Receptive aphasia

| Receptive aphasia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Wernicke's aphasia, fluent aphasia, sensory aphasia |

| |

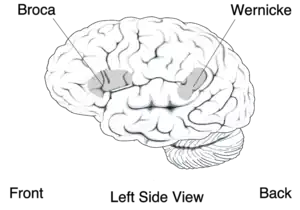

| Broca's area and Wernicke's area | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Wernicke's aphasia, also known as receptive aphasia,[1] sensory aphasia or posterior aphasia, is a type of aphasia in which individuals have difficulty understanding written and spoken language.[2] Patients with Wernicke's aphasia demonstrate fluent speech, which is characterized by typical speech rate, intact syntactic abilities and effortless speech output.[3] Writing often reflects speech in that it tends to lack content or meaning. In most cases, motor deficits (i.e. hemiparesis) do not occur in individuals with Wernicke's aphasia.[4] Therefore, they may produce a large amount of speech without much meaning. Individuals with Wernicke's aphasia are typically unaware of their errors in speech and do not realize their speech may lack meaning.[5] They typically remain unaware of even their most profound language deficits.

Like many acquired language disorders, Wernicke's aphasia can be experienced in many different ways and to many different degrees. Patients diagnosed with Wernicke's aphasia can show severe language comprehension deficits; however, this is dependent on the severity and extent of the lesion.[2] Severity levels may range from being unable to understand even the simplest spoken and/or written information to missing minor details of a conversation.[2] Many diagnosed with Wernicke's aphasia have difficulty with repetition in words and sentences and/or working memory.[5]

Wernicke's aphasia was named after German physician Carl Wernicke, who is credited with discovering the area of the brain responsible for language comprehension (Wernicke's area).[6]

Signs and symptoms

The following are common symptoms seen in patients with Wernicke's aphasia:

- Impaired comprehension: deficits in understanding (receptive) written and spoken language.[2] This is because Wernicke's area is responsible for assigning meaning to the language that is heard, so if it is damaged, the brain cannot comprehend the information that is being received.

- Poor word retrieval: ability to retrieve target words is impaired.[2] This is also referred to as anomia.

- Fluent speech: individuals with Wernicke's aphasia do not have difficulty with producing connected speech that flows.[6] Although the connection of the words may be appropriate, the words they are using may not belong together or make sense (see Production of jargon below).[7]

- Production of jargon: speech that lacks content, consists of typical intonation, and is structurally intact.[8] Jargon can consist of a string of neologisms, as well as a combination of real words that do not make sense together in context. The jargon may include word salads.

- Awareness: Individuals with Wernicke's aphasia are often not aware of their incorrect productions, which would further explain why they do not correct themselves when they produce jargon, paraphasias, or neologisms.[9]

- Paraphasias:[2][3]

- Phonemic (literal) paraphasias: involves the substitution, addition, or rearrangement of sounds so that an error can be defined as sounding like the target word. Often, half of the word is still intact which allows for easy comparison to the appropriate, original word.

- E.g. "bap" for "map"

- Semantic (verbal) paraphasias: saying a word that is related to the target word in meaning or category; frequently observed in Wernicke's aphasia.

- E.g. "jet" for "airplane" or "knife" for "fork"

- Phonemic (literal) paraphasias: involves the substitution, addition, or rearrangement of sounds so that an error can be defined as sounding like the target word. Often, half of the word is still intact which allows for easy comparison to the appropriate, original word.

- Neologisms: nonwords that have no relation to the target word.[2]

- E.g. "dorflur" for "shoe"

- Circumlocution: talking around the target word.[2]

- E.g. "uhhh it's white... it's flat... you write on it..." (when referencing paper)

- Press of speech: run-on speech.[2]

- If a clinician asks, "what do you do at a supermarket?" And the individual responds with "Well, the supermarket is a place. It is a place with a lot of food. My favorite food is Italian food. At a supermarket, I buy different kinds of food. There are carts and baskets. Supermarkets have lots of customers, and workers..."

- Lack of hemiparesis: typically, no motor deficits are seen with a localized lesion in Wernicke's area.[4]

- Reduced retention span: reduced ability to retain information for extended periods of time.[2]

- Impairments in reading and writing: impairments can be seen in both reading and writing with differing severity levels.[6]

How to differentiate from other types of aphasia[2]

- Expressive aphasia (non-fluent Broca's aphasia): individuals have great difficulty forming complete sentences with generally only basic content words (leaving out words like "is" and "the").

- Global aphasia: individuals have extreme difficulties with both expressive (producing language) and receptive (understanding language).

- Anomic aphasia: the biggest hallmark is one's poor word-finding abilities; one's speech is fluent and appropriate, but full of circumlocutions (evident in both writing and speech).

- Conduction aphasia: individuals can comprehend what is being said and are fluent in spontaneous speech, but they cannot repeat what is being said to them.

Causes

The most common cause of Wernicke's aphasia is stroke. Strokes may occur when blood flow to the brain is completely interrupted or severely reduced. This has a direct effect on the amount of oxygen and nutrients being able to supply the brain, which causes brain cells to die within minutes.[10]

"The middle cerebral arteries supply blood to the cortical areas involved in speech, language and swallowing. The left middle cerebral artery provides Broca's area, Wernicke's area, Heschl's gyrus, and the angular gyrus with blood".[11] Therefore, in patients with Wernicke's aphasia, there is typically an occlusion to the left middle cerebral artery.

As a result of the occlusion in the left middle cerebral artery, Wernicke's aphasia is most commonly caused by a lesion in the posterior superior temporal gyrus (Wernicke's area).[2] This area is posterior to the primary auditory cortex (PAC) which is responsible for decoding individual speech sounds. Wernicke's primary responsibility is to assign meaning to these speech sounds. The extent of the lesion will determine the severity of the patients deficits related to language. Damage to the surrounding areas (perisylvian region) may also result in Wernicke's aphasia symptoms due to variation in individual neuroanatomical structure and any co-occurring damage in adjacent areas of the brain.[2]

Diagnosis

Aphasia is usually first recognized by the physician who treats the person for his or her brain injury. Most individuals will undergo a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scan to confirm the presence of a brain injury and to identify its precise location.[12] In circumstances where a person is showing possible signs of aphasia, the physician will refer him or her to a speech-language pathologist (SLP) for a comprehensive speech and language evaluation. SLPs will examine the individual's ability to express him or herself through speech, understand language in written and spoken forms, write independently, and perform socially.[12]

The American Speech, Language, Hearing Association (ASHA) states a comprehensive assessment should be conducted in order to analyze the patient's communication functioning on multiple levels; as well as the effect of possible communication deficits on activities of daily living. Typical components of an aphasia assessment include: case history, self report, oral-motor examination, language skills, identification of environmental and personal factors, and the assessment results. A comprehensive aphasia assessment includes both formal and informal measures.[13]

Formal assessments include:

- Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (BDAE): diagnoses the presence and type of aphasia, focusing on location of lesion and the underlying linguistic processes.[14]

- Western Aphasia Battery – Revised (WAB): determines the presence, severity, and type of aphasia; and can also determine baseline abilities of patient.[15]

- Communication Activities of Daily Living - Second Edition (CADL-2): measures functional communication abilities; focuses on reading, writing, social interactions, and varying levels of communication.[16]

- Revised Token Test (RTT): assess receptive language and auditory comprehension; focuses on patient's ability to follow directions.[17]

Informal assessments, which aid in the diagnosis of patients with suspected aphasia, include:[18]

- Conversational speech and language sample[18]

- Family interview[18]

- Case history or medical chart review[18]

- Behavioral observations[18]

Diagnostic information should be scored and analyzed appropriately. Treatment plans and individual goals should be developed based on diagnostic information, as well as patient and caregiver needs, desires, and priorities.[13]

