Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation

Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UVGI) is a disinfection method that uses short-wavelength ultraviolet (ultraviolet C or UV-C) light to kill or inactivate microorganisms by destroying nucleic acids and disrupting their DNA, leaving them unable to perform vital cellular functions.[1] UVGI is used in a variety of applications, such as food, air, and water purification.

UV-C light is weak at the Earth's surface since the ozone layer of the atmosphere blocks it.[2] UVGI devices can produce strong enough UV-C light in circulating air or water systems to make them inhospitable environments to microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, molds, and other pathogens. UVGI can be coupled with a filtration system to sanitize air and water.

The application of UVGI to disinfection has been an accepted practice since the mid-20th century. It has been used primarily in medical sanitation and sterile work facilities. Increasingly, it has been employed to sterilize drinking and wastewater since the holding facilities are enclosed and can be circulated to ensure a higher exposure to the UV. UVGI has found renewed application in air purifiers.

History

In 1878, Arthur Downes and Thomas P. Blunt published a paper describing the sterilization of bacteria exposed to short-wavelength light.[3] UV has been a known mutagen at the cellular level for over 100 years. The 1903 Nobel Prize for Medicine was awarded to Niels Finsen for his use of UV against lupus vulgaris, tuberculosis of the skin.[4]

Using UV light for disinfection of drinking water dates back to 1910 in Marseille, France.[5] The prototype plant was shut down after a short time due to poor reliability. In 1955, UV water treatment systems were applied in Austria and Switzerland; by 1985 about 1,500 plants were employed in Europe. In 1998 it was discovered that protozoa such as cryptosporidium and giardia were more vulnerable to UV light than previously thought; this opened the way to wide-scale use of UV water treatment in North America. By 2001, over 6,000 UV water treatment plants were operating in Europe.[6]

Over time, UV costs have declined as researchers develop and use new UV methods to disinfect water and wastewater. Several countries, including the United States, have developed regulations that allow systems to disinfect their drinking water supplies with UV light.[7][8] In 2006, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) published a guidance manual for implementation of ultraviolet disinfection of drinking water.[9]

Method of operation

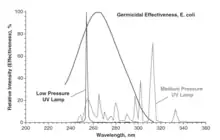

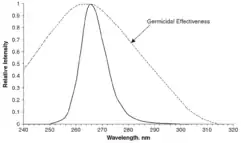

UV light is electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths shorter than visible light but longer than X-rays. UV is categorised into several wavelength ranges, with short-wavelength UV (UV-C) considered "germicidal UV". Wavelengths between about 200 nm and 300 nm are strongly absorbed by nucleic acids. The absorbed energy can result in defects including pyrimidine dimers. These dimers can prevent replication or can prevent the expression of necessary proteins, resulting in the death or inactivation of the organism.

- Mercury-based lamps operating at low vapor pressure emit UV light at the 253.7 nm line.[11]

- Ultraviolet light-emitting diode (UV-C LED) lamps emit UV light at selectable wavelengths between 255 and 280 nm.[12]

- Pulsed-xenon lamps emit UV light across the entire UV spectrum with a peak emission near 230 nm.[10]

This process is similar to, but stronger than, the effect of longer wavelengths (UV-B) producing sunburn in humans. Microorganisms have less protection against UV and cannot survive prolonged exposure to it.

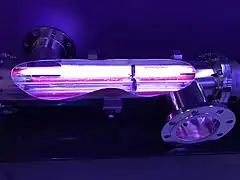

A UVGI system is designed to expose environments such as water tanks, sealed rooms and forced air systems to germicidal UV. Exposure comes from germicidal lamps that emit germicidal UV at the correct wavelength, thus irradiating the environment. The forced flow of air or water through this environment ensures exposure.

Effectiveness

The effectiveness of germicidal UV depends on the duration a microorganism is exposed to UV, the intensity and wavelength of the UV radiation, the presence of particles that can protect the microorganisms from UV, and a microorganism's ability to withstand UV during its exposure.

In many systems, redundancy in exposing microorganisms to UV is achieved by circulating the air or water repeatedly. This ensures multiple passes so that the UV is effective against the highest number of microorganisms and will irradiate resistant microorganisms more than once to break them down.

"Sterilization" is often misquoted as being achievable. While it is theoretically possible in a controlled environment, it is very difficult to prove and the term "disinfection" is generally used by companies offering this service as to avoid legal reprimand. Specialist companies will often advertise a certain log reduction, e.g., 6-log reduction or 99.9999% effective, instead of sterilization. This takes into consideration a phenomenon known as light and dark repair (photoreactivation and base excision repair, respectively), in which a cell can repair DNA that has been damaged by UV light.

The effectiveness of this form of disinfection depends on line-of-sight exposure of the microorganisms to the UV light. Environments where design creates obstacles that block the UV light are not as effective. In such an environment, the effectiveness is then reliant on the placement of the UVGI system so that line of sight is optimum for disinfection.

Dust and films coating the bulb lower UV output. Therefore, bulbs require periodic cleaning and replacement to ensure effectiveness. The lifetime of germicidal UV bulbs varies depending on design. Also, the material that the bulb is made of can absorb some of the germicidal rays.

Lamp cooling under airflow can also lower UV output. Increases in effectiveness and UV intensity can be achieved by using reflection. Aluminum has the highest reflectivity rate versus other metals and is recommended when using UV.[13]

One method for gauging UV effectiveness in water disinfection applications is to compute UV dose. EPA published UV dosage guidelines for water treatment applications in 1986.[14] UV dose cannot be measured directly but can be inferred based on the known or estimated inputs to the process:

- Flow rate (contact time)

- Transmittance (light reaching the target)

- Turbidity (cloudiness)

- Lamp age or fouling or outages (reduction in UV intensity)

In air and surface disinfection applications the UV effectiveness is estimated by calculating the UV dose which will be delivered to the microbial population. The UV dose is calculated as follows:

- UV dose (μW·s/cm2) = UV intensity (μW/cm2) × exposure time (seconds)[15]

The UV intensity is specified for each lamp at a distance of 1 meter. UV intensity is inversely proportional to the square of the distance so it decreases at longer distances. Alternatively, it rapidly increases at distances shorter than 1 m. In the above formula, the UV intensity must always be adjusted for distance unless the UV dose is calculated at exactly 1 m (3.3 ft) from the lamp. Also, to ensure effectiveness, the UV dose must be calculated at the end of lamp life (EOL is specified in number of hours when the lamp is expected to reach 80% of its initial UV output) and at the furthest distance from the lamp on the periphery of the target area. Some shatter-proof lamps are coated with a fluorated ethylene polymer to contain glass shards and mercury in case of breakage; this coating reduces UV output by as much as 20%.

To accurately predict what UV dose will be delivered to the target, the UV intensity, adjusted for distance, coating, and end of lamp life, will be multiplied by the exposure time. In static applications the exposure time can be as long as needed for an effective UV dose to be reached. In case of rapidly moving air, in AC air ducts, for example, the exposure time is short, so the UV intensity must be increased by introducing multiple UV lamps or even banks of lamps. Also, the UV installation must be located in a long straight duct section with the lamps perpendicular to the airflow to maximize the exposure time.

These calculations actually predict the UV fluence and it is assumed that the UV fluence will be equal to the UV dose. The UV dose is the amount of germicidal UV energy absorbed by a microbial population over a period of time. If the microorganisms are planktonic (free floating) the UV fluence will be equal the UV dose. However, if the microorganisms are protected by mechanical particles, such as dust and dirt, or have formed biofilm a much higher UV fluence will be needed for an effective UV dose to be introduced to the microbial population.

Inactivation of microorganisms

The degree of inactivation by ultraviolet radiation is directly related to the UV dose applied to the water. The dosage, a product of UV light intensity and exposure time, is usually measured in microjoules per square centimeter, or equivalently as microwatt seconds per square centimeter (μW·s/cm2). Dosages for a 90% kill of most bacteria and viruses range between 2,000 and 8,000 μW·s/cm2. Larger parasites such as cryptosporidium require a lower dose for inactivation. As a result, US EPA has accepted UV disinfection as a method for drinking water plants to obtain cryptosporidium, giardia or virus inactivation credits. For example, for a 90% reduction of cryptosporidium, a minimum dose of 2,500 μW·s/cm2 is required based on EPA's 2006 guidance manual.[9]: 1–7

Strengths and weaknesses

Advantages

UV water treatment devices can be used for well water and surface water disinfection. UV treatment compares favourably with other water disinfection systems in terms of cost, labour and the need for technically trained personnel for operation. Water chlorination treats larger organisms and offers residual disinfection, but these systems are expensive because they need special operator training and a steady supply of a potentially hazardous material. Finally, boiling of water is the most reliable treatment method but it demands labour and imposes a high economic cost. UV treatment is rapid and, in terms of primary energy use, approximately 20,000 times more efficient than boiling.

Disadvantages

UV disinfection is most effective for treating high-clarity, purified reverse osmosis distilled water. Suspended particles are a problem because microorganisms buried within particles are shielded from the UV light and pass through the unit unaffected. However, UV systems can be coupled with a pre-filter to remove those larger organisms that would otherwise pass through the UV system unaffected. The pre-filter also clarifies the water to improve light transmittance and therefore UV dose throughout the entire water column. Another key factor of UV water treatment is the flow rate—if the flow is too high, water will pass through without sufficient UV exposure. If the flow is too low, heat may build up and damage the UV lamp.[16]

A disadvantage of UVGI is that while water treated by chlorination is resistant to reinfection (until the chlorine off-gasses), UVGI water is not resistant to reinfection. UVGI water must be transported or delivered in such a way as to avoid reinfection.

Safety

To humans

UV light is hazardous to most living things. Skin exposure to germicidal wavelengths of UV light can produce rapid sunburn and skin cancer. Exposure of the eyes to this UV radiation can produce extremely painful inflammation of the cornea and temporary or permanent vision impairment, up to and including blindness in some cases.[17] Common precautions are:[18]

- Warning labels warn humans about dangers of UV light. In home settings with children and pets, doors are additionally necessary.

- Interlock systems. Shielded systems where the light is blocked inside, such as a closed water tank or closed air circulation system, often has interlocks that automatically shut off the UV lamps if the system is opened for access by humans. Clear viewports that block UVC are available.

- Protective gear. Most protective eyewear (in particular, all ANSI Z87.1-compliant eyewear) block UVC. Clothing, plastics, and most types of glass (but not fused silica) are effective in blocking UVC.[19]

Another potential danger is the UV production of ozone, which can be harmful when inhaled. US EPA designated 0.05 parts per million (ppm) of ozone to be a safe level. Lamps designed to release UV and higher frequencies are doped so that any UV light below 254 nm wavelengths will not be released, to minimize ozone production. A full-spectrum lamp will release all UV wavelengths and produce ozone when UV-C hits oxygen (O2) molecules.

The American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) Committee on Physical Agents has established a threshold limit value (TLV) for UV exposure to avoid such skin and eye injuries among those most susceptible. For 254 nm UV, this TLV is 6 mJ/cm2 over an eight-hour period. The TLV function differs by wavelengths because of variable energy and potential for cell damage. This TLV is supported by the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection and is used in setting lamp safety standards by the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America. When the Tuberculosis Ultraviolet Shelter Study was planned, this TLV was interpreted as if eye exposure in rooms was continuous over eight hours and at the highest eye-level irradiance found in the room. In those highly unlikely conditions, a 6.0 mJ/cm2 dose is reached under the ACGIH TLV after just eight hours of continuous exposure to an irradiance of 0.2 μW/cm2. Thus, 0.2 μW/cm2 was widely interpreted as the upper permissible limit of irradiance at eye height.[20]

According to the FDA, a germicidal excimer lamp that emits 222 nm light instead of the common 254 nm light is safer to mamallian skin.[21]

To items

UVC radiation is able to break down chemical bonds. This leads to rapid aging of plastics, insulation, gaskets, and other materials. Note that plastics sold to be "UV-resistant" are tested only for the lower-energy UVB since UVC does not normally reach the surface of the Earth.[22] When UV is used near plastic, rubber, or insulation, these materials may be protected by metal tape or aluminum foil.

Uses

Air disinfection

UVGI can be used to disinfect air with prolonged exposure. In the 1930s and 40s, an experiment in public schools in Philadelphia showed that upper-room ultraviolet fixtures could significantly reduce the transmission of measles among students.[23] In 2020, UVGI is again being researched as a possible countermeasure against the COVID-19 pandemic.[24][25]

UV and violet light are able to neutralize the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2.[26] Viral titers usually found in the sputum of COVID-19 patients are completely inactivated by levels of UV-A and UV-B irradiation that are similar to those levels experienced from natural sun exposure. This finding suggests that the reduced incidence of SARS-COV-2 in the summer may be, in part, due to the neutralizing activity of solar UV irradiation.[26]

Various UV-emitting devices can be used for SARS-CoV-2 disinfection, and these devices may help in reducing the spread of infection.[27] SARS-CoV-2 can be inactivated by a wide range of UVC wavelengths, and the wavelength of 222nm provides the most effective disinfection performance.[27]

Disinfection is a function of UV intensity and time. For this reason, it is in theory not as effective on moving air, or when the lamp is perpendicular to the flow, as exposure times are dramatically reduced. However, numerous professional and scientific publications have indicated that the overall effectiveness of UVGI actually increases when used in conjunction with fans and HVAC ventilation, which facilitate whole-room circulation that exposes more air to the UV source.[28][29] Air purification UVGI systems can be free-standing units with shielded UV lamps that use a fan to force air past the UV light. Other systems are installed in forced air systems so that the circulation for the premises moves microorganisms past the lamps. Key to this form of sterilization is placement of the UV lamps and a good filtration system to remove the dead microorganisms.[30] For example, forced air systems by design impede line-of-sight, thus creating areas of the environment that will be shaded from the UV light. However, a UV lamp placed at the coils and drain pans of cooling systems will keep microorganisms from forming in these naturally damp places.

Water disinfection

Ultraviolet disinfection of water is a purely physical, chemical-free process. Even parasites such as Cryptosporidium or Giardia, which are extremely resistant to chemical disinfectants, are efficiently reduced. UV can also be used to remove chlorine and chloramine species from water; this process is called photolysis, and requires a higher dose than normal disinfection. The dead microorganisms are not removed from the water. UV disinfection does not remove dissolved organics, inorganic compounds or particles in the water.[31] The world's largest water disinfection plant treats drinking water for New York City. The Catskill-Delaware Water Ultraviolet Disinfection Facility, commissioned on 8 October 2013, incorporates a total of 56 energy-efficient UV reactors treating up to 2.2 billion U.S. gallons (8.3 billion liters) a day.[32][33]

Ultraviolet can also be combined with ozone or hydrogen peroxide to produce hydroxyl radicals to break down trace contaminants through an advanced oxidation process.

It used to be thought that UV disinfection was more effective for bacteria and viruses, which have more-exposed genetic material, than for larger pathogens that have outer coatings or that form cyst states (e.g., Giardia) that shield their DNA from UV light. However, it was recently discovered that ultraviolet radiation can be somewhat effective for treating the microorganism Cryptosporidium. The findings resulted in the use of UV radiation as a viable method to treat drinking water. Giardia in turn has been shown to be very susceptible to UV-C when the tests were based on infectivity rather than excystation.[34] It has been found that protists are able to survive high UV-C doses but are sterilized at low doses.

Developing countries

A 2006 project at University of California, Berkeley produced a design for inexpensive water disinfection in resource deprived settings.[35] The project was designed to produce an open source design that could be adapted to meet local conditions. In a somewhat similar proposal in 2014, Australian students designed a system using potato chip (crisp) packet foil to reflect solar UV radiation into a glass tube that disinfects water without power.[36]

Wastewater treatment

Ultraviolet in sewage treatment is commonly replacing chlorination. This is in large part because of concerns that reaction of the chlorine with organic compounds in the waste water stream could synthesize potentially toxic and long lasting chlorinated organics and also because of the environmental risks of storing chlorine gas or chlorine containing chemicals. Individual wastestreams to be treated by UVGI must be tested to ensure that the method will be effective due to potential interferences such as suspended solids, dyes, or other substances that may block or absorb the UV radiation. According to the World Health Organization, "UV units to treat small batches (1 to several liters) or low flows (1 to several liters per minute) of water at the community level are estimated to have costs of US$20 per megaliter, including the cost of electricity and consumables and the annualized capital cost of the unit."[37]

Large-scale urban UV wastewater treatment is performed in cities such as Edmonton, Alberta. The use of ultraviolet light has now become standard practice in most municipal wastewater treatment processes. Effluent is now starting to be recognized as a valuable resource, not a problem that needs to be dumped. Many wastewater facilities are being renamed as water reclamation facilities, whether the wastewater is discharged into a river, used to irrigate crops, or injected into an aquifer for later recovery. Ultraviolet light is now being used to ensure water is free from harmful organisms.

Aquarium and pond

Ultraviolet sterilizers are often used to help control unwanted microorganisms in aquaria and ponds. UV irradiation ensures that pathogens cannot reproduce, thus decreasing the likelihood of a disease outbreak in an aquarium.

Aquarium and pond sterilizers are typically small, with fittings for tubing that allows the water to flow through the sterilizer on its way from a separate external filter or water pump. Within the sterilizer, water flows as close as possible to the ultraviolet light source. Water pre-filtration is critical as water turbidity lowers UV-C penetration. Many of the better UV sterilizers have long dwell times and limit the space between the UV-C source and the inside wall of the UV sterilizer device.[38]

Laboratory hygiene

UVGI is often used to disinfect equipment such as safety goggles, instruments, pipettors, and other devices. Lab personnel also disinfect glassware and plasticware this way. Microbiology laboratories use UVGI to disinfect surfaces inside biological safety cabinets ("hoods") between uses.

Food and beverage protection

Since the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a rule in 2001 requiring that virtually all fruit and vegetable juice producers follow HACCP controls, and mandating a 5-log reduction in pathogens, UVGI has seen some use in sterilization of juices such as fresh-pressed.

Technology

Lamps

Germicidal UV for disinfection is most typically generated by a mercury-vapor lamp. Low-pressure mercury vapor has a strong emission line at 254 nm, which is within the range of wavelengths that demonstrate strong disinfection effect. The optimal wavelengths for disinfection are close to 260 nm.[9]: 2–6, 2–14

Mercury vapor lamps may be categorized as either low-pressure (including amalgam) or medium-pressure lamps. Low-pressure UV lamps offer high efficiencies (approx. 35% UV-C) but lower power, typically 1 W/cm power density (power per unit of arc length). Amalgam UV lamps utilize an amalgam to control mercury pressure to allow operation at a somewhat higher temperature and power density. They operate at higher temperatures and have a lifetime of up to 16,000 hours. Their efficiency is slightly lower than that of traditional low-pressure lamps (approx. 33% UV-C output), and power density is approximately 2–3 W/cm3. Medium-pressure UV lamps operate at much higher temperatures, up to about 800 degrees Celsius, and have a polychromatic output spectrum and a high radiation output but lower UV-C efficiency of 10% or less. Typical power density is 30 W/cm3 or greater.

Depending on the quartz glass used for the lamp body, low-pressure and amalgam UV emit radiation at 254 nm and also at 185 nm, which has chemical effects. UV radiation at 185 nm is used to generate ozone.

The UV lamps for water treatment consist of specialized low-pressure mercury-vapor lamps that produce ultraviolet radiation at 254 nm, or medium-pressure UV lamps that produce a polychromatic output from 200 nm to visible and infrared energy. The UV lamp never contacts the water; it is either housed in a quartz glass sleeve inside the water chamber or mounted externally to the water, which flows through the transparent UV tube. Water passing through the flow chamber is exposed to UV rays, which are absorbed by suspended solids, such as microorganisms and dirt, in the stream.[39]

Light emitting diodes (LEDs)

Recent developments in LED technology have led to commercially available UV-C LEDs. UV-C LEDs use semiconductors to emit light between 255 nm and 280 nm.[12] The wavelength emission is tuneable by adjusting the material of the semiconductor. As of 2019, the electrical-to-UV-C conversion efficiency of LEDs was lower than that of mercury lamps. The reduced size of LEDs opens up options for small reactor systems allowing for point-of-use applications and integration into medical devices.[40] Low power consumption of semiconductors introduce UV disinfection systems that utilized small solar cells in remote or Third World applications.[40]

UV-C LEDs don't necessarily last longer than traditional germicidal lamps in terms of hours used, instead having more-variable engineering characteristics and better tolerance for short-term operation. A UV-C LED can achieve a longer installed time than a traditional germicidal lamp in intermittent use. Likewise, LED degradation increases with heat, while filament and HID lamp output wavelength is dependent on temperature, so engineers can design LEDs of a particular size and cost to have a higher output and faster degradation or a lower output and slower decline over time.

Water treatment systems

Sizing of a UV system is affected by three variables: flow rate, lamp power, and UV transmittance in the water. Manufacturers typically developed sophisticated computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models validated with bioassay testing. This involves testing the UV reactor's disinfection performance with either MS2 or T1 bacteriophages at various flow rates, UV transmittance, and power levels in order to develop a regression model for system sizing. For example, this is a requirement for all public water systems in the United States per the EPA UV manual.[9]: 5–2

The flow profile is produced from the chamber geometry, flow rate, and particular turbulence model selected. The radiation profile is developed from inputs such as water quality, lamp type (power, germicidal efficiency, spectral output, arc length), and the transmittance and dimension of the quartz sleeve. Proprietary CFD software simulates both the flow and radiation profiles. Once the 3D model of the chamber is built, it is populated with a grid or mesh that comprises thousands of small cubes.

Points of interest—such as at a bend, on the quartz sleeve surface, or around the wiper mechanism—use a higher resolution mesh, whilst other areas within the reactor use a coarse mesh. Once the mesh is produced, hundreds of thousands of virtual particles are "fired" through the chamber. Each particle has several variables of interest associated with it, and the particles are "harvested" after the reactor. Discrete phase modeling produces delivered dose, head loss, and other chamber-specific parameters.

When the modeling phase is complete, selected systems are validated using a professional third party to provide oversight and to determine how closely the model is able to predict the reality of system performance. System validation uses non-pathogenic surrogates such as MS 2 phage or Bacillus subtilis to determine the Reduction Equivalent Dose (RED) ability of the reactors. Most systems are validated to deliver 40 mJ/cm2 within an envelope of flow and transmittance.

To validate effectiveness in drinking water systems, the method described in the EPA UV guidance manual is typically used by US water utilities, whilst Europe has adopted Germany's DVGW 294 standard. For wastewater systems, the NWRI/AwwaRF Ultraviolet Disinfection Guidelines for Drinking Water and Water Reuse protocols are typically used, especially in wastewater reuse applications.[41]

See also

- HEPA filter

- Portable water purification

- Sanitation

- Sanitation Standard Operating Procedures

- Solar water disinfection

References

- ↑ "Word of the Month: Ultraviolet Germicidal Irradiation (UVGI)" (PDF). NIOSH eNews. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. April 2008. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ↑ "SOLVE II Science Implementation". NASA. 2003. Archived from the original on February 16, 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ↑ Downes, Arthur; Blunt, Thomas P. (19 December 1878). "On the Influence of Light upon Protoplasm". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 28 (190–195): 199–212. Bibcode:1878RSPS...28..199D. doi:10.1098/rspl.1878.0109.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1903". Nobelprize.org. The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ↑ "Ultraviolet light disinfection in the use of individual water purification devices" (PDF). U.S. Army Public Health Command. Retrieved 2014-01-08.

- ↑ Bolton, James; Colton, Christine (2008). The Ultraviolet Disinfection Handbook. American Water Works Association. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-1-58321-584-5.

- ↑ United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (2006-01-05). "National Primary Drinking Water Regulations: Long Term 2 Enhanced Surface Water Treatment Rule." Federal Register, 71 FR 653

- ↑ "Long Term 2 Enhanced Surface Water Treatment Rule Documents". Washington, DC: EPA. 2021-12-01.

- 1 2 3 4 Ultraviolet Disinfection Guidance Manual for the Final Long Term 2 Enhanced Surface Water Treatment Rule (Report). EPA. November 2006. EPA 815-R-06-007.

- 1 2 3 Kowalski, Wladyslaw (2009). Ultraviolet Germicidal Irradiation Handbook: UVGI for Air and Surface Disinfection. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-01999-9. ISBN 978-3-642-01998-2.

- ↑ Meulemans, C. C. E. (1987-09-01). "The Basic Principles of UV–Disinfection of Water". Ozone: Science & Engineering. 9 (4): 299–313. doi:10.1080/01919518708552146. ISSN 0191-9512.

- 1 2 Messina, Gabriele (October 2015). "A new UV-LED device for automatic disinfection of stethoscope membranes". American Journal of Infection Control. Elsevier. 43 (10): e61-6. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2015.06.019. PMID 26254501. Retrieved 2016-08-15.

- ↑ "Ultra-Violet reflecting power of aluminum and several other metals; W. W. Coblentz and R. Stair".

- ↑ Design Manual: Municipal Wastewater Disinfection (Report). Cincinnati, OH: EPA. October 1986. EPA 625/1-86/021.

- ↑ UV dose

- ↑ Gadgil, A., 1997, Field-testing UV Disinfection of Drinking Water, Water Engineering Development Center, University of Loughborough, UK: LBNL 40360.

- ↑ "Final Opinion". 2016-11-25.

- ↑ "UV-C Lamps: Staying Safe". www.uvresources.com.

- ↑ "Is UVC Safe?". Klaran.

- ↑ Nardell, Edward (January–February 2008). "Safety of Upper-Room Ultraviolet Germicidal Air Disinfection for Room Occupants: Results from the Tuberculosis Ultraviolet Shelter Study" (PDF). UV And People's Health.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Health, Center for Devices and Radiological (19 August 2020). "UV Lights and Lamps: Ultraviolet-C Radiation, Disinfection, and Coronavirus". FDA.

- ↑ Irving, Daniel; Lamprou, Dimitrios A.; Maclean, Michelle; MacGregor, Scott J.; Anderson, John G.; Grant, M. Helen (November 2016). "A comparison study of the degradative effects and safety implications of UVC and 405 nm germicidal light sources for endoscope storage". Polymer Degradation and Stability. 133: 249–254. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2016.09.006.

