Necrolytic migratory erythema

| Necrolytic migratory erythema | |

|---|---|

| Other names: NME | |

| |

| Necrolytic migratory erythema in the gluteal area | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

Necrolytic migratory erythema is a red, blistering rash that spreads across the skin. It particularly affects the skin around the mouth and distal extremities; but may also be found on the lower abdomen, buttocks, perineum, and groin. It is strongly associated with glucagonoma, a glucagon-producing tumor of the pancreas, but is also seen in a number of other conditions including liver disease and intestinal malabsorption.[1]

Signs and symptoms

NME features a characteristic skin eruption of red patches with irregular borders, intact and ruptured vesicles, and crust formation.[2] It commonly affects the limbs and skin surrounding the lips, although less commonly the abdomen, perineum, thighs, buttocks, and groin may be affected.[2] Frequently these areas may be left dry or fissured as a result.[2] All stages of lesion development may be observed synchronously.[3] The initial eruption may be exacerbated by pressure or trauma to the affected areas.[2]

.jpg.webp) Necrolytic migratory erythema

Necrolytic migratory erythema.jpg.webp) Necrolytic migratory erythema

Necrolytic migratory erythema.jpg.webp) Necrolytic migratory erythema

Necrolytic migratory erythema

Associated conditions

William Becker first described an association between NME and glucagonoma in 1942[3][4] and since then, NME has been described in as many as 70% of persons with a glucagonoma.[5] NME is considered part of the glucagonoma syndrome,[6] which is associated with hyperglucagonemia, diabetes mellitus, and hypoaminoacidemia.[3] When NME is identified in the absence of a glucagonoma, it may be considered "pseudoglucagonoma syndrome".[7] Less common than NME with glucagonoma, pseudoglucagonoma syndrome may occur in a number of systemic disorders:[8]

- Celiac disease

- Ulcerative colitis

- Crohn's disease

- Hepatic cirrhosis

- Hepatocellular carcinoma

- Lung cancer, including small cell lung cancer

- Tumors that secrete insulin- or insulin-like growth factor 2

- Duodenal cancer

Cause

The cause of NME is unknown, although various mechanisms have been suggested. These include hyperglucagonemia, zinc deficiency, fatty acid deficiency, hypoaminoacidemia, and liver disease.[3]

Mechanism

The pathogenesis is also unknown, though it is recognized that hyperglucagonemia has a role in the pathophysiology, though undetermined as yet[1]

Diagnosis

In terms of the diagnosis of this dermatological condition, skin biopsies should be performed, as well as, physical exam, lab tests (glucagon level), imaging of abdomen and several other tests.[1]

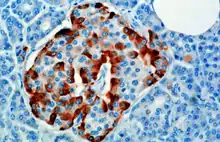

Histology

The histopathologic features of NME include:[9]

- Epidermal necrosis

- Subcorneal pustules

- Suppurative folliculitis

The vacuolated, pale, swollen epidermal cells and necrosis of the superficial epidermis are most characteristic.[3] Immunofluorescence is usually negative.[3]

Management

Managing the original condition, glucagonoma, by octreotide or surgery. After resection, the rash typically resolves within days.[10]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Foss, Michael G.; Ferrer-Bruker, Sarah J. (2021). "Necrolytic Migratory Erythema". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP (2009). "Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy". CA – A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 59 (2): 73–98. doi:10.3322/caac.20005. PMID 19258446.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Pujol RM, Wang CY, el-Azhary RA, Su WP, Gibson LE, Schroeter AL (January 2004). "Necrolytic migratory erythema: clinicopathologic study of 13 cases". International Journal of Dermatology. 43 (1): 12–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01844.x. PMID 14693015.

- ↑ Becker WS, Kahn D, Rothman S (1942). "Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignant tumors". Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology. 45 (6): 1069–1080. doi:10.1001/archderm.1942.01500120037004.

- ↑ van Beek AP, de Haas ER, van Vloten WA, Lips CJ, Roijers JF, Canninga-van Dijk MR (November 2004). "The glucagonoma syndrome and necrolytic migratory erythema: a clinical review". Eur. J. Endocrinol. 151 (5): 531–7. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1510531. PMID 15538929.

- ↑ Odom, Richard B.; Davidsohn, Israel; James, William D.; Henry, John Bernard; Berger, Timothy G.; Clinical diagnosis by laboratory methods; Dirk M. Elston (2006). Andrews' diseases of the skin: clinical dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. pp. 143. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- ↑ Echenique-Elizondo, Miguel; Tuneu Valls, Ana; Elorza Orúe, José L.; Martinez de Lizarduy, Ignacio; Ibáñez Aguirre, Javier (July 2004). "Glucagonoma and pseudoglucagonoma syndrome". JOP: Journal of the pancreas. 5 (4): 179–185. ISSN 1590-8577. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ↑ Mignogna MD, Fortuna G, Satriano AR (December 2008). "Small-cell lung cancer and necrolytic migratory erythema". The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (25): 2731–2. doi:10.1056/NEJMc0805992. PMID 19092164.

- ↑ Patterson, James W. (19 November 2019). Weedon's Skin Pathology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 603. ISBN 978-0-7020-7583-4. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ↑ Compton, Nicholas L.; Chien, Andy J. (May 2013). "A Rare but Revealing Sign: Necrolytic Migratory Erythema". The American Journal of Medicine. 126 (5): 387–389. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.01.012. PMID 23477490.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |