Third World

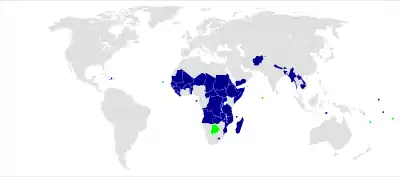

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War and it was used to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Western European nations and their allies represented the "First World", while the Soviet Union, China, Cuba, North Korea, Vietnam and their allies represented the "Second World". This terminology provided a way of broadly categorizing the nations of the Earth into three groups based on political divisions. Due to the complex history of evolving meanings and contexts, there is no clear or agreed-upon definition of the Third World.[1] Strictly speaking, "Third World" was a political, rather than an economic, grouping.[2]

Because many Third World countries were economically poor and non-industrialized, it became a stereotype to refer to developing countries as "third world countries". Some countries in the Eastern Bloc, such as Cuba, were often regarded as "Third World". The Third World was normally seen to include many countries with colonial pasts in Africa, Latin America, Oceania, and Asia. It was also sometimes taken as synonymous with countries in the Non-Aligned Movement. In the dependency theory of thinkers like Raúl Prebisch, Walter Rodney, Theotônio dos Santos, and Andre Gunder Frank, the Third World has also been connected to the world-systemic economic division as "periphery" countries dominated by the countries comprising the economic "core".[1]

Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, the term Third World has decreased in use. It is being replaced with terms such as developing countries, least developed countries or the Global South. The concept itself has become outdated as it no longer represents the current political or economic state of the world and as historically poor countries have transited different income stages. In the Cold War, some European democracies (Austria, Finland, Republic of Ireland, Sweden, and Switzerland) were neutral in the sense of not joining NATO, but were prosperous, never joined the Non-Aligned Movement, and seldom self-identified as part of the Third World.

Etymology

French demographer, anthropologist, and historian Alfred Sauvy, in an article published in the French magazine L'Observateur, August 14, 1952, coined the term third world (tiers monde), referring to countries that were playing a small role in international trade and business.[3] His usage was a reference to the Third Estate (tiers état), the commoners of France who, before and during the French Revolution, opposed the clergy and nobles, who composed the First Estate and Second Estate, respectively (hence the use of the older form tiers rather than the modern troisième for "third"). Sauvy wrote, "This third world ignored, exploited, despised like the third estate also wants to be something."[4] In the context of the Cold War, he conveyed the concept of political non-alignment with either the capitalist or communist bloc.[5] Simplistic interpretations quickly led to the term merely designating these unaligned countries.[6]

Related concepts

Third World vs. Three Worlds

The "Three Worlds Theory" developed by Mao Zedong is different from the Western theory of the Three Worlds or Third World. For example, in the Western theory, China and India belong respectively to the second and third worlds, but in Mao's theory both China and India are part of the Third World which he defined as consisting of exploited nations.

Third Worldism

Third Worldism is a political movement that argues for the unity of third-world nations against first-world influence and the principle of non-interference in other countries' domestic affairs. Groups most notable for expressing and exercising this idea are the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and the Group of 77 which provide a base for relations and diplomacy between not just the third-world countries, but between the third-world and the first and second worlds. The notion has been criticized as providing a fig leaf for human rights violations and political repression by dictatorships.[7]

Since 1990, this term has been redefined to make it more correct politically. Initially, the term “third world” meant that a nation is “under-developed”.[8] However, today it is replaced by the term “developing".

Great Divergence and Great Convergence

Many times there is a clear distinction between First and Third Worlds. When talking about the Global North and the Global South, the majority of the time the two go hand in hand. People refer to the two as "Third World/South" and "First World/North" because the Global North is more affluent and developed, whereas the Global South is less developed and often poorer.[9]

To counter this mode of thought, some scholars began proposing the idea of a change in world dynamics that began in the late 1980s, and termed it the Great Convergence.[10] As Jack A. Goldstone and his colleagues put it, "in the twentieth century, the Great Divergence peaked before the First World War and continued until the early 1970s, then, after two decades of indeterminate fluctuations, in the late 1980s, it was replaced by the Great Convergence as the majority of Third World countries reached economic growth rates significantly higher than those in most First World countries".[11]

Others have observed a return to Cold War-era alignments (MacKinnon, 2007; Lucas, 2008), this time with substantial changes between 1990–2015 in geography, the world economy and relationship dynamics between current and emerging world powers; not necessarily redefining the classic meaning of First, Second, and Third World terms, but rather which countries belong to them by way of association to which world power or coalition of countries — such as G7, the European Union, OECD; G20, OPEC, N-11, BRICS, ASEAN; the African Union, and the Eurasian Union.

History

Most Third World countries are former colonies. Having gained independence, many of these countries, especially smaller ones, were faced with the challenges of nation- and institution-building on their own for the first time. Due to this common background, many of these nations were "developing" in economic terms for most of the 20th century, and many still are. This term, used today, generally denotes countries that have not developed to the same levels as OECD countries, and are thus in the process of developing.

In the 1980s, economist Peter Bauer offered a competing definition for the term "Third World". He claimed that the attachment of Third World status to a particular country was not based on any stable economic or political criteria, and was a mostly arbitrary process. The large diversity of countries considered part of the Third World — from Indonesia to Afghanistan — ranged widely from economically primitive to economically advanced and from politically non-aligned to Soviet- or Western-leaning. An argument could also be made for how parts of the U.S. are more like the Third World.[12]

The only characteristic that Bauer found common in all Third World countries was that their governments "demand and receive Western aid," the giving of which he strongly opposed. Thus, the aggregate term "Third World" was challenged as misleading even during the Cold War period, because it had no consistent or collective identity among the countries it supposedly encompassed.

Development aid

During the Cold War, unaligned countries of the Third World[1] were seen as potential allies by both the First and Second World. Therefore, the United States and the Soviet Union went to great lengths to establish connections in these countries by offering economic and military support to gain strategically located alliances (e.g., the United States in Vietnam or the Soviet Union in Cuba).[1] By the end of the Cold War, many Third World countries had adopted capitalist or communist economic models and continued to receive support from the side they had chosen. Throughout the Cold War and beyond, the countries of the Third World have been the priority recipients of Western foreign aid and the focus of economic development through mainstream theories such as modernization theory and dependency theory.[1]

By the end of the 1960s, the idea of the Third World came to represent countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America that were considered underdeveloped by the West based on a variety of characteristics (low economic development, low life expectancy, high rates of poverty and disease, etc.).[6] These countries became the targets for aid and support from governments, NGOs and individuals from wealthier nations. One popular model, known as Rostow's stages of growth, argued that development took place in 5 stages (Traditional Society; Pre-conditions for Take-off; Take-off; Drive to Maturity; Age of High Mass Consumption).[13] W. W. Rostow argued that Take-off was the critical stage that the Third World was missing or struggling with. Thus, foreign aid was needed to help kick-start industrialization and economic growth in these countries.[13]

Perceived "End of the Third World"

Since 1990 the term "Third World" has been redefined in many evolving dictionaries in several languages to refer to countries considered to be underdeveloped economically and/or socially. From a "political correctness" standpoint the term "Third World" may be considered outdated, which its concept is mostly a historical term and cannot fully address what means by developing and less-developed countries today. Around the early 1960s, the term "underdeveloped countries" occurred and the Third World serves to be its synonym, but after it has been officially used by politicians, 'underdeveloped countries' is soon been replaced by 'developing' and 'less-developed countries,' because the prior one shows hostility and disrespect, in which the Third World is often characterized with stereotypes.[14] The whole 'Four Worlds' system of classification has also been described as derogatory because the standard mainly focused on each nations' Gross National Product.[15]

The general definition of the Third World can be traced back to the history that nations positioned as neutral and independent during the Cold War were considered as Third World Countries, and normally these countries are defined by high poverty rates, lack of resources, and unstable financial standing.[16] However, based on the rapid development of modernization and globalization, countries that were used to be considered as Third World countries achieve big economic growth, such as Brazil, India, and Indonesia, which can no longer be defined by poor economic status or low GNP today. The differences among nations of the Third World are continually growing throughout time, and it will be hard to use the Third World to define and organize groups of nations based on their common political arrangements since most countries live under diverse creeds in this era, such as Mexico, El Salvador, and Singapore, which they all have their own political system.[17] The Third World categorization becomes anachronistic since its political classification and economic system are distinct to be applied in today's society. Based on the Third World standards, any region of the world can be categorized into any of the four types of relationships among state and society, and will eventually end in four outcomes: praetorianism, multi-authority, quasi-democratic and viable democracy.[18] However, political culture is never going to be limited by the rule and the concept of the Third World can be circumscribed.

References

- Tomlinson, B.R. (2003). "What was the Third World". Journal of Contemporary History. 38 (2): 307–321. doi:10.1177/0022009403038002135. S2CID 162982648.

- Silver, Marc (4 January 2015). "If You Shouldn't Call It The Third World, What Should You Call It?". NPR. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Sauvi, Alfred (August 14, 1952). "TROIS MONDES, UNE PLANÈTE". www.homme-moderne.org (in French). Retrieved 2023-03-27.

- Literal translation from French

- Wolf-Phillips, Leslie (1987). "Why 'Third World'?: Origin, Definition and Usage". Third World Quarterly. 9 (4): 1311–1327. doi:10.1080/01436598708420027.

- Gregory, Derek, ed. (2009). Dictionary of Human Geography. et al. (5th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Pithouse, Richard (2005). Report Back from the Third World Network Meeting Accra, 2005 (Report). Centre for Civil Society. pp. 1–6. Archived from the original on 2011-10-28.

- Nash, Andrew (2003-01-01). "Third Worldism". African Sociological Review. 7 (1). doi:10.4314/asr.v7i1.23132. ISSN 1027-4332.

- Mimiko, Oluwafemi (2012). "Globalization: The Politics of Global Economic Relations and International Business". Carolina Academic Press: 49.

- Korotayev, A.; Zinkina, J. (2014). "On the structure of the present-day convergence". Campus-Wide Information Systems. 31 (2/3): 139–152. doi:10.1108/CWIS-11-2013-0064. Archived from the original on 2014-10-08.

- Korotayev, Andrey; Goldstone, Jack A.; Zinkina, Julia (June 2015). "Phases of global demographic transition correlate with phases of the Great Divergence and Great Convergence". Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 95: 163. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2015.01.017. Archived from the original on 2015-07-03.

- "Third World America" Archived 2014-02-13 at the Wayback Machine, MacLeans, September 14, 2010

- Westernizing the Third World (Ch 2), Routledge

- Wolf-Phillips, Leslie (1979). "Why Third World?". Third World Quarterly. 1 (1): 105–115. doi:10.1080/01436597908419410. ISSN 0143-6597. JSTOR 3990587.

- Wolf-Phillips, Leslie (1987). "Why 'Third World'?: Origin, Definition and Usage". Third World Quarterly. 9 (4): 1311–1327. doi:10.1080/01436598708420027. ISSN 0143-6597. JSTOR 3991655.

- Drakakis-Smith, D. W. (2000). Third World Cities. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-19882-0. Archived from the original on 2021-07-15. Retrieved 2020-11-22 – via Google Books.

- Rieff, David (1989). "In The Third World". Salmagundi (81): 61–65. ISSN 0036-3529. JSTOR 40548016.

- Kamrava, Mehran (1995). "Political Culture and a New Definition of the Third World". Third World Quarterly. 16 (4): 691–701. doi:10.1080/01436599550035906. ISSN 0143-6597. JSTOR 3993172.

Further reading

- Aijaz, Ahmad (1992). In theory: Classes, nations, literatures. London: Verso Books.

- Bauer, Peter T. (1981). Equality, the Third World, and economic delusion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674259850.

- Chaouad, Robert. (2016) Emergence: genesis and circulation of a notion that has become a category of analysis, International and Strategic Review, vol. 103, no. 3, pp. 55-66.

- Escobar, Arturo (2011). Encountering development: The making and unmaking of the Third World (revised ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Furtado, Celso (1964). Development and underdevelopment. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Lawrence, Mark Atwood. The End of Ambition: The United States and the Third World in the Vietnam War Era (Princeton University Press, 2021) ISBN 978-0-691-12640-1 | Website: rjissf.org online reviews

- Melkote, Srinivas R. & Steeves, H. Leslie. (1991). Communication for development in the Third World: Theory and practice for Empowerment . New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

- Sheppard, Eric & Porter, Wayland P. (1998). A world of difference: Society, nature, development. New York: Guilford Press.

- Rangel, Carlos (1986). Third World Ideology and Western Reality. New Brunswick: Transaction Books. ISBN 9780887386015.

- Smith, Brian C. (2013). Understanding Third World Politics: Theories of Political Change and Development (4th ed.). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Aijaz, Charles K. (1973). The political economy of development and underdevelopment. New York: Random House.