Full stop

The full stop (Commonwealth English), period (North American English), or full point . is a punctuation mark used for several purposes, most often to mark the end of a declarative sentence (as distinguished from a question or exclamation).[lower-alpha 1]

| . | |

|---|---|

Full stop or Period | |

| U+002E . FULL STOP HTML . |

A full stop is frequently used at the end of word abbreviations – in British usage, primarily truncations like Rev., but not after contractions like Revd; in American English, it is used in both cases. It may be placed after an initial letter used to abbreviate a word. It is often placed after each individual letter in acronyms and initialisms (e.g. "U.S.A."). However, the use of full stops after letters in an initialism or acronym is declining, and many of these without punctuation have become accepted norms (e.g., "UK" and "NATO").[lower-alpha 2]

The mark is also used to indicate omitted characters or, in a series as an ellipsis (...), to indicate omitted words.

In the English-speaking world, a punctuation mark identical to the full stop is used as the decimal separator and for other purposes, and may be called a point. In computing, it is called a dot.[2] It is sometimes called a baseline dot to distinguish it from the interpunct (or middle dot).[2][3]

History

Ancient Greek origin

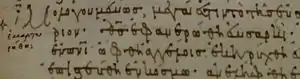

The full stop symbol derives from the Greek punctuation introduced by Aristophanes of Byzantium in the 3rd century BCE. In his system, there were a series of dots whose placement determined their meaning.

stigmḕ teleía, stigmḕ mésē and hypostigmḕ

The full stop at the end of a completed thought or expression was marked by a high dot ⟨˙⟩, called the stigmḕ teleía (στιγμὴ τελεία) or "terminal dot". The "middle dot" ⟨·⟩, the stigmḕ mésē (στιγμὴ μέση), marked a division in a thought occasioning a longer breath (essentially a semicolon), while the low dot ⟨.⟩, called the hypostigmḕ (ὑποστιγμή) or "underdot", marked a division in a thought occasioning a shorter breath (essentially a comma).[4]

Medieval simplification

In practice, scribes mostly employed the terminal dot; the others fell out of use and were later replaced by other symbols. From the 9th century onwards, the full stop began appearing as a low mark (instead of a high one), and by the time printing began in Western Europe, the lower dot was regular and then universal.[4]

Medieval Latin and modern English period

The name period is first attested (as the Latin loanword peridos) in Ælfric of Eynsham's Old English treatment on grammar. There, it is distinguished from the full stop (the distinctio), and continues the Greek underdot's earlier function as a comma between phrases.[5] It shifted its meaning, to a dot marking a full stop, in the works of the 16th-century grammarians.[5] In 19th-century texts, both British English and American English were consistent in their usage of the terms period and full stop.[6][1] The word period was used as a name for what printers often called the "full point", the punctuation mark that was a dot on the baseline and used in several situations. The phrase full stop was only used to refer to the punctuation mark when it was used to terminate a sentence.[1] This terminological distinction seems to be eroding. For example, the 1998 edition of Fowler's Modern English Usage used full point for the mark used after an abbreviation, but full stop or full point when it was employed at the end of a sentence;[7] the 2015 edition, however, treats them as synonymous (and prefers full stop),[8] and New Hart's Rules does likewise (but prefers full point).[9] In 1989, the last edition (1989) of the original Hart's Rules (before it became The Oxford Guide to Style in 2002) exclusively used full point.[10]

Usage

Full stops are the most commonly used punctuation marks; analysis of texts indicate that approximately half of all punctuation marks used are full stops.[11][12]

Ending sentences

Full stops indicate the end of sentences that are not questions or exclamations.

After initials

It is usual in North American English to use full stops after initials; e.g. A. A. Milne,[13] George W. Bush.[14] British usage is less strict.[15] A few style guides discourage full stops after initials.[16][17] However, there is a general trend and initiatives to spell out names in full instead of abbreviating them in order to avoid ambiguity.[18][19][20]

Abbreviations

A full stop is used after some abbreviations.[21] If the abbreviation ends a declaratory sentence there is no additional period immediately following the full stop that ends the abbreviation (e.g. "My name is Gabriel Gama Jr."). Though two full stops (one for the abbreviation, one for the sentence ending) might be expected, conventionally only one is written. This is an intentional omission, and thus not haplography, which is unintentional omission of a duplicate. In the case of an interrogative or exclamatory sentence ending with an abbreviation, a question or exclamation mark can still be added (e.g. "Are you Gabriel Gama Jr.?").

Abbreviations and personal titles of address

According to the Oxford A–Z of Grammar and Punctuation, "If the abbreviation includes both the first and last letter of the abbreviated word, as in 'Mister' ['Mr'] and 'Doctor' ['Dr'], a full stop is not used."[22][23] This does not include, for example, the standard abbreviations for titles such as Professor ("Prof.") or Reverend ("Rev."), because they do not end with the last letter of the word they are abbreviating.

In American English, the common convention is to include the period after all such abbreviations.[23]

Acronyms and initialisms

In acronyms and initialisms, the modern style is generally to not use full points after each initial (e.g.: DNA, UK, USSR). The punctuation is somewhat more often used in American English, most commonly with U.S. and U.S.A. in particular. However, this depends much upon the house style of a particular writer or publisher.[24] As some examples from American style guides, The Chicago Manual of Style (primarily for book and academic-journal publishing) deprecates the use of full points in acronyms, including U.S.,[25] while The Associated Press Stylebook (primarily for journalism) dispenses with full points in acronyms except for certain two-letter cases, including U.S., U.K., and U.N., but not EU.[26]

Mathematics

The period glyph is used in the presentation of numbers, either as a decimal separator or as a thousands separator.

In the more prevalent usage in English-speaking countries, as well as in South Asia and East Asia, the point represents a decimal separator, visually dividing whole numbers from fractional (decimal) parts. The comma is then used to separate the whole-number parts into groups of three digits each, when numbers are sufficiently large.

- 1.007 (one and seven thousandths)

- 1,002.007 (one thousand two and seven thousandths)

- 1,002,003.007 (one million two thousand three and seven thousandths)

The more prevalent usage in much of Europe, southern Africa, and Latin America (with the exception of Mexico due to the influence of the United States), reverses the roles of the comma and point, but sometimes substitutes a (thin-)space for a point.

- 1,007 (one and seven thousandths)

- 1.002,007 or 1 002,007 (one thousand two and seven thousandths)

- 1.002.003,007 or 1 002 003,007 (one million two thousand three and seven thousandths)

(To avoid problems with spaces, another convention sometimes used is to use apostrophe signs (') instead of spaces.)

India, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan follow the Indian numbering system, which utilizes commas and decimals much like the aforementioned system popular in most English-speaking countries, but separates values of one hundred thousand and above differently, into divisions of lakh and crore:

- 1.007 (one and seven thousandths)

- 1,002.007 (one thousand two and seven thousandths)

- 10,02,003.007 (one million two thousand three and seven thousandths or ten lakh two thousand three and seven thousandths)

In countries that use the comma as a decimal separator, the point is sometimes found as a multiplication sign; for example, 5,2 . 2 = 10,4; this usage is impractical in cases where the point is used as a decimal separator, hence the use of the interpunct: 5.2 · 2 = 10.4. The interpunct is also used when multiplying units in science - for example, 50 km/h could be written as 50 km·h−1 - and to indicate a dot product, i.e. the scalar product of two vectors.

Logic

In older literature on mathematical logic, the period glyph used to indicate how expressions should be bracketed (see Glossary of Principia Mathematica).

Computing

In computing, the full point, usually called a dot in this context, is often used as a delimiter, such as in DNS lookups, Web addresses, file names and software release versions:

- www.wikipedia.org

- document.txt

- 192.168.0.1

- Chrome 92.0.4515.130

It is used in many programming languages as an important part of the syntax. C uses it as a means of accessing a member of a struct, and this syntax was inherited by C++ as a means of accessing a member of a class or object. Java and Python also follow this convention. Pascal uses it both as a means of accessing a member of a record set (the equivalent of struct in C), a member of an object, and after the end construct that defines the body of the program. In APL it is also used for generalised inner product and outer product. In Erlang, Prolog, and Smalltalk, it marks the end of a statement ("sentence"). In a regular expression, it represents a match of any character. In Perl and PHP, the dot is the string concatenation operator. In the Haskell standard library, it is the function composition operator. In COBOL a full stop ends a statement.

In file systems, the dot is commonly used to separate the extension of a file name from the name of the file. RISC OS uses dots to separate levels of the hierarchical file system when writing path names—similar to / (forward-slash) in Unix-based systems and \ (back-slash) in MS-DOS-based systems and the Windows NT systems that succeeded them.

In Unix-like operating systems, some applications treat files or directories that start with a dot as hidden. This means that they are not displayed or listed to the user by default.

In Unix-like systems and Microsoft Windows, the dot character represents the working directory of the file system. Two dots (..) represent the parent directory of the working directory.

Bourne shell-derived command-line interpreters, such as sh, ksh, and bash, use the dot as a command to read a file and execute its content in the running interpreter. (Some of these also offer source as a synonym, based on that usage in the C-shell.)

Versions of software are often denoted with the style x.y.z (or more), where x is a major release, y is a mid-cycle enhancement release and z is a patch level designation, but actual usage is entirely vendor specific.

Telegraphy

The term STOP was used in telegrams in place of the full stop. The end of a sentence would be marked by STOP; its use "in telegraphic communications was greatly increased during the World War, when the Government employed it widely as a precaution against having messages garbled or misunderstood, as a result of the misplacement or emission [sic] of the tiny dot or period."[27]

In conversation

In British English, the words "full stop" at the end of an utterance strengthen it; they indicate that it admits of no discussion: "I'm not going with you, full stop." In American English the word "period" serves this function.

Another common use in African-American Vernacular English is found in the phrase "And that's on period" which is used to express the strength of the speaker's previous statement, usually to emphasise an opinion.

Linguistics

The International Phonetic Alphabet uses the full stop to signify a syllable break.

Time

In British English, whether for the 12-hour clock or sometimes its 24-hour counterpart, the dot is commonly used and some style guides recommend it when telling time, including those from non-BBC public broadcasters in the UK, the academic manual published by Oxford University Press under various titles,[28] as well as the internal house style book for the University of Oxford,[29] and that of The Economist,[30] The Guardian[31] and The Times newspapers.[32] American and Canadian English mostly prefers and uses colons (:) (i.e., 11:15 PM/pm/p.m. or 23:15 for AmE/CanE and 11.15 pm or 23.15 for BrE),[33] so does the BBC, but only with 24-hour times, according to its news style guide as updated in August 2020.[34] The point as a time separator is also used in Irish English, particularly by the Raidió Teilifís Éireann (RTÉ), and to a lesser extent in Australian, Cypriot, Maltese, New Zealand, South African and other Commonwealth English varieties outside Canada.

Punctuation styles when quoting

The practice in the United States and Canada is to place full stops and commas inside quotation marks in most styles.[35] In the British system, which is also called "logical quotation",[36] full stops and commas are placed according to grammatical sense:[35][37] This means that when they are part of the quoted material, they should be placed inside, and otherwise should be outside. For example, they are placed outside in the cases of words-as-words, titles of short-form works, and quoted sentence fragments.

- Bruce Springsteen, nicknamed "the Boss," performed "American Skin." (closed or American style)

- Bruce Springsteen, nicknamed "the Boss", performed "American Skin". (logical or British style)

- He said, "I love music." (both)

There is some national crossover. The American style is common in British fiction writing.[38] The British style is sometimes used in American English. For example, The Chicago Manual of Style recommends it for fields where comma placement could affect the meaning of the quoted material, such as linguistics and textual criticism.[39][40]

The use of placement according to logical or grammatical sense, or "logical convention", now the more common practice in regions other than North America,[41] was advocated in the influential book The King's English by Fowler and Fowler, published in 1906. Prior to the influence of this work, the typesetter's or printer's style, or "closed convention", now also called American style, was common throughout the world.

Spacing after a full stop

There have been a number of practices relating to the spacing after a full stop. Some examples are listed below:

- One word space ("French spacing"). This is the current convention in most countries that use the ISO basic Latin alphabet for published and final written work, as well as digital media.[42][43]

- Two word spaces ("English spacing"). It is sometimes claimed that the two-space convention stems from the use of the monospaced font on typewriters, but in fact that convention replicates much earlier typography — the intent was to provide a clear break between sentences.[44] This spacing method was gradually replaced by the single space convention in published print, where space is at a premium, and continues in much digital media.[43][45]

- One widened space (such as an em space). This spacing was seen in historical typesetting practices (until the early 20th century).[46] It has also been used in other typesetting systems such as the Linotype machine[47] and the TeX system.[48] Modern computer-based digital fonts can adjust the spacing after terminal punctuation as well, creating a space slightly wider than a standard word space.[49]

Full stops in other scripts

Greek

Although the present Greek full stop (τελεία, teleía) is romanized as a Latin full stop[50] and encoded identically with the full stop in Unicode,[4] the historic full stop in Greek was a high dot and the low dot functioned as a kind of comma, as noted above. The low dot was increasingly but irregularly used to mark full stops after the 9th century and was fully adapted after the advent of print.[4] The teleia should also be distinguished from the ano teleia mark, which is named "high stop" but looks like an interpunct (a middle dot) and principally functions as the Greek semicolon.

Armenian

The Armenian script uses the ։ (վերջակետ, verdjaket). It looks similar to the colon (:).

Chinese and Japanese

In Simplified Chinese and Japanese, a small circle is used instead of a solid dot: "。︀" (U+3002 "Ideographic Full Stop"). Traditional Chinese uses the same symbol centered in the line rather than aligned to the baseline.

Korean

Korean uses the Latin full stop along with its native script.

Nagari

Indo-Aryan languages predominantly use Nagari-based scripts. In the Devanagari script used to write languages like Hindi, Maithili, Nepali, etc., a vertical line । (U+0964 "Devanagari Danda") is used to mark the end of a sentence. It is known as poorna viraam (full stop). In Sanskrit, an additional symbol ॥ (U+0965 "Devanagari Double Danda") is used to mark the end of a poetic verse. However, some languages that are written in Devanagari use the Latin full stop, such as Marathi.

In the Eastern Nagari script used to write languages like Bangla and Assamese, the same vertical line ("।") is used for full-stop, known as Daa`ri in Bengali. Also, languages like Odia and Panjabi (which respectively use Oriya and Gurmukhi scripts) use the same symbol.

Inspired from Indic scripts, the Santali language also uses a similar symbol in Ol Chiki script: ᱾ (U+1C7E "Ol Chiki Punctuation Mucaad") to mark the end of sentence. Similarly, it also uses ᱿ (U+1C7F "Ol Chiki Punctuation Double Mucaad") to indicate a major break, like end of section, although rarely used.

Sinhalese

In Sinhala, a symbol called kundaliya: "෴" (U+0DF4 "Sinhala Punctuation Kunddaliya") was used before the colonial era. Periods were later introduced into Sinhalese script after the introduction of paper due to the influence of European languages.

Southeast Asian

In Burmese script, the symbol ။ (U+104B "Myanmar Sign Section") is used as full stop.

However, in Thai, no symbol corresponding to the full stop is used as terminal punctuation. A sentence is written without spaces and a space is typically used to mark the end of a clause or sentence.

Tibetic

The Tibetan script uses two different full-stops: tshig-grub ། (U+0F0D "Tibetan Mark Shad") marks end of a section of text; don-tshan ༎ (U+0F0E "Tibetan Mark Nyis Shad") marks end of a whole topic. The descendants of Tibetic script also use similar symbols: For example, the Róng script of Lepcha language uses ᰻ (U+1C3B "Lepcha Punctuation Ta-Rol") and ᰼ (U+1C3C "Lepcha Punctuation Nyet Thyoom Ta-Rol").

However, due to influence of Burmese script, the Meitei script of Manipuri language uses ꫰ (U+AAF0 "Meetei Mayek Cheikhan") for comma and ꯫ (U+ABEB "Meetei Mayek Cheikhei") to mark the end of sentence.

Shahmukhi

For Indo-Aryan languages which are written in Nastaliq, like Kashmiri, Panjabi, Saraiki and Urdu, a symbol called k͟hatma (U+06D4 ۔ ARABIC FULL STOP) is used as a full stop at the end of sentences and in abbreviations. It (۔) looks similar to a lowered dash (–).

Ge'ez

In the Ge'ez script used to write Amharic and several other Ethiopian and Eritrean languages, the equivalent of the full stop following a sentence is the ˈarat nettib "።"—which means four dots. The two dots on the right are slightly ascending from the two on the left, with space in between.

Encodings

The character is encoded by Unicode at U+002E . FULL STOP.

There is also U+2E3C ⸼ STENOGRAPHIC FULL STOP, used in several shorthand (stenography) systems.

The character is full-width encoded at U+FF0E . FULLWIDTH FULL STOP. This form is used alongside CJK characters.[51]

In text messages

Researchers from Binghamton University performed a small study, published in 2016, on young adults and found that text messages that included sentences ended with full stops—as opposed to those with no terminal punctuation—were perceived as insincere, though they stipulated that their results apply only to this particular medium of communication: "Our sense was, is that because [text messages] were informal and had a chatty kind of feeling to them, that a period may have seemed stuffy, too formal, in that context," said head researcher Cecelia Klin.[52] The study did not find handwritten notes to be affected.[53]

A 2016 story by Jeff Guo in The Washington Post, stated that the line break had become the default method of punctuation in texting, comparable to the use of line breaks in poetry, and that a period at the end of a sentence causes the tone of the message to be perceived as cold, angry or passive-aggressive.[54]

According to Gretchen McCulloch, an internet linguist, using a full stop to end messages is seen as "rude" by more and more people. She said this can be attributed to the way we text and use instant messaging apps like WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger. She added that the default way to break up one's thoughts is to send each thought as an individual message.[55]

See also

- Decimal separator – Numerical symbol

- Dot (disambiguation)

- Sentence spacing – Horizontal space between sentences in typeset text

- Terminal punctuation – Marks that identify the end of some text

References

- This sentence-ending use, alone, defines the strictest sense of full stop. Although full stop technically applies only when the mark is used to end a sentence, the distinction – drawn since at least 1897[1] – is not maintained by all modern style guides and dictionaries.

- This trend has progressed somewhat more slowly in the English dialect of the United States than in other English language dialects.

- "The Punctuation Points". American Printer and Lithographer. 24 (6): 278. August 1897. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- Williamson, Amelia A. "Period or Comma? Decimal Styles over Time and Place" (PDF). Science Editor. 31 (2): 42–43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-02-28. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- Truss, Lynn (2004). Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation. New York: Gotham Books. p. 25. ISBN 1-59240-087-6.

- Nicolas, Nick. "Greek Unicode Issues: Punctuation Archived August 6, 2012, at archive.today". 2005. Accessed 7 Oct 2014.

- Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd ed. "period, n., adj., and adv." Oxford University Press, 2005,

- "The Workshop: Printing for Amateurs". The Bazaar, Exchange and Mart, and Journal of the Household. 13: 333. 1875-11-06. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- Burchfield, R. W. (2010) [1998]. "full stop". Fowler's Modern English Usage (Revised 3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 317–318. ISBN 978-0-19-861021-2.

- Butterfield, Jeremy (2015). "full stop". Fowler's Dictionary of Modern English Usage (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 331–332. ISBN 978-0-19-966135-0.

- Waddingham, Anne (2014). "4.6: Full point". New Hart's Rules. Oxford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-19-957002-7. Essentially the same text is found in the previous edition under various titles, including New Hart's Rules, Oxford Style Manual, and The Oxford Guide to Style.

- Hart, Horace; et al. (1989) [1983]. Hart's Rules for Compositors and Readers (Corrected 39th ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 2–5, 41, etc. ISBN 0-19-212983-X.

- "A Comparison of the Frequency of Number/Punctuation and Number/Letter Combinations in Literary and Technical Materials" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-11-02. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- Charles F. Meyer (1987). A Linguistic Study of American Punctuation. Peter Lang Publishing, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-8204-0522-3., referenced in Frequencies for English Punctuation Marks Archived 2 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Barden, Cindy (2007), Grammar Grades, vol. 4–5, p. 9,

[…] Use a period after a person's initials. Examples: A. A. Milne […] L.B.Peep W157 […] Use Periods With Initials Name. Initials are abbreviations for parts of a person's name. […] Date: Add periods at the ends of sentences, after abbreviations, and after initials […]

- Blakesley, David; Hoogeveen, Jeffrey Laurence (2007). The Brief Thomson Handbook. p. 477.

[…] Use periods with initials: George W. Bush […] Carolyn B. Maloney […]

- "Full stop". School of critical studies, University of Glasgow. Archived from the original on 2020-07-31. Retrieved 2020-05-02.

- "Instructions for authors". Ecclesiastical Law Journal. 2014-09-04. Archived from the original on 2022-04-10. Retrieved 2020-05-02.

- "Authors Guide-lines for Electronic Submission of MSS to Third Text". Third Text: Critical perspectives on contemporary art and culture. Archived from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2020-05-02.

- Knuth, Donald Ervin (2016). "Let's celebrate everybody's full names". Recent News. Archived from the original on 2018-01-22. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

[…] One of the delights of Wikipedia is that its biographies generally reveal a person's full and complete name, including the correct way to spell it in different alphabets and scripts. […] When I prepared the index […] of The Art of Computer Programming, I wanted to make it as useful as possible, so I spent six weeks compiling all of the entries. In order to relieve the tedium of index preparation, and to underscore the fact that my index was trying to be complete, I decided to include the full name of every author who was cited, whenever possible. […] Over the years, many people have told me how they've greatly appreciated this feature of my books. It has turned out to be a beautiful way to relish the fact that computer science is the result of thousands of individual contributions from people with a huge variety of cultural backgrounds. […] The American Mathematical Society has just launched a great initiative by which all authors can now fully identify themselves […] I strongly encourage everybody to document their full names […]

- Dunne, Edward "Ed" (2015-09-14). "Who wrote that?". AMS Blogs. American Mathematical Society. Archived from the original on 2020-05-24. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- Dunne, Edward "Ed" (2015-11-16). "Personalizing your author profile". AMS Blogs. American Mathematical Society. Archived from the original on 2020-05-04. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- New Hart's Rules: The handbook of style for writers and editors. Oxford University Press, 2005. 2005. ISBN 0-19-861041-6.

- Oxford A–Z of Grammar and Punctuation by John Seely.

- "Punctuation in abbreviations". OxfordDictionaries.com. Oxford University Press. 2017. "Punctuation" section. Archived from the original on 2012-12-17. Retrieved 2017-10-11.

- "Initialisms". OxfordDictionaries.com. Oxford University Press. 2017. "Abbreviations" section. Archived from the original on 2011-12-16. Retrieved 2017-10-11.

- The Chicago Manual of Style, 16th ed.

- "abbreviations and acronyms". The Associated Press Stylebook. 2015. pp. 1–2.

- Ross, Nelson (1928). "HOW TO WRITE TELEGRAMS PROPERLY". The Telegraph Office. Archived from the original on 2013-01-31. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- Anne Waddingham, ed. (2014). "11.3 Times of day". New Hart's rules: the Oxford style guide (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-957002-7.

- "University of Oxford style guide". University of Oxford Public Affairs Directorate. 2016.

- Economist Style Guide (12th ed.). The Economist. 2018. p. 185. ISBN 9781781258316.

- "times". Guardian and Observer style guide. Guardian Media Group. 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-07-09. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- Brunskill, Ian (2017). The Times Style Guide: A guide to English usage (2 ed.). Glasgow: HarperCollins UK. ISBN 9780008146184. OCLC 991389792. Formerly available online: "The Times Online Style Guide". News UK. 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-08-04.

- Trask, Larry (1997). "The Colon". Guide to Punctuation. University of Sussex. Archived from the original on 2013-08-05. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- "BBC News style guide". BBC. Archived from the original on 2022-02-16. Retrieved 2022-04-01.

Numbers... time references... Hours: We use the 24-hour clock (with a colon) in all circumstances (including streaming), labelled GMT or BST as appropriate.

- Lee, Chelsea (2011). "Punctuating Around Quotation Marks". Style Guide of the American Psychological Association. Archived from the original on 2017-03-22. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- "Style Guide" (PDF). Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies. Research Institute of Irish and Scottish Studies, University of Aberdeen. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-04-10. Retrieved 2015-09-15.

Punctuation marks are placed inside the quotation marks only if the sense of the punctuation is part of the quotation; this system is referred to as logical quotation.

- Scientific Style and Format: The CBE Manual for Authors, Editors and Publishers (PDF). Cambridge University Press. 2002. ISBN 9780521471541. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

In the British style (OUP 1983), all signs of punctuation used with words and quotation marks must be placed according to the sense.

- Butcher, Judith; et al. (2006). Butcher's Copy-editing: The Cambridge Handbook for Editors, Copy-editors and Proofreaders. Cambridge University Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-521-84713-1.

- Wilbers, Stephen. "Frequently Asked Questions Concerning Punctuation". Archived from the original on 2018-06-13. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

The British style is strongly advocated by some American language experts. In defense of nearly a century and a half of the American style, however, it may be said that it seems to have been working fairly well and has not resulted in serious miscommunication. Whereas there clearly is some risk with question marks and exclamation points, there seems little likelihood that readers will be misled concerning the period or comma. There may be some risk in such specialized material as textual criticism, but in that case author and editors may take care to avoid the danger by alternative phrasing or by employing, in this exacting field, the exacting British system. In linguistic and philosophical works, specialized terms are regularly punctuated the British way, along with the use of single quotation marks. [quote attributed to Chicago Manual of style, 14th ed.]

- Chicago Manual of Style (15th ed.). University of Chicago Press. 2003. pp. 6.8 – 6.10. ISBN 0-226-10403-6.

According to what is sometimes called the British style (set forth in The Oxford Guide to Style [the successor to Hart's Rules]; see bibliog. 1.1.]), a style also followed in other English-speaking countries, only those punctuation points that appeared in the original material should be included within the quotation marks; all others follow the closing quotation marks. … In the kind of textual studies where retaining the original placement of a comma in relation to closing quotation marks is essential to the author's argument and scholarly integrity, the alternative system described in 6.10 ['the British style'] could be used, or rephrasing might avoid the problem.

- Weiss, Edmond H. (2015). The Elements of International English Style: A Guide to Writing Correspondence, Reports, Technical Documents Internet Pages For a Global Audience. M. E. Sharpe. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7656-2830-5. Retrieved 2016-01-24.

- Einsohn, Amy (2006). The Copyeditor's Handbook: A Guide for Book Publishing and Corporate Communications (2nd ed.). Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-520-24688-1.

- Manjoo, Farhad (2011-01-13). "Space Invaders". Slate. Archived from the original on 2011-05-07. Retrieved 2011-01-19.

- Heraclitus (2011-11-01). "Why two spaces after a period isn't wrong". Archived from the original on 2013-07-26. Retrieved 2013-08-08.

- Felici, James (2003). The Complete Manual of Typography: A Guide to Setting Perfect Type. Berkeley, CA: Peachpit Press. p. 80. ISBN 0-321-12730-7.; Bringhurst, Robert (2004). The Elements of Topographic Style (3.0 ed.). Washington and Vancouver: Hartley & Marks. p. 28. ISBN 0-88179-206-3.

- See for example, University of Chicago Press (1911). Manual of Style: A Compilation of Typographical Rules Governing the Publications of The University of Chicago, with Specimens of Types Used at the University Press (Third ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago. p. 101. ISBN 1-145-26446-8.

- Mergenthaler Linotype Company (1940). Linotype Keyboard Operation: Methods of Study and Procedures for Setting Various Kinds of Composition on the Linotype. Mergenthaler Linotype Company. ASIN B000J0N06M. cited in Simonson, Mark (2004-03-05). "Double-spacing after Periods". Typophile. Typophile. Archived from the original on 2010-01-20. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- Eijkhout, Victor (2014) [1991]. TeX by Topic, A TeXnician's Reference (PDF). Dante; Lehmans Media. pp. 185–188. ISBN 978-3-86541-590-5. First published 1991 by Addison Wesley, Wokingham 978-0-201-56882-0

- Felici, James (2003). The Complete Manual of Typography: A Guide to Setting Perfect Type. Berkeley, CA: Peachpit Press. p. 80. ISBN 0-321-12730-7.; Fogarty, Mignon (2008). Grammar Girl's Quick and Dirty Tips for Better Writing (Quick and Dirty Tips). New York: Holt Paperbacks. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-8050-8831-1.; Straus, Jane (2009). The Blue Book of Grammar and Punctuation: An Easy-to-Use Guide with Clear Rules, Real-World Examples, and Reproducible Quizzes (10th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-470-22268-3.

- Ελληνικός Οργανισμός Τυποποίησης [Ellīnikós Organismós Typopoíīsīs, "Hellenic Organization for Standardization"]. ΕΛΟΤ 743, 2η Έκδοση [ELOT 743, 2ī Ekdosī, "ELOT 743, 2nd ed."]. ELOT (Athens), 2001. (in Greek).

- Lunde, Ken (2009). CJKV Information Processing. O'Reilly. pp. 502–505. ISBN 9780596514471.

- "You Should Watch The Way You Punctuate Your Text Messages – Period". National Public Radio. 2015-12-20. Archived from the original on 2015-12-21. Retrieved 2015-12-20.

- Gunraj, Danielle; Drumm-Hewitt, April; Dashow, Erica; Upadhyay, Sri Siddhi; Klim, Celia (February 2016) [2015], "Texting insincerely: The role of the period in text messaging", Computers in Human Behavior, 55: 1067–1075, doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.003

- Guo, Jeff (June 13, 2016). "Stop. Using. Periods. Period." Archived 2016-06-14 at the Wayback Machine. The Washington Post.

- Morton, Becky (August 2019). "Is the full stop rude?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2019-08-06. Retrieved 2019-08-19.