Treatment

According to Bates et al. (2005), "the primary goal of rehabilitation is to prevent complications, minimize impairments, and maximize function". The topics of intensity and timing of intervention are widely debated across various fields.[19] Results are contradictory: some studies indicate better outcomes with early intervention,[20] while other studies indicate starting therapy too early may be detrimental to the patient's recovery.[21] Recent research suggests, that therapy be functional and focus on communication goals that are appropriate for the patient's individual lifestyle.[22]

Specific treatment considerations for working with individuals with Wernicke's aphasia (or those who exhibit deficits in auditory comprehension) include using familiar materials, using shorter and slower utterances when speaking, giving direct instructions, and using repetition as needed.[2]

Role of neuroplasticity in recovery

Neuroplasticity is defined as the brain's ability to reorganize itself, lay new pathways, and rearrange existing ones, as a result of experience.[23] Neuronal changes after damage to the brain such as collateral sprouting, increased activation of the homologous areas, and map extension demonstrate the brain's neuroplastic abilities. According to Thomson, "Portions of the right hemisphere, extended left brain sites, or both have been shown to be recruited to perform language functions after brain damage.[24] All of the neuronal changes recruit areas not originally or directly responsible for large portions of linguistic processing.[25] Principles of neuroplasticity have been proven effective in neurorehabilitation after damage to the brain. These principles include: incorporating multiple modalities into treatment to create stronger neural connections, using stimuli that evoke positive emotion, linking concepts with simultaneous and related presentations, and finding the appropriate intensity and duration of treatment for each individual patient.[23]

Auditory comprehension treatment

Auditory comprehension is a primary focus in treatment for Wernicke's aphasia, as it is the main deficit related to this diagnosis. Therapy activities may include:

- Single-word comprehension: A common treatment method used to support single-word comprehension skills is known as a pointing drill. Through this method, clinicians lay out a variety of images in front of a patient. The patient is asked to point to the image that corresponds to the word provided by the clinician.[2]

- Understanding spoken sentences: "Treatment to improve comprehension of spoken sentences typically consists of drills in which patients answer questions, follow directions or verify the meaning of sentences".[2]

- Understanding conversation: An effective treatment method to support comprehension of discourse includes providing a patient with a conversational sample and asking him or her questions about that sample. Individuals with less severe deficits in auditory comprehension may also be able to retell aspects of the conversation.[2]

Word retrieval

Anomia is consistently seen in aphasia, so many treatment techniques aim to help patients with word finding problems. One example of a semantic approach is referred to as semantic feature analyses. The process includes naming the target object shown in the picture and producing words that are semantically related to the target. Through production of semantically similar features, participants develop more skilled in naming stimuli due to the increase in lexical activation.[26]

Restorative therapy approach

Neuroplasticity is a central component to restorative therapy to compensate for brain damage. This approach is especially useful in Wernicke's aphasia patients that have suffered from a stroke to the left brain hemisphere.[27]

Schuell's stimulation approach is a main method in traditional aphasia therapy that follows principles to retrieve function in the auditory modality of language and influence surrounding regions through stimulation. The guidelines to have the most effective stimulation are as follows: Auditory stimulation of language should be intensive and always present when other language modalities are stimulated.[27]

- The stimulus should be presented at a difficulty level equal to or just below the patient's ability.

- Sensory stimulation must be present and repeated throughout the treatment.

- Each stimulus applied should produce a response; if there is no response more stimulation cues should be provided.

- Response to stimuli should be maximized to create more opportunities for success and feedback for the speech-language pathologist.

- The feedback of the speech-language pathologist should promote further success and patient and encouragement.

- Therapy should follow an intensive and systemic method to create success by progressing in difficulty.

- Therapies should be varied and build off of mastered therapy tasks.[27]

Schuell's stimulation utilizes stimulation through therapy tasks beginning at a simplified task and progressing to become more difficult including:

- Point to tasks. During these tasks the patient is directed to point to an object or multiple objects. As the skill is learned the level of complexity increases by increasing the number of objects the patient must point to.[27]

- Simple: "Point to the book."

- Complex: "Point to the book and then to the ceiling after touching your ear."

- Following directions with objects. During these tasks the patient is instructed to follow the instruction of manually following directions that increase in complexity as the skill is learned.[27]

- Simple: "Pick up the book."

- Complex: "Pick up the book and put it down on the bench after I move the cup."

- Yes or no questions – This task requires the patient to respond to various yes or no questions that can range from simple to complex.[27]

- Paraphrasing and retelling – This task requires the patient to read a paragraph and, afterwards, paraphrase it aloud. This is the most complex of Schuell's stimulation tasks because it requires comprehension, recall, and communication.[27]

Social approach to treatment

The social approach involves a collaborative effort on behalf of patients and clinicians to determine goals and outcomes for therapy that could improve the patient's quality of life. A conversational approach is thought to provide opportunities for development and the use of strategies to overcome barriers to communication. The main goals of this treatment method are to improve the patient's conversational confidence and skills in natural contexts using conversational coaching, supported conversations, and partner training.[28]

- Conversational coaching involves patients with aphasia and their speech language pathologists, who serve as a "coach" discussing strategies to approach various communicative scenarios. The "coach" will help the patient develop a script for a scenario (such as ordering food at a restaurant), and help the patient practice and perform the scenario in and out of the clinic while evaluating the outcome.[29]

- Supported conversation also involves using a communicative partner who supports the patient's learning by providing contextual cues, slowing their own rate of speech, and increasing their message's redundancy to promote the patient's comprehension.[29]

Additionally, it is important to include the families of patients with aphasia in treatment programs. Clinicians can teach family members how to support one another, and how to adjust their speaking patterns to facilitate their loved one's treatment and rehabilitation.[28]

Prognosis

Prognosis is strongly dependent on the location and extent of the lesion (damage) to the brain. Many personal factors also influence how a person will recover, which include age, previous medical history, level of education, gender, and motivation.[24] All of these factors influence the brain's ability to adapt to change, restore previous skills, and learn new skills. It is important to remember that all the presentations of Receptive Aphasia may vary. The presentation of symptoms and prognosis are both dependent on personal components related to the individual's neural organization before the stroke, the extent of the damage, and the influence of environmental and behavioral factors after the damage occurs.[30] The quicker a diagnosis of a stroke is made by a medical team, the more positive the patient's recovery may be. A medical team will work to control the signs and symptoms of the stroke and rehabilitation therapy will begin to manage and recover lost skills. The rehabilitation team may consist of a certified speech-language pathologist, physical therapist, occupational therapist, and the family or caregivers.[19] The length of therapy will be different for everyone, but research suggests that intense therapy over a short amount of time can improve outcomes of speech and language therapy for patients with aphasia. Research is not suggesting the only way therapy should be administered, but gives insight on how therapy affects the patient's prognosis.[21]

See also

References

- ↑ Nakai, Y; Jeong, JW; Brown, EC; Rothermel, R; Kojima, K; Kambara, T; Shah, A; Mittal, S; Sood, S; Asano, E (2017). "Three- and four-dimensional mapping of speech and language in patients with epilepsy". Brain. 140 (5): 1351–1370. doi:10.1093/brain/awx051. PMC 5405238. PMID 28334963.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Brookshire, Robert (2007). Introduction to neurogenic communication disorders (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

- 1 2 Damasio, A.R. (1992). "Aphasia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 326 (8): 531–539. doi:10.1056/nejm199202203260806. PMID 1732792.

- 1 2 Murdoch, B.E. (1990). Acquired Speech and Language Disorders: A Neuroanatomical and Functional Neurological Approach. Baltimore, MD: Chapman and Hall. pp. 73–76.

- 1 2 "Common Classifications of Aphasia". American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

- 1 2 3 "Wernicke's (Receptive) Aphasia". National Aphasia Association.

- ↑ "Types of Aphasia". American Stroke Association.

- ↑ "ASHA Glossary". American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

- ↑ "Aphasia Definitions". National Aphasia Association.

- ↑ "Stroke". Mayo Clinic. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ↑ McCaffrey, P. "Medical aspects: Blood supply in the brain".

- 1 2 "Aphasia". National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD).

- 1 2 "Aphasia: Roles and responsibilities". American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

- ↑ Goodglass, H.; Kaplan, E.; Barresi, B. (2001). Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination. Austin, TX: PRO-ED, Inc.

- ↑ Kereesz, A. (2006). Western Aphasia Battery. San Antonio, TX: Pearson.

- ↑ Holland, A.L.; Fromm, D.; Wozniak, L. (2018). Communication Activities in Daily Living (CADL-3) (3rd ed.). Alberta, Canada: Brijan Resources.

- ↑ McNeil, M.M.; Prescott, T.E. (1978). Revised Token Test. Austin, TX: PRO-ED, Inc.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Assessment Tools, Techniques, and Data Sources". American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

- 1 2 Bates, B.; Choi, J.; Duncan, P.W.; Glasberg, J.J.; Graham, G.D.; Katz, R.C....; Zorowitz, R. (2005). "Veterans affairs/department of defense clinical practice guideline for the management of adult stroke rehabilitation care". Stroke. 36 (9): 2049–2056. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000180432.73724.AD. PMID 16120847.

- ↑ Bhogal, S.K.; Teasell, R.; Speechley, M. (2003). "Intensity of aphasia therapy, impact on recovery". Stroke. 34 (4): 987–993. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000062343.64383.D0. PMID 12649521.

- 1 2 Nouwens, F.; Visch-Brink, E.G.; Van de Sandt-Koenderman, M.M.E.; Dippeo, D.W.J; Kaudstaal, P.J.; de Law, L.M.L. (2015). "Optimal timing for speech and language therapy after stroke: More evidence needed". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 15 (8): 885–893. doi:10.1586/14737175.2015.1058161. PMID 26088694.

- ↑ "Life Participation Approach to Aphasia: A Statement of Values for the Future". American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

- 1 2 Bayles, K.A.; Tomodea, C.K. (2010). "Neuroplasticity: Implications for treating cognitive communication disorders". ASHA National Convention.

- 1 2 Thomson, C.K. (2000). "Neuroplasticity: Evidence from aphasia". Journal of Communication Disorders. 33 (4): 357–366. doi:10.1016/S0021-9924(00)00031-9. PMC 3086401. PMID 11001162.

- ↑ Raymer, A.M.; Beeson, P.; Holland, A.; Kendall, D.; Maher, L.M.; Martin, M.; Gonzolez Rothi, L.J. (2008). "Transitional research in aphasia: From neuroscience to neurorehabilitation". Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 51: 259–275.

- ↑ Boyle, M.; Coelho, C.A. (2004). "Semantic feature analysis treatment for anomia in two fluent aphasia syndromes". American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 13 (3): 236–249. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2004/025). PMID 15339233.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Manasco, H. (2021). Introduction to neurogenic communication disorders. Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- 1 2 LaPointe, L. (2005). Aphasia and Related Neurogenic Language Disorders (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers Inc.

- 1 2 Davis, G.A. "Aphasia Therapy Guide". National Aphasia Association.

- ↑ Keefe, K.A. (1995). "Applying basic neuroscience to aphasia therapy: What the animals are telling us". American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 4 (4): 88–93. doi:10.1044/1058-0360.0404.88.

Further reading

- Klein, Stephen B., and Thorne. Biological Psychology. New York: Worth, 2007. Print.

- Saladin, Kenneth S. Anatomy & Physiology: the Unity of Form and Function. New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2010. Print.