- ↑ Wells, W.F.; Wells, M.W.; Wilder, T.S. (January 1942). "The environmental control of epidemic contagion. I. An epidemiologic study of radiant disinfection of air in day schools" (PDF). American Journal of Epidemiology. 35 (1): 97–121. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a118789. Retrieved 2020-11-25.

- ↑ Chang, Kenneth (2020-05-07). "Scientists Consider Indoor Ultraviolet Light to Zap Coronavirus in the Air". The New York Times.

- ↑ Beggs CB, Avital EJ (2020). "Upper-room ultraviolet air disinfection might help to reduce COVID-19 transmission in buildings: a feasibility study". PeerJ. 8:e10196: e10196. doi:10.7717/peerj.10196. PMC 7566754. PMID 33083158.

- 1 2 Biasin, Mara; Strizzi, Sergio; Bianco, Andrea; Macchi, Alberto; Utyro, Olga; Pareschi, Giovanni; Loffreda, Alessia; Cavalleri, Adalberto; Lualdi, Manuela; Trabattoni, Daria; Tacchetti, Carlo (2022). "UV and violet light can Neutralize SARS-CoV-2 Infectivity". Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology. 10: 100107. doi:10.1016/j.jpap.2021.100107. PMC 8741330. PMID 35036965.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - 1 2 Ma, Ben; Gundy, Patricia M.; Gerba, Charles P.; Sobsey, Mark D.; Linden, Karl G. (2021-10-28). Dudley, Edward G. (ed.). "UV Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 across the UVC Spectrum: KrCl* Excimer, Mercury-Vapor, and Light-Emitting-Diode (LED) Sources". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 87 (22): e01532–21. doi:10.1128/AEM.01532-21. ISSN 0099-2240. PMC 8552892. PMID 34495736.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions" (PDF). IES Committee Reports. Illuminating Engineering Society. 5 May 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ↑ Ko, Gwangpyo; First, Melvin; Burge, Harriet (Jan 2002). "The characterization of upper-room ultraviolet germicidal irradiation in inactivating airborne microorganisms". Environmental Health Perspectives. 101 (1): 95–101. doi:10.1289/ehp.0211095. PMC 1240698. PMID 11781170.

- ↑ "Environmental Analysis of Indoor Air Pollution" (PDF). CaluTech UV Air. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

- ↑ Harm, W., 1980, Biological Effects of Ultraviolet Radiation, International Union of Pure and Applied Biophysics, Biophysics series, Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ "Catskill-Delaware Water Ultraviolet Disinfection Facility". New York City Department of Environmental Protection (NYCDEP). Archived from the original on September 6, 2012.

- ↑ "NYC Catskill-Delaware UV Facility Opening Ceremony". London, ON: Trojan Technologies. Archived from the original on 2015-06-13.

- ↑ Ware, M. W.; et al. "Inactivation of Giardia muris by low pressure ultraviolet light" (PDF). EPA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ "Household UV disinfection: A sustainable option - UV-Tube".

- ↑ "Chip packets help make safer water in Papua New Guinea".

- ↑ "Drinking water quality". Water, sanitation and health. WHO. Archived from the original on 2008-10-02.

- ↑ "UV sterilization; aquarium and pond". American Aquarium Products.

- ↑ Wolfe, R.L. (1990). "Ultraviolet disinfection of potable water". Environmental Science & Technology. 24 (6): 768–773. Bibcode:1990EnST...24..768W. doi:10.1021/es00076a001.

- 1 2 Hessling, Martin; Gross, Andrej; Hoenes, Katharina; Rath, Monika; Stangl, Felix; Tritschler, Hanna; Sift, Michael (2016-01-27). "Efficient Disinfection of Tap and Surface Water with Single High Power 285 nm LED and Square Quartz Tube". Photonics. 3 (1): 7. doi:10.3390/photonics3010007.

- ↑ "Treatment technology report for recycled water" (PDF). California Division of Drinking Water and Environmental Management. January 2007. p. . Retrieved 30 January 2011.

External links

| Look up sanitation in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |