Epaulette

Epaulette (/ˈɛpəlɛt/; also spelled epaulet)[1] is a type of ornamental shoulder piece or decoration used as insignia of rank by armed forces and other organizations. Flexible metal epaulettes (usually made from brass) are referred to as shoulder scales.

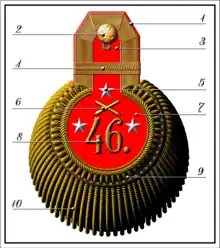

1. Lining

2. Button

3. Spine

4. Attente/shoulder strap

5. Stars (or pips)

6. Branch insignia

7. Field

8. Unit number

9. Neck (bezel)

10. Fringe

In the French and other armies, epaulettes are also worn by all ranks of elite or ceremonial units when on parade. It may bear rank or other insignia, and should not be confused with a shoulder mark – also called a shoulder board, rank slide, or slip-on – a flat cloth sleeve worn on the shoulder strap of a uniform (although the two terms are often used interchangeably).[2]

Etymology

Épaulette (French: [e.po.lɛt]) is a French word meaning "little shoulder" (diminutive of épaule, meaning "shoulder").

How to wear

Epaulettes are fastened to the shoulder by a shoulder strap or passenten,[3] a small strap parallel to the shoulder seam, and the button near the collar, or by laces on the underside of the epaulette passing through holes in the shoulder of the coat. Colloquially, any shoulder straps with marks are also called epaulettes. The placement of the epaulette, its color and the length and diameter of its bullion fringe are used to signify the wearer's rank. At the join of the fringe and the shoulderpiece is often a metal piece in the form of a crescent. Although originally worn in the field, epaulettes are now normally limited to dress or ceremonial military uniforms.

History

Epaulettes bear some resemblance to the shoulder pteruges of ancient Greco-Roman military costumes. However, their direct origin lies in the bunches of ribbons worn on the shoulders of military coats at the end of the 17th century, which were partially decorative and partially intended to prevent shoulder belts from slipping. These ribbons were tied into a knot that left the fringed end free. This established the basic design of the epaulette as it evolved through the 18th and 19th centuries.[5]

From the 18th century on, epaulettes were used in the French and other armies to indicate rank. The rank of an officer could be determined by whether an epaulette was worn on the left shoulder, the right shoulder, or on both. Later a "counter-epaulette" (with no fringe) was worn on the opposite shoulder of those who wore only a single epaulette. Epaulettes were made in silver or gold for officers and in cloth of various colors for the enlisted men of various arms.

Apart from that, flexible metal epaulettes were quite popular among certain armies in the 19th century, but were rarely worn on the field. Referred to as shoulder scales, they were e.g. an accoutrement of the US Cavalry, US Infantry and the US Artillery, from 1854 to 1872.

By the early 18th century, epaulettes had become the distinguishing feature of commissioned rank. This led officers of military units still without epaulettes to petition for the right to wear epaulettes to ensure that their status would be recognized.[6] During the Napoleonic Wars and subsequently through the 19th century, grenadiers, light infantry, voltigeurs and other specialist categories of infantry in many European armies wore cloth epaulettes with wool fringes in various colors to distinguish them from ordinary line infantry. Flying artillery wore epaulette-esque shoulder pads. Heavy artillery wore small balls representing ammunition on their shoulders.

An intermediate form in some services, such as the Russian Army, is the shoulder board, which neither has a fringe nor extends beyond the shoulder seam. This originated during the 19th century as a simplified version for service wear of the heavy and conspicuous full dress epaulette with bullion fringes.

Modern derivations

Today, epaulettes have mostly been replaced by a five-sided flap of cloth called a shoulder board, which is sewn into the shoulder seam and the end buttoned like an epaulette.

From the shoulder board was developed the shoulder mark, a flat cloth tube that is worn over the shoulder strap and carries embroidered or pinned-on rank insignia. The advantages of this are the ability to easily change the insignia as occasions warrant.

