1982 World's Fair

The 1982 World's Fair, officially known as the Knoxville International Energy Exposition (KIEE) and simply as Energy Expo '82 and Expo '82, was an international exposition held in Knoxville, Tennessee, United States. Focused on energy and electricity generation, with the theme Energy Turns the World, it was officially registered as a "World's Fair" by the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE).[1]

| 1982 Knoxville | |

|---|---|

The 1982 World's Fair logo | |

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Specialized exposition |

| Category | International specialized exposition |

| Name |

|

| Motto | Energy Turns the World |

| Building(s) | Sunsphere, Tennessee Amphitheater |

| Area | 28 hectares (69 acres) |

| Invention(s) | |

| Visitors | 11,127,786 |

| Organized by |

|

| Participant(s) | |

| Countries | 22 |

| Business | More than 50 |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| City | Knoxville |

| Venue | World's Fair Park |

| Coordinates | 35.962°N 83.924°W |

| Timeline | |

| Bidding | 1975 |

| Awarded | 1980 |

| Opening | May 1, 1982 |

| Closure | October 31, 1982 |

| Specialized expositions | |

| Previous | Expo 81 in Plovdiv |

| Next | 1984 Louisiana World Exposition in New Orleans |

| Universal expositions | |

| Previous | Expo '70 in Osaka |

| Next | Seville Expo '92 in Seville |

| Horticultural expositions | |

| Previous | Floralies Internationales de Montréal in Montreal |

| Next | Internationale Gartenbauaustellung 83 in Munich |

| Simultaneous | |

| Horticultural (AIPH) | Floriade 1982 |

The KIEE opened on May 1, 1982, and closed on October 31, 1982, after receiving over 11 million visitors. Participating nations included Australia, Belgium, Canada, The People's Republic of China, Denmark, Egypt, France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, Panama, Peru, the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, the United Kingdom, the United States, and West Germany. It was the second World's Fair to be held in the state of Tennessee, with the first being the Tennessee Centennial Exposition of 1897, held in the state's capital, Nashville.[2]

The fair was constructed on a 70-acre (280,000 m2) site between Downtown Knoxville and the University of Tennessee campus. The core of the site primarily consisted of a deteriorating Louisville and Nashville Railroad yard and depot. The railroad yard was demolished, with the exception of a single rail line, and the depot was renovated for use as a restaurant during the fair. The Sunsphere, a 266-foot (81 m) steel tower topped with a five-story gold globe, was built as the main structure and symbol for the exposition. Today, the Sunsphere stands as a symbol for the city of Knoxville.

Background and construction

The first World's Fair to be held in Tennessee occurred in the state's capital, Nashville, in 1897.[2] Knoxville developers cultivated the idea for a World's Fair in their city after several visited Spokane, Washington, which hosted a World's Fair in 1974. In November 1974, W. Stewart Evans, president of the Downtown Knoxville Association, proposed the idea of the fair to the city government and a group of Knoxville business owners after visiting the exposition in 1974.[3] Evans cited Knoxville's association with energy research and development, spurred by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), and the University of Tennessee. This made Knoxville a potential energy center and suggested the promotion of a energy-themed World's Fair as early as 1980. Officials cited the city's location along Interstate 40 and position in the most populated one-third of the United States as crucial advantages.[4] Knoxville had also previously held an Appalachian-oriented regional exposition promoting the environmental movement in the United States in 1913.[5]

Knoxville mayor Kyle Testerman appointed local banker Jake Butcher to lead an exploratory KIEE committee. Butcher served as one of the main driving forces behind the fair. Within the city, Knoxvillians referred to the fair as "Jake's Fair".[3] An administrative body known as the Knoxville Foundation Inc. was established to organize and operate the event.[6] There was skepticism, both locally and nationally, about the ability of Knoxville, described as a "scruffy little city" by The Wall Street Journal in a 1980 news article, to successfully host a World's Fair.[7] This controversy contributed to the development of the term “Scruffy City,” as a nickname synonymous with Knoxville.[8]

