1956 Summer Olympics

The 1956 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XVI Olympiad, were an international multi-sport event held in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, from 22 November to 8 December 1956, with the exception of the equestrian events, which were held in Stockholm, Sweden, in June 1956.

Emblem of the 1956 Summer Olympics | |

| Host city | Melbourne, Australia / Stockholm, Sweden |

|---|---|

| Nations | 72 |

| Athletes | 3,314 (2,938 men, 376 women) |

| Events | 151 in 17 sports (23 disciplines) |

| Opening | 22 November 1956 |

| Closing | 8 December 1956 |

| Opened by | |

| Cauldron | |

| Stadium | Melbourne Cricket Ground |

Summer

Winter

| |

| Part of a series on |

| 1956 Summer Olympics |

|---|

|

These Games were the first to be staged in the Southern Hemisphere and Oceania, as well as the first to be held outside Europe and North America. Melbourne is the most southerly city ever to host the Olympics. Due to the Southern Hemisphere's seasons being different from those in the Northern Hemisphere, the 1956 Games did not take place at the usual time of year, because of the need to hold the events during the warmer weather of the host's spring/summer (which corresponds to the Northern Hemisphere's autumn/winter), resulting in the only summer games ever to be held in November and December. Australia hosted the Games for a second time in 2000 in Sydney, New South Wales, and will host them again in 2032 in Brisbane, Queensland.

The Olympic equestrian events could not be held in Melbourne due to Australia's strict quarantine regulations,[2] so they were held in Stockholm five months earlier. This was the second time the Olympics were not held entirely in one country, the first being the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp, Belgium, with some events taking place in Ostend, Belgium and Amsterdam, Netherlands. Despite uncertainties and various complications encountered during the preparations, the 1956 Games went ahead in Melbourne as planned and turned out to be a success. Started during the 1956 Games was the "Parade of Athletes" at the closing ceremonies.

Eight teams boycotted the Games for various reasons.[3] Four teams (Egypt, Iraq, Cambodia and Lebanon) boycotted in response to the Suez Crisis, in which Egypt was invaded by Israel, France and the United Kingdom.[4][5] Three teams (the Netherlands, Spain and Switzerland) boycotted in response to the Soviet invasion of Hungary,[5][6] and the People's Republic of China's boycott was in response to a dispute with the Republic of China over the right to represent China.[7][8]

The Soviet Union won the most gold medals, and the most medals overall.

One of the most notable events of the games was a controversial water polo match between the Soviet Union and the defending champions, Hungary. The Soviet Union had recently suppressed an anti-Soviet revolution in Hungary and violence broke out between the teams during the match, resulting in numerous injuries. When Ervin Zádor suffered bleeding after being punched by Valentin Prokopov, spectators attempted to join the violence, but they were blocked by police. The match was cancelled, with Hungary being declared the winner because they were in the lead.

Host city selection

Melbourne was selected as the host city over bids from Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Montreal, Los Angeles, Detroit, Chicago, Minneapolis, Philadelphia, and San Francisco at the 43rd IOC Session in Rome, Italy on 28 April 1949. Mexico City, Montreal and Los Angeles would eventually be selected to host the 1968, 1976 and 1984 Summer Olympics.[9]

| City | Country | Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | Round 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melbourne | 14 | 18 | 19 | 21 | |

| Buenos Aires | 9 | 12 | 13 | 20 | |

| Los Angeles | 5 | 4 | 5 | — | |

| Detroit | 2 | 4 | 4 | — | |

| Mexico City | 9 | 3 | — | — | |

| Chicago | 1 | — | — | — | |

| Minneapolis | 1 | — | — | — | |

| Philadelphia | 1 | — | — | — | |

| San Francisco | 0 | — | — | — | |

| Montreal | 0 | — | — | — |

Prelude

Many members of the IOC were sceptical about Melbourne as an appropriate site. Its location in the Southern Hemisphere was a major concern since the reversal of seasons would mean the Games must be held during the northern winter. The November–December schedule was thought likely to inconvenience athletes from the Northern Hemisphere, who were accustomed to resting during their winter.

Notwithstanding these concerns, the field of candidates eventually narrowed to two Southern Hemisphere cities, these being Melbourne and Buenos Aires, Argentina. Melbourne was selected, in 1949, to host the 1956 Olympics by a one-vote margin. The first sign of trouble was the revelation that Australian equine quarantine would prevent the country from hosting the equestrian events.[2] Stockholm was selected as the alternative site, so equestrian competition began on 10 June, five and a half months before the rest of the Olympic Games were to open.

The above problems of the Melbourne Games were compounded by bickering over financing among Australian politicians. Eventually, in March 1953, the State Government accepted a £2 million loan from the Commonwealth Government to build the Olympic Village, which would accommodate up to 6,000 people, in Heidelberg West. After the Olympics, the houses in the village were handed back to the Housing Commission for general public housing.[11]

At one point, IOC President Avery Brundage suggested that Rome, which was to host the 1960 Games, was so far ahead of Melbourne in preparations that it might be ready as a replacement site in 1956. Construction of sporting venues was given priority over the athlete's village.[12] The village was designed as a whole new suburb with semi-detached houses and flats. For the first time both sexes were to reside in the same buildings, separated only by fence.[12]

As late as April 1955, Brundage was still doubtful about Melbourne and was not satisfied by an inspection trip to the city. Construction was well under way by then, thanks to a $4.5 million federal loan to Victoria, but it was behind schedule. He still held out the possibility that Rome might have to step in.

By the beginning of 1956, though, it was obvious that Melbourne would be ready for the Olympics.[13]

Participation and boycotts

_boycotting_countries_(blue).png.webp)

Egypt, Iraq, Cambodia and Lebanon announced that they would not participate in the Olympics in response to the Suez Crisis when Egypt was invaded by Israel, the United Kingdom, and France.

The Netherlands, Spain and Switzerland boycotted the event in protest at the Soviet Union presence in light of their recent crushing of the Hungarian Revolution.

The People's Republic of China chose to boycott the event because the Republic of China had been allowed to compete.

Although the number of countries participating (67) was almost the same as in 1952 (69), the number of athletes competing dropped sharply, from 4,925 to 3,342. (This figure does not include the 158 athletes from 29 countries who took part in the Stockholm equestrian competition.)

Events

Once underway, the Games progressed smoothly, and came to be known as the "Friendly Games".[12] Betty Cuthbert, an 18-year-old from Sydney, won the 100 and 200 metre sprint races and ran an exceptional final leg in the 4 x 100 metre relay to overcome Great Britain's lead and claim her third gold medal. The veteran Shirley Strickland repeated her 1952 win in the 80 metre hurdles and was also part of the winning 4 x 100 metre relay team, bringing her career Olympic medal total to seven: three golds, a silver, and three bronze medals.

Australia also triumphed in swimming. They won all of the freestyle races, men's and women's, and collected a total of eight gold, four silver and two bronze medals. Murray Rose became the first male swimmer to win two freestyle events since Johnny Weissmuller in 1924, while Dawn Fraser won gold medals in the 100 metre freestyle and as the leadoff swimmer in the 4 x 100 metre relay team.

The men's track and field events were dominated by the United States. They not only won 15 of the 24 events, they swept four of them and took first and second place in five others. Bobby Morrow led the way with gold medals in the 100 and 200 metre sprints and the 4 x 100 metre relay. Tom Courtney barely overtook Great Britain's Derek Johnson in the 800 metre run, then collapsed from the exertion and needed medical attention.

Ireland's Ronnie Delany ran an outstanding 53.8 over the last 400 metres to win the 1,500 metre run, in which favourite John Landy of Australia finished third.

There was a major upset, marred briefly by controversy, in the 3,000 metre steeplechase. Little-known Chris Brasher of Great Britain finished well ahead of the field, but the judges disqualified him for interfering with Norway's Ernst Larsen, and they announced Sándor Rozsnyói of Hungary as the winner. Brasher's appeal was supported by Larsen, Rozsnyói, and fourth-place finisher Heinz Laufer of Germany. Subsequently, the decision was reversed and Brasher became the first Briton to win a gold medal in track and field since 1936.

Only two world records were set in track and field. Mildred McDaniel, the first American woman to win gold in the sport, set a high jump record of 1.76 metres (5.8 ft), and Egil Danielsen of Norway overcame blustery conditions with a remarkable javelin throw of 85.71 metres (281.2 ft).

Throughout the Olympics, Hungarian athletes were cheered by fans from Australia and other countries. Many of them gathered in the boxing arena when thirty-year-old Laszlo Papp of Hungary won his third gold medal by beating José Torres for the light-middleweight championship.

A few days later, the crowd was with the Hungarian water polo team in its match against the Soviet Union which took place against the background of the Soviet invasion of Hungary. The game became rough and, when a Hungarian was forced to leave the pool with a bleeding wound above his eye, a riot almost broke out. The police restored order and the game was called early, with Hungary leading 4–0, and the Hungarians went on to win the gold medal.

In a much publicized Olympic romance, American hammer throw champion Hal Connolly would marry Czechoslovak discus throw champion, Olga Fikotová. After moving to the United States, Olga wanted to continue representing Czechoslovakia, but the Czechoslovak Olympic Committee would not allow her to do so.[14] Thereafter, as Olga Connolly, she took part in every Olympics until 1972[14] competing for the U.S.[15] She was the flag bearer for the U.S. team at the 1972 Summer Olympics.

Despite the international tensions of 1956—or perhaps because of them—a young Melburnian, John Ian Wing, came up with a new idea for the closing ceremony. Instead of marching as separate teams, behind their national flags, the athletes mingled together as they paraded into and around the arena for a final appearance before the spectators. It was the start of an Olympic tradition that has been followed ever since.[16]

Highlights

- These were the first Summer Olympic Games under the IOC presidency of Avery Brundage.

- Hungary and the Soviet Union (who were engaged in an armed conflict at the time) were both present at the Games which, among other things, led to a hotly contested and emotionally charged water polo encounter between the two nations.

- Athletes from both East and West Germany competed together as a combined team, a remarkable display of unity that was repeated in 1960 and 1964, but was then discontinued.

- Australian athlete Betty Cuthbert became the "Golden Girl" by winning three gold medals in track events. Another Australian, Murray Rose, won three gold medals in swimming.

- U.S. sprinter Bobby Morrow won three gold medals, in the 100m and 200m sprints, and the 4 × 100 m relay.

- Soviet runner Vladimir Kuts won both the 5,000-metre and 10,000-metre events.

- Inspired by Australian teenager John Ian Wing, an Olympic tradition began when athletes from different nations were allowed to parade together at the closing ceremony, rather than separately with their national teams, as a symbol of world unity.

- During the Games there will be only one nation. War, politics and nationalities will be forgotten. What more could anybody want if the world could be made one nation.

—Extract from a letter by John Wing to the Olympic organisers, 1956

- During the Games there will be only one nation. War, politics and nationalities will be forgotten. What more could anybody want if the world could be made one nation.

- Laszlo Papp defended his light-middleweight boxing title, gaining a record third Olympic gold medal.

- Ronnie Delany won gold for Ireland in the 1,500m final, the last Olympic gold medal that Ireland has won in a track event.

- The India men's national field hockey team won its sixth consecutive Olympic gold.

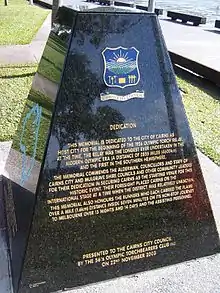

Olympic torch relay

The Olympic flame was relayed to Melbourne after being lit at Olympia on 2 November 1956.

- Greek runners took the flame from Olympia to Athens.

- The flame was transferred to a miner's lamp, then flown by a Qantas Super Constellation aircraft, "Southern Horizon" to Darwin, Northern Territory.

- A Royal Australian Air Force English Electric Canberra jet bomber transported the flame to Cairns, Queensland, where it arrived on 9 November 1956.

- The Mayor of Cairns, Alderman W.J. Fulton, lit the first torch.

- The torch design was identical to the one used for the 1948 London Games (except for the engraved city name and year).

- The first runner was Con Verevis, a local man of Greek parentage.

- The flame was relayed down the east coast of Australia using die cast aluminium torches weighing about 3 pounds (1.8 kg).

- The flame arrived in Melbourne on 22 November 1956, the day of the opening ceremony.

- The flame was lit at the Olympic stadium by Ron Clarke, who accidentally burned his arm in the process.

While the Olympic flame was being carried to Sydney, an Australian veterinary student named Barry Larkin carried a fake Olympic Flame and fooled the mayor of Sydney.[17]

Television

The Olympics were first televised during the 1936 games to a domestic audience in Berlin. The 1956 Winter Olympics in Cortina d'Ampezzo were broadcast internationally with the organising committee giving the television rights for free.[18] While there was much interest in the games overseas, no international television or newsreel rights were awarded, as the Melbourne organising committee requested licensing payments for the broadcasting rights.[18][19] However, domestic rights to the games were hastily agreed by the three Melbourne stations at the time, GTV9, HSV7 and ABV2, only a week before the opening ceremony.[19][20] The three Sydney stations, TCN9, ATN7 and ABN2, syndicated the Melbourne coverage. With television in Australia having its beginnings in September 1956, for many Australians, their first glimpse of television was Olympic broadcasts.[21] As only around five thousand televisions had been sold by the time of the Games, the Australian audience largely watched the games at community halls and at Ampol petrol stations.[20]

Sports

The 1956 Summer Olympics featured 17 different sports encompassing 23 disciplines, and medals were awarded in 151 events (145 events in Melbourne and 6 equestrian events in Stockholm).[22] In the list below, the number of events in each discipline is noted in parentheses.

- Aquatics

Diving (4)

Diving (4) Swimming (13)

Swimming (13) Water polo (1)

Water polo (1)

Athletics (33)

Athletics (33) Basketball (1)

Basketball (1) Boxing (10)

Boxing (10)_pictogram.svg.png.webp) Canoeing (9)

Canoeing (9)_pictogram.svg.png.webp) Cycling

Cycling

- Road (2)

- Track (4)

Equestrian

Equestrian

- Dressage (2)

- Eventing (2)

- Show jumping (2)

Fencing (7)

Fencing (7) Association football (1)

Association football (1)_pictogram.svg.png.webp) Gymnastics (15)

Gymnastics (15) Field hockey (1)

Field hockey (1) Modern pentathlon (2)

Modern pentathlon (2) Rowing (7)

Rowing (7) Sailing (5)

Sailing (5) Shooting (7)

Shooting (7) Weightlifting (7)

Weightlifting (7) Wrestling

Wrestling

- Freestyle (8)

- Greco-Roman (8)

Demonstration sports

Australian football (1)

Australian football (1)  Baseball (1)

Baseball (1)

Venues

.jpg.webp)

- Ballarat

- Lake Wendouree – Canoeing, Rowing

- Melbourne

- Broadmeadows – Cycling (road)

- Hockey Field – Field hockey

- Melbourne Cricket Ground – Athletics, Field hockey (final), Football (final)

- Oaklands Hunt Club – Modern pentathlon (riding, running)

- Olympic Park Stadium – Football

- Port Phillip Bay – Sailing

- Royal Australian Air Force, Laverton Air Base – Shooting (shotgun)

- Royal Exhibition Building – Basketball (final), Modern pentathlon (fencing), Weightlifting, Wrestling

- St Kilda Town Hall – Fencing

- Swimming/Diving Stadium (Olympic Pool) – Diving, Modern pentathlon (swimming), Swimming, Water polo

- Velodrome – Cycling (track)

- West Melbourne Stadium – Basketball, Boxing, Gymnastics

- Williamstown – Modern pentathlon (shooting), Shooting (pistol, rifle)

- Stockholm

- Lill-Jansskogen – Equestrian (eventing)

- Olympic Stadium – Equestrian (dressage, eventing, jumping)

- Ulriksdal – Equestrian (eventing)

Participating National Olympic Committees

A total of 67 nations competed in the 1956 Olympics. Eight countries made their Olympic debuts: Cambodia (only competed in the equestrian events in Stockholm), Ethiopia, Fiji, Kenya, Liberia, Federation of Malaya, North Borneo (modern-day Sabah of Malaysia), and Uganda. Athletes from East Germany and West Germany competed together as the United Team of Germany, an arrangement that would last until 1968.

For the first time, the team of Republic of China effectively represented only Taiwan.

Five nations competed in the equestrian events in Stockholm, but did not attend the Games in Melbourne. Cambodia, Egypt and Lebanon did not compete in Melbourne due to a boycott regarding the Suez Crisis, whilst the Netherlands, Spain and Switzerland all boycotted the Melbourne Olympics in protest at the Soviet invasion of Hungary.[23]

Number of athletes by National Olympic Committees

Medal count

These are the top ten nations that won medals at the 1956 Games.

| Rank | Nation | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 37 | 29 | 32 | 98 | |

| 2 | 32 | 25 | 17 | 74 | |

| 3 | 13 | 8 | 14 | 35 | |

| 4 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 26 | |

| 5 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 25 | |

| 6 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 19 | |

| 7 | 6 | 13 | 7 | 26 | |

| 8 | 6 | 7 | 11 | 24 | |

| 9 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 13 | |

| 10 | 4 | 10 | 5 | 19 | |

| Totals (10 entries) | 128 | 118 | 113 | 359 | |

- Key

* Host nation (Australia). John Ian Wing of Australia was also presented with a bronze medal, not included in the above table, for suggesting the closing ceremony have athletes as one nation.[24]

See also

- 1956 Winter Olympics

- Olympic Games celebrated in Australia

- 1956 Summer Olympics – Melbourne

- 2000 Summer Olympics – Sydney

- 2032 Summer Olympics – Brisbane

Notes

- The Duke of Edinburgh did not regain the title "Prince" until the following year. See List of titles and honours of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

References

- "Factsheet – Opening Ceremony of the Games of the Olympiad" (PDF) (Press release). International Olympic Committee. 13 September 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- Tarbotton, David (12 November 2016). "Melbourne 1956 makes history as equestrian events take place in Sweden". Australian Olympic Committee. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- "Melbourne 1956 Summer Olympics - Athletes, Medals & Results". 24 April 2018.

- Kaufman, Burton I.; Kaufman, Diane (6 October 2009). The A to Z of the Eisenhower Era. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0810870635.

- "6 Times the Olympics Were Boycotted - disapproval over wars, invasions...", history.com, 2021-07-26

- Hungary Today: "Hungary Hails Veteran Athletes Who Boycotted The 1956 Melbourne Olymipc Games Out Of Solidarity With Hungary", 2016-11-22

- The Times, "The Latest Threat to the Olympics - And its all over a name", 10 July 1976

- Chinese Olympics Committee website

- "Ioc Vote History". Aldaver.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2008. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- "Past Olympic host city election results". GamesBids. Archived from the original on 24 January 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- Reeves, Debra. "The 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne". Parliament of Victoria. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- Lucas, Cade (28 July 2016). "The mixed fortunes of Melbourne's 1956 Olympic venues, 60 years on". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- Wendy Lewis, Simon Balderstone and John Bowan (2006). Events That Shaped Australia. New Holland. pp. 212–217. ISBN 978-1-74110-492-9.

- Duguid, Sarah (9 June 2012). "The Olympians: Olga Fikotová, Czechoslovakia". Financial Times Magazine. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- Evans, Hilary; Gjerde, Arild; Heijmans, Jeroen; Mallon, Bill; et al. "Pat McCormick". Olympics at Sports-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020.

- Text of John Ian Wing's letter, page found 28 June 2011.

- Turpin, Adrian (8 August 2004). "Olympics Special: The Lost Olympians (Page 1)". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 April 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2008.

- "Olympic Broadcasting Through The Years (2008 - 1924)" (PDF). Olympic Broadcasting Services. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- Goldblatt, David (2018). The games : a global history of the Olympics (Paperback ed.). London. pp. Chapter 9. ISBN 978-1447298878.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bayley, Andrew (24 February 2014). "Thursday 22 November 1956 — MELBOURNE". Television.AU. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Wildman, Kim; Hogue, Derry (2015). First Among Equals: Australian Prime Ministers from Barton to Turnbull. Wollombi, NSW: Exisle Publishing. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-77559-266-2.

- IOC site for the 1956 Olympic Games

- "Melbourne – Stockholm 1956: (ALL FACTS)". IOC. 24 April 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- Chappell, Bill (8 August 2021). "Why the Olympic Athletes Don't March Behind Their Own Flag at the Closing Ceremony". NPR.

External links

| External video | |

|---|---|

- "Melbourne - Stockholm 1956". Olympics.com. International Olympic Committee.