Diplococcus

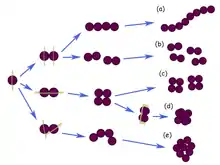

A diplococcus (plural diplococci) is a round bacterium (a coccus) that typically occurs in the form of two joined cells.

Types

Examples of gram-negative diplococci are Neisseria spp. and Moraxella catarrhalis. Examples of gram-positive diplococci are Streptococcus pneumoniae and Enterococcus spp.[1][2] Presumably, diplococcus has been implicated in encephalitis lethargica.[3]

Taxonomy

Gram-negative diplococci

Neisseria spp.

Phylum: Proteobacteria

Class: Betaproteobacteria

Order: Neisseriales

Family: Neisseriaceae

Genus: Neisseria

The genus Neisseria belongs to the family Neisseriaceae. This genus, Neisseria, is divided into more than ten different species, but most of them are gram negative and coccoid. The gram-negative, coccoid species include: Neisseria cinerea, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Neisseria polysaccharea, Neisseria lactamica, Neisseria meningitidis, Neisseria mucosa, Neisseria oralis and Neisseria subflava. Of these Neisseria species, the most common, pathogenic species are N. meningitidis and N.gonorrhoeae.[4]

Moraxella catarrhalis

Phylum: Proteobacteria

Class: Gammaproteobacteria

Order: Pseudomonadales

Family: Moraxellaceae

Genus: Moraxella

The genus Moraxella belongs to the family Moraxellaceae. This genus, Moraxellaceae, comprises gram-negative coccobacilli bacteria: Moraxella lacunata, Moraxella atlantae, Moraxella boevrei, Moraxella bovis, Moraxella canis, Moraxella caprae, Moraxella caviae, Moraxella cuniculi, Moraxella equi, Moraxella lincolnii, Moraxella nonliquefaciens, Moraxella osloensis, Moraxella ovis and Moraxella saccharolytica, Moraxella pluranimalium.[5] However, only one has a morphology of diplococcus, Moraxella catarrhalis. M. catarrhalis is a salient pathogen contributing to infections in the human body.[6]

Gram-positive diplococci

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Phylum: Firmicutes

Class: Bacilli

Order: Lactobacillales

Family: Streptococcaceae

Genus: Streptococcus

Species: Streptococcus pneumoniae

The species Streptococcus pneumoniae belongs to the genus Streptococcus and the family Streptococcaceae. The genus Streptococcus has around 129 species and 23 subspecies[7] that benefit many microbiomes on the human body. There are many species that show non-pathogenic characteristics; however, there are some, like S. pneumoniae, that exhibit pathogenic characteristics in the human body.[8][2]

Enterococcus spp.

Phylum: Firmicutes

Class: Bacilli

Order: Lactobacillales

Family: Enterococcaceae

Genus: Enterococcus

The genus Enterococcus belongs to the family Enterococcaceae. This genus is divided into 58 species and two subspecies.[9] These gram-positive, coccoid bacteria were once thought to be harmless to the human body. However, within the last ten years, there has been an influx of nosocomial pathogens originating from Enterococcus bacteria.[10][2]

Pathogenicity

Many of these diplococci bacteria have species (strains) exhibit pathogenic characteristics. Examples of gram-negative, diplococci pathogens would be N.gonorrhoeae and N. meningitidis.[4] N. gonorrhea is transmitted through copulation with a person who is infected.[11] This bacterium embeds in the reproductive tract tissue in women, causing cervical and uterine infections.[11][12] Once the membranous tissues within the fallopian tubes are infected, complications in pregnancies will arise. In men, this bacterium infects the urethra. Testing on male subjects, showed apparent bacteria forming colonies within the epithelium and exhibiting signs of damage in these cells.[12] N. meningitidis, also known as meningococcus, can cause bacterial infections on/in the body, i.e. lungs, nasopharynx, or skin, which eventually enters the bloodstream. (web arch) The malignant bacteria within the bloodstream burgeon and often ends in fatality if extreme enough.[13][14] Another example of a gram-negative, diplococci pathogen is Moraxella catarrhalis. A study of M. catarrhalis was conducted on 58 cases and all presented similar, yet different results. Many cases appeared to have infections within the body: pharyngitis, tracheitis, sinusitis, bronchitis, and otitis. Few showed characteristics of meningitis, endocarditis, and septic arthritis.[15]

Examples of gram-positive, diplococci pathogens include Streptococcus pneumoniae and some species in Enterococcus bacteria. Streptococcus pneumoniae infects the human anatomy in the respiratory tract and the immune system. This bacteria congregates at the end of the bronchial tubes in the alveoli, which elicits an inflammatory results. Then, this elicited response fills with blood and all its components fill the alveoli; resulting in pneumonia.[16] Enterococcus has given rise to Entercoccal meningitis, an uncommon nosocomial disease. These nosocomial infections also affect the urinary tract and post-surgical wounds, still healing.[17]

References

- ↑ Richard A. Harvey (Ph.D.) (2007). Microbiology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 395–. ISBN 978-0-7817-8215-9.

- 1 2 3 Gillespie, Claire (August 20, 2018). "Types of Coccus Bacteria". Sciencing. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- ↑ "Mystery of the forgotten plague". 2004-07-27.

- 1 2 "Neisseria Trevisan, 1885". www.gbif.org. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ↑ "Moraxella". LPSN. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ↑ Verhaegh, S.J.C. (Suzanne) (2011-06-01). Epidemiology and pathogenesis of Moraxella catarrhalis colonization and infection. ISBN 9780397515684. OCLC 929980928.

- ↑ "Streptococcus". LPSN. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ↑ "Streptococcus pneumoniae (Klein, 1884) Chester, 1901". www.gbif.org. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ↑ "Enterococcus". LPSN. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ↑ Fisher, Katie; Phillips, Carol (2009). "The ecology, epidemiology and virulence of Enterococcus". Microbiology. 155 (6): 1749–1757. doi:10.1099/mic.0.026385-0. ISSN 1350-0872. PMID 19383684.

- 1 2 "Detailed STD Facts - Gonorrhea". www.cdc.gov. 2019-11-12. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- 1 2 Arvidson, Cindy Grove; Kirkpatrick, Risa; Witkamp, Manon T.; Larson, Jason A.; Schipper, Christel A.; Waldbeser, Lillian S.; O’Gaora, Peadar; Cooper, Morris; So, Magdalene (1999-02). "Neisseria gonorrhoeae Mutants Altered in Toxicity to Human Fallopian Tubes and Molecular Characterization of the Genetic Locus Involved". Infection and Immunity. 67 (2): 643–652. ISSN 0019-9567. PMID 9916071; 2019-12-01

- ↑ Rouphael, Nadine G.; Stephens, David S. (2012). "Neisseria meningitidis: Biology, Microbiology, and Epidemiology". Neisseria meningitidis. Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.J.). Vol. 799. pp. 1–20. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-346-2_1. ISBN 978-1-61779-345-5. ISSN 1064-3745. PMC 4349422. PMID 21993636.

- ↑ "Neisseria Meningitidis". 2009-11-10. Archived from the original on 2009-11-10. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ↑ Ioannidis, John P. A.; Worthington, Michael; Griffiths, Jeffrey K.; Snydman, David R. (1995). "Spectrum and Significance of Bacteremia Due to Moraxella catarrhalis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 21 (2): 390–397. doi:10.1093/clinids/21.2.390. ISSN 1058-4838. JSTOR 4458794. PMID 8562749.

- ↑ Anderson, Cindy. "Pathogenic Properties (Virulence Factors) of Some Common Pathogens" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- ↑ Guardado, Rodríguez; Asensi, V.; Torres, J. M.; Pérez, F.; Blanco, A.; Maradona, J. A.; Cartón, J. A. (2006–2008). "Post surgical entercoccal meningitis: Clinical and epidemiological study of 20 cases". Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 38 (8): 584–588. doi:10.1080/00365540600606416. PMID 16857599. S2CID 24189202.