.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. (2009). "Guideline on pulp therapy for primary and immature permanent teeth" (PDF). Pediatr Dent. 31 (6): 179–86.