Major politicians representing Tennessee across the aisle and financial boosters supported the idea and prompted interest from the Ford Administration. Then-Secretary of Commerce Elliot Richardson, while inquired, discouraged the idea for Knoxville to host an exposition in 1980, citing a conflict from Los Angeles who planned to host a fair the same year. Richardson would approve for an exposition in Knoxville for the year 1982.[4] Jake Butcher, facing criticism for his efforts for the KIEE, offered a rebuke in a 1981 interview with United Press International, "They called the fair the Jimmy Carter-Jake Butcher pork barrel, but they never revealed that [U.S. Senator] Howard Baker also supports it. I don't expect to get anything personally out of the World's Fair." Intent on running for governor in Tennessee in 1982, Butcher pointed out that his opponent, then-Governor Lamar Alexander, was also an outspoken supporter of the fair.[9]

Public opinion of Knoxvillians leading up to the fair changed drastically, with a 1979 poll showing a majority of residents disapproved of the fair but later polls showing massive approval.[9]

The fair would prompt investment into minority-owned businesses. Civil rights activist Avon Rollins, who served as an executive for the TVA, would ask for a significant portion of the fair proceeds go to Knoxville's African-American community. The fair's iconic red flame-logo apparel was contracted to be produced by Upfront America, a black-owned business. Upfront America would go on to sell more than 500,000 expo shirts.[4] Leading up to the fair, the KIEE committee faced competition in recruiting larger corporate sponsors due to the development of EPCOT Center at the Walt Disney World resort, a permanent scientific-focused amusement park.[9]

Most of the KIEE's financial support came from the United States federal government which provided an estimated $44 million in funding. The Tennessee state government provided $3 million, and the Knoxville municipal government approved a nearly $12 million bond. Jake Butcher, through his companies, gave approximately $25 million.[9] An additional $224 million in federal and state funding was utilized by the Tennessee Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration to improve the transportation infrastructure system surrounding Knoxville in preparation for the fair. These improvements included completion of the Interstate 640 semi-beltway and improvements to the infamous "Malfunction Junction" of then I-75 (now I-275) and I-40 north of the fair site.[9]

Located along the Second Creek watershed between downtown Knoxville and the University of Tennessee campus, the roughly 70-acre disused Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N) railyard was selected as the site for development of the exposition.[4] The railyard would be demolished to make way for the nation-representing pavilions and exhibits, the Tennessee Amphitheater, and the Sunsphere. The L&N station, however, would be redeveloped into a restaurant and office space.[4] Acreage located south of the railyard site near the University of Tennessee campus would be home to the exposition's midway, which included the Great Wheel, the tallest Ferris wheel in the world at the time.[4] A gondola system was developed to provide rapid connections to the exhibit and midway areas of the fairgrounds.[4] For the design of the Sunsphere, the KIEE recruited Knoxville-based architectural firm Community Techtonics, which was known in the region for its design of the Clingmans Dome Observation Tower in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the "SkyMart" elevated-sidewalk system in downtown Morristown, nearly 50 miles east of Knoxville.[11] Construction would break ground in 1980.[12]

Regarding recruitment for country sponsors, the KIEE received confirmation for participation from western European countries including the United Kingdom, France, West Germany, Italy, and the 10-nation European Economic Community, along with Australia, Mexico, Japan, and the People's Republic of China. China's participation proved historic given the country's shift to a more capitalist economy; the KIEE would be the first exposition involving China since 1904.[13] The KIEE invited the Soviet Union for participation and a swimming competition against the United States, but the invitation for a participating was rescinded following the Soviet Union's military invasion of Afghanistan in 1979.[13] In total, 25 nations were signed to participate at the 1982 World's Fair by its opening.[13] However, only 22 of those signed took part by opening day of the KIEE.[14]

Fair operations

Opening day

On May 1, 1982, the 1982 World's Fair opened to a crowd of 87,000 with the theme "Energy Turns the World". Television commercials broadcast prior to the fair used the marketing tagline "You've Got To Be There!"[15] The opening ceremony was broadcast on local and regional television stations, with President Ronald Reagan arriving to open the fair.[3] Television personality and Winchester native Dinah Shore was the master of ceremonies for the fair.[16] A six-month pass to the fair sold for $100[17] ($303.00 in 2022 dollars[18]).[19][15]

Fair participation and exhibits

From its commencement on May 1, to its closing on October 31, the fair attracted 11,127,780[20] visitors from all over the United States and the world, making among the best attended World's Fair in U.S. history among those sanctioned by the BIE. It had the highest attendance among the four Specialized Expos held in the United States. It made a profit of $57, far short of the $5 million surplus projected by organizers and boosters.[6] The city of Knoxville was left with a $46 million debt. This debt would be paid in full in May 2007.[6]

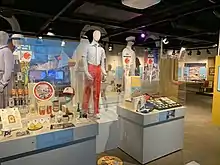

In total, 22 nations, 7 states, and more than 50 corporations presented exhibitions at the fair revolving around energy, innovation, technology, and sustainability.[14] Participating nations included Australia, Belgium, Canada, The People's Republic of China, Denmark, Egypt, France, Greece, People's Republic of Hungary, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, Panama, Peru, the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, the United Kingdom, the United States, and West Germany.[21] Panama, a late-comer to the fair, never occupied its pavilion space, which was eventually unofficially occupied by a group of Caribbean island nations.[22][23] Communication problems between Panama and fair officials delayed occupancy,[24] then it was announced that the country would not show due to "economic problems".[25]

The Peruvian exhibit featured a mummy that was unwrapped and studied at the fair. The Egyptian exhibit featured ancient artifacts valued at over US$30 million.[26] Hungary, the home country of the Rubik's Cube, sent the world's largest Rubik's Cube with rotating squares for the entrance display to its pavilion. The Rubik's Cube remains in World's Fair Park, where it is on display at the Knoxville Convention Center.[27][28] Every night of the fair, at 10 pm, a 10-minute fireworks display was presented that could be seen over much of Knoxville.[4]

Entertainment

Performances by famous artists, actors, and musicians occurred at the Tennessee Amphitheater and across other areas of the fairgrounds and Knoxville, including Bob Hope, Tennessee Ernie Ford, Johnny Cash, Chet Atkins, Hal Holbrook, Glen Campbell, and Ricky Skaggs.[14]

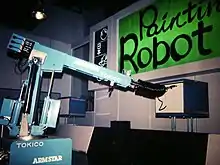

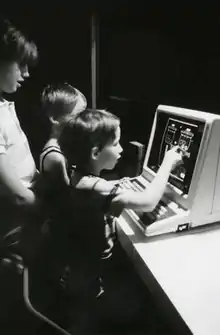

Innovations showcased

The 1982 World's Fair brought the debut of several inventions and concepts, primarily focused on energy, technology, and sustainability.

Oak Ridge National Laboratory physicist George Samuel Hurst had showcased his patented resistive touchscreen technology that was developed in 1975 as result of a partnership with his company Elographics and German conglomerate Siemens. Visitors were able to use computers with the touch-screen technology.[29] Tetra Pak showcased its boxed shelf-stable milk.[30] Coca-Cola organized a measure of several flavored mixtures of its traditional Coke soda during the exposition. Visitors would test lime, lemon, vanilla, and cherry flavors. By the end of the KIEE, Coca-Cola found that the cherry-flavored soda was the most popular. As a result, Coca-Cola Cherry would be distributed in 1985 as a result of its successful introduction at the 1982 World's Fair.[31] Oil corporation Texaco showcased the concept of pay at the pump, as part of the advances in energy.[32] An early rendition of the cordless telephone was introduced to the public at the KIEE.[33] The Ford Motor Company showcased a Lincoln Town Car with a built-in car phone and a concept car known as the AFV, which relied on alternative fuel consumption.[34] One-hour photographic processing was introduced by Kodak and used by visitors of the exposition.[34]

Geodesic dome housing exhibits were showcased to promote sustainable development to confront the then-ongoing energy crisis.[34] Housing powered entirely by solar power was constructed by the United American Solar Group to promote solar energy.[34] The TVA would support an exhibit promoting energy conservation and private greenhouse usage.[34]

Knoxville-based fast-food chain, Petro's Chili & Chips made their debut at the fair. Today, the chain consists of several locations in the state with most primarily located in East Tennessee.[35]

Events

The Pittsburgh Steelers and the New England Patriots played a preseason football game at Neyland Stadium on August 14, 1982.[36] The Steelers won the game 24–20 to a crowd of 93,251, making it the fourth-best-attended NFL game in history.[4][37]

The University of Tennessee would utilize its residence halls and dormitories for housing nearly 60,000 visitors during the exposition's six-month tenure.[38]

An NBA exhibition game took place between the Boston Celtics and Philadelphia 76ers at Stokely Athletic Center on October 23, 1982.[39]

Difficulties

Hotels and other accommodations in Knoxville were not permitted to take reservations directly. Room reservations for everything from hotels to houseboats were sold in a package with fair admission tickets through the first eleven days and were handled by a central bureau, Knoxvisit. Its financial and administrative troubles resulted in reservations being taken over by Property Leasing & Management, Inc. (PLM).[40][41] It also struggled with the operation and filed for bankruptcy.[42][40]

Jake Butcher's financial services corporation, United American Bank (UAB), failed shortly after the exposition in 1983. UAB had been raided by federal banking regulators the day after the fair's closure.[43] On February 14, 1983, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation seized control of the bank due to irregularities in its financial records. This action caused public speculation that the bank's failure was due in part to Butcher's financing of the World's Fair.[44]

Legacy

Given the success of the fair, Knoxville residents speculated that the fair would put the city on track to become a major hub city in the Southeastern United States such as Atlanta or Charlotte.[45] However, growth in Knoxville was relatively low compared to that of Chattanooga, which received national attention for its riverfront redevelopment projects.[45]

The U.S. Pavilion would operate as a soccer arena, but in 1991, the city of Knoxville demolished the U.S. Pavilion in a controlled demolition. It had developed structural problems that could not be safely resolved after years of neglect. The site of the pavilion was cleared and developed for a parking lot along Cumberland Avenue, adjacent to the site of the Knoxville Convention Center in World's Fair Park.[32]

The site of the Korean and Saudi Arabian pavilions and the Tennessee Gas Industries exhibit was redeveloped into a performance lawn and hosted the Hot Summer Nights rock music festival from 1991 to 1999, when the Knoxville municipal government indefinitely suspended concerts on the lawn. Ashley Capps, a Knoxville entertainment coordinator, cited the suspension of Hot Summer Nights at World's Fair Park as the start of the iconic Bonnaroo Music Festival.[46]

The site of the Japanese Pavilion became the new location for the Knoxville Museum of Art in 1990.[32] The Elm Tree Theater located adjacent to the former pavilion was added as part of the Knoxville Museum of Art's courtyard. The elm tree was later struck by lightning and was cut down. The courtyard of the theater has since remained empty. Many of the pavilion sites and the fair's midway located south of the main park were given to the University of Tennessee for future campus extensions and student parking.[32]

By 1996, World's Fair Park was subject to 14 plans to redevelop the site, all of which were unsuccessful.[47] In the same year, Knoxville and the 1982 World's Fair were featured prominently in an episode of The Simpsons, "Bart on the Road". In the episode, Bart, having obtained a fake ID, travels to Knoxville with his friends to visit the fair after seeing an advertisement in a tourism brochure, only to learn that it closed a decade before. Nelson frustratedly throws a stone at the Sunsphere, causing it to collapse on the group's rental car, stranding them in Knoxville.[48] Knoxville municipal personnel would criticize the show's portrayal of the city and World's Fair Park, as at the time, the Sunsphere and the main facilities at the park were in good condition and received regular maintenance.[47] The last known attempt of redeveloping the fair site came in late 1996, as a mixed-use development named after the Tivoli gardens in Copenhagen.[47]

In 2000, the park was closed for two years for the construction of the Knoxville Convention Center in the space formerly occupied by Rich's/Millers Garage, the site of the KUB Substation exhibit, and the site of America's Electric Energy Exhibit.[32]

The Tennessee Amphitheater, the only structure other than the Sunsphere that currently remains from the World's Fair, was condemned to demolition in 2002.[49] Popular sentiment from Knoxville residents and officials supported restoring it, and the theater was renovated between 2005 and 2007, reopening in 2007.[50] In 2007, the amphitheater was voted one of the top fifteen architectural works of East Tennessee by the East Tennessee chapter of the American Institute of Architects.[51]

In the summer of 2002, the World's Fair Park was reopened to general events and concerts, such as Earth Fest and Greek Fest. An Independence Day celebration is held on the park lawns every year, with the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra playing a free concert with a massive fireworks display. In May 2007, the East Tennessee Historical Society (ETHS) opened a temporary exhibit in its museum located in Downtown Knoxville, commemorating the 25th anniversary of the World's Fair. On July 4, 2007, one of the annual celebrations was held in conjunction with festivities commemorating the 25th anniversary of the 1982 World's Fair. The following day, July 5, 2007, the Sunsphere's observation deck reopened to the public after renovations.[52] In 2020, rock band The Dirty Guv'nahs curated the Southern Skies Music Festival at the performance lawn of World's Fair Park. Postponed from its original start in May 2020 by the COVID-19 pandemic, the festival debuted on May 14, 2022.[53]

In 2022, the ETHS and the University of Tennessee's Hodges Library would open temporary exhibits regarding the KIEE commemorating its 40th anniversary.[54][38] A celebration of the 40th anniversary of the KIEE was held during the weekend of May 20–22, 2022, including a full-day festival organized by Knoxville's convention and visitors bureau.[55] Local media covered the event and provided prior coverage of the original event.[56][57]

Collectibles

Many collectible items were made specifically for the World's Fair, ranging from cups, trays, plates, belt buckles, and several other objects. Some of the more notable items include:

- With the focus of the World's Fair on technology and energy, video games of the era were also featured at the Fair. In the arcade area, attendees could find seven video arcade game tokens that had been minted for the Fair, each depicting a different and popular game of the time. The seven games on each of the tokens are Pac-Man, Ms. Pac-Man, Space Invaders, Qix, Gorf, Scramble, and Donkey Kong.[58]

- World's Fair Beer was also released at the beginning of the fair. 250,000 cases of the beer was sold during the fair's duration, totaling nearly six million cans sold over the six months. Rick Kuhlman, who was a marketing director for a beer wholesaler at the time, had come up with the idea for the beer. He had to pre-sell 10,000 cases of the beer to pay for the initial batch. The beer would go on to be released in nine different colored cans, beginning with red, then blue, and eventually, green, brown, gold, black, purple, yellow, and orange. Each color represented its own production batch and when a color was sold out, that color was finished. The beer was often purchased and never drunk, as many fair-goers speculated that the beer cans would one day be a rare collectible.[59] To observe the 35th anniversary of the fair, World's Fair Beer was brought back into production in May 2017 for a limited time at several Knoxville breweries and pubs.[60]

Gallery

Australian Pavilion

Australian Pavilion Baptist Pavilion and Waters of the World

Baptist Pavilion and Waters of the World Sunsphere

Sunsphere Tennessee River, Australian and Canadian Pavilions and Midway

Tennessee River, Australian and Canadian Pavilions and Midway U.S. Pavilion

U.S. Pavilion Tennessee Amphitheater

Tennessee Amphitheater KUB Substation Exhibit and U.S. Pavilion

KUB Substation Exhibit and U.S. Pavilion

References

Bibliography

- World Class Politics: Knoxville's 1982 World's Fair, Redevelopment and the Political Process Joe Dodd.[2]

- Knoxville's 1982 World's Fair Martha R. Woodward.[37]

- 1982 World's Fair Official Guidebook Knoxville International Energy Exposition, Inc.[61]

- 1982 World's Fair Transportation System Evaluation U.S. Department of Transportation.[62]

- Exhibiting the Future: The 1982 World's Fair and Walt Disney World's EPCOT Center Cristin J. Grant.[1]

- The Expo Book Gordon Linden.[63]

- Federal Supervision and Failure of United American Bank U.S. Government Printing Office.[64]

- (Re)imagining an urban identity: Knoxville and its 1982 International Energy Exposition Jennifer Bradley.[65]

Sources

- Grant, Cristin (2002). Exhibiting the Future: The 1982 World's Fair and Walt Disney World's EPCOT Center. State University of New York College at Oneonta. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- Dodd, Joe (1988). World Class Politics: Knoxville's 1982 World's Fair, Redevelopment and the Political Process. Sheffield Publishing Company. ISBN 9780881333565. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- Wheeler, Bruce (2002). "Knoxville World's Fair of 1982". Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Archived from the original on April 27, 2012.

- Neely, Jack (April 2022). "1982 World's Fair in Hindsight". Knoxville History Project. Archived from the original on May 22, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- Neely, Jack (November 11, 2009). "A Fair to Remember: Knoxville's National Conservation Exposition of 1913". Metro Pulse. Archived from the original on July 11, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- "1982 World's Fair shows $57 profit". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Associated Press. February 3, 1985. p. 11-F. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved June 18, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Granju, Katie Allison (September 1, 2006). "The "Scruffy Little City" pulls off a real World's Fair". WBIR-TV. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- McElroy, Jack (October 7, 2018). "Does Knoxville still want to be called 'scruffy,' or is that bad for the brand?". Knox News Sentinel. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- Daniel, Leon (June 4, 1981). "'What If You Gave A World's Fair And Nobody Came?'". UPI. Archived from the original on April 22, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- "U.S. Agencies Weigh Use of Pavilion, Official Says". The Knoxville News-Sentinel. October 22, 1981. p. 2. Retrieved October 23, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Sunsphere". Society of Architectural Historians. July 17, 2018. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- North, John (April 29, 2022). "'Such a good time': WBIR alumni recall audacious, hectic, rewarding launch of 1982 World's Fair in Knoxville". WBIR-TV. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- Tucker, Melanie (March 21, 2022). "'You Should've Been There!': 1982 World's Fair exhibit will take you back in time". The Maryville Daily Times. Archived from the original on April 12, 2022. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- Schulman, Bruce. "The 1982 World's Fair: Exhibits". 1982 World's Fair Research Site. Archived from the original on April 30, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- East Tennessee Historical Society (2002). "20th Anniversary of the 1982 World's Fair". Archived from the original on February 6, 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- Powelson, Richard (May 2, 1982). "Reagan Opens Fair With Plea for Peace". The Knoxville News-Sentinel. Knoxville, Tennessee. p. A-1. Retrieved June 18, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "History Behind World's Fair Park 1982 | Legacy | Fun Facts". www.worldsfairpark.org. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- "$100 in 1982 → 2021". Inflation Calculator. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- "1982 Knoxville". www.bie-paris.org. Archived from the original on August 10, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- "The Fair Participants". Harlan Daily Enterprise. April 23, 1982. pp. 6B. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- "1982 Worlds Fair in Hindsight". Knoxville History Project. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- Siler, Charles (July 8, 1982). "Caribbean Islands To Sponsor Fair Exhibit". The Knoxville News-Sentinel. Knoxville, Tennessee. p. A-1. Retrieved June 27, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Siler, Charles (April 17, 1982). "Two Weeks Before Opening Day, Panamanian Pavilion Still Empty". The Knoxville News-Sentinel. Knoxville, Tennessee. p. 10. Retrieved June 27, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Panama Won't Have Exhibit". The Knoxville News-Sentinel. Knoxville, Tennessee. April 28, 1982. p. A-1. Retrieved June 27, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Siler, Charles (May 2, 1982). "Recruiting: Most Visitors Are Home folk; Wonders Came From Afar". The Knoxville News-Sentinel. Knoxville, Tennessee. p. I-7. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved June 18, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Brown, Fred (July 2, 2007). "Rubik's Cube: Coming 'round again; World's Fair icon's future not yet squared away". Knoxville News Sentinel. Archived from the original on May 23, 2010. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

- "Knoxville, Tennessee – World's Largest Rubik's Cube". RoadsideAmerica. Archived from the original on May 23, 2009. Retrieved August 9, 2009.

- Olito, Frank (July 18, 2019). "15 inventions and landmarks that you had no idea debuted at World's Fairs". Insider. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- "Remembering the 1982 World's Fair in pictures". Knoxville News Sentinel. November 12, 2021. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- Staff (March 4, 1985). "Business Notes Soft Drinks". Time. Archived from the original on April 8, 2008. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- Burk, Tonja (March 30, 2012). "Remembering the 1982 World's Fair". WBIR-TV. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- Trieu, Cat (November 16, 2017). "Remembering the 1982 World's Fair". Daily Beacon. University of Tennessee. Archived from the original on January 13, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- Williams, Bill (May 1, 2007). "WBIR 1982 World's Fair 25th Anniversary Special" (YouTube Video). WBIR-TV. Archived from the original on May 9, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- "Petro's Official Site "About Us" page". Archived from the original on May 27, 2019. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- "Pats To Play Steelers at Knoxville 'Fair"". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. November 28, 1981. Archived from the original on April 24, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- Woodward, Martha (2009). Knoxville's 1982 World's Fair. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738568355. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- Rudolph, Martha. "Exhibit: The 1982 World's Fair 40th Anniversary Celebration". University of Tennessee. Archived from the original on March 13, 2022. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- Thurman, Sybil (July 1982). "The World's Fair: 1982 - A Special Report". Aramco World. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- "Lodging Firm At Fair Reports Few Claims". The Commercial Appeal. Memphis, Tennessee. October 14, 1982. p. C7. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved June 16, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Tennessee Sues World's Fair For 3,500 Tourists' Refunds". The New York Times. UPI. December 12, 1982. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 19, 2019. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- Murray, Sonia (October 15, 1991). "Olympic-Size Task: Committee faces challenge in managing hotel bookings". The Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia. p. C1, C8. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved June 18, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hagerty, James (July 28, 2017). "Jake Butcher's Triumph With 1982 World's Fair Swiftly Turned Sour". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on April 22, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- "Carnival and collapse: 1980s brought World's Fair and Butcher bank failure". Knoxville News Sentinel. September 30, 2012. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- Shearer, John (April 28, 2007). "Remembering The Knoxville World's Fair". Chattanoogan. Archived from the original on October 8, 2020. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- Wilusz, Ryan (April 28, 2021). "Bonnaroo, America's favorite music festival, was born of canceled plans and construction". Knoxville News Sentinel. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- Jacobson, Lou (April 19, 1997). "Knoxville Hopes To Have Last Laugh In Struggle to Develop World's Fair Site". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- Groening, Matt (1997). Richmond, Ray; Coffman, Antonia (eds.). The Simpsons: A Complete Guide to Our Favorite Family (1st ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-06-095252-5. LCCN 98141857. OCLC 37796735. OL 433519M.

- Doug Mason (September 18, 2005). "Professor sings praises of iconic World's Fair structure". The Knoxville News Sentinel. Archived from the original on August 19, 2016.

- "World's Fair Park Amphitheater". World's Fair Park. Archived from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- Doug Mason (December 16, 2007). "Area architects' picks for ET's Top 15 structures may surprise you". The Knoxville News Sentinel. Archived from the original on August 19, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- Whitehead, Paul N. (July 6, 2007). "World's Fair Park main attraction reopened to the public Thursday". Knoxville News Sentinel. Archived from the original on July 8, 2007. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- "Southern Skies Music Festival". Southern Skies Music Festival. Archived from the original on April 22, 2022. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ""You Should've Been There!" The 40th Anniversary of the 1982 World's Fair". East Tennessee Historical Society. December 2, 2021. Archived from the original on April 18, 2022. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- "The 1982 World's Fair 40th Anniversary Celebration". Visit Knoxville. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved April 30, 2022.

- "1982 World's Fair 40th Anniversary Celebration in pictures". www.knoxnews.com. Archived from the original on May 27, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- Riley, Sarah (May 19, 2022). "40th anniversary party for the 1982 World's Fair is Saturday - what to know plus a look back". Knoxville News Sentinel. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- "Video Game Arcade Token Gallery". digthatbox.com. October 9, 2014. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- Rupp, Allison (May 1, 2012). "Thirty years later, Knoxvillians celebrate 1982 energy expo". Knoxville News Sentinel. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- Whetstone, Tyler (May 1, 2017). "Relaunch: World's Fair Beer on sale again". Knoxville News Sentinel. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- The 1982 World's Fair: Official Guidebook. Exposition Publishers. 1982. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- 1982 World's Fair Transportation System Evaluation. United States Department of Transportation. December 1982. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- Linden, Gordon (April 2014). The Expo Book. JRVD Architects. ISBN 9780557644162. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- Federal Supervision and Failure of United American Bank (Knoxville, Tenn.). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1983. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- Bradley, Jennifer (December 2003). "(Re)imagining an urban identity : Knoxville and its 1982 International Energy Exposition". Masters Theses. University of Tennessee Press. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

External links

- 1982 World's Fair Research Site, by Bruce Schulman

- Official website of the BIE

- European Patent Office

- 1982 World's Fair 25th Anniversary site (archived)

- ExpoMuseum's 1982 World's Fair Section Archived February 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine