Émile Storms

Émile Pierre Joseph Storms (2 June 1846 – 12 January 1918) was a Belgian soldier, explorer, and official for the Congo Free State. He is known for his work between 1882 and 1885 in establishing a European presence in the regions around Lake Tanganyika, during which he supported the White Fathers missionaries and attempted to suppress the East African slave trade. He is remembered for his ruthless fight against slavery and the capture and subsequent execution of the slave trader Lusinga.

Émile Storms | |

|---|---|

Storms depicted in an 1886 engraving | |

| Born | 2 June 1846 Wetteren, East Flanders, Belgium |

| Died | 12 January 1918 (aged 71) Ixelles, Belgium |

| Nationality | Belgian |

| Occupation(s) | Soldier, Explorer |

| Known for | Founder of Mpala station, Congo |

Early years

Émile Pierre Joseph Storms was born at Wetteren, East Flanders in Belgium on 2 June 1846. On 11 December 1861 he joined the 5th Infantry Regiment. He was promoted to second-lieutenant in the 10th Regiment on 25 June 1870, and to Lieutenant in the 9th Regiment on 25 March 1876. He was admitted to the Belgium's military academy on 29 August 1878. He volunteered for the International African Association, and on 25 February 1882 was assigned to the Cartographic Institute. He was given the task of leading an expedition to explore the east coast of Africa.[1]

Expedition to Equatorial Africa

Outward journey

On 10 April 1882 Storms left Europe for Zanzibar. On his arrival his companion, Lieutenant Camille Constant of the grenadiers, fell ill and had to return to Europe. Storms learned that his contact, Guillaume Ramaeckers, had died at Karema on 25 February 1882. On 8 June 1882 Storms left the coast and marched via the mission of Tabora to Karema on the east coast of Lake Tanganyika. The journey was difficult and the caravan was attacked by Ruga-Ruga warriors several times. He reached Karema on 27 September 1882, where he found the station still held by Lieutenant Jérôme Becker, whose term of service had expired.[1]

Karema

.jpg.webp)

Yassagula, chief of the village of Karema, attacked the station soon after Storms arrived. Becker counterattacked with his askaris, put Yassagula's men to flight and destroyed the village few months later Yassagula submitted, and from then on was a reliable ally. Becker left the station on 17 November on his homeward journey. Storms strengthened and expanded the post, which was now called Fort Léopold, and started to grow vegetables. He responded to an attack on his couriers with an expedition that defeated the rebel chief on 23 April 1883. However, the German scientist Richard Böhm who accompanied Storms was struck by two bullets in the leg during this action and was laid up for several months.[1]

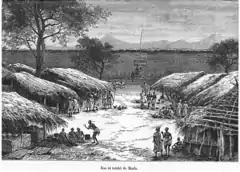

Mpala

Storms had been charged with establishing a second post on Lake Tanganyika. He left Böhm in charge of Karema. Storms embarked on 27 April 1883 with Böhm's companion Paul Reichard and 24 askaris and sailed to Mompara on the west shore of the lake. There he found a peaceful and friendly population who offered food. Looking for a good place to establish a post, he made contact with the chief Mpala, who gave permission to build the post in his territory. On 4 May 1883 the foundations of the station of Mpala were laid. Chief Mpala became a blood-brother in a ceremony on 25 June 1883. Storms left Reichart to supervise the work while he went to Ujiji to buy a boat and obtain some trade goods. Storms was back at Mpala on 15 August 1883. Both of his boats were wrecked in a storm shortly after his arrival, and he had to build another before he could return to Karema.[2]

The alliance with the chief Mpala proved valuable. The chief caught smallpox, but before dying ordered the village elders to respect Storms.[2] Storms gained authority during the two and a half years he spent at Mpala. The local chiefs came to rely on him for a monthly salary and for protection.[3] Storms had his people build a great square stockade 30 metres (98 ft) on each side, using five thousand trees. The walls were made of mudbrick and were 60 centimetres (24 in) thick. The interior had seventeen rooms around a covered courtyard.[4] However, on 19 May 1885 the stockade burned to the ground. Once the dried thatch had caught fire, little could be saved apart from the gunpowder.[5] On 6 September 1884 Storms was visited by White Fathers missionaries led by R. P. Moinet, whom he helped to settle in Tchanza, one day south of Mpala. On 30 November 1884 Reichart arrived at Mpala, returning from an exploration of Katanga, and told him that Böhm had died on the journey.[3]

Storms found himself in a violent confrontation with Lusinga Iwa Ngombe, a powerful slaver whom the explorer Joseph Thomson called a "sanguinary potentate".[6] In November, while in Karema, Storms heard that Lusinga was preparing to make war on Mpala. Storms hired 150 Rouga Rouga, crossed the lake and attacked Lusinga, who was defeated.[3] Lusinga was beheaded.[6] Another leader, Kansawara, who had previously submitted to Storms, decided to move into the vacancy left by Lusinga. He was defeated on 15 December 1884 and soon afterwards again submitted to Storms.[3]

Recall

At the Berlin Conference (1884-1885) the east side of the lake was assigned to the German sphere of influence.[7] King Leopold II of Belgium decided to focus his colonizing efforts on the lower Congo. He asked Mgr. Charles Lavigerie, the founder of the White Fathers missionary society, if he would like to replace the Belgian agents by missionaries at the two stations on Lake Tanganyika.[8]At the end of May 1885, Storms received a letter from Brussels recalling him.[3] When Storms heard that he was to be replaced, he was furious. However, when two French priests, Isaac Moinet and Auguste Moncet, reached Mpala on 5 July 1885, Captain Storms handed over the fort, arms and ammunition, a sailboat and a garrison of askaris who had been paid for six months.[8]

Moinet jokingly asked Storms what title he should take as successor to "His Majesty Emile the First, King of Tanganyika", and signed a letter he wrote to Storms "I, Moinet, Acting King of Mpala." However, the priests were committed to Lavigerie's dream of a Christian Kingdom in the heart of equatorial Africa, and saw the territory that Storms had acquired as the invaluable nucleus of the new state. After installing the missionaries at Mpala and Karema, Storms left for the coast at the end of July. After a difficult journey, he reached Europe on 21 December 1885.[3]

Later career

In February 1888 Storms was given the technical direction of the Belgian anti-slavery expedition to Lake Tanganyika. The Belgian Anti-Slavery Society, founded by Cardinal Lavigerie, had General Jacmart as President. The objective was to abolish the slave trade in Africa, and a corps of volunteers was sent to operate on Lake Tanganyika. On 20 December 1891 the society launched a boat named Storms on the lake.[3]

Storms reached the rank of General in the army. He died on 12 January 1918 at Ixelles, in Brussels.

Awards and commemoration

Storms was an officer of the Order of Leopold and received various decorations and honors. A monument was erected to him in his home town of Wetteren, and a bust was placed in the square of l'Industrie in Brussels,[3] today renamed Square de Meeûs. In the aftermath of the George Floyd protests, in June 2020, the bust was vandalized with red paint[9][10] On 1 July 2020 it was reported that the communal authorities of Ixelles planned to remove the bust from the square and transfer it to the Royal Museum for Central Africa.[11] On 30 June 2022 the bust was removed by the communal authorities.[12]

Writings

- Slavery between Lake Tanganyika and the coast: the anti-slavery expedition (Anti-slavery society, May 1890, p. 161).

- The problem of the movement of water of Tanganyika (Bulletin of the Belgian Geog. Society, 1886, p. 50-61).

- Notes on the ethnography of eastern equatorial Africa (Bulletin of the Belgian Geog. Society, Vol. V, 1886-1887, p. 91, in collaboration with Dr. Y. Jacques).

- "L'échange du sang", Le Mouvement Géographique, 2 (1885), p. 3.

- "Une séance de féticheur", Le Mouvement Géographique, 2 (1885), p. 7.

- "Le Tanganika: quelques particularités sur les moeurs africaines", Bulletin de la Société Royale Belge de Géographie, 10 (1886), pp. 195-196.

- "Objets sculptés du Manyéma et du Sankuru", Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie de Bruxelles, 7 (1888–1889), p. 166.

- The work of antislavery, Mouv. antiescl., (1890), pp. 63-72.

- "Le Potager de Karema", Le Mouvement Géographique, 11 (1894), p. 74.

- Map of Tanganyika (Exhibitions of Brussels and Antwerp).

Further reading

- Norman R. Bennett, "Captain Storms in Tanganyika, 1882–1885", Tanganyika Notes and Records, 54 (1960), pp. 51-63.

References

Citations

- Coosemans 1948, p. 899.

- Coosemans 1948, p. 900.

- Coosemans 1948, p. 901.

- Roberts 2012, p. 29.

- Roberts 2012, p. 43.

- Roberts 2012, p. 1.

- Boulger 1898, p. 25.

- Casier 1987.

- "Statue of Belgian Soldier Émile Storms". gettyimages.be. Getty Images. 14 June 2020.

- Esther, Kouablan Francine (2018-04-26). "En Belgique, on glorifie un meurtrier-collectionneur de restes humains". MRAX (in French). Retrieved 2021-02-02.

- Gabriela Galindo (1 July 2020). "Ixelles will remove bust of Leopold II's 'ruthless' colonial general". The Brussels Times.

- "Décolonisation de l'espace public: la statue du général Storms démontée à Ixelles". La Libre Belgique. 30 June 2022.

Sources

- Boulger, Demetrius Charles (1898). The Congo State: Or, the Growth of Civilisation in Central Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-108-05069-2. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Casier, P. Jacques (1987). "Le royaume chrétien de Mpala : 1887 - 1893". Souvenirs Historiques. Nuntiuncula, Bruxelles (13). Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Coosemans, M. (1948). "Storms (Emile Pierre Joseph)". Biographie Coloniale Belge. Vol. 1. Institut Royal Colonial Belge. Retrieved 2013-04-10.

- Roberts, Allen F. (2012-12-20). A Dance of Assassins: Performing Early Colonial Hegemony in the Congo. Indiana University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-253-00743-8. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Roberts, Allen F. (1991). "History, Ethnicity and Change in the 'Christian Kingdom' of Southeastern Zaire". In Leroy Vail (ed.). The Creation of Tribalism in Southern Africa. University of California Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-520-07420-0. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Archive Emile Storms, Royal Museum for Central Africa