1886 Atlantic hurricane season

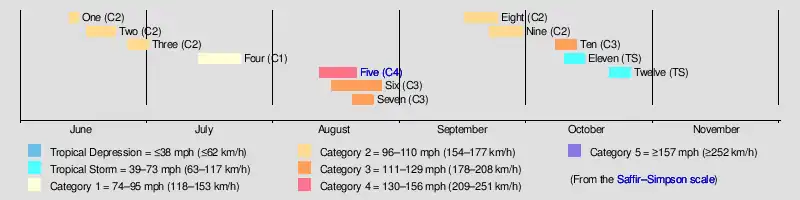

The 1886 Atlantic hurricane season ran through the early summer and the first half of fall in 1886. This is the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. It was a very active year, with ten hurricanes, six of which struck the United States,[1] an event that would not occur again until 1985 and 2020. Four hurricanes became major hurricanes (Category 3+). However, in the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea are known, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 has been estimated.[2] Of the known 1886 cyclones, Hurricane Seven and Tropical Storm Eleven were first documented in 1996 by Jose Fernandez-Partagas and Henry Diaz. They also proposed large alterations to the known tracks of several other 1886 storms.[3]

| 1886 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | June 13, 1886 |

| Last system dissipated | October 26, 1886 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | "Indianola" |

| • Maximum winds | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 925 mbar (hPa; 27.32 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total storms | 12 |

| Hurricanes | 10 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 4 |

| Total fatalities | 200-225 |

| Total damage | ~ $2.25 million (1886 USD) |

Seasonal summary

The 1886 Atlantic hurricane season commenced at 06:00 UTC on June 13.[4][nb 1] The season was approximately average, featuring 12 tropical storms compared to the 1981–2010 annual average of 12.1.[5] The number of hurricanes, however, was well above average, with 10 forming compared to the annual average of 6.4. The number of major hurricanes—defined as Category 3 or higher on the modern Saffir–Simpson scale—was four, compared to an average of 2.7. Owing to deficiencies in surface weather observations at the time, the total number of tropical storms in 1886 was likely higher than 12. A 2008 study indicated that about three storms may have been missed by observational records due to scarce marine traffic over the open Atlantic Ocean.[6] All but two of the storms in 1886 affected land at some point in the tropical stages of their life cycles.[4] Of these, four hurricanes struck the island of Cuba, a record unsurpassed in any Atlantic hurricane season since then.[7] According to the Cuban Meteorological Society, 1886 coincided with a highly active period, 1837–1910, in which one hurricane struck the island every 9.25 years.[8] Additionally, seven hurricanes made landfall in the United States, establishing a record for the number of hurricane strikes in a single season. The years 1886–1887 featured 11 U.S. hurricane landfalls, setting a record for consecutive seasons until 2004–2005, when 12 such storms hit the country.[9] Hurricane activity centered on the Gulf of Mexico: all seven landfalls in 1886 occurred on the U.S. Gulf Coast, with no hurricanes making landfall along the Atlantic Seaboard.[10]

Although other storms may have gone undetected, tropical activity definitely began by the middle of June with the formation of the first named storm over the western Gulf of Mexico on June 13. Two other storms formed before the end of the month and also reached the Gulf of Mexico. The first three storms of the season each attained hurricane intensity and eventually made landfall on the U.S. Gulf Coast with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h).[4] A mid-July storm that formed over the western Caribbean moved northward and struck the west coast of Florida as a hurricane, after two earlier, stronger storms had already done so. Never before or since have so many hurricanes struck Florida in the same season before the month of August.[11] Three storms, all of which attained major hurricane intensity, formed in close succession, over a span of eight days, in August. The first of these, the Indianola hurricane, was the strongest and most intense tropical cyclone of the season, striking multiple islands in the Greater Antilles before rapidly strengthening over the western Gulf of Mexico. It struck the U.S. state of Texas on August 20 with winds of 150 mph (240 km/h), making it one of the strongest hurricanes on record to hit the state.[10] September was a less active month than August, featuring two hurricanes on and just after mid-month. The final hurricane of the year formed in early October and struck Louisiana with winds of 120 mph (190 km/h). Two additional tropical storms occurred in October, with no further activity confirmed afterward.[4]

Systems

Hurricane One

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 13 – June 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); <997 mbar (hPa) |

Early in June, unsettled weather prevailed over the western Caribbean Sea, causing heavy rain and strong winds over Jamaica as early as June 7–8.[12] However, ship reports and data from weather stations first confirmed that a low-pressure area formed off the coast of South Texas.[13][14] Based on the data, HURDAT analyzed that a tropical storm formed about 140 miles (230 km) east-southeast of La Pesca, in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas, on the morning of June 13.[4] Moving generally northward at first, the cyclone quickly intensified through the day as it gradually turned to the north-northeast, paralleling the Texas coast. By 06:00 UTC on June 14, the cyclone already attained hurricane status, and its parabolic path increasingly bent to the northeast. Around 16:00 UTC, the cyclone attained its peak intensity of 100 mph (160 km/h), equivalent to a modern-day Category 2 hurricane, and made landfall just east of High Island, Texas. The cyclone rapidly weakened as it headed inland to the east-northeast, crossing south-central Louisiana as a tropical storm on June 15. Reanalysis in the 1990s determined that it dissipated about 20 miles (32 km) east-southeast of Hattiesburg, Mississippi, by 18:00 UTC on June 15.[4][12]

As it passed just offshore, the hurricane produced strong winds from the east and northeast in Galveston, Texas, generating very high tides. Observers suggested that only the shifting of the winds prevented severe flooding, possibly the worst since a hurricane in 1875; even so, small boats sustained significant damage. Waterfront structures, a tramway, and a railroad were destroyed.[14] Galveston recorded peak winds of 50 mph (80 km/h), and a barometer in town registered a minimum pressure of 29.43 inHg (997 mb);[14] as these conditions were recorded outside the storm's radius of maximum wind, the cyclone was likely stronger.[10] Upon making landfall, the hurricane brought a 7-to-8-foot (2.1 to 2.4 m) storm tide and major flooding to Sabine Pass and its environs.[15] Numerous structures and wharves were destroyed by wind or water,[14] and winds tore roofs from houses. Fruit trees in the area lost much of their fruit.[15] Saltwater intrusion extended several miles inland, imperiling livestock for want of freshwater.[14] Across the state border in adjourning Louisiana, widespread flooding occurred at Calcasieu Pass, where a barge stranded and schooners were wrecked. Half of the corn crop in southwest Louisiana was damaged.[15] While losing intensity so rapidly after landfall that forecasters lost track of it,[14] the storm generated prolific rainfall in its path across Southeast Texas and Louisiana,[12][14] peaking at 21.4 inches (544 mm) in Alexandria, Louisiana.[15]

Hurricane Two

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 17 – June 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); |

Little more than a day after the dissipation of the previous hurricane, a broad area of low pressure over the western Caribbean Sea developed into a tropical storm while centered about 180 miles (290 km) east-southeast of Punta Allen, Quintana Roo, Mexico.[4][12] Over the next two days, the storm meandered toward and through the Yucatán Channel, gradually intensifying as it proceeded to the north-northwest and north. Late on June 18, the system attained hurricane status off the western tip of Pinar del Río Province, Cuba. The following day, the cyclone turned to the north-northeast, producing "severe gales" (47–54 mph, 76–87 km/h) over the waters off Cuba and Jamaica, as reported by ships.[14] At 00:00 UTC on June 20, the storm reached its peak intensity of 100 mph (160 km/h), and shortly afterward its forward speed accelerated. At 11:00 UTC on June 21, the cyclone made landfall a short distance east of St. Marks, Florida, as a Category 2 hurricane.[4] The storm gradually decreased in intensity over the next day and a half as it crossed the Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic states. By 18:00 UTC on June 23, the system passed about 70 miles (110 km) southeast of New York City and curved to the east before dissipating a day later.[4]

Over a six-day period, a long duration of heavy rainfall from the storm caused severe flooding over parts of western Cuba, killing an undetermined number of people in flash floods. Winds over the island were apparently modest, however,[12] though the rain over Vuelta Abajo was the heaviest over a one-week span in 29 years. Several locations were underwater following the deluge.[16] As it passed west of Key West, Florida, the cyclone produced strong southerly winds there. At Cedar Key, gusts of 75–90 mph (121–145 km/h) toppled trees, signage and communications wires, but caused little structural damage.[16] Between there and Apalachicola, above-normal tides covered low-lying streets and pushed ships onshore. Heaviest damages were concentrated in and near Apalachicola and Tallahassee.[11] The storm produced minimal effects in the Jacksonville area, as hurricane-force winds were confined to the west of the Gainesville–Lake City area.[17] The strongest sustained winds measured in Florida were below hurricane force—only 68 mph (109 km/h) at Cedar Key[16]—but "high tides" affected much of the coastline near the point of landfall.[18] Outside Florida, heavy rains, peaking at 5.44 in (138 mm), inundated streets in Lynchburg, Virginia, producing the then-wettest June on record at that place. A daily record for the month, 4.16 in (106 mm), also occurred in Washington, D.C.[19]

In a 1949 report by meteorologist Grady Norton, the U.S. Weather Bureau—later the National Weather Service—considered the storm a "Great Hurricane", implying winds of at least 125 mph (201 km/h),[11][20] though reassessments could find no evidence that the cyclone ever reached major hurricane status.[18]

Hurricane Three

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 27 – July 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); <999 mbar (hPa) |

Closely following the dissipation of the previous storm, yet another tropical storm developed about 90 miles (140 km) west of Negril, Jamaica, at 12:00 UTC on June 27. The system quickly strengthened as it headed north-northwest, acquiring hurricane intensity early the next day. Sharply turning to the west-northwest, the cyclone continued to intensify, reaching its first peak intensity of 90 mph (140 km/h) at 18:00 UTC on June 28. Maintaining force, it struck Pinar del Río Province, Cuba, later that day.[4] On June 29, the cyclone weakened as it crossed western Cuba, but began restrengthening over the eastern Gulf of Mexico as its path turned northwestward. Early on June 30, the hurricane attained its second and strongest peak of 100 mph (160 km/h) as its path began curving to the north. Veering and accelerating to the northeast, the storm struck the Florida Panhandle near Indian Pass around 21:00 UTC that day. The cyclone weakened as it headed inland, losing its identity near Cedartown, Maryland, late on July 2.[4]

In Jamaica, "at least" 18 deaths were attributed to the effects of the storm,[21] and a ship west of the island experienced hurricane-force winds.[16] While described as being of only "moderate intensity", the hurricane caused considerable damage to western Cuba, where homes were destroyed or lost their roofs and trees were prostrated; flooding was reportedly severe as well.[22] Damage was concentrated in and near Batabanó and across Pinar del Río Province. Trece de la Coloma reported a minimum pressure of 29.49 inHg (999 mb). Two drownings occurred when a ship capsized,[16] and an unknown number of fatalities occurred on land in Cuba.[21] In Florida, the eye of the cyclone passed over Apalachicola, which reported top winds of 70 mph (110 km/h). Homes in town lost their roofs, frame buildings collapsed, and several craft in the bay sank, killing some people.[16] At Cedar Key, high tides undermined roadways, and winds of 47–54 mph (76–87 km/h) removed a warehouse from its foundation. Winds gusting to 80 mph (130 km/h) uprooted large trees and moved railroad cars in Tallahassee; one person perished in Jefferson County.[11] "Considerable" destruction of crops occurred in parts of North Florida and adjacent Georgia.[16] Farther north, in North Carolina, winds of 42–44 mph (68–71 km/h) affected Kitty Hawk and Fort Macon, respectively.[23] Copious rains affected southeast Virginia over a two-day span, destroying railroad trestles and embankments. The James River crested 10 feet (3.0 m) above flood stage, flooding waterfront structures in Richmond and prompting evacuations.[19]

Hurricane Four

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 14 – July 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); ≤990 mbar (hPa) |

After nearly two quiet weeks, the fourth tropical storm of the season developed about 105 miles (169 km) west-southwest of George Town, Cayman Islands, at 06:00 UTC on July 14. For two more days, the system drifted west-northwest, gradually strengthening. On July 16, the cyclone began turning to the northeast and accelerated. It reached hurricane status at 12:00 UTC on July 17 and passed just west of Cuba later that day.[4] Its path then bent to the north-northeast, and early the next day, the storm attained its first peak intensity of 80 mph (130 km/h) as its eye neared the west coast of the Florida peninsula. Around 01:00 UTC on July 19, the hurricane made landfall near Ozello, Florida, at that intensity. The storm soon lost hurricane status as it swiftly turned to the east-northeast, briskly crossing North Florida en route to the Atlantic Ocean. At 00:00 UTC on July 20, the storm recovered hurricane status while centered about 140 miles (230 km) south-southeast of Cape Lookout, North Carolina, and six hours later attained its second and strongest peak of 85 mph (137 km/h). The storm acquired extratropical characteristics early on July 23, and after curving to the northeast over the far north Atlantic, it dissipated at 18:00 UTC on July 24.[4]

Although it bypassed the island to the west, the cyclone generated heavy rains over western Cuba throughout July 16–17,[24] causing rivers to overflow their banks.[25] An anemometer in Key West measured top winds of 52 mph (84 km/h) during the passage of the hurricane, with no damage to shipping in the harbor. A few schooners were forced to shelter in safe harbor overnight.[25] Overall damage near the point of landfall in Florida was slight, as the area was thinly inhabited. Off the Atlantic coast of the Southeastern United States, the storm interrupted maritime traffic.[11] Multiple ships in the path of the storm recorded hurricane-force winds; the lowest pressure reported dipped to 29.23 inHg (990 mb).[26]

Hurricane Five

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 12 – August 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min); 925 mbar (hPa) |

The Indianola Hurricane of 1886

A tropical storm developed east of Trinidad and Tobago on August 12 and began moving northwestward. Originally it was thought the storm became a Category 1 hurricane the next day but re-analysis now shows it remained as a tropical storm until August 14.[27] On the evening of August 15 it reached the island of Hispaniola. After crossing the south of that island as a Category 1 hurricane, it struck southeastern Cuba on August 16 as a Category 2 hurricane.[27] The storm briefly weakened whilst over land and entered the Gulf of Mexico near Matanzas on August 18 as a Category 1 storm. As the hurricane crossed the Gulf of Mexico it strengthened further, first to a Category 2 then to a Category 3 cyclone. As it approached the coast of Texas, it had intensified to a 150 mph (240 km/h) Category 4 hurricane.

On August 20, it made landfall as a category 4 hurricane at that strength with catastrophic results. At Indianola, Texas a storm surge of 15 feet overwhelmed the town. Every building in the town was either destroyed or left uninhabitable. When the Signal Office there was blown down, a fire started which took hold and destroyed several neighboring blocks. The village of Quintana, at the mouth of the Brazos River was also destroyed.[28] At Houston the bayou rose between 5–6 feet on August 19. Bridges were overrun by flood water and trees blown over at Galveston. Offshore several ships were wrecked there.[28] Since the town of Indianola was destroyed, it was abandoned and never rebuilt. After making landfall, the storm eventually dissipated on August 21 in the northwest corner of Texas.

Hurricane Six

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 15 – August 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min); ≤977 mbar (hPa) |

The Cuba Hurricane of 1886

On August 15 a hurricane was seen 90 miles northeast of Barbados. On August 16 it passed over the island of Saint Vincent as Category 2 hurricane. The hurricane passed north of Grenada and continued westward towards the coast of Venezuela, bringing a heavy gale, and some damage, to Curaçao before curving north. Around midnight on August 19 it hit Jamaica, still at Category 2 intensity. The island experienced winds of 110 mph (180 km/h) throughout August 19 and 20th. The hurricane approached the south coast of Cuba as a major Category 3 hurricane on August 21. It crossed Cuba over the central province of Ciego de Ávila before exiting the island near Moron on the north coast. The hurricane then passed over Nassau on the night of August 22. It quickly moved northeastward, and travelled parallel to the east coast of the United States, still at Category 2 intensity, before it weakened and dissipated south of Newfoundland on the August 27.[3] Damage was extensive at several of the locations impacted by the hurricane and some fatalities occurred on St. Vincent, Jamaica and possibly Cuba. Throughout the south of St Vincent, damage was extensive with many injuries and some fatalities reported. Thousands of trees were blown down and 300 homes destroyed on the island. At Jamaica crops and plantations were destroyed and some ships wrecked in Kingston harbour. In Cuba hundreds of homes were blown down, many trees were uprooted and some areas flooded. In the Bahamas, several sailing ships were blown ashore, both at Nassau and at Andros and at the Berry Islands.[3]

Hurricane Seven

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 20 – August 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min); ≤962 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm formed west of Bermuda on August 20. It passed about 175 miles to the south of the island before turning northwestward. As the storm travelled north on August 21, it intensified to a 115 mph (185 km/h) Category 3 hurricane. It reached the area of Georges Bank at that intensity on August 22 and damaged several vessels there.[3] On August 23 it weakened to a Category 1 hurricane and became an extratropical storm on August 24 near the Grand Banks.

Hurricane Eight

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 16 – September 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); 973 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm formed north of Puerto Rico on September 16. It travelled west, passing north of Hispaniola on September 17 and crossing Cuba in the Las Tunas region on September 18. The next day the storm passed just south of Isla de la Juventud and continued westward before curving north into the Gulf of Mexico. As the storm travelled north, parallel to the east coast of Mexico, it intensified to a 100 mph (160 km/h) Category 2 hurricane. The hurricane maintained this intensity until it made landfall just south of the Mexico–United States border early on September 23. After crossing into Texas, the system quickly weakened and dissipated the next day to the southeast of Austin.[4] Heavy rainfall was recorded, including about 26 in (660 mm) at Brownsville between September 21 and September 23. Two hundred houses were blown down there.[3] Only five weeks after the devastation brought by Hurricane Five, Indianola was again flooded by rainwater and storm surge from Matagorda Bay. The remaining residents were evacuated. Following this storm the post office at Indianola was shut down, marking the official abandonment of the town.[28]

Hurricane Nine

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 22 – September 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); ≤990 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm formed in the western Atlantic on September 22. Within two days it had grown to a Category 2 hurricane with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h). The storm maintained this intensity for six days until September 30, when it weakened to first a Category 1 hurricane then to a tropical storm. The cyclone never made landfall but is known from several ship reports. Most notable are those from the bark Mary, which endured the storm from September 22 until the 28th, and that of the brigantine Pearl which, on the evening of September 25, recorded sightings of ball lighting and "St. Elmo's light at the yard-arms" during the storm.[3]

Hurricane Ten

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 8 – October 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min); 955 mbar (hPa) |

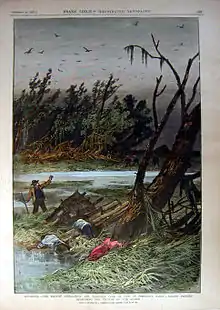

The Texas–Louisiana Hurricane of 1886

A tropical storm was observed in the northwest Caribbean on October 8. It moved to the northwest, reaching major hurricane strength in the Gulf of Mexico on October 11. Late on October 12, the hurricane made landfall as a category 3 hurricane near the border between Louisiana and Texas. It caused between 126 and 150 deaths in the East Texas area.[29] due to the heavy rainfall and storm surge, with $250,000 in damage occurring. Port Eads, Louisiana and parts of New Orleans were reported to be flooded.[3] Sabine Pass, Texas was all but destroyed. On the afternoon of October 12 wind speeds there reached 100 mph (160 km/h) and waves from the Gulf were 20 feet high. Most buildings in the town were destroyed and ten miles of railroad track damaged. Numerous vessels were washed miles inshore and wrecked. At Johnson Bayou, Louisiana most buildings in the town were destroyed, and many residents drowned, by the impact of a seven-foot storm surge which extended twenty miles inland. At least 196 people died as a result of the storm.[30]

Tropical Storm Eleven

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 10 – October 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical storm existed in the western Atlantic between October 10 and October 15. It reached a peak wind speed of 50 mph (80 km/h) throughout October 13 and 14. It is thought that the existence of this storm may have been responsible for the westward deviation taken by Hurricane Ten in the Gulf of Mexico on October 10.[3]

Tropical Storm Twelve

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 21 – October 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); ≤992 mbar (hPa) |

Several ships reported a large, but weak, tropical storm in the Caribbean Sea, south of Haiti on October 22.[3] It is thought the storm had actually formed the previous day. After crossing Haiti on October 22 the storm continued moving northeastward into the Atlantic. The storm maintained a peak wind speed of 70 mph (110 km/h) throughout October 23 and 24. It weakened on October 25 and dissipated on October 26 in the mid-Atlantic.

See also

Notes

- All dates denoting individual storms' life cycles are based on UTC unless otherwise noted.

References

- Hurricane Research Division (2008). "Chronological List of All Hurricanes which Affected the Continental United States: 1851-2007". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- Landsea, C. W. (2004). "The Atlantic hurricane database re-analysis project: Documentation for the 1851–1910 alterations and additions to the HURDAT database". In Murname, R. J.; Liu, K.-B. (eds.). Hurricanes and Typhoons: Past, Present and Future. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 177–221. ISBN 0-231-12388-4.

- Partagas, J.F. and H.F. Diaz, 1996a "A reconstruction of historical Tropical Cyclone frequency in the Atlantic from documentary and other historical sources Part III: 1881–1890" Climate Diagnostics Center, NOAA, Boulder, Colorado

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Background Information: the North Atlantic Hurricane Season". National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 6 August 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- Vecchi, Gabriel A.; Knutson, Thomas R. (July 2008). "On Estimates of Historical North Atlantic Tropical Cyclone Activity". Journal of Climate. 21 (14): 3588–3591. Bibcode:2008JCli...21.3580V. doi:10.1175/2008JCLI2178.1.

- Pérez Suárez, R.; Vega, R.; Limia, M. (2000). Los ciclones tropicales de Cuba, su variabilidad y su posible vinculación con los Cambios Globales (Report) (in Spanish). Instituto de Meteorología.

- "Los ciclones tropicales que han afectado a las provincias de Ciudad de la Habana y la Habana". Boletín de SOMETCUBA (in Spanish). Sociedad Meteorológica de Cuba. 6 (1). January 2000. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- Blake, Eric S.; Ethan J. Gibney (August 2011). The Deadliest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones from 1851 to 2010 (and Other Frequently Requested Hurricane Facts) (PDF) (Technical report). National Weather Service, National Hurricane Center. pp. 16–17. NWS NHC-6. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- Landsea, Chris; Anderson, Craig; Bredemeyer, William; et al. (January 2022). Continental United States Hurricanes (Detailed Description). Re-Analysis Project (Report). Miami, Florida: Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

- Barnes, Jay (1998). Florida's Hurricane History (1st ed.). Chapel Hill: UNC Press. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-8078-4748-8.

- Partagás, J. F.; Díaz, H. F. (1996). "A Reconstruction of Historical Tropical Cyclone Frequency in the Atlantic from Documentary and other Historical Sources, Part III: 1881–1890". Year 1886 (PDF) (Report). Climate Diagnostics Center. pp. 36–37. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- "Chart I. Tracks of Areas of Low Pressure. June, 1886" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 14 (6): C1. June 1886. Bibcode:1886MWRv...14Y...1.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1886)146[c1:CITOAO]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- "Atmospheric Pressure" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 14 (6): 149. June 1886. Bibcode:1886MWRv...14R.147.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1886)14[147b:AP]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- David M. Roth (13 January 2010). Louisiana Hurricane History (PDF) (Report). National Weather Service Southern Region Headquarters. pp. 23–24. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- MWR 1886a, p. 150

- Al Sandrik & Chris Landsea (2003). "Chronological Listing of Tropical Cyclones affecting North Florida and Coastal Georgia 1565-1899". Hurricane Research Division. Archived from the original on December 6, 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-02.

- Partagás & Díaz 1996, p. 38

- Roth, David; Cobb, Hugh (16 July 2001). "Late Nineteenth Century Virginia Hurricanes, 1851–1900". Virginia Hurricane History. Hydrometeorological Prediction Center, National Weather Service. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- Williams, John M.; Duedall, Iver W. (2002). Florida Hurricanes and Tropical Storms, 1871–2001 (2nd ed.). Gainesville: University Press of Florida. p. 86. ISBN 0-8130-2494-3.

- Rappaport, Edward N.; Fernández-Partagás, José (22 April 1997) [28 May 1995]. "Appendix 2: Cyclones that may have 25+ deaths". The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492–1996 (Technical report). National Weather Service, National Hurricane Center. NWS NHC 47.

- Partagás & Díaz 1996, p. 39

- "Atmospheric Pressure" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 14 (7): 176–177. July 1886. Bibcode:1886MWRv...14R.175.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1886)14[175b:AP]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- Partagás & Díaz 1996, p. 42

- MWR 1886b, p. 178

- "North Atlantic Storms During July, 1886" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 14 (7): 181. July 1886. Bibcode:1886MWRv...14..179.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1886)14[179:NASDJ]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- Hurricane Research Division (2008). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2011-03-14.

- David Roth (2010-02-04). "Texas Hurricane History" (PDF). National Weather Service. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- Edward N. Rappaport & Jose Fernandez-Partagas (1996). "The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492–1996: Cyclones with 25+ deaths". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-03-14.

- W. T. Block (October 10, 1979). "October 12, 1886: The Night That Johnson's Bayou, Louisiana Died". The Beaumont Enterprise. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

External links

Unisys Data for 1886 Atlantic Hurricane Season: 1886 Hurricane/Tropical Data for Atlantic