Airline pilot uniform shirts generally include cloth flattened tubular epaulettes having cloth or bullion braid stripes, attached by shoulder straps integral to the shirts. The rank of the wearer is designated by the number of stripes: traditionally four for a captain, three for senior first officer or first officer, and two for either a first officer or second officer. However, rank insignia are airline specific. For example, at some airlines, two stripes denote junior first officer and one stripe second officer (cruise or relief pilot). Airline captains' uniform caps usually will have a braid pattern on the bill. These uniform specifications change depending on the company's policy.

Belgium

In the Belgian army, red epaulettes with white fringes are worn with the ceremonial uniforms of the Royal Escort while fully red ones are worn by the Grenadiers. Trumpeters of the Royal Escort are distinguished by all red epaulettes while officers of the two units wear silver or gold respectively.

Canada

In the Canadian Armed Forces, epaulettes are still worn on some Army Full Dress, Patrol Dress, and Mess Dress uniforms. Epaulettes in the form of shoulder boards are worn with the officer's white Naval Service Dress.

After the unification of the Forces, and prior to the issue of the distinctive environmental uniforms, musicians of the Music Branch wore epaulettes of braided gold cord.

France

Until 1914, officers of most French Army infantry regiments wore gold epaulettes in full dress, while those of mounted units wore silver. No insignia was worn on the epaulette itself, though the bullion fringe falling from the crescent differed according to rank.[7] Other ranks of most branches of the infantry, as well as cuirassiers wore detachable epaulettes of various colours (red for line infantry, green for Chasseurs, yellow for Colonial Infantry etc.) with woollen fringes, of a traditional pattern that dated back to the 18th century. Other cavalry such as hussars, dragoons and chasseurs à cheval wore special epaulettes of a style originally intended to deflect sword blows from the shoulder.

In the modern French Army, epaulettes are still worn by those units retaining 19th-century-style full dress uniforms, notably the ESM Saint-Cyr and the Garde Républicaine. The French Foreign Legion continued to wear their green and red epaulettes, except for a break from 1915 to 1930. In recent years, the Marine Infantry and some other units have readopted their traditional fringed epaulettes in various colours for ceremonial parades. The Marine nationale and the Armée de l'Air do not use epaulettes, but non-commissioned and commissioned officers wear a gilded shoulder strap called attentes, the original function of which was to clip the epaulette onto the shoulder. The attentes are also worn by Army generals on their dress uniforms.[8]

Cadets of the ESM Saint-Cyr in full uniform. The gold epaulettes shown are those of cadet officers, while those of ordinary cadets are red.

Cadets of the ESM Saint-Cyr in full uniform. The gold epaulettes shown are those of cadet officers, while those of ordinary cadets are red. Yellow epaulettes of the French Marines

Yellow epaulettes of the French Marines Red and green epaulette of the French Foreign Legion

Red and green epaulette of the French Foreign Legion Gendarmerie nationale cadet in full uniform. Notice the attente keeping the epaulette onto the shoulder.

Gendarmerie nationale cadet in full uniform. Notice the attente keeping the epaulette onto the shoulder.

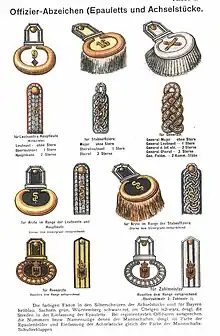

Germany

Until World War I, officers of the Imperial German Army generally wore silver epaulettes as a distinguishing feature of their full-dress uniforms. For ranks up to and including captain these were "scale" epaulettes without fringes, for majors and colonels with fine fringes and for generals with a heavy fringe. The base of the epaulette was of regimental colors. For ordinary duty, dress "shoulder-cords" of silver braid intertwined with state colors, were worn.[9]

During the period 1919–1945, German Army uniforms were known for a four cord braided "figure-of-eight" decoration which acted as a shoulder board for senior and general officers. This was called a "shoulder knot" and was in silver with the specialty color piping (for field officers) and silver with red border (for generals). Although it was once seen on US Army uniforms, it remains only in the mess uniform. A similar form of shoulder knot was worn by officers of the British Army in full dress until 1914 and is retained by the Household Cavalry today. Epaulettes of this pattern are used by the Republic of Korea Army's general officers and were widely worn by officers of the armies of Venezuela, Chile, Colombia, Paraguay, Ecuador and Bolivia; all of which formerly wore uniforms closely following the Imperial German model. The Chilean Army still retains the German style of epaulette in the uniforms of its ceremonial units, the Military Academy and the NCO School while the 5th Cavalry Regiment "Aca Caraya" of the Paraguayan Army sports both epaulettes and shoulder knots in its dress uniforms (save for a platoon wearing Chaco War uniforms). Epaulettes of the German pattern (as well as shoulder knots) are used by officers of ceremonial units and schools of the Bolivian Army.

Haiti

Gold epaulettes in Haiti, were frequently worn throughout the 18th and 19th centuries in full dress.[10] During the Haitian Revolution, Gen. Charles Leclerc of the French Army wrote a letter to Napoleon Bonaparte saying, "We must destroy half of those in the plains and must not leave a single colored person in the colony who has worn an epaulette.”[11][12]

Haitian revolutionary leader Toussaint Louverture, wears a four-starred general-in-chief's uniform with epaulettes.

Haitian revolutionary leader Toussaint Louverture, wears a four-starred general-in-chief's uniform with epaulettes._Portrait.jpg.webp) Jean-Pierre Boyer, former battalion commander of the French Revolutionary Army, later became President of Haiti controlling the entire island of Hispaniola for twenty-two years.

Jean-Pierre Boyer, former battalion commander of the French Revolutionary Army, later became President of Haiti controlling the entire island of Hispaniola for twenty-two years.

Ottoman Empire

During the Tanzimat period in the Ottoman Empire, western style uniforms and court dresses were adopted. Gold epaulettes were worn in full dress.

.tiff.jpg.webp) Ottoman government officials in full dress

Ottoman government officials in full dress.tiff.jpg.webp) Another depiction of Ottoman government officials in full dress

Another depiction of Ottoman government officials in full dress

Russian Empire

Both the Imperial Russian Army and the Imperial Russian Navy sported different forms of epaulettes for its officers and senior NCOs. Today the current Kremlin Regiment continues the epaulette tradition.

.png.webp)

- Types of epaulette of the Russian Empire

1. Infantry

1a. Subaltern-officer, here: poruchik of the 13th Life Grenadier Erivan His Imperial Majesty's regiment

1b. Staff-officer, here: polkovnik of the 46th Artillery brigade

1c. General, here: Field marshal of Russian Vyborg 85th infantry regiment of German Emperor Wilhelm II.

2. Guards

2a. Subaltern-officer, here: captain of the Mikhailovsky artillery school

2b. Staff-officer, here: polkovnik of Life Guards Lithuanian regiment.

2c. Flagofficer, here: Vice-Admiral

3. Cavalry

3a. Of the lower ranks, here: junior unteroffizier (junior non-commissioned officer) of the 3rd Smolensk lancers HIM Emperor Alexander III regiment

3b. Subaltern-officer, here: podyesaul of Russian Kizlyar-Grebensky 1st Cossack horse regiment.

3c. Staff-officer, here: lieutenant-colonel of the 2nd Life Dragoon Pskov Her Imperial Majesty Empress Maria Feodorovna regiment

3d. General, here: General of the cavalry.

4. Others

4a. Subaltern-officer, here: Titular councillor, veterinary physician.

4b. Staff-officer, here: flagship mechanical engineer, Fleet Engineer Mechanical Corps.

4c. General, here: Privy councillor, Professor of the Imperial Military medical Academy.

Sweden

Epaulettes first appeared on Swedish uniforms in the second half of the 18th century. The epaulette was officially incorporated into Swedish uniform regulations in 1792, although foreign recruited regiments had had them earlier. Senior officers were to wear golden crowns to distinguish their rank from lower ranking officers who wore golden stars.

Epaulettes were discontinued on the field uniform in the mid-19th century, switching to rank insignia on the collar of the uniform jacket. Epaulettes were discontinued when they were removed from the general issue dress uniform in the 1930s. They are, however, still worn by the Royal Lifeguards and by military bands when in ceremonial full dress.

Royal Lifeguards Officer in ceremonial full dress at the Royal Palace in Stockholm

Royal Lifeguards Officer in ceremonial full dress at the Royal Palace in Stockholm Swedish king Oscar II wearing an admiral's uniform, as shown by the three stars on his epaulettes

Swedish king Oscar II wearing an admiral's uniform, as shown by the three stars on his epaulettes

United Kingdom

Epaulettes first appeared on British uniforms in the second half of the 18th century. The epaulette was officially incorporated into Royal Navy uniform regulations in 1795, although some officers wore them before this date. Under this system, flag officers wore silver stars on their epaulettes to distinguish their ranks. A captain with at least three years seniority had two plain epaulettes, while a junior captain wore one on the right shoulder, and a commander one on the left.[13]

In 1855, army officers' large, gold-fringed epaulettes were abolished[14] and replaced by a simplified equivalent officially known as twisted shoulder-cords.[15] These were generally worn with full dress uniforms. Naval officers retained the historic fringed epaulettes for full dress during this period. These were officially worn until 1960 when they were replaced with shoulder boards. Today, only the officers of the Yeomen of the Guard, the Military Knights of Windsor, the Elder Brethren of Trinity House and the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports retain fringed epaulettes.

British cavalry on active service in the Sudan (1898) and during the Boer War (1899–1902) sometimes wore epaulettes made of chainmail to protect against sword blows landing on the shoulder. The blue "Number 1 dress" uniforms of some British cavalry regiments and yeomanry units still retain this feature in ornamental silvered form.[16]

With the introduction of khaki service dress in 1902, the British Army stopped wearing epaulettes in the field, switching to rank insignia embroidered on the cuffs of the uniform jacket. During World War I, this was found to make officers a target for snipers, so the insignia was frequently moved to the shoulder straps, where it was less conspicuous.

The current multi-terrain pattern (MTP) and the older combat uniform (DPM) have the insignia formerly used on shoulder straps displayed on a single strap worn vertically in the centre of the chest. Earlier DPM uniforms had shoulder straps on the shoulders, though only officers wore rank on rank slides which attached to these straps, other ranks wore rank on the upper right sleeve at this time though later on regimental titles were worn on the rank slides. This practice continued into later patterns where rank was worn on the chest, rank was also added.

In modern times, epaulettes are frequently worn by professionals within the ambulance service to signify clinical grade for easy identification. These are typically green in colour with gold writing and may contain one to three pips to signify higher managerial ranks.

United States

Epaulettes were authorized for the United States Navy in the first official uniform regulations, Uniform of the Navy of the United States, 1797. Captains wore an epaulette on each shoulder, lieutenants wore only one, on the right shoulder.[17][18] By 1802, lieutenants wore their epaulette on the left shoulder, with lieutenants in command of a vessel wearing them on the right shoulder;[19] after the creation of the rank of master commandants, they wore their epaulettes on the right shoulder similar to lieutenants in command.[20] By 1842, captains wore epaulettes on each shoulder with a star on the straps, master commandant were renamed commander in 1838 and wore the same epaulettes as captains except the straps were plain, and lieutenants wore a single epaulette similar to those of the commander, on the left shoulder.[21] After 1852, captains, commanders, lieutenants, pursers, surgeons, passed assistant and assistant surgeons, masters in the line of promotion and chief engineers wore epaulettes.[22]

Epaulettes were specified for all United States Army officers in 1832; infantry officers wore silver epaulettes, while those of the artillery and other branches wore gold epaulettes, following the French manner. The rank insignia was of a contrasting metal, silver on gold and vice versa.

In 1851, the epaulettes became universally gold. Both majors and second lieutenants had no specific insignia. A major would have been recognizable as he would have worn a senior field officer's more elaborate epaulette fringes. The rank insignia was silver for senior officers and gold for the bars of captains and first lieutenants. The choice of silver eagles over gold ones is thought to be one of economy; there were more cavalry and artillery colonels than infantry, so replacing the numerically fewer gold ones was cheaper.

Shoulder straps were adopted to replace epaulettes for field duty in 1836.

Licensed officers of the U.S. Merchant Marine may wear shoulder marks and sleeve stripes appropriate to their rank and branch of service. Deck officers wear a foul anchor above the stripes on their shoulder marks, and engineering officers wear a three-bladed propeller. In the U.S. Merchant Marine, the correct wear of shoulder marks depicting the fouled anchor is with the un-fouled stock of the anchor forward on the wearer.

In popular culture

In literature, film and political satire, dictators, particularly of unstable Third World nations, are often depicted in military dress with oversized gold epaulettes.

The eponymous character of Revolutionary Girl Utena along with the rest of the duelists have stylised epaulettes on their uniforms.

The members of the Teikoku Kageki-dan from Sakura Wars have epaulettes on their uniforms.

Grand Admiral Thrawn, a member on the Galactic Empire's Imperial Fleet on the Star Wars franchise including Star Wars Rebels wore gold epaulettes on his uniform.

Clara Stahlbaum and Captain Philip Hoffman on the 2018 film The Nutcracker and the Four Realms wore epaulettes on their uniforms.

The Genie wore gold epaulettes on some suits in the 1992 film Aladdin and the 1996 sequel Aladdin and the King of Thieves.

Stephen Fry wore gold epaulettes when playing the Duke of Wellington on Blackadder the Third.

Gallery

Carl von Clausewitz, Prussian general

Carl von Clausewitz, Prussian general Royal Guardsman in Oslo, Norway

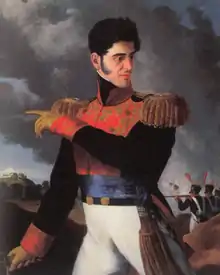

Royal Guardsman in Oslo, Norway Simón Bolívar, Venezuelan military leader

Simón Bolívar, Venezuelan military leader

Ivan Skobelev, Russian general, 1826

Ivan Skobelev, Russian general, 1826_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Pedro I, Emperor of Brazil (also King of Portugal as Pedro IV)

Pedro I, Emperor of Brazil (also King of Portugal as Pedro IV)

See also

- Shoulder loops in the uniform of the Boy Scouts of America

- Spaulder

- Aiguillette

- Attentes

- Swallow's nest (uniform)

References

- "Definition of EPAULET". Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- “Uniform Dress Guidelines”. Canadian Coast Guard. ver 26 06/27/08, p. 7

- Carman, W. Y. (1977). A Dictionary of Military Uniform. p. 100. ISBN 0-684-15130-8.

- "Military jacket". The Met.

- John Mollo, page 49 "Military Fashion", ISBN 0-214-65349-8

- Wilkinson-Latham, R: The Royal Navy 1790–1970, page 5. Osprey Publishing, 1977

- André Jouineau, Officers and Soldiers of the French Army 1914, ISBN 978-2-352-50104-6

- Gaujac, Paul (2012). Officers et Soldats de L'Armee Francaise. p. 9. ISBN 978-2-35250-195-4.

- page 590, Volume XXVII, Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition

- "Education, Volume 23". New England Publishing Company. 1903. p. 281. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- "General Leclerc in Saint-Domingue 1801–1802". Brown University. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- Dayan, Joan (10 March 1998). Haiti, History, and the Gods. p. XVI. ISBN 9780520213685. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- "Epaulettes at the National Maritime Museum website". NMM.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- Major R.M. Barnes, page 260 "A History of the Regiments and Uniforms of the British Army", First Sphere Books edition 1972

- Section 24 "Dress Regulations for the Army 1900

- R.M. Barnes page 316 "Military Uniforms of Britain and the Empire", Sphere Books 1972

- Rankin, Col. Robert H.: "Uniforms of the Sea Services", 1962

- "Uniform Regulations, 1797". Archived from the original on 25 June 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- "Uniform Regulations, 1802". Archived from the original on 14 September 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- "Uniform Regulations, 1814". Archived from the original on 7 April 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- "Uniform Regulations, 1842". Archived from the original on 7 April 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- "Uniform Regulations, 1852". Archived from the original on 7 April 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2009.