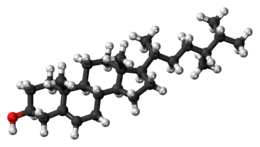

Campesterol

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

(1R,3aS,3bS,7S,9aR,9bS,11aR)-1-[(2R,5R)-5,6-Dimethylheptan-2-yl]-9a,11a-dimethyl-2,3,3a,3b,4,6,7,8,9,9a,9b,10,11,11a-tetradecahydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-7-ol | |

| Other names

Campest-5-en-3β-ol; (24R)-Ergost-5-en-3β-ol | |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number |

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.806 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula |

C28H48O |

| Molar mass | 400.691 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Campesterol is a phytosterol whose chemical structure is similar to that of cholesterol, and is one of the ingredients for E number E499.

Natural occurrences

Many vegetables, fruits, nuts,[1] and seeds contain campesterol, but in low concentrations. Banana, pomegranate, pepper, coffee, grapefruit, cucumber, onion, oat, potato, and lemon grass (citronella) are few examples of common sources containing campesterol at roughly 1–7 mg/100 g of the edible portion. In contrast, canola and corn oils contain as much as 16–100 mg/100 g. Levels are variable and are influenced by geography and growing environment. In addition, different strains have different levels of plant sterols. A number of new genetic strains are currently being engineered with the goal of producing varieties high in campesterol and other plant sterols.[2] It is also found in dandelion coffee.

It is so named because it was first isolated from the rapeseed (Brassica campestris).[3] It is thought to have anti-inflammatory effects. It was demonstrated that it inhibits several pro-inflammatory and matrix degradation mediators typically involved in osteoarthritis-induced cartilage degradation.[4]

Precursor of anabolic steroid boldenone

Being a steroid, campesterol is a precursor of anabolic steroid boldenone. Boldenone undecylenate is commonly used in veterinary medicine to induce growth in cattle, but it is also one of the most commonly abused anabolic steroids in sports. This led to suspicion that some athletes testing positive on boldenone undecylenate did not actually abuse the hormone itself, but consumed food rich in campesterol or similar phytosteroids.[5][6][7]

Cardiovascular disease

Plant sterols were first shown in the 1950s to be beneficial in lowering LDLs and cholesterol.[8] Since then, numerous studies have also reported the beneficial effects of the dietary intake of phytosterols, including campesterol.[9]

The campesterol molecules are thought to compete with cholesterol, thus reducing the absorption of cholesterol in the human intestine.[10] Plant sterols may also act directly on intestinal cells and affect transporter proteins. In addition, an effect on the synthesis of cholesterol-transporting proteins may occur in the liver cells through processes including cholesterol esterification and lipoprotein assembly, cholesterol synthesis, and apolipoprotein (apo) B100-containing lipoprotein removal.[11]

Serum levels of campesterol and the ratio of campesterol to cholesterol have been proposed as measures of cardiac risk. Some studies have suggested that higher levels predict lower cardiac risk. However, extremely high levels are thought to be indicative of higher risk, as indicated by genetic disorders such as sitosterolemia.[12] Study results of serum levels have been conflicting. A recent meta-analysis suggests that no clear relationship exists, and that perhaps previous studies have been confounded by other factors. For example, people who have a higher campesterol level related to a diet high in fruits and nuts may be consuming a Mediterranean-style diet, thus have lower risk because of other lipids or lifestyle factors. Intestinal absorption of cholesterol varies between individuals due to variations in the genes that encode for two proteins. The NPC1L1 protein which sits on the luminal side of the enterocyte is responsible for sterol absorption. Its counterpart, the ABCG5/G8 ATP Binding Cassette protein which also sits on the luminal side of the enterocyte, and on the bile canaliculi side of the hepatocyte, is responsible for sterol efflux. Variations in each of these proteins causes variation in absorption and efflux of dietary and biliary sterols - both cholesterol and plant sterols.[13]

Although studies in humans have shown that consumption of phytosterols may reduce LDL levels, evidence to recommend them as a treatment for hypercholesterolemia is insufficient. Larger trials are needed to provide such evidence, and are underway.[14] Animal studies have shown that campesterol and other phytosterols can reduce the size of atherogenic plaques, but no data yet show that consumption of phytosterols results in any clinical benefit such as a reduction in atherosclerosis, heart disease, cardiac events, or mortality.[15]

Adverse effects

Nutrient levels

Excessive supplementation with plant sterols may be associated with reductions in beta-carotene and lycopene levels.[15][16] Excessive long-term consumption of plant sterols might have a deleterious effect on vitamin E.[17]

Increased risk of disease

Excessive use of plant sterols has been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease,[10] and genetic conditions that cause extremely elevated levels of some phytosterols, such as sitosterol, are associated with higher risks of cardiovascular disease. However, this is an active area of debate, and no data suggest that modestly elevated levels of campesterol have a negative cardiac impact.[18]

References

- ↑ Segura, Ramon; Javierre, Casimiro; Lizarraga, M Antonia; Ros, Emilio (2007). "Other relevant components of nuts: Phytosterols, folate and minerals". British Journal of Nutrition. 96: S36–44. doi:10.1017/BJN20061862. PMID 17125532.

- ↑ Gül, Muhammet Kemal; Amar, Samija (2006). "Sterols and the phytosterol content in oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.)" (PDF). Journal of Cell and Molecular Biology. 5: 71–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-19. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

- ↑ Fernholz, Erhard; MacPhillamy, H. B. (1941). "Isolation of a New Phytosterol: Campesterol". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 63 (4): 1155. doi:10.1021/ja01849a079.

- ↑ Gabay, O.; Sanchez, C.; Salvat, C.; Chevy, F.; Breton, M.; Nourissat, G.; Wolf, C.; Jacques, C.; Berenbaum, F. (2010). "Stigmasterol: A phytosterol with potential anti-osteoarthritic properties". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 18 (1): 106–16. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2009.08.019. PMID 19786147.

- ↑ Boldenone, Boldione, and Milk Replacers in the Diet of Veal Calves: The Effects of Phytosterol Content on the Urinary Excretion of Boldenone Metabolites, G. Gallina, G. Ferretti, R. Merlanti, C. Civitareale, F. Capolongo, R. Draisci and C. Montesissa, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2007, 55 (20), pp 8275–8283

- ↑ Food Addit Contam. 2007 Jul;24(7):679-84.;Phytosterol consumption and the anabolic steroid boldenone in humans: a hypothesis piloted; Ros MM, Sterk SS, Verhagen H, Stalenhoef AF, de Jong N.;National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), the Netherlands.

- ↑ Excretion profile of boldenone in urine of veal calves fed two different milk replacers; R. Draisci, R. Merlanti, G. Ferretti, L. Fantozzi, C. Ferranti, F. Capolongo, S. Segato, C. Montesissa; Analytica Chimica Acta, Volume 586, Issues 1–2, 14 March 2007, Pages 171–176

- ↑ Farquhar, John W.; Sokolow, Maurice (1958). "Response of Serum Lipids and Lipoproteins of Man to Beta-Sitosterol and Safflower Oil". Circulation. 17 (5): 890–9. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.17.5.890. PMID 13537276.

- ↑ Heggen, E.; Granlund, L.; Pedersen, J.I.; Holme, I.; Ceglarek, U.; Thiery, J.; Kirkhus, B.; Tonstad, S. (2010). "Plant sterols from rapeseed and tall oils: Effects on lipids, fat-soluble vitamins and plant sterol concentrations". Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 20 (4): 258–65. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2009.04.001. hdl:10852/55512. PMID 19748247.

- 1 2 Choudhary, SP; Tran, LS (2011). "Phytosterols: Perspectives in human nutrition and clinical therapy". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 18 (29): 4557–67. doi:10.2174/092986711797287593. PMID 21864283.

- ↑ Calpe-Berdiel, Laura; Escolà-Gil, Joan Carles; Blanco-Vaca, Francisco (2009). "New insights into the molecular actions of plant sterols and stanols in cholesterol metabolism". Atherosclerosis. 203 (1): 18–31. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.06.026. PMID 18692849.

- ↑ Tsubakio-Yamamoto, Kazumi; Nishida, Makoto; Nakagawa-Toyama, Yumiko; Masuda, Daisaku; Ohama, Tohru; Yamashita, Shizuya (2010). "Current Therapy for Patients with Sitosterolemia –Effect of Ezetimibe on Plant Sterol Metabolism". Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis. 17 (9): 891–900. doi:10.5551/jat.4614. PMID 20543520.

- ↑ Helgadottir, Anna; Thorleifsson, Gudmar; Alexandersson, Kristjan F.; Tragante, Vinicius; Thorsteinsdottir, Margret; Eiriksson, Finnur F.; Gretarsdottir, Solveig; Björnsson, Eythór; Magnusson, Olafur; Sveinbjornsson, Gardar; Jonsdottir, Ingileif (2020-07-21). "Genetic variability in the absorption of dietary sterols affects the risk of coronary artery disease". European Heart Journal. 41 (28): 2618–2628. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa531. ISSN 0195-668X. PMC 7377579.

- ↑ Párraga, Ignacio; López-Torres, Jesús; Andrés, Fernando; Navarro, Beatriz; Del Campo, José M; García-Reyes, Mercedes; Galdón, María P; Lloret, Ángeles; Precioso, Juan C; Rabanales, Joseba (2011). "Effect of plant sterols on the lipid profile of patients with hypercholesterolaemia. Randomised, experimental study". BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 11: 73. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-11-73. PMC 3180270. PMID 21910898.

- 1 2 Clifton, Peter (2009). "Lowering cholesterol – A review on the role of plant sterols". Australian Family Physician. 38 (4): 218–21. PMID 19350071.

- ↑ Richelle, Myriam; Enslen, Marc; Hager, Corinne; Groux, Michel; Tavazzi, Isabelle; Godin, Jean-Philippe; Berger, Alvin; Métairon, Sylviane; et al. (2004). "Both free and esterified plant sterols reduce cholesterol absorption and the bioavailability of β-carotene and α-tocopherol in normocholesterolemic humans". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 80 (1): 171–7. doi:10.1093/ajcn/80.1.171. PMID 15213045.

- ↑ Tuomilehto, J; Tikkanen, M J; Högström, P; Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, S; Piironen, V; Toivo, J; Salonen, J T; Nyyssönen, K; et al. (2008). "Safety assessment of common foods enriched with natural nonesterified plant sterols". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 63 (5): 684–91. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2008.11. PMID 18270526.

- ↑ Calpe-Berdiel, L; Méndez-González, J; Blanco-Vaca, F; Carles Escolà-Gil, J (2009). "Increased plasma levels of plant sterols and atherosclerosis: A controversial issue". Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 11 (5): 391–8. doi:10.1007/s11883-009-0059-x. PMID 